Little things from the episcopal life

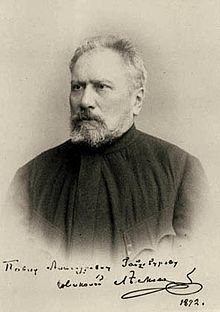

Snacks from the bishop Life ( Russian Мелочи архиерейской жизни , Melotschi archijereiskoi schisni ) is a narrative (Russian literary scholars speak in the case of a Otscherk - an outline or a sketch) of the Russian writer Nikolai Leskov , which from 1878 to 1880 in the newspaper Novosti and appeared in the magazine Historischer Bote . The text gathers anecdotes about bishops who officiated in Russian eparchies during the author's lifetime, i.e. in the 19th century .

In 1888 Adolf Marks brought out a ten-volume Leskow edition in Russian. The sixth volume with the little things had to be withdrawn on the instructions of the censors. The text was on the index of prohibited scriptures in Russia until 1905.

In Leskov's portrait collection, the reader will not only find entertaining information about some of the pastors of the Russian Church. Leskow digs partially deeper; introduces bishops who wanted to remain human but had to rule. Many a truly Solomonic judgment, passed by such a shepherd, absolutely presupposes human size and seldom clings to the letters of the applicable law.

content

The strict bishop Nikodim had cracked down on Leskov's hometown Oryol on the Oka . Nikodim had sent a cousin of Leskov to the military. Leskov's father, who did not care much for the monastic clergy, went to Nikodim and complained fearlessly about the bishop's decision. Leskov's father's intervention had no consequences for the family.

At that time, the Russian bishops had jurisdiction over their subordinate clergy. Archbishop Smaragd Kryschanowski von Oryol, who was “too blooded and obese”, kept the young village sexton Lukjan, a womanizer, waiting a long time for his trial. During the waiting time Lukjan had to saw wood for the bishop's house. Smaragd, who wanted to treat his obesity himself, often mingled with those waiting for his court ruling and sawed wood with one of the delinquents for physiotherapy reasons. Usually the person assigned to saw would then place an easy-to-saw trunk on the sawhorse for the bishop. But not Lukjan. Smaragd - not used to therapeutic gymnastics on such a knot - then beat Lukjan and otherwise released the womanizer from prison with impunity.

Archbishop Smaragd wasn't the only one who beat up his subordinates. Bishop Innokenti of Tauria hit one of his monastery servants who could be bought with his hands and kicked him.

The bishop Warlaam of Penza was once outwitted by a woman. The peasants of a village in the Governorate of M. suffered from the greed of a priest. The village owner, Countess Wiskonti, had promised her farmers a remedy and had approached Warlaam outside of office hours. The bishop showed himself closed until the countess reached her goal with a lie. The Wiskonti reproduced a fictitious dialogue with the priest. The priest replied: 'The bishop won't tear his leg off because of us, and after all we have to eat and drink.' The priest was deposed.

Other clergymen were unimpressed by women. Bishop Ioann von Smolensk did not let two ladies eager for idle chatter in front.

Leskov's brother, a Kiev gynecologist, was once urgently called to see His Eminence Porfiri Uspenski . The bishop had the gynecologist treat his constipation .

Filaret Amfiteatrow , Metropolitan of Kiev, was so annoyed by some of the offenses of his subordinates that, as Supreme Court Lord, he personally led the trial and announced the verdict. During the trial he spoke aside in the direction of his assessor: "... he deserves it [the punishment], the fool, but I'm afraid I might even be too tough - eh?" When he was subsequently accused of undue indulgence, Filaret contradicted: " Then why did the poor guy cry? "

In the same breath as the benevolent Filaret of Kiev, Leskov names Bishop Neofit a kind-hearted monk, indulgent and philanthropic bishop who read Stschedrin's satires before falling asleep . Neofit had almost no money, laughed at the bigots who were in vain in favor of him, listened with obvious pleasure to the secular singing of young people, wanted to fish crucian carp in the village pond in the evening and asked for Christ's dish (baked fish).

"Bishop Polikarp , a strict monk and eccentric, but at the same time a very good person" punished a sexton. The displaced had taken revenge on a wealthy couple by denouncing them. The couple's marriage was then declared invalid because the cousin was married to the cousin. Now the couple's children were considered illegitimate. The woman turned to Polikarp with the question: Should the denounced people pay half their fortune to a Petersburg “legal specialist” who wants to twist the court judgment? Polikarp replied no. The Petersburg cutthroat got nothing, because - according to Polikarp - not everything that the courts decide should be taken seriously.

Metropolitan Filaret Drozdov was confronted with an even more intricate case . A widower took his sister-in-law into the household to look after his children and got the 23-year-old pregnant. The metropolitan cared little about the laws of the orthodox church and mentioned in conversation a feasible way in which the couple's marriage could be realized. Leskow reports another story from the work of the Metropolitan Filaret Drozdov. When a police general criticized the liturgy in a Moscow church, he made the general stand at attention.

Finally, Leskow makes a contribution to tradition when he remarks "that the written legacy of bishops is in most cases secured immediately after the death of its owner and the researcher ... never gets his hands on it" and the author in the context of the An attempt at a bibliography of the writings of Metropolitan Isidore - during his lifetime - starts.

Only the bishops narrative worked out in the text were listed. Leskov also mentioned others:

- Augustin of Ufa (1768–1841),

- Grigori of Kaluga (1784–1860),

- Filaret Filaretow (1824-1882),

- the scholar Makari of Lithuania (1816–1882),

- Arseni (1795–1876), Metropolitan of Kiev from 1860,

- Filofei Uspenski (1808-1882) and

- Mitrofan of Voronezh (1623–1703).

When Filaret Amfiteatrow - who later became the Metropolitan of Kiev (see above) - was still Archimandrite , Augustin von Ufa is said to have beaten him regularly. In Kaluga, Bishop Grigori is said to have been attacked by a dissatisfied sexton. Filaret Filaretov, who later became the bishop of Riga , was cursed in the Kiev cathedral .

Quote

"Where people easily believe everything, they also easily lose all belief."

reception

- 1969: Reissner thinks the text is not an attack on the upper Russian clergy. After reading it, the reader can no longer show the orthodox clergy the necessary respect.

German-language editions

First translation into German:

- Little things from the episcopal life. Images according to nature. German by Günter Dalitz. P. 577–747 in Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. The enchanted pilgrim. 771 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1969 (1st edition)

Output used:

- Little things from the episcopal life. Images according to nature. German by Günter Dalitz . P. 260–425 in Eberhard Dieckmann (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. 4. The unbaptized priest. Stories. With a comment from the editor. 728 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1984 (1st edition)

literature

- Epilogue. From Rudolf Marx . P. 335–389 in Nikolai S. Leskow: At the end of the world and other stories. Dieterich'sche Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1968 (2nd edition)

Web links

- The text

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

Remarks

- ↑ Nikodim (* 1786) - secular name Nikolai Andrejewitsch Bystrizki - was bishop of Oryol (Russian Eparchy Oryol) from July 15, 1828 until his death on December 30, 1839 .

- ↑ Smaragd (1796–1863) - secular name Alexander Petrovich Kryschanowski - was Archbishop of Oryol from January 5, 1845 to June 5, 1858.

- ↑ Innokenti of Tauria (1800-1857) - secular name Ivan Alexejewitsch Borissow - was from March 1 to December 31, 1841 Bishop of Vologda (Russian Eparchy Vologda ).

- ↑ Warlaam (1801–1876) - secular name Wassili Iwanowitsch Uspenski - was bishop of Pensa from December 4, 1854 to April 22, 1860 (Russian Eparchy Pensa ).

- ↑ Ioann (* 1818) - secular name Wladimir Sergejewitsch Sokolow - was Bishop of Smolensk (Russian Eparchy Smolensk ) from November 13, 1866 until his death on March 17, 1869 .

- ↑ Porfiri (1804-1885) - secular name Konstantin Alexandrowitsch Uspenski - was bishop in Kiev from February 14, 1865 to December 31, 1877 (Russian Eparchy Kiev ).

- ↑ Filaret (* 1779) - secular name Fyodor Georgievich Amfiteatrow - was Metropolitan of Kiev from April 18, 1837 until his death on December 21, 1857 (Russian Eparchy Kiew ).

- ↑ Neofit (* 1794) - secular name Nikolai Petrovich Sosnin - was Bishop of Perm from March 29, 1851 until his death on July 5, 1868 (Russian Eparchy Perm ).

- ↑ Polikarp (* 1798) - secular name Feodossi Ivanovich Radkewitsch - was bishop of Oryol from July 12, 1858 until his death on August 22, 1867.

- ↑ Isidor - secular name Iakow Sergejewitsch Nikolski - was Metropolitan of Saint Petersburg from July 1st, 1860 until his death on September 7th, 1892.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian Очерк

- ↑ Russian Новости (news)

- ↑ Russian Исторический вестник

- ↑ Dieckmann on p. 703, 11. Zvo in the follow-up to the edition used

- ↑ Marx in the afterword of the 1968 Leskow edition, p. 380, 7th Zvu

- ^ Reissner, 1969 edition, p. 556, 10. Zvo

- ↑ Russian Nikodim (Bystrizki)

- ↑ Russian Smaragd Kryschanowski

- ↑ Russian Innokenti (Borissow)

- ↑ Russian Warlaam (Uspenski)

- ↑ Edition used, p. 299, 5th Zvu

- ↑ Russian Ioann (Vladimir Sergejewitsch Sokolow)

- ↑ Russian Porfiri (Uspensky)

- ↑ Russian Filaret (Amfiteatrow)

- ↑ Edition used, p. 334, 11. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 335, 16. Zvu

- ↑ Russian Neofit (Sosnin)

- ↑ Russian Polikarp (Radkewitsch)

- ↑ Edition used, p. 361, 21. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 424, 15. Zvo

- ↑ Russian Isidor (Nikolski)

- ↑ Edition used, p. 414, 11. Zvo to p. 420, 20. Zvo

- ↑ Russian Avgustin (Sakharov)

- ↑ Russian Grigori (Postnikow)

- ↑ Russian Filaret (Filaretow)

- ↑ Russian Makari (Bulgakow)

- ↑ Russian Arseni (Moskwin, Fjodor Pawlowitsch)

- ↑ Russian Filofei (Uspensky)

- ↑ Russian Mitrofan Voronezhsky

- ↑ Edition used, p. 304, 7. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 306, 18. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 306, 22. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 422, 16. Zvo

- ^ Reissner, 1969 edition, p. 755 middle

- ^ Reissner, 1969 edition, p. 556, 3rd Zvu