Nakago

As Nakago ( Japanese 茎 , also 中心 or 中子 ) the Erl is referred to in Japanese blade weapons (such as Katana , Tachi , Tantō , Tsurugi , Nagamaki and Naginata ).

Description and use

The nakago is primarily used to attach the sword handle ( tsuka ) to the blade. It is provided with one hole in historical models and two holes in newer models. A pin made of wood or bamboo ( 目 釘 , Mekugi ) - rarely made of metal - is driven through the holes to secure the handle to the fishing rod. On the Nakago there is usually the engraved signature of the blacksmith ( 銘 , mei , dt. "Signature") and, if necessary, further information such as date, occasion and client. If a signature is missing, this is referred to as mumei ( 無 銘 , German "without signature"). A forged signature or a signature added later by someone else is called gimei ( 偽 銘 , dt. " Forged signature"). There are different forms of fishing rod and fishing point ( Nakago-Jiri ), which are named below and shown below.

Fishing shapes

A distinction is made between the following types of fishing:

- Kijimomo-Gata ( 雉 子 股 形 , "pheasant feet "): Often used with the Tachi swords.

- Furisode-Gata: ( 振 袖 形 ): Named after the long sleeves on the kimono of Japanese women, this form is only found on Tantō of the Kamakura period .

- Tanagobara-Gata ( 鱮 腹 形 , for " Tanago belly"): This type of hinge is found on the swords of the Muramasa school, the Heianjo Nagayoshi school and the Shitahara school in the Muromachi period

- Shiribari-Gata or Sotoba-Gata ( 卒 塔 婆 形 ): Another word for stupa that can be found on the tombs of Buddhist believers. Attributed to the Kongōbei school in the Muromachi period .

- Futsu

- Fune-Gata or Funa-Gata ( 船形 , "boat shape"): This hinge shape is associated with the swordsmith Masamune from Sōshū and his school.

- Gohei-Gata ( 御 幣 形 ): Modeled on the cut sheets of paper ( Gohei ) in Japanese temples. Each side of the tang has an equal number of these step-shaped indentations on the narrow side of the tang. This form is attributed to Iso Kami Kunitero in the Edo period .

Shapes of fishing tips

The shapes of the fishing tips ( 茎 尻 , Nakago-Jiri ) are named as follows:

- Kuri-Jiri ( 栗 尻 , "chestnut end"): rounded tip

- Haagari ( 刃 上 ((が) り) , "raised blade") also Haagari-kurijiri ( 刃 上 ((が) り) 栗 尻 , "chestnut end with raised blade"): asymmetrically rounded tip

- Kiri ( 切 り , "cut off") or Ichimonji ( 一 文字 ): tip cut off in a square

- Kengyō ( 剣 形 , "sword shape"): symmetrical tip

- Iriyama-gata ( 入 山形 ) or Katayama-gata ( 片 山形 ): asymmetrical tip

Another form is called Kiri Nakago-Jiri . This shape only occurs with cut, i.e. shortened ( suriage ) blades. This shortening happened when an old, thinly ground or broken blade was reworked into a dagger ( Tantō ) or a short sword ( Wakizashi ). In order to adapt the handle length to the respective shorter dimension, the sword tang was simply shortened to the required length.

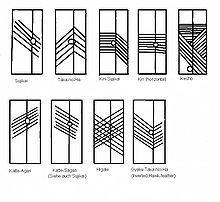

For file marks

Typical "scratches" can be seen on the tang, which originate from working the tang with a file. These traces of processing are called Yasurime ( 鑢 目 ). Machining marks with a hammer, on the other hand, are called tsuchime ( 槌 目 ). They are used as a kind of second signature of the blacksmith who made the sword. These are also named:

- Sujikai ( 筋 違 )

- Takanoha ( 鷹 (の) 羽 )

- Kata-Sujikai ( 片 筋 違 ) or Kiri-Sujikai ( 切 筋 違 )

- Kiri ( 切 (り) ; horizontal)

- Keshō ( 化粧 )

- Katte agari ( 勝 手上 ((が) り) )

- Katte-Sagari ( 勝 手下 ((が) り) ; see also Sujikai)

- Higaki ( 檜 垣 )

- Gyaku-Takanoha ( 逆 鷹 (の) 羽 )

- Sensuki ( 鏟 鋤 )

- Ō-Sujikai ( 大 筋 違 )

- Saka-Takanoha ( 逆 鷹 (の) 羽 )

- Katte-Sagari in Shinogiji, Kiri in Hiraji

- Kiri in Shinogiji, Katte-Sagari in Hiraji

- Keshō-Yasuri ( 化粧 鑢 )

Types of Nakago after the cut

The classification of types of Nakago according to the abbreviation is used exclusively for abbreviated Japanese blades. The state of the nakago is described as Japanese blades were often shortened to be used as tantō or wakizashi . The shortening is mostly used to keep old blades back in use. The blades are never shortened at the point ( kissaki ) unless the kissaki is damaged or broken. The following classifications are used to differentiate:

- Ubu nakago

- Denotes a Nakago that is new and completely unchanged since it was manufactured. In some cases the bend of the nakago is changed or additional mounting holes for mekugi (retaining pins) have been drilled. As long as the blade or the bend of the Nakago has only been changed very slightly, the Nakago will still count as Ubu nakago .

- Suriage nakago

- Denotes an "abbreviated" Nakago. The nakago is slightly shortened. As a result, the Hamachi (the side of the Nakago that lies on the cutting edge) and the Munemachi (the side of the Nakago that lies on the back of the blade) continue to run towards the place (Boshi). The nakago is called the suriage nakago when the mei (blade signature) is still completely preserved.

- O-suriage nakago

- A heavily shortened nakago. In contrast to the Suriage nakago , in which the Nakago was only reshaped, the O-soriage nakago is formed from a part of the actual blade. The mei (signature) is lost as a whole, but can be preserved as an Orikaeshi-Mei or as a Gaku-mei .

- Orikaeshi-mei

- The metal piece on which the Mei is engraved is attached to the Nakago and bent to the opposite side. This makes the Mei appear upside down.

- Gaku-mei

- The metal piece on which the Mei is engraved is cut out in a rectangular shape and then attached to the modified Nakago.

- Machi-okuri

- The Ha-Watari (transition point from the cutting edge to the Nakago) is shortened towards the location by moving the Munemachi and Hamachi to the blade tip by grinding around without actually shortening the Nakago. This does not make the blade shorter as a whole. In some cases, however, the Nakago is shortened without moving the Munemachi and Hamachi,

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kōkan Nagayama: The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords. Verlag Kodansha International, 1998, ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0 , p. 71 ff.

- ↑ Kōkan Nagayama, The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords , Kodansha International, 1998, ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0 , p. 67.

- ↑ Kōkan Nagayama: The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords. Kodansha International, 1998, ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0 , p. 68.

- ↑ Kōkan Nagayama: The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords. Kodansha International, 1998, ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0 , p. 69.

- ↑ 各部 の つ く り と 見 ど こ ろ. 財 団 法人 日本 美術 刀 剣 保存 協会, Retrieved May 14, 2010 (Japanese).

- ↑ Kōkan Nagayama: The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords. Kodansha International, 1998, ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0 , p. 66.

literature

- Kanzan Satō, Joe Earle: The Japanese sword. Volume 12 from the Japanese arts library. Kodansha International Publishing House, 1983, ISBN 978-0-87011-562-2 .

- John M. Yumoto: The Samurai Sword. A manual. Ordonnanz-Verlag, 1989, ISBN 978-3-931-42500-5 .

- Kōkan Nagayama: The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords. Kodansha International Publishers, 1998, ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0 .

- Nobuo Ogasawara: Japanese swords. Hoikusha Publishing House, 1993, ISBN 978-4-586-54022-8 .

- Clive Sinclaire: Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Press, 2004, ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8 .

- Victor Harris: Cutting Edge: Japanese Swords in the British Museum. Tuttle Pub., 2005, ISBN 978-0-8048-3680-7 .