The girlfriend (magazine)

| The girlfriend | |

|---|---|

|

|

| description | lesbian magazine |

| language | German |

| publishing company | Friedrich Radszuweit Verlag (Germany) |

| First edition | August 8, 1924 |

| attitude | March 8, 1933 (prohibited) |

| Frequency of publication | monthly (1924–1925), fortnightly (1925–?), weekly (? –1933) |

| Sold edition | unknown number of copies |

| editor | Friedrich Radszuweit |

| ZDB | 545589-3 |

The girlfriend (subtitle The ideal friendship sheet ) was a magazine of the Weimar Republic . It was published in Berlin from 1924 to 1933 and is considered the first lesbian magazine.

It was published as an “official publication organ” by the Bund für Menschenrecht , one of the leading associations for the interests of homosexuals at the time, and, like other lesbian magazines of the era, was closely intertwined with the local lesbian culture in Berlin. Women’s groups and activists associated with Die Freund and the Bund für Menschenrechte organized readings, events and discussion forums in Berlin, and Die Freund made a significant contribution to networking . She took a clear political stance, provided information on the subject of lesbian life, published short stories and novels as well as advertisements for lesbian meeting places or private personals.

Release dates

The girlfriend appeared in Berlin from 1924 to 1933 , published by the Bund für Menschenrecht . It was a joint organ of the Federation for Human Rights and the "Federation for Ideal Women's Friendship". It was initially located in 1925 at Kaiser-Friedrich-Strasse 1 in Berlin-Pankow, and by 1927 it had an office at Neue Jakobstrasse 9 in Berlin-Mitte, which, according to information, was manned from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. from 1932.

The friend was available in all of Germany and Austria by subscription , at least in Berlin also from street vendors and magazine sellers, at a price of 30 pfennigs in 1924/1925, then for 20 pfennigs. Some editions make the seriousness recognizable by printing on the title page such as "This magazine can be displayed publicly everywhere!". In addition to the sales revenue and those from the advertising business, the editorial team also asked members and subscribers for donations.

The exact circulation size of The Girlfriend is unknown, it is assumed that it was the most widely distributed lesbian magazine of the Weimar Republic and that its circulation was well above that of any other lesbian magazine in the German-speaking area until the 1980s. Following this assumption, its circulation must have been well over 10,000 copies, since this was the circulation size of the competing Frauenliebe in 1930.

Edition history

After the first two editions of The Girlfriend of August 8, 1924 and September 12, 1924 had appeared as a supplement in the Blätter für Menschenrechte , subsequent editions appeared as separate booklets with a page length of 8 to 12 pages. The girlfriend was the “first new independent magazine of the Radszuweit publishing house”. In 1925 it was announced that from April 1, Die Freund would appear with even larger pages (up to 20 pages) and a higher price of 50 pfennigs, but the attempt failed and the old format remained. The first issue already contained a supplement Der Transvestit , which was featured repeatedly, albeit irregularly, in The Friend . Until 1926, the newspaper of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee around Magnus Hirschfeld was also included as an insert in The Girlfriend .

The pace of publication changed: in the first year it was still a monthly magazine, from 1925 it appeared every two weeks and later even weekly. The 1928 editions appeared on Mondays, according to the title pages it appeared on Wednesday in 1932.

In 1926 there was no separate edition of The Friend , instead it appeared as a supplement to the friendship sheet . The reasons for this interruption are unknown. Between June 1928 and July 1929, Die Freund had to interrupt its appearance again. It was affected by the law for the protection of young people from junk and dirty writing and was therefore no longer allowed to be displayed at magazine dealers. Radszuweit therefore decided to temporarily discontinue the paper and to publish a replacement magazine called Ledige Frauen , which had a total of 26 issues. But she saw herself as a substitute so explicitly that she gave the 1929 edition as the fourth year and had the subtitle Girlfriend . From July 1929, Die Freund resumed its publication. In March 1931, the girlfriend was once again a victim of the "trash and dirt" paragraph, this time without replacement.

On March 8, 1933, the last issue of The Girlfriend was published with number 10 of the 9th year . Like all gay and lesbian periodicals, it was then banned as "degenerate" and ceased to appear.

Target groups

In terms of content, the girlfriend was primarily aimed at lesbian women and also at transvestites via supplements and editorial articles in the actual issue . An exception was the advertising section that was also used by homosexual men or heterosexuals.

Through her regular reports, advertisements and appointments related to the lesbian subculture of Berlin, she performed functions similar to those of a city magazine . The readers of The Friend were mainly modern women who lived independently and pursued a profession.

Editors and authors

Today it can no longer be reconstructed who exactly had editorial responsibility for Die Freund and when . What is certain is that at the beginning of Die Freund between 1924 and 1925 Aenne Weber , the 1st chairwoman of the women's group of the “Federation for Human Rights”, was the responsible editor. In 1926, at the time of the insert in the friendship sheet , Irene von Behlau was in charge, from 1927 Elsbeth Killmer held this position, from 1928 to 1930 Bruno Balz . Martin Radszuweit followed him as editor in 1930, editions from 1932 onwards also show him as editor. This name hid Martin Budszko , the partner of Friedrich Radszuweit, who died in the spring of 1932, who adopted Budszko before his death.

In particular, large lead articles or discussion articles were shared across publishers by Die Freund with the Human Rights and Friendship Gazette or they were taken from a kind of fund of the publisher, articles were reprinted several times over the years in the various titles of the publisher, sometimes also shortened. These leading articles were mostly written by men, in particular by Friedrich Radszuweit, Paul Weber or Bruno Balz. Articles about the activities of the association or about current political developments were almost all written by them. It is not known how this extensive presence of male voices in a magazine for lesbian women was seen by them, whether they were editors, authors or readers.

The girlfriend was primarily aimed at homosexual women, but was not written exclusively by them. There was a relatively high fluctuation among women authors. Probably the best known regular author was Ruth Margarete Roellig . She was not only the author of the famous book Berlins lesbian women , a contemporary guide through the lesbian Berlin subculture, but had trained as an editor in 1911 and 1912 and was one of the few professional authors. Other prominent authors were activists such as Selli Engler or Lotte Hahm .

The writing for The Girlfriend was expressly not reserved for a solid group of authors. As early as 1925, the editors addressed the readers to send in their own texts. In 1927 the editors changed the structure of the magazine in order to motivate readers to participate more actively. In sections such as “Letters to 'the girlfriend'” or “Our readers have the floor”, readers had their say and were able to discuss and share their lesbian self-image and their everyday experiences. These reports are now substantial documents on the lifestyle of lesbian women in German-speaking countries at that time. In an advertisement in 1932, the editors stated that "... readers can send us manuscripts, we are happy if our readers take an active part in the paper that is published for friends in this form too."

Structure of the magazine

Volume 8, Issue 36,

September 7, 1932

The structure of the sheet was simple and remained almost the same throughout its publication: first the title sheet followed, then the editorial series began without any further structure. Finally, the classifieds section followed, which in the eight-page editions comprised one or two pages.

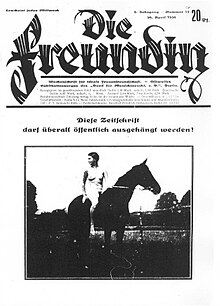

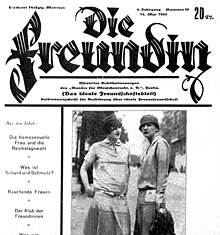

Title page

With the exception of the early days, when the editorial section already began on the front page, the front page contained photos of women, often - at the request of the readership - nudes, next to them often a table of contents or (especially between 1930 and 1933) poems .

Editorial route

A good half of the two-column editorial section consisted of novels and short stories, as well as an editorial, a discussion article, as well as poems, press reviews and letters from readers. In between there are smaller advertisements scattered around, no illustrations.

Factual texts - contents and positions

The friend offered several articles on various subjects in each issue. These included, for example, articles on historical topics relating to the history of lesbians, articles dealing with everyday problems faced by lesbian women in Germany, but also cultural, scientific or medical articles in connection with homosexuality. Contributions to literary topics or the preferably Berlin social life were also found there.

At times the magazine The Friend was also accompanied by the supplement Der Transvestit , but occasionally this part was simply integrated into The Friend through topics and areas relating to transvestites .

Analyzes and summaries of some of the central discussions can be found in the secondary literature:

Homosexuality in general

As one of the first and most popular media of the first gay and lesbian movement, Die Freund offered a central space for conveying and discussing basic questions of lesbian identity. An important point of reference were articles and opinions that were based on the sexual science authority of the time, Magnus Hirschfeld, and on his Scientific-Humanitarian Committee . Their publications were frequently quoted and mentioned with praise, and for the first two years the WhK's newsletter was also a supplement to The Friend .

Over the years and different authors (and according to the association's line), the understanding of homosexuality as an innate, natural predisposition was almost consensual, the homosexuals then formed a "third gender", a term by Johanna Elberskirchen , whose text "The love of the third gender ”Under the title“ What is homosexuality? ”Was published in 1929 in Die Freund . The authorship of The Girlfriend was thus in line with the modern sexual science theories of the time. From this recognition of the naturalness of homosexuality, it came to the conclusion that homosexuals, and thus also lesbian women, were entitled to full social recognition.

At this point the paper repeatedly came into disagreement with Magnus Hirschfeld around 1930. Hirschfeld has been criticized for repeatedly contextualizing homosexuality as inferior, abnormal, or pathological in legal proceedings such as elsewhere, thereby helping to stigmatize homosexuals.

Lesbian self-image

Despite the participation of men and the cross-association of topics, Die Freund was a medium in which lesbian women found the necessary space to debate and define their self-image, their roles and their goals.

The thesis of the “third sex”, which is on an equal footing with the two heterosexuals, also formed the point of reference here. For example, in an intensive discussion that addressed the relationship between homosexual and bisexual women. More or less unanimously in the rejection, the discussion culminated in allegations that the bisexual woman was “vicious” and “perverted” and resulted in appeals from readers such as “Hands off those two natures who enjoy both sexes out of lust for lust! - You are kicking our love in the dirt! ”Or“ This committee of women, this scum is what really homosexual women should fight against ”. The background to this strong rejection was the understanding of homosexuality as clearly defined biologically, which was attacked by the apparent ambiguity of bisexual lifestyles.

The widespread role model of "Bubi" vs. "Lady" or "virile" vs. “Feminine” lesbian (similar to the later butch-and-femme role distribution) was then discussed to what extent it perpetuated and strengthened clichés that, in the context of their own interests and the emerging women's movement, were understood to be more likely to be overcome.

Women's movement

General texts on the women's movement were found very sporadically in The Girlfriend . Die Freund did not close all ranks with the women's movement, which was gaining strength at the time , although she started in 1924 with the self-image that she would “stand up for equal rights for women in social life”. None of the issues of the women's movement discussed at the time found expression there, whether contraception, abortion, family or divorce law. The focus of women's movement issues was always clear positioning from the perspective of homosexual women and these were asserted as a distinctive feature even if a topic such as the demand for better professional advancement could have been linked to existing issues of the women's movement.

Allegedly gender-typical peculiarities of women were neither accepted by the homosexual women nor questioned as an attribution. They were quite accepted, albeit only in connection with the goal of achieving equality for homosexual women with men on the basis of their male sexual character. Here, too, one can see the understanding shimmer through, not to see oneself as subject to a male-female dualism, but to see oneself as one's own separate gender.

Homosexual politics

A naturally central theme of The Girlfriend were again and again social and political obstacles for homosexual women, because despite the liveliness of gay and lesbian life in Berlin during the Weimar Republic , lesbian lifestyles were not socially accepted. Throughout the history of the publication, this remained an occasion for corresponding political texts, whether as reports and analyzes of social and political conditions, insofar as they specifically concerned homosexuals, or as mobilizing calls and activist attempts to change them. The response from the readership to such calls was apparently muted.

The rooting of The Girlfriend in an association dominated by male homosexuals led to the regular publication of calls to campaign for the abolition of § 175 . This did not directly affect homosexual women, because only male homosexuals were covered by Section 175. Again and again, however, a possible tightening of the paragraph was discussed so that it should also include female homosexuality. Calls for its abolition therefore appeared regularly in all member magazines of the BfM, in some cases without any explicit reference to female homosexuality.

In spite of regular articles on party political issues, Die Freund remained rather undecided here. Although Irene von Behlau recommended the election of the Social Democratic Party in her article "The homosexual woman and the Reichstag election" of May 14, 1928, a kind of neutrality requirement had applied since 1930, as statistics from 1926 about the BfM had made it clear that the members belong to both left and right parties. The only recommendation that remained was therefore the call to vote only for parties who would campaign for the abolition of Section 175. In August 1931, the editor Friedrich Radszuweit published a "Letter to Adolf Hitler " in Die Freund , in which he asked him, in view of some recently known cases of "same-sex lovers" in the NSDAP , among them the "most capable and best, who are active in the party ” to let the party's deputies vote in the Reichstag for the abolition of § 175.

However, all attempts to politically involve the readers of The Girlfriend and to activate them for common goals seem to have failed. Correspondingly active people regularly complained about the alleged passivity of the readers.

Fiction

Around half of the fiction part of the booklet consisted of short stories, serial novels and poems about lesbian love. In addition, there were always book recommendations and reviews of books, not a few of which were published by “Friedrich Radszuweit Verlag”.

The corresponding texts contributed particularly to the popularity of The Girlfriend . They did not come from a professional literary pen, but from those of employees or readers of Die Freund . In literary terms, these works are mostly to be classified as trivial and artistically of no great importance. However, they were accessible to depict lesbian worlds and to formulate utopias, thematized love experiences, the problems of finding a partner, but also the discrimination by the environment, but always with "positive identification patterns" in which these difficulties are presented as surmountable. Doris Claus, for example, emphasizes the emancipatory value of the work in her analysis of the novel “Arme kleine Jett” by Selli Engler, which appeared in sequels in Die Freund in 1930 . By drawing a lesbian way of life without massive conflicts with the social environment and society in the realistically portrayed Berlin artist milieu, he created a utopia and offered the possibility of identification.

Hanna Hacker and Katharina Vogel even understand the stylistic devices used in trivial literature as constitutive for this purpose, because the use and processing of "found stereotypes by lesbian women also develop the dynamism to stabilize their own culture".

Advertisement section

The end of a magazine was always the advertisement section. In addition to various forms of personals, it mainly contained job advertisements, event notices and advertisements for bars and books. Such advertisements were only accepted by members of the Federation for Human Rights, which in turn led to the fact that many restaurants and venues in particular became members in order to get the opportunity to advertise. This method strengthened the Bund and its weight in the gay and lesbian movement, especially since the readership was encouraged to only visit those locations recommended by the Bund.

Personals

Two forms of personals can be distinguished. On the one hand, there are advertisements in which lesbians, gays or transvestites are looking for partnerships. Lesbians used the contemporary codes of their subculture, recognizable in formulations such as “Miss, 28 years old, is looking for an educated friend”, “Lady wants genuine friendship with a well-off lady” or “Where do friends from higher circles meet, possibly privately?”.

A very different type of frequent form of the contact advertisement is that after so-called camaraderie. This was about marriages between a homosexual woman and a homosexual man. In times of criminal prosecution, it was hoped that the status of marriage would provide some protection from persecution. The intention was unmistakable in advertisements like "27 year old, of good origin, double orphan, representative, seeks comradeship marriage with wealthy lady (also business owner)".

Event information

The last two pages also contained numerous event notices and advertisements from lesbian bars, mostly from Berlin. Meetings and celebrations of the so-called women's clubs were also reflected in the editorial section, as they were reported in retrospect. These women's clubs were evidently large, according to the report, 350 members were present at Lotte Hahm's 4th foundation festival of the women's club “Violetta”. The ladies' club " Erato ", which advertised in The Girlfriend and whose club meeting was also reported there, rented dance halls with a capacity of 600 people for its events.

meaning

At the time of the Weimar Republic, a lesbian self-image was negotiated for the first time as part of the first homosexual emancipation movement. Berlin, as the center of homosexuals from all over Europe, provided ideal conditions for this. In addition to the numerous magazines and periodicals devoted to homosexuality in general (albeit mostly with a male focus), this also led to a magazine market for specifically lesbian interests. Three such items are detected so far, in addition to the girlfriend , the love of women (1926-1931), the parallel as Women in Love and in the short term than women love and life appeared (1928) and later in the Garçonne opened (1930-1932), as well as the BIF - Sheets of Ideal Frauenfreundschaft (probably 1926–1927). Among these, the girlfriend , founded in 1924, was the first (worldwide) lesbian magazine. Since it appeared almost continuously until the general ban on all homosexual magazines in 1933, it was also the longest-lived lesbian publication of the Weimar Republic.

Contemporary reception

In anonymous interviews with older lesbians that Ilse Kokula conducted in the mid-1970s, the meaning of the friend for her readers is more clearly outlined. Marte X. spoke of "our newspaper", "if something was somehow, it was always in the girlfriend". "We bought them under the counter [...] with fear [...] we always had to hide them all". GM stated “I bought The Girlfriend as often (rarely!) As I could. There were advertisements in it, where and what was going on. ”And Branda reported:“ I bought it for the first time where I read it. Then I bought it where I was unknown. [...] And then you felt like you had a bomb in your pocket. [...] I read them where nobody bothered you. And put it in the blouse so that nobody could see it. ”But she denied regular reading,“ only occasionally ”,“ it cost 50 pfennigs. That was a lot. " Branda later also sent a poem to the editorial staff, which was printed on the title page with her full name, whereupon she withdrew the poem because she had received “remorse”.

Readers' voices handed down individually support the importance of the magazine, also and in a special way beyond Berlin. Espinaco-Virseda quotes a reader as saying: “Through her I received valuable information about my own nature and also learned that I was in no way unique in this world.” A reader from Essen wrote: “For years I have Looking in vain for an entertainment reading that brings people of our kind closer to one another through word and writing, the sisters of our nature illuminate hours of solitude until I visit Hildesheim - a small town, please! and strictly religious at that! - «The girlfriend» fell into my hands. ”Another voice spoke of the girlfriend as“ a magazine that I have been missing for a long time and that is able to tell me about the lonely hours of which I am in the Unfortunately too many provincial are destined to comfort. How do I envy my fellow species and friends in Berlin! [...] ".

The voice of Charlotte Wolff , then living as a lesbian in Berlin, differed from this after reading the booklet for the first time in 1977: “I had never met“ The Girlfriend ”at the time it was published, a sure sign of the mystery that surrounded her appearance, even though it was homosexual Movies and plays were en vogue in the 1920s. “The girlfriend” was obviously an “illegitimate child” who did not dare to show his face in public. The lesbian world it depicted had little in common with the gay women I knew and the places I frequented. Your readers came from a different class who loved, drank and danced in another world. "

Today's reception

From today's perspective, The Girlfriend is “probably the most popular” of the lesbian magazines of the time and is seen as a “symbol of lesbian identity in Berlin in the 1920s”. Florence Tamagne speaks of it as a "well-received magazine that became a symbol of lesbianism in the 1920s". Günter Grau rates it as "the most important magazine for lesbian women in the Weimar Republic of the 1920s". Angeles Espinaco-Virseda characterized Die Freund as a “publication in which science, mass culture and subculture overlap”, one of the magazines “that addressed women directly, articulating their desires and giving them modern new concepts - and choices - for gender roles, sexuality, partnerships and consequently offered opportunities for identification. "

The " UKZ: our little newspaper from and for lesbians ", founded in 1975 by the L74 group (among others with Kitty Kuse ), followed on from The Girlfriend and thus drew a line from the first lesbian movement of the Weimar Republic to the lesbian movement of the Federal Republic.

State of research

For a long time, the same applied to Die Freund , which basically applies to all journals of homosexual women of the time: "With the exception of a few essays and unpublished theses, they have hardly been considered by historical research." With Heike Schader 's work "Virile, Vamps and Wilde Veilchen" from 2004, a more extensive work was presented for the first time, which carried out a scientific sifting through the source material. Up until now there had only been one profile on The Girlfriend in an exhibition catalog and two university works. As the most popular and widespread magazine for homosexual women of the Weimar Republic, it has received additional attention since then, so that in 2010 it could already be said about it, "The content of the 'girlfriend' has already been processed very well in several scientific papers and publications."

proof

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Julia Hürner: Living conditions of lesbian women in Austria and Germany - from the 1920s to the Nazi era (PDF; 657 kB) , Dissertation 2010, pp. 38-43 & 46-52, accessed April 28, 2013

- ↑ The Girlfriend , No. 5, Volume 2, March 1, 1925, title page

- ↑ The Girlfriend , Issue Number 20, Volume 3, October 17, 1927, title page

- ^ A b The Girlfriend , Issue Number 36, Volume 8, September 7, 1932, title page

- ↑ Julia Hürner: Living conditions of lesbian women in Austria and Germany - from the 1920s to the Nazi era (PDF; 657 kB) , dissertation 2010, p. 35, accessed on May 9, 2013

- ↑ a b c d e f Heike Schader: Virile, vamps and wild violets. Sexuality, Desire and Eroticism in the Magazines of Homosexual Women in Berlin in the 1920s. (Also: Hamburg, University, dissertation, 2004), Ulrike Helmer Verlag, Königstein / Taunus 2004, ISBN 3-89741-157-1 , pp. 43-48 & 63-72

- ↑ a b c d e f g Katharina Vogel: On the self-image of lesbian women in the Weimar Republic. An analysis of the magazine “Die Freund” 1924–1933. In: Berlin Museum (ed.): Eldorado. Homosexual women and men in Berlin 1850–1950. , 1984, ISBN 3-88725-068-0 , pp. 162-168

- ↑ Petra Schlierkamp: The Garçonne In: Berlin Museum (Ed.): Eldorado. Homosexual women and men in Berlin 1850–1950. , 1984, ISBN 3-88725-068-0 , pp. 169-179

- ↑ a b c d e f Stefan Micheler: Magazines, associations and bars of same-sex desirous people in the Weimar Republic , extended version of a chapter of the dissertation self-images and external images of the "others". Men desiring men in the Weimar Republic and the Nazi era , Konstanz: Universitätsverlag Konstanz 2005, online (PDF; 506 kB), pp. 31–34, 2008

- ^ Günter Grau: Lexicon on Homosexual Persecution 1933-1945: Institutions - Competencies - Fields of Activity , ISBN 978-3-8258-9785-7 , 2010, p. 329

- ^ The girlfriend , title page issue number 10, 4th volume, May 14, 1928, online

- ↑ a b c Günter Grau: Lexicon on Homosexual Persecution 1933-1945: Institutions - Competencies - Fields of Activity , ISBN 978-3-8258-9785-7 , 2010, p. 59

- ↑ Aenne Weber. In: Personalities in Berlin 1825-2006. Memories of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender and intersex people. Published by the Senate Department for Labor, Integration and Women, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-9816391-3-1 , p. 76 f.

- ↑ Heike Schader: Virile, Vamps and Wild Violets. Sexuality, desire and eroticism in the magazines of homosexual women in Berlin in the 1920s , Ulrike Helmer Verlag , Berlin 2004, ISBN 9783897411579 , p. 246

- ^ Doris Claus: Of course, lesbian during the Weimar Republic. An analysis of the magazine "Die Freund" , Bielefeld, 1987, p. 30

- ↑ Der Nationalhof (1924–1932) - A ballroom of the homosexual movement In: Andreas Pretzel : Historical places and dazzling personalities in the Schöneberger Regenbogenkiez - From Dorian Gray to Eldorado , undated (2012?), P. 86

- ↑ a b Mailbox In: Die Freund , Issue 37, Volume 8, September 7, 1932, Page 7

- ↑ a b c d Angeles Espinaco-Virseda: “I feel that I belong to you” - Subculture, Die Freund and Lesbian Identities in Weimar Germany , In: Spaces of identity: tradition, cultural boundaries & identity formation in Central Europe, 4: 1, pp. 83-100, 2004, online

- ↑ Günter Grau: Lexicon on the persecution of homosexuals 1933–1945: Institutions - Competencies - Areas of Activity , ISBN 978-3-8258-9785-7 , 2010, pp. 235–236

- ^ Doris Claus: Of course, lesbian during the Weimar Republic. An analysis of the magazine "Die Freund" , Bielefeld, 1987, pp. 76-93

- ↑ a b Heike Schader: Virile, Vamps and Wild Violets. Sexuality, Desire and Eroticism in the Magazines of Homosexual Women in Berlin in the 1920s. (Also: Hamburg, University, dissertation, 2004), Ulrike Helmer Verlag, Königstein / Taunus 2004, ISBN 3-89741-157-1 , p. 41

- ↑ Leidinger, Christiane: An “Illusion of Freedom” - Subculture and Organization of Lesbians, Transvestites and Gays in the Twenties [online]. Berlin 2008. In: Boxhammer, Ingeborg / Leidinger, Christiane: Online project lesbian history. , Accessed April 29, 2013

- ↑ Heike Schader: The vicious woman , in: Claudia Bruns, Tilmann Walter (ed.): From lust and pain: a historical anthropology of sexuality. , 2004, ISBN 3412073032 , p. 241

- ↑ Karina Smits: Die Freund and Other Relationships: A Proposal for a Comparative Study of the Role of Lesbian Magazines within the Process of Cultural Transfer and Transmission , In: Petra Broomans, Sandra van Voorst, Karina Smits: Rethinking Cultural Transfer and Transmission: Reflections and New Perspectives , 2012, ISBN 9491431196 , pp. 131-137

- ↑ Ilse Kokula: "Years of happiness, years of suffering: Conversations with older lesbian women", 1986, Spring Awakening Publishing House - Quotes Marte X .: P. 68-75, GM: P. 90, Branda: P. 95-96

- ↑ Kirsten Plötz: About "conspecifics" and other appropriations of sexual science models of female homosexuality during the twenties in the 'province' In: Ursula Ferdinand / Andreas Pretzel / Andreas Seeck (eds.): Verqueere Wissenschaft? On the relationship between sexology and the sex reform movement, past and present. , 1998, ISBN 3825840492 , pp. 129-137

- ↑ "[...] I had never come across the girlfriend when it had appeared, a sure proof of the secrecy surrounding its publication, though homosexual films and plays had been in vogue in the twenties. The girlfriend had obviously been an "illegitimate child" which did not dare to show its face openly. The lesbian world it depicts had little in common with the homosexual women I knew and the places I frequented. Its readers must have been of a different class who loved, wined and danced in a different world. [...] “ Quoted from: Maggie Magee, Diana C. Miller: Lesbian Lives: Psychoanalytic Narratives Old and New , 2013, ISBN 1134898665 , p. 351

- ↑ : "The girlfriend, a well received magazine that became the symbol of lesbianism in the 1920s." Florence Tamagne: A History of Homosexuality in Europe, Berlin, London, Paris 1919–1939, Vol. 1 , 2006, p. 77

- ↑ Kirsten Plötz : "Where was the movement of lesbian rubble women" in: "Research in Queer Format: Current Contributions from LGBTI *, Queer and Gender Research", pp. 71–87, ed. by Federal Foundation Magnus Hirschfeld, 2014

- ↑ Heike Schader: Virile, Vamps and Wild Violets. Sexuality, Desire and Eroticism in the Magazines of Homosexual Women in Berlin in the 1920s. (At the same time: Hamburg, University, dissertation, 2004), Ulrike Helmer Verlag, Königstein / Taunus 2004, ISBN 3-89741-157-1 , p. 12

- ↑ Julia Hürner: Living conditions of lesbian women in Austria and Germany - from the 1920s to the Nazi era (PDF; 657 kB) , dissertation 2010, p. 102, accessed on May 9, 2013

literature

- Heike Schader: Virile, vamps and wild violets. Sexuality, Desire and Eroticism in the Magazines of Homosexual Women in Berlin in the 1920s. , Helmer, Königstein im Taunus 2004, ISBN 3-89741-157-1 (also dissertation at the University of Hamburg , 2004)

- Katharina Vogel: On the self-image of lesbian women in the Weimar Republic. An analysis of the magazine “Die Freund” 1924–1933. In: Berlin Museum (ed.): Eldorado. Homosexual women and men in Berlin 1850–1950. History, everyday life, etc. Culture (exhibition at the Berlin Museum, May 26 - July 8, 1984) , Frölich and Kaufmann, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-88725-068-0 , pp. 162–168