German Embassy (Saint Petersburg)

The former “Imperial German Embassy in Saint Petersburg ” is a building complex designed by Peter Behrens for the purposes of the Deutscher Werkbund and moved into in 1912 on Isaaksplatz in what was then the capital of the Russian Empire.

Building history

The head of the Foreign Office, Alfred von Kiderlen-Waechter , had, at the suggestion of Edmund Schüler, invited the Art Nouveau artist Peter Behrens to submit a draft. Within eight weeks he submitted his plans, which Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and the Kaiser approved in autumn 1911. The location was the corner property between Morskája Street and Isaac's Square, which had previously been the one-story old embassy building acquired in 1873 (built from 1815, rebuilt in 1871). The building, including the interior furnishings, was completed in 18 months and was ready to move into in January 1913. As planned, the construction costs amounted to 1.7 million marks . It is not documented whether and to what extent the later famous architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe , who had accompanied the shell construction as a young site manager but then left the Behrens office, had a creative role in the planning.

shape

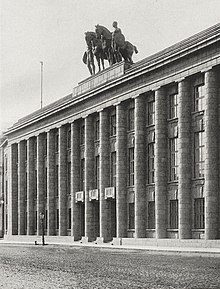

The two three-storey main wings contained the representative rooms, offices and the ambassador's apartment, two further lower wings, also shaped into an “L”, close off the inner courtyard of the building block to the west. The asymmetrical main facade is oriented towards the square; its entire width of 58 m is dominated by a huge row of half-columns, which divide the 15 axes of the main view in a colossal order extending over all floors and continue laterally in a correspondingly dimensioned row of pilaster strips . The entrance zone is marked by three balconies barely protruding over the escape and above all by a (now destroyed) monumental group of sculptures (see below) above the cornice. The surface of the red-gray Finnish granite is roughened to varying degrees, so the facade facing the shaded north side makes a somewhat gloomy impression today. But the design of all the details is strict and clear: the columns lack flutes and bases, the plinth-like capitals are only hinted at. The structure also dispenses with plinths, open staircases, oversized portals or bulky entablature zones, otherwise indispensable elements of lordly architecture .

If the exterior nevertheless expresses a certain monumentality, the partially preserved interior design turns completely away from conservative ideas of style and the dynastic pomp, which until then was regarded as indispensable for imperial embassies. Bright colors, abundant electrical light sources, generous, strictly framed wall panels and restrained decor gave (and in some cases still give) the rooms a radical modernity.

Architectural-historical and urban planning classification

The building stands in a variety of architectural and historical contexts. On the one hand, he tries to fit into the urban environment of the urban landscape, which is characterized by numerous classicist palace facades. Behrens achieved this by adopting typical Petersburg motifs: the dense row of columns, the vertical internal structure with a clear emphasis on the horizontal in the entablature zone and a renunciation of dynamic movement in the facade surface. The eaves height corresponds to that of the neighboring buildings, the facade blends in harmoniously with the ensemble of the perimeter development of Isaakplatz. On the other hand, the message should set an example of German and at the same time modern architecture. The relationship to Prussian architecture has been seen, for example, in similarities with the Brandenburg Gate and the Altes Museum . What was new, especially for an embassy building that had previously been committed to monarchical representation, was the renunciation of all excessive formulas. In the German work federation , the Behrens had co-founded, this stylistic ideal was developed. With his material-appropriate, functionalist design language, the architect strove to "replace the traditional and international ritual of monarchical self-glorification, the narrowing of a German embassy to the dynastic glorification of the Hohenzollern, with a representation of the scientific-technical, industrial-commercial and artistic performance of the modern, pronounced middle-class middle class Germany. “(Buddensieg).

Architectural criticism in the controversy

The classification of the architectural quality and ideological evaluation comes to very contradicting judgments. Russian and French architects found the building to be very "Teutonic". Even the people of Petersburg took part in the lively discussion, which was to escalate into vandalist attacks in 1914, predominantly in an anti-modernist sense. Kaiser Wilhelm II , who would have preferred a neo-baroque palace, expressed disparagingly about the completed building, as did Tsar Nicholas II. Russian architects, on the other hand, recognized its qualities. Based on Behrens' model, several facades with a similar colossal order emerged during the Soviet period in Leningrad, for example the House of the Soviets (1936–1941), but the consistent way of simplifying and reducing the forms was here in favor of a decorative enrichment in the sense of the Stalinist Art doctrine withdrawn. Hitler later also admired the “excellent building”. This appreciation during the Nazi era gave the embassy building an ideological precursor to the regime's representative buildings, such as the Haus der Kunst by Paul Ludwig Troost or the New Reich Chancellery by Albert Speer . In contrast, differentiating analyzes have emphasized how much - with all the striving for representation - the reduction of the form and a stylization in the spirit of the classic in this building is determined by a “subtle modernity” and a “dialogue between tradition and innovation”. This precludes locating the Behrens embassy building on a line of continuity between Wilhelmine and Fascist “intimidation architecture”.

Encke's sculptures

The group of sculptures on the attic , the embassy’s only sculptural decoration, was donated by the German colony in St. Petersburg and was destroyed in 1914 (see below). The monumental bronze group of sculptures by the Berlin sculptor Eberhard Encke accentuated the central axis with the portal zone above the main cornice, which is only slightly raised. Two athletic naked men lead a pair of horses. They are placed symmetrically to each other, powerful, but standing still, without any drama or heroic pose. A proto-fascist meaning can hardly be assumed for the pictorial work. It is obvious, however, to interpret the group as an allegory of the Russian and German empires with their kinsmanlike state leaders. The motif of the Rosselenker, already created in Greek antiquity by the fraternal Dioscuri couple, had also been thematized repeatedly in Petersburg, for example as a literal copy of antiquity in front of the temple front of the "Manege" two blocks further to the right. The Rosselenker on the Anitschkow Bridge are much more animated and pathetic .

Later story

A few days after the start of the war, on August 4, 1914, the building suffered severe damage during the strikes and unrest in St. Petersburg, vandalizing groups stormed the embassy and overthrew the Dioscuri group from the roof. After the First World War, from 1922 to 1938 and again in 1940, a German consulate resided here again. During the siege of Leningrad it was used as a hospital. In the 1980s it was the seat of the Intourist travel agency. From 2001 the building was restored, from which essential parts of the immobile interior have been preserved. Today the building houses departments of the Justice Department and the district administration.

The restoration of a replica of the Rosselenker is planned; a plaster model in original size is already in the entrance hall.

literature

- Karl Schaefer : Kaiserl. German Embassy in St. Petersburg . in: German Art and Decoration , 32, 1913. pp. 261–292 (with numerous illustrations of the interiors) digitized

- Tilmann Buddensieg : The imperial German embassy in Petersburg . In: Martin Warnke (ed.): Political architecture in Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Cologne 1984, pp. 374-398.

- Alan Windsor: Peter Behrens. Architect and designer . Stuttgart: DVA, 1985, pp. 123-127.

- Georg Krawietz: Peter Behrens in the Third Reich , Weimar 1995, pp. 75–81.

- Платонов П. В. Здание Германского посольства // Памятники истории и культуры Санкт-Петербурга: Исслед. и материалы. СПб., 2002. Вып. 6. С. 228-237.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Windsor, p. 123, Buddensieg, p. 384 with note 23.

- ↑ Schäfer, p. 261

- ↑ Schäfer, p. 262 and a note on the previous buildings in the Saint Petersburg encyclopaedia (engl.)

- ↑ See the illustrations from Schäfer

- ↑ Windsor, p. 125. - Buddensieg, p. 393 f., Nevertheless wants to recognize Miesen's hand in the execution details.

- ^ Windsor, p. 125

- ↑ Krawietz, pp. 75–76, gives a detailed account of the various statements in a research report.

- ↑ Buddensieg, p. 379

- ↑ More examples in Buddensieg, pp. 377–380.

- ↑ For example: Hans-Joachim Art : Architecture and Power. Reflections on Nazi architecture. In: Comments. Reports from the Philipps University of Marburg, May 3, 1971, p. 51.

- ↑ Buddensieg, pp. 390–395. - Krawietz, p. 76

- ↑ Schäfer, p. 274

- ↑ Krawietz, pp. 78–79

- ↑ According to Saint Petersburg encyclopaedia : " In July 1914, after Germany declared war on Russia " (sic!). Buddensieg specified, p. 382

- ↑ Buddensieg, p. 374.

- ↑ Fontanka (Russian) of July 2, 2008

- ↑ Observation in March 2016

Web links

Coordinates: 59 ° 55 ′ 56.9 " N , 30 ° 18 ′ 23.7" E