Force Dynamics (Semantics)

The force dynamics , English force-dynamics or force-dynamics model in the language is part of a higher-level concept for space and process semantics (see also spatial relation ). The concept was largely inspired by the US linguist Leonard Talmy in the early 1980s. Talmy began to develop his theoretical considerations as early as 1975 while dealing with the theoretical conceptions of generative semantics . His idea was to include the concepts of cognitive psychology and the cognitive grammar , founded in particular by Ronald Langacker , in a branch of cognitive linguistics in the theoretical-linguistic considerations. Langacker's theoretical concepts are shaped by the assumptions of Gestalt psychology . Other influences go back to Brennenstuhl (1975), a PhD student at Berkeley University, and Ray Jackendoff .

Talmy assumes four systems of ideas , the imaging systems , which would be used in natural languages . They are independent of each other and thus their effect can be added, they are:

- the geometric configuration;

- the specification of the perspective point, the location of the “spiritual eye”, mindsight ;

- the focus of attention and in particular;

- the force dynamics, force dynamics .

According to Talmy, the following semantic components occur in a movement event :

- motion (motion) as an expression of movement, as the fact of movement,

- figure as an expression of the moving object,

- ground , as an expression of the background in front of which movement takes place,

- path as an expression of the direction or the path that the figure (object) takes with respect to a background.

In addition, two further components can occur in a co-event:

- manner (manner) as an expression for the manner of movement,

- cause as an expression for the cause or who caused the movement.

While the motion or movement is realized exclusively with the verb, the path or way can be lexicalized either in the verb ( verb-framed language ) or outside the verb (satellite-framed languages).

Force dynamic concept

Talmy developed the theory of force dynamics in language. He assumes that a kind of "causal force" plays a role in the cognitive processing of everyday language conceptualizations, which then lead to the linguistic utterance.

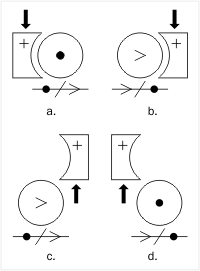

For Talmy, verbalization or expressions can have a force-dynamic pattern or they can be force-dynamic neutral. A basic characteristic of a force-dynamic expression is the presence of two "force-effective" elements. Languages differentiate between these two forces based on their roles. The force that is in focus is called the agonist and the force that is directed against it is called the antagonist. In the door example, the agonist is the opening and the force that prevents the door from opening is the antagonist. A third relevant factor is the imagined balance or imbalance between the two forces. The forces are by definition out of balance when the two forces are equally strong. But if one force is stronger or weaker than the other, the stronger force is marked with a plus sign and the weaker force with a minus sign. In the example, the antagonist is stronger because he is actually holding the door closed.

A sentence like “The door is closed” is force-dynamic neutral because there are no forces opposing each other. The sentence “The door cannot be opened”, on the other hand, shows a force-dynamic pattern. Because there is apparently something here that counteracts the tendency, option of the door to open. There is another force that is preventing it from opening or being opened.

Force effects have an intrinsic tendency to force, either to act or to rest. For the agonist, this tendency is indicated schematically with an arrowhead (action) or with a large point (rest). Since the antagonist, by definition, has an opposite tendency, it does not need to be marked. In the example of the door, it has a tendency to act.

The result of a presented force-dynamic scenario depends both on the intrinsic tendency and on the idea of the balance between the forces. The result is shown schematically by a line under agonists and antagonists. The line has an arrowhead when the result is action and a large dot when the result is resting. In the example, the door remains closed. The antagonist succeeds in preventing the door from being opened. The sentence "The door cannot be opened" can be represented force-dynamically by a diagram.

With these basic concepts, generalizations of spoken sentences can in principle be represented. The force dynamic situations in which the agonist is stronger are expressed in sentences like "X happened despite Y", while situations in which the antagonist is stronger are expressed in the form of "X happened because of Y".

Agonist

The human imagination operating with the term “agonist” assigns an activity inherent to it that corresponds to an intrinsic tendency, which is what an agonist would do if the antagonist did not act on it. In the force-dynamics model of verbalization, the interacting entities are not necessarily interpreted according to, for example, scientific , physical, etc. conditions. The entity selected in the imagination is connected to another entity in such a way that it could influence the first one. - Examples:

Die Vase fiel vom Schrank. Das Haus versank im Boden.

From the point of view of scientific observation , investigation , experiment , interpretation and the formation of models or theories, every event , every entity would be preceded by a regular occurrence or would be included in it. Pinker (2014) also describes the interpretations in the force-dynamics model as "intuitive physics" and contrasts them with "scientific physics".

literature

- Force Dynamics in Language and Cognition. In: Cognitive Science. 12, 1968, pp. 49-100. (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- Steven Pinker : The stuff that thinking is made of. What language reveals about our nature. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2014, ISBN 978-3-10-061605-0 .

Web links

- Leonard Talmy's website with résumé and publications

- Hans Ulrich Fuchs: Structures of figurative language. Lecture 1 on metaphors in nature and technology. ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences (home.zhaw.ch)

- Hans Ulrich Fuchs: Shaping Force-Dynamic Gestalts in Natural Sciences. Lecture 2 on metaphors in nature and technology. ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences (home.zhaw.ch)

- Hans Ulrich Fuchs: From figurative language to formal thinking in the natural sciences. Lecture 3 on metaphors in nature and technology. ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences (home.zhaw.ch)

Individual evidence

- ^ Leonard Talmy: Figure and Ground in Complex Sentences. In: Proceedings of the First Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 1975, pp. 419-430. (journals.linguisticsociety.org)

- ↑ Wolfgang Wildgen: Cognitive grammar: classic paradigms and new perspectives. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019600-9 , p. 91 f.

- ↑ Waltraud Brennenstuhl : Theory of action and logic of action: Preparations for the development of a language-adequate logic of action. Scriptor-Verlag, Kronberg (Taunus) 1975.

- ↑ Ulrike Schröder: Communication-theoretical issues in cognitive metaphor research: a consideration from its beginnings to the present. (= Tübingen Contributions to Linguistics. Volume 539). Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2012, ISBN 978-3-8233-6777-2 , p. 26.

- ↑ Wolfgang Wildgen: Cognitive grammar: classic paradigms and new perspectives. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019600-9 , p. 104 f.

- ↑ Steven Pinker: The Stuff Thought Is Made Of : What Language Reveals About Our Nature. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2014, ISBN 978-3-10-061605-0 , p. 278.