Koseki

A Koseki ( 戸 籍 ) is a family log book in Japan . It serves similar purposes as documents issued by the registry office in Central Europe and, since only Japanese can be registered, it is closely linked to the regulations on citizenship . It is a method of social control by the modern capitalist state. It differs from similar western registers in that the individual is not assumed as the basic unit, but the family belonging to a household serves as the basis; 戸 ko literally means "door."

The family register, which has been kept electronically since 1994, is not used for resident registration purposes, but rather for the fulfillment of civil registry tasks and is important for inheritance claims. In earlier times it also served as a criminal and military service register. This system is not to be confused with that of the population register ( jūminhyō ). Since the end of 1967 (Law No. 81), population and family registers have been compared.

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Already the laws of the Ritsuryō administration system, since the 8th century, contained provisions on (nobility) registers and household registers that were created as part of the six-year census. The registers at that time were called kogō-nen jaku and are first documented for the year 670.

From the late Heian period to the Edo period , it was taken up again with the goningumi-chō ( 五 人 組 帳 ), whereby not the individual household formed a unit, but the goningumi ("groups of five [of households]"). Its board of directors not only had to ensure the good behavior of the members, it was also responsible for the tax payments.

Mobility was and always remained strictly controlled and hardly took place in the 250 years of isolation, with a few approved exceptions. Rights and, above all, duties of the inhabitants (in the sense of the Neo-Confucian worldview ) arose from their membership of one of the four estates ( 身分 制 mibunsei ) or the outcasts ( 非人 hinin and 穢 多 eta ). That is why domestic workers etc. were also listed in the directory of an ie, which was also understood as an “economic community”. Registers of persons ( 宗 門 改 shūmon aratame ) were kept in the local Buddhist temples, which also certified that a person was not adherent to Christianity (which was banned until 1876). There were also tax registers, the kazai taichō. After the two were merged, it was called shūmon ninbenduchō.

Meiji era

A form of household certificates that only existed for a short time were the uji ko fuda issued in 1871-3, which proved a registration in the local Shinto shrine, which represented the new state religion.

With the emergence of the Japanese nation-state in 1868–73, primarily through the dissolution of the samurai domains ( 廃 藩 置 県 haihan chiken ), new registers of the ruled first had to be created, also for the previously excluded and the Ainu as well as for the violent incorporation of Okinawa in 1879 . After the introduction year 1872 one spoke of jinshin koseki. In this context, for the first time in Japanese history, all persons had to have both a family ( myōji ) and a first name. Which changes were notifiable was more precisely defined in 1878. In 1886 the format of the entries was standardized. Ainu registers were kept separately until 1933.

As part of the extensive civil law reform of the 1890s, a new family register law was passed in 1898. The registers now fell within the remit of the Justice Department. The registers do not necessarily have to be kept at the main residence, but at the “family seat” ( honseki ). The system of the head of the family ( setainushi ) was established. Provisions for marrying a woman who is the head of the household, the so-called nyūfu-konin, was regulated in Act No. 21 of 1898. In the Koseki , this is traditionally the oldest male descendant of the line. The Nationality Act of 1899 primarily implemented the principles of ius sanguinis in the form that was internationally common at the time, but also took into account the peculiarities of Japanese family law, which in turn were recorded in the Koseki . Japanese law requires all households ( 家 ie , also “bloodline”) to report births, deaths, marriages, divorces, but also criminal convictions to their local authorities, which incorporate this information into a detailed family tree that includes all family members under their jurisdiction . The above events are not officially recognized by the Japanese state if they are not registered in the Koseki . Only Japanese can be registered, there were and are therefore regulations that z. B. stipulated that a household head ( 戸 主 koshu ) must be Japanese or land ownership was only possible for them.

The Koseki Law was changed slightly in 1914.

Imperial house

The heavenly majesty ( Tennō ) and his other family do not have a Koseki, but are recorded in two other registers. On the one hand Emperor, Empress and Emperor's widow in Daitofu. On the other hand, for the extended family in Kōzokufu ( 皇 統 譜 ).

Colonies

The various family registers kept in the colonies were referred to as "outer", in contrast to those "inner" of the core realm. If a colonial subject lived there, an entry in the register there was possible.

Okinawa

The Ryūkyū Islands were regarded as a special administrative zone, but part of actual Japan, even after the king there was deposed in 1879. As early as 1873, the compilation of the Ryūkyūhan Koseki Sōkei had been initiated. This and the registers of immigrants remained incomplete and incorrect for a long time.

Bonin Islands

The handful of residents took their time to complete the registration in Koseki from 1875–81 . Since most of the residents were shipwrecked Europeans and their descendants (officially kika gaikokujin ), there were separate directories with names in Katakana .

Korea

Even under the Chosŏn dynasty , there were household head registers called hojŏk . They were used less to clarify family relationships, but to secure taxes and conscription.

The Japanese, who had been involved in the administration of Korea since 1905 , caused a law called Minseki-hō to be passed in March 1909 , which set up a register based on the Japanese model and was intended to replace the older ones. The conversion of the old directories went slowly and was not yet completed in 1945. In particular, illegitimate children, residents of peripheral provinces or people working in Manchuria were often not recorded. Because of numerous errors, this led to difficulties for many of those affected for a long time. After various additions, the Chosen koseki-rei was issued in 1921 . The regulations were designed in such a way that Koreans were barely able to get the "inner" status. The Japanese Citizenship Act of 1899 was never promulgated in Korea.

After the Pacific War

Reform 1947

The family registers have been kept since 1947 so that only two generations are listed in them. All those listed there have the same family name. Cross-references still allow you to trace a family history.

A new Citizenship Act ( Kokuseki-hō ) was promulgated on May 4, 1950 (No. 147 of 1950). The Ministry of Justice is responsible.

Since all family registers had been destroyed by the effects of the war , new registers were created in Okinawa, which remained under American military administration until 1972, by the Kōseki Seibi Hō of March 1, 1954.

The Honseki of the register for Japanese from Karafuto and the Bonin Islands was relocated to the rest of Germany, so that citizenship was retained for this group of people .

Through the "Special Law on Non-Returning Persons" of 1959, all Japanese (forcibly) staying behind on the Chinese mainland were declared dead, their entries were deleted from the registers and so thousands of zanryū koji were able to return to Japan after it had had diplomatic relations with again since 1972 China gave impossible.

Until 1968 the Koseki remained open to the public in justified cases. The Burakumin liberation movement achieved that in 1970 some details about the place of birth of people were deleted. In 1974, the Ministry of Health and Welfare forbade employers to have job applicants show them an extract from the register. In 1975 the names of the lineages of the individuals were deleted. Since 1976 it has been strictly confidential for non-official purposes. Originally the recording was made in extensive files, electronic recording began in 1994. Up until 2002 all of them were digitized and now only managed electronically. Anyone who appears on the Koseki (even if they have been deleted due to divorce or are no longer a Japanese citizen) are legally entitled to get a copy of the Koseki. This can be done in person in Japan or by post.

The Koseki replaces birth and death certificates , marriage certificates , etc. from other countries. However, the detailed information in the Koseki also makes it easy to discriminate against groups such as burakumin , illegitimate children (clearly recognizable until 2004) and single mothers. Lawyers get a copy of the Koseki if any of the listed people are involved in a legal dispute. To this day there are ID cards in Japan only for foreigners. Japanese are identified by their family register extract, nowadays with fingerprint and photo.

A typical Koseki has a page for the parents and the first two children, there are additional pages for other children. If a child marries, it usually falls out of the parents' Koseki and is listed in its own Koseki together with the spouse and their children. There are hardly any registered multigenerational households in which several families are grouped under one entry. Marriages with (non-registrable) foreigners are recorded in the Comments column ( mibun jikōran ).

Similar systems exist in China ( Hukou ), Vietnam ( Ho khau ) and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea ( Hojeok ). In South Korea, with the abolition of the Hoju system ( 戶主 制 , Hojuje ), the exclusively patriarchal family line, on January 1, 2008, the Hojeok was replaced by an individual family register.

Artificial fertilization

Children conceived through artificial insemination or sperm donation can easily be registered as wedlock, since the connection point is the woman who gave birth. However, this is not possible for widows who gave birth more than 300 days after the husband's death, e.g. B. when frozen sperm has been implanted. Such children are listed as illegitimate.

In cases of surrogate motherhood , which is only possible abroad, the Supreme Court has so far denied registration.

After gender reassignment

Since 2004 there has been the possibility that a gender reassignment, combined with a name change, can be registered with the consent of the family court. A new register entry will then be created for the person concerned.

Gay marriage

Japanese society has long been very tolerant of homosexual behavior . On the government side, it was not possible until 2019 to allow the possibility of a recognized same-sex partnership or marriage, which has become modern in many other developed countries since 2000. The entry of a “family” in which both partners have the same gender is therefore not possible in the Koseki.

Gay marriages between Japanese people legally concluded abroad have been recognized in their other legal consequences domestically since 2009. Individual municipal authorities, initially in Tokyo, began to issue “partnership certificates” in 2015.

Unregistered

The reporting requirements for the Koseki are not punishable by law. Especially in cases of illegitimate children and newly divorced marriages where it is not clear whether to register with the father or mother, people keep slipping through the system. Such unregistered persons ( mukosekisha ) then receive z. B. no passport in adulthood. Only since 2008 has there been an elaborate bureaucratic process to deal with the paperwork retrospectively.

See also

literature

- Chapman, David [ed.]; Japan's household registration system and citizenship: koseki, identification and documentation; London 2014 (Routledge); ISBN 9780415705448

- Endō Masataka [ 遠藤 正 敬 ]; State construction of 'Japaneseness': the Koseki registration system in Japan; Balwyn North, Victoria 2019 (Trans Pacific Press); ISBN 9781925608816 ; (Japanese orig .: 戸 籍 と 国籍 の 近 現代史 Koseki to kokuseki no kin-gendaishi , 2003)

- Tanaka Yasuhisa [ 田中康 久 ]; Nihon Kokuseki-hō Enkakushi; 戶籍 Koseki , 1982–84, 14-part series of articles

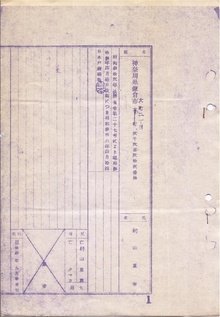

- 坂 本 斐 郎 [Sakamoto Ayao]; 外地 邦 人 在 留 外人 戶籍 寄 留 届 書 式 並 記載 例 [ Gaichi hōjin zairyū gaijin koseki kiryūtodoke shoshikinarabini kisairei ]; Tokyo 1938 (明倫 館)

- White, Linda; Gender and the Koseki in Contemporary Japan: Surname, Power, and Privilege; Milton 2018 (Routledge); ISBN 9781317201069

Individual evidence

- ↑ A first real resident registration law was the Kiryu-hō No. 27 of 1914, followed by the Jūmin Toroku hō (No. 218 of 1951). Until 2012, there were separate foreigner population registers.

- ↑ Ritsuryō State (published 2020-02-03)

- ↑ See Lewin, Bruno; Aya and Hata: People of ancient Japan of continental origin; Wiesbaden 1962 (Harrassowitz)

- ↑ Martin Schwind : The Japanese island kingdom . tape 2 - cultural landscape, economic superpower in a small area. de Gruyter, Berlin 1981, ISBN 3-11-008319-1 , Chapter 3: Man and Landscape during the Tokugawa Period, p. 137, 142 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ according to the Dajōkan Edict, No. 322 of 1871.

- ^ Instructions from the Ministry of the Interior, May 27, 1878.

- ↑ Ordinance of the Ministry of the Interior, No. 22 of October 16.

- ↑ suction. Ainu ninbetsuchō since 1873; preserved in the Hokkaido Reclamation Museum ( Hokkaidō kaitaku kinenkan ). Consolidation according to Imperial Edict no. 37 of 1932. In Karafuto there were from 1909 Karafuto dojin Toguchi kisoku and for 1926 Otasu resettled Oroken and nivkh people the genjūmin jinmeibo.

- ↑ Regarding various business activities, there were reservations in various laws, such as B. Ownership of Japanese ships and (shares in) shipping companies, operation of pawn shops, banks (ownership of shares in semi-governmental, including Yokohama Specie Bank , Chōsen Ginkō ), insurance companies (Law 69, 1900, in conjunction with Imperial Edict 380, 1900), Mining, commercial fishing and professional practice as a doctor, pharmacist, civil servant, lawyer etc. pp. Many of these restrictions still apply today, albeit on a changed legal basis.

- ↑ Special Ordinance No. 51 of July 29, 1896.

- ↑ In force in 1922. The almighty Governor General of Korea adopted Japanese laws as he saw fit by ordinance as seirei.

- ↑ Law No. 224 of 1947.

- ↑ What is at least doubtful for the time of the US administration of the Bonin Islands, 1945-68, cf. Chapman, David; Different Faces, Different Spaces: Identifying the Islanders of Ogasawara; Social Science Japan Journal, Vol. 14 (2011), No. 2, pp. 189-212.

- ↑ Mikikansha tokubetsu sochihō

- ^ New law takes on patriarchal family system. (No longer available online.) Korea Women's Development Institute, June 7, 2007, archived from the original on September 19, 2012 ; accessed on February 4, 2009 .

- ↑ In the Mukai / Takada 2007 case. The situation is even more complicated for Baby Manji .

- ↑ Law No. 111 of July 16, 2003, in force July 2004.