Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām

The Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām or Fedajin-e Islam ( Persian فدائیان اسلام'Those who sacrifice themselves for Islam') was a secret Islamic organization that carried out several attacks on high-ranking figures from science and politics in Iran from 1945 to 1955 . It was founded in 1945 by the 22-year-old theology student Navvab Safavi . Safavi wanted to “cleanse corrupt individuals” from Islam through carefully planned assassinations. Members of his organization were mainly young men and young people from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. The model for the group was the military branch of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood founded in 1928 , with which there were also personal relationships.

founding

Navvab Safavi was born in Tehran in 1924 and studied in Najaf in what is now Iraq. Safavi kept in close contact with Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kaschani , who, as a high-ranking clergyman, helped initiate the Fedayeen Islam.

The demands of the Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām were:

- the establishment of an Islamic government under the leadership of an imam,

- Application of Sharia law ,

- Purification of the Persian language from un-Islamic vocabulary,

- Pan-Islamism and Nationalism ,

- Nationalization of oil,

- Jihad against Western powers and spreading the ideology of martyrdom,

- the prohibition of alcohol, tobacco, opium, films and gambling,

- the ban on wearing western clothing,

- the requirement to wear the chador for women

- and the removal of all non-Muslim subjects such as B. Music, from school lessons.

Assassinations

Ahmad Kasravi (April 28, 1945)

The first assassination attempt successfully carried out by the Fedayeen-e Islam was against Ahmad Kasravi . Kasravi, a historian, linguist and philosopher who advocated democracy and the rule of law, had published several articles against the obscurantism of Shiite Islam. Safavi met Kasravi and discussed Islam with him. On April 28, 1945, Safavi shot Kasravi with a revolver. The first shot, however, was not fatal. With the gun stuck, Kasravi escaped and survived the assassination attempt.

A little later, at the instigation of Prime Minister Ahmad Qavam and other leading politicians, a lawsuit was brought against Kasravi for "anti-Islamic views". On March 11, 1946, Kasravi and his assistant went to the Ministry of Justice to testify about the allegations in an office on the third floor of the Ministry of Justice. But it shouldn't come to that. Two members of the Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām, the two brothers Hosein and ʿAli Mohammad Emāmī, entered the room and stabbed Kasravi. Kasravi succumbed to his injuries. The two perpetrators were immediately arrested and sentenced to death. However, the death sentence was not carried out; rather, the perpetrators were released due to pressure from the Tehran bazaar and the advocacy of Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani . From then on, the group formed an alliance with Kaschani. So the Fedāʾiyān brought together with him in May 1948 several thousand people for a solidarity rally with the Palestinian Arabs.

Mohammad Reza Shah (February 4, 1949)

The next assassination attempt on February 4, 1949 was aimed at Mohammad Reza Shah himself. It later emerged that the assassin Nasser Fakhr Araϊ had gained access to the university campus where the attack took place using a press card issued by the newspaper Partcham Islam (The Flag of Islam). The newspaper was published by a relative of Abol-Ghasem Kashani . Since the assassin was shot on the spot, the perpetrators of the attack could no longer be determined. Abol-Ghasem Kashani was expelled from the country and went into exile in Lebanon .

Abdolhossein Hazhir (November 5, 1949)

If the assassination attempt on Mohammad Reza Shah in February 1949 failed, the group had more success on November 5, 1949 in the Sipah Salar Mosque. It was here that the fatal shots of Hosein Emāmī met Prime Minister Abdolhossein Hazhir . Emāmī was arrested a second time and this time also remained in prison.

On intervention of Mohammad Mossadegh with Mohammad Reza Shah , Abol-Ghasem Kaschani was allowed to return to Iran in June 1950. Mossadegh personally greeted Kashani at Tehran airport and Kashani, who had been elected to parliament as a member of the National Front , was elected President of Parliament.

Ali Razmara (March 7, 1951)

The next attack by the Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām was on Prime Minister Ali Razmara . The fatal shots from Chalīl Tahmasbi struck Razmara on March 7, 1951 in front of the Soltani mosque in the bazaar of Tehran. Chalīl Tahmāsbi was first arrested and sentenced to death. Ayatollah Kaschani declared the murderer Razmaras the "savior of the Iranian people" and demanded his immediate release from prison. Kaschani had previously sentenced Razmara to death in a fatwa.

A month later, Mohammad Mossadegh had become prime minister and one of his first acts was to release Chalīl Tahmāsbi from prison. Mossadegh had passed a law in parliament that overturned the death sentence against Tahmasbi and declared Tahmāsbi a popular hero.

After Mossadegh's resignation in July 1952, it was Kashani who ultimately demanded that the Shah reinstate Mossadegh as prime minister, otherwise he would “personally raise the sharp sword of the revolution against Mohammad Reza Shah”. The Shah relented and Mossadegh was again prime minister.

In his second term, Mossadegh broke with Kashani. As requested by Kashani, Mossadegh refused to introduce Sharia law and, in the upcoming parliamentary elections, to give preferential treatment to candidates selected according to Islamic principles, including Kashani's sons. Mossadegh turned away from Kashani, who wanted to establish an Islamic state in Iran, and turned to the Tudeh party , which in turn led Kashani to support Mohammad Reza Shah and General Fazlollah Zahedi . During the days when Mossadegh was overthrown, Kashani kept in close contact with Zahedi and offered shelter to his son Ardeshir Zahedi in his home.

On March 19, 1951, Ahmad Zanganeh, the dean of the law faculty at Tehran University, was shot at. Although the assassin had no connection with the Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām, this group was held responsible. In June 1951 the entire leadership of the movement including Nawwāb was arrested.

Hossein Fatemi (February 15, 1952)

During a commemoration of the fourth anniversary of Mohammad Masoud, editor of the newspaper Mard-e Emruz (The Man of Today) , who was murdered on February 15, 1948 , the future Foreign Minister Hosein Fātemi, a member of Prime Minister Mossadegh's cabinet , was attacked with a knife and seriously injured. The assassin was a 15 year old student who identified himself as a member of the Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām. Although Fātemi survived the attack, he spent nearly a year in the hospital and never fully recovered from his serious injuries. Slogans such as “Death to the enemies of Islam” and “Immediate freedom for His Holiness Nawwāb Safawi and Master Tahmāsbi” were engraved on the perpetrator's weapon. Nawwāb was not released until early February 1953.

Hossein Ala (November 22, 1955)

General Zehadi showed his appreciation to Kaschani, and his son Mostafa Kaschani was elected as a member of parliament. However, cooperation between Kashani and the government under Prime Minister Zahedi was soon to be tarnished. Kashani was a bitter opponent of the new consortium agreement, which gave an international consortium of oil companies the rights to extract and market Iranian oil. Kashani was arrested for continuing threats against the Shah, but released a few weeks later. A little later, Kaschani's son, Mostafa Kaschani, was killed in an accident. Mostafi Kashani's death was to have consequences for the Islamist opposition. During the funeral ceremony on November 22, 1955, Prime Minister Hossein Ala was assassinated . Ala survived, but this time Navvab Safavi and other members of Fedayeen-e Islam were arrested, sentenced to death, and executed in January 1956.

After Navvab Safavi's death, the remaining members of the Islamist group turned to Khomeini, who supported the rebuilding of the Fedayeen-e Islam. The future judge of the Islamic Republic of Iran Sadegh Chalkhali is also associated with the rebuilding of Fedayeen Islam. The Fedajin-e Islam became part of the Islamic Revolutionary Associations ( Jamiyathaye Mu'talefeh-ye Eslami ) as part of the Islamic Revolution .

Hassan Ali Mansour (January 27, 1965)

The name of the Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām again in connection with the assassination attempt on Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansour on January 27, 1965. Mansour is said to have been sentenced to death by a secret Islamic court of Morteza Motahhari and Mohammad Beheschti after Mansour expelled Khomeini from the country and sent him into exile. The executing organization was the so-called “Party of Islamic Nations” ( Hezb-e Mellal-e Eslāmi ). However, the investigation revealed that many of the members of the organization had previously been members of the Fedāʾiyān-e Eslām. Akbar Hāschemi Rafsanjāni , who later became President of the Islamic Republic of Iran , admitted after the Islamic Revolution that he and others had commissioned the murder of Mansour. He got hold of the pistol that was used in the Mansour murder. To prove it, he presented the pistol he had taken as a personal memento. Asadollah Badamchian said of the assassination attempt on Mansour and Mohammad Reza Shah on April 10, 1965:

“In the case of the revolutionary attacks on the Shah or Mansour, we first asked the ulama for the verdict . An inquiry was made with the Imam (Khomeini) before he was sent into exile, but he stated that the time was not yet ripe. He had asked Ayatollah Beheschti and Motahhari to speak for him in his absence. An inquiry was made to them and they confirmed the judgment. "

Mohammad Reza Shah (April 10, 1965)

The second assassination attempt on Mohammad Reza Shah on April 10, 1965 by Reza Schams Abadi, a member of the Imperial Bodyguard, was supposed to hit the Shah in the entrance area of his palace. Armed with a submachine gun, he fired into the entrance hall, killing two bodyguards and wounding another before collapsing, hit by bullets. The ex-general Teymur Bachtiar, who was in exile, appeared as the alleged client in the investigation into the backers . Ahmed Mansuri and Ahmed Kamerani were sentenced to death at the trial of six conspirators, Parvir Kiktschah received life imprisonment, and other defendants were acquitted. The death penalty for the two main defendants was later commuted to life imprisonment by a decree from Mohammad Reza Shah. All of the convicts were released after a few years.

From today's perspective it becomes clear why those accused of the conspiracy were not executed but pardoned and released from prison after a few years. The conspirators were not, as had been claimed in the trial, to be assigned to the left-wing scene. Rather, Shamsabadi had been contacted by members of Fedayeen-e Islam who had murdered Prime Minister Mansur just three months earlier. Khomeini was deported to Turkey six months before the attack on Mansur. The assassination attempt on Mohammad Reza Shah was obviously intended to hit the top representative of the political system that was ultimately responsible for the condemnation and exile of Khomeini.

Islamic Revolution

During the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the members of the Fedayeen-e Islam, along with the Hezbollahis, were considered to be Khomeini's foot soldiers, who formed the fundamentalist wing of the revolutionaries. Many former members of Fedayeen-e Islam are now part of the government apparatus of the Islamic Republic of Iran. After the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the Fedayeen-e Islam were re-established by the infamous Sadegh Khalkali .

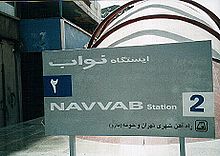

A station on the Tehran subway and a training facility for the Iranian Revolutionary Guard is named after the founder of Fedajin-e Islam, Navvab Safavi .

See also

literature

- S. Behdad: "The Islamic Utopia of Navvab-Safavi and the Fada'ian-i Islam" in Middle East Studies 33 (1997) 40-65.

- Farhad Kazemi: “The Fada'iyan-e Islam : Fanaticism, Politics and Terror” in Said Amir Arjomand (ed.): From Nationalism to Revolutionary Islam . London / Basingstoke: Macmillan 1984. pp. 157-176.

- Farhad Kazemi: Art. "Fedāʾīān-e eslām" in Encyclopædia Iranica Vol. IX, pp. 470–474. Available online here: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/fedaian-e-esla

- NR Keddie and AH Zarrinkub: Art. "Fidāʾiyyān-i Islām" in The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition Vol. II. 882a-883a.

- Baqer Moin: Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah . New York: St. Martin's Press 2000.

- Y. Richard: "L'organization des Feda'iyan-e Eslam: Mouvement Integriste Musulman en Iran, 1945-1956" in O. Carré and P. Dumont (eds.): Radicalismes Islamiques, I: Iran, Liban, Turquie . Pari 1985. pp. 23-82.

- Syed Muhammad Ali Taghavi: "Fadaeeyan-i Islam: The Prototype of Islamic Hard-Liners in Iran in Middle Eastern Studies 40 (2004) 151-165.

- Amir Taheri: The Spirit of Allah . Bethesda, Md .: Adler & Adler 1985.

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 160.

- ↑ Amir Taheri : The Spirit of Allah , 1985, p. 98.

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 168.

- ↑ See Keddie / Zarrinkub 883a.

- ↑ Ulrich Gehrke, Harald Mehner: Iran. Erdmann publishing house. 1975. page 196

- ^ Karl-Heinrich Göbel: Modern Shiite Politics and State Idea. Page 162

- ↑ Abrahamian, Ervand: Iran between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press, 1982, p. 259

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 161.

- ↑ Keddie / Zarrinkub 882b.

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 162.

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 163.

- ↑ See Kazemi 164.

- ↑ Abbas Milani: Eminent Persians. Syracuse University Press, 2008, p. 346.

- ↑ Ervand Abrahamian: 'A History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p 116

- ↑ Abbas Milani: Eminent Persians. Syracuse University Press, 2008, p. 348.

- ↑ Cf. Kazemi 164f.

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 166.

- ↑ http://www.mohammadmossadegh.com/biography/hossein-fatemi/

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 166.

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 166.

- ↑ Baqer Moin: Khomeini , 2000, p. 224

- ↑ See Kazemi 1984, 166f.

- ↑ Gholam Reza Afkhami: The life and times of the Shah. University of California Press, 2009, p. 377

- ^ Gérard de Villiers: The Shah . P. 382 ff.

- ↑ Gholam Reza Afkhami: The life and times of the Shah. UC University Press, 2009. pp. 376f.

- ↑ Baqer Moin: Khomeini, 2000, p. 224.