Mamuralia

In the Roman religion , the Mamuralia were a festival that, according to the Philocalus calendar, was celebrated on the 14th, according to John Lydos on the Iden, that is, on the 15th of March, but is only known from late antique sources. Presumably, the celebrations began at noon on the 14th and lasted until noon on March 15th. Between the feast of the navigium Isidis on March 5th and the Liberalia on March 17th, the Menelogia rustica also list a sacrum Mamurio, a sacrifice to Mamurius, which is related to the Mamuralia, whose name only Philocalus has handed down.

The Mamuralia are associated with the god Mars and are said to have received their name in honor of Mamurius Veturius , a legendary blacksmith at the time of the Roman king Numa Pompilius . Mamurius is said to have made eleven copies of the holy shield ( ancile ) that floated down from heaven . As a reward, his name was added to the carmen Saliare .

From this only fragmentary cult song of the Salier priesthood, Varro passed on the words Salii quod cantant mamuri veturi ("and the Salians sang mamuri veturi "), which, following his attempt to explain, meant memoriam veterem ("old memory"). Varro did not know any Mamurius Veturius, which is also true of other historians and poets of the time. Neither Titus Livius nor Virgil mention his name. Only with Dionysius of Halicarnassus is the person introduced who shortly thereafter also mentions Ovid in his Fasti , while the festival itself was unknown to him. The elegiac Properz credits him with the creation of a bronze statue of the god Vertumnus as a further work . The introduction of the festival will therefore probably not have taken place until the imperial era .

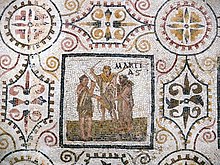

According to Johannes Lydos, the Salians came into action on this day and performed their weapons dance, in which a man dressed in fur, representing the ancilia blacksmith, was ritually beaten out of the city with sticks, symbolically driving out winter. But this seems to have been the late invention or the embellishment of a ritual which, according to Minucius Felix and Servius , consisted in the fact that on a day dedicated to Mamurius, branches were struck by branches in imitation of hammer blows. This scene is shown on the monthly mosaics from El Djem for the month of March made at the end of the 2nd or the beginning of the 3rd century .

literature

- Jan N. Bremmer : Three Roman Aetiological Myths. In: Fritz Graf (ed.): Myth in a society without myths: The paradigm of Rome (= Colloquium Rauricum. Volume 3). Teubner, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1993, pp. 158-174, here: pp. 160-165.

- Gerhard Radke : Roman festivals in March. In: Tyche. Contributions to ancient history, papyrology and epigraphy. Volume 8, 1993, pp. 129-142, here: pp. 133-134.

- Hermann Usener : Italian Myths. In: Hermann Usener: Small writings. Volume 4: Works on the history of religion. Teubner, Leipzig et al. 1913, pp. 93–143, here pp. 122–126.

Individual evidence

- ↑ CIL I² 260.

- ^ Johannes Lydos, De mensibus 4.49 (106 W).

- ^ So Gerhard Radke: Roman festivals in March. In: Tyche. Contributions to ancient history, papyrology and epigraphy . Volume 8, 1993, pp. 129-142, here p. 133.

- ↑ CIL I² 280.

- ↑ Plutarch , Numa 13.

- ↑ Varro, de lingua Latina 6.49.

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus 2.71.

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti 3, 383-392.

- ↑ Properz 4,2,61.

- ↑ So Jörg Rüpke : Time and Festival. A cultural history of the calendar. CH Beck, Munich 2006, p. 104, similar to Jan N. Bremmer: Three Roman Aetiological Myths. In: Fritz Graf (ed.): Myth in a society without myths: The paradigm of Rome (= Colloquium Rauricum. Volume 3). Teubner, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1993, pp. 158-174, here: pp. 160-165.

- ↑ Minucius Felix, Octavius 24; Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 7,188.