Katana

The katana [ ka.ta.na ] is the Japanese long sword (Daitō) . In today's Japanese , the term is also used as a general term for sword . Weapons made today are also called shinken , "real swords".

The word katana is the kun reading of the Kanji 刀 , the on reading is tō , from Chinese Dao . It denotes a certain curved sword shape with a single edge. The counterpart are the double-edged Tsurugi (also called Ken ).

The shape of the blade is similar to that of a saber , but the handle ( tang ) - called nakago in Japanese - is not bent towards the edge as is often the case with a classic saber. The biggest difference is in the handling. While the katana is usually wielded with two hands, the average saber is designed as a one-handed weapon. This difference leads to a different style of fencing.

Development history

The katana emerged from the Tachi 太 刀 (long sword) in the 15th century and was traditionally used by Japanese samurai from the end of the 14th century (early Muromachi period ) , especially in combination ( Daishō 大小 , large-small ) with the short wakizashi 脇 指 ( shōtō 小刀 , short sword ). It is very similar to the earlier Chinese Miao Dao and the swords of the northern Japanese Ainu . A real Japanese blade makes the hardness zone ( Hamon 刃 文 ) created by special forging or hardening techniques and (in Koshirae 拵 え ) that is usually covered with ray skin or shark skin (false ray skin) ( samegawa 鮫 皮 ) and mostly artfully wrapped with silk ribbon unmistakable Handle ( tsuka 柄 ). However, handle wraps made of leather were sometimes used. Carved hardwood or ivory handles were only available for decorative or presentation swords. A katana blade is usually made of at least two different types of steel , one ductile for the core and one hard for the cutting edge. Both components were first “refined” individually by folding and welding them several times before they were forged together to form a blade.

The katana in the narrower sense is a one-and-a-half-handed sword bent towards the back with a blade over two shaku 尺 in length (that is about 60.6 cm) and a handle of different lengths. It weighs around 900 to 1400 grams. A blade with less than two Shaku is a one-handed wakizashi (or Shōtō = short sword) and one with less than one Shaku is a combat knife ( Tantō , Aikuchi , Hamidashi). The scabbards of all three types of sword are called Saya 鞘 and are made of lacquered wood. Only the mass-produced military swords of the 20th century were delivered with tin sheaths, which, however, had a wooden lining.

In Japan, other swords were also used, e.g. B. a longer and heavier version of the katana, the dōtanuki . This is known from the television series Lone Wolf & Cub , as well as the film Okami - The Sword of Vengeance . It was also preferred by Katō Kiyomasa , a general of Toyotomi Hideyoshi .

The swords or the blades are assigned to different periods → Nihontō . Katanas are also differentiated according to the five classic swordsmithing traditions Gokaden .

Carrying the gun

Katana and Wakizashi were always carried with the edge up through the obi (belt). This is a "civilian" way of wearing that became established when, after the end of the Japanese wars in the early 17th century, wearing armor was no longer part of everyday life for the samurai. When entering a house, the katana was released from the obi and, if hostilities were to be feared, it was carried back with the handle in the left hand or in the right hand as a sign of confidence. When seated, the katana was within easy reach on the floor, while the wakizashi often rested on the hip. On the street the swords were wielded in a suitable outfit (koshirae), which included a lacquered sword scabbard (saya) . When not in use immediately, the blade was kept in the own house in the shirasaya , which protected the steel from corrosion thanks to a particularly close fit and the untreated magnolia wood. Nowadays, so-called Shirasaya katanas are also often offered, the entire outfit of which is made of untreated wood. This inconspicuous outfit without a tsuba or other decoration was often used towards the end of the 19th century after the imperial ban on sword weapons, because the Shirasaya outfit resembled a bokutō , i.e. a wooden sword. In later times (until the 20th century) there was hidden blades similar to Stockdegen of the West; a (short) sword blade was often hidden in a mount that looked like a walking stick made of bamboo or like a stick cut from a branch.

Up until the early Muromachi period (i.e. the late 14th century), armor included the tachi . From this point on, the Tachi, carried with the cutting edge down on a weir hanger, were increasingly replaced by katanas . These had a textile (silk) tape ( Sageo ) to secure them , with which the Saya could be attached to the Obi. For Tachi one usually wore a typical combat knife ( tanto ), the katana was the Wakizashi added.

The production

There are many steps involved in making a katana. The production of such a sword takes several days to weeks. First, broken pieces of the Tamahagane steel obtained in a kind of racing furnace (Tatara) are folded into a block and doused with mud and ashes. This ensures that contaminants combine with it and are thus released from the steel. Then the whole thing is heated to welding temperature (warm white) in order to join the fragments of the Tamahagane by fire welding . After this process, the Tamahagane block is folded up to 15 times so that the carbon is evenly distributed. This later ensures that the blade is evenly hard. After this process, up to 32,768 layers of steel lie on top of each other. A softer steel is now forged into the hard Tamahagane block, otherwise the blade would break under load (other techniques are also available). Now the block is forged in length by hand for days and shaped into a blade. The shape of the blade is refined with a special scraper (SEN).

In the next step, hardening , the sword is first provided with a layer of clay using a fine bamboo spatula . This is applied thinner on the cutting edge than on the rest of the blade and this in a pattern that is typical for the respective blacksmith . After drying, the blade is brought to hardening temperature (about 800 ° C) in a charcoal fire and quickly cooled in warm water. This solidifies the structure of the steel, and martensite , a particularly hard steel modification, is formed. The cutting edge is cooled faster by the hardening process and therefore becomes harder, while the blade body remains softer and more elastic. This process shows up as a hamon , a kind of pattern in the cutting edge. This is a more or less clearly defined area of the cutting edge, a result of what is known as differential hardening.

Then the blade is filed over again and, if necessary, provided with a signature ( Mei ), which is hammered into the tang ( Nakago ) with a small chisel . After this treatment the grinder (togishi) receives the sword. In around 120 hours it gives the surface of a katana the incomparable appearance, but also the necessary sharpness . Some blades are then given a decoration ( horimono ) by the engraver , which is incorporated with small chisels. Other specialized craftsmen make the handle (tsuka) , the scabbard (saya) and the metal fittings (kodogu) .

The Steel

Japanese sword blades are traditionally made from tamahagane . They are manufactured in an almost unique way in a sophisticated process. The reason for this production method lies in the iron sand used , which has been cleaned of impurities at high temperatures in order to produce purer iron. The steel was extracted from local iron sand in a Tatara (a rectangular racing furnace ). At first it was still inhomogeneous and had an uneven carbon content of around 0.6–1.5% (Tamahagane). For the blade, however, you need steel with a uniform carbon content of around 0.6–0.7%. In order to remove all impurities and to control and evenly distribute the carbon content of the blade, a special folding technique was developed that was very effective, but also labor-intensive. A special feature of the iron sands is their sulfur and phosphorus poverty. These elements are undesirable in steel because they lead to segregation (considerable disturbances in the steel structure). Therefore, low-sulfur charcoal is also used in forging.

First, the steel is forged from smaller fragments into an ingot, which is then repeatedly heated, alternately folded across and lengthways and then forged again.

During forging , there is a significant loss of material due to scaling of the steel, at the same time the carbon content is also reduced due to oxidation . In order to compensate for the loss and to control the carbon content, steel bars with different carbon contents are connected to one another in the course of forging. Further folding and forging results in the numerous wafer-thin "layers" of steel, which can be made visible on the blade surface using special grinding and polishing techniques ( Hada ).

This forging process is used exclusively to clean and homogenize the steel and to control the carbon content ( refined steel ). The view that a good katana should be forged from as many layers as possible is based on a misunderstanding. Depending on the quality of the Tamahagane and the desired carbon content, the ingot is forged around 10 to 20 times. A tenfold simple fold results in 1024 layers; if the steel is forged 20 times, more than a million layers are created. The blacksmith only continued this process until he got a perfectly uniform ingot with the desired properties. Unnecessary forging only made the steel softer and would have led to further loss of material through burn-off.

In machine-made katanas from World War II ( Guntō ), the steel typically consisted of 95.22% to 98.12% iron and had a carbon content of over 1.0%. This made the steel very hard. In addition, it contained a variable amount of silicon , which gave the blade greater flexibility and resistance. Depending on the origin of the raw material, copper , manganese , tungsten , molybdenum and (unintentional) traces of titanium were also present in the blade material in small quantities .

Not all steel is suitable for swords. In contrast to cheap copies, a forged original is not made of 440 A stainless steel (1.4110) → knife steel . This is a specially developed knife steel which, as rolled steel with a Rockwell hardness of up to 56 HRC, is not suitable for the production of sword blades. In addition, an original does not have a serrated edge , engraving or etching that is supposed to imitate a hamon . A real hardening zone can only be achieved through a special treatment of the steel (see: Martensite ). The hardening of the cutting edge area to up to 62 HRC makes the special quality of the Japanese blades together with the given elasticity . The high hardness of 60–62 HRC also ensures that the sharpness is maintained for a long time ( edge retention ). The reason for the superior cutting performance in the pressure cut (the opposite is the pull cut with the blade moving back and forth like with saws ), which is also important when shaving and runs strictly linearly at right angles to the cutting edge, is the fine iron carbide , which is a very thin cutting edge without breakouts caused by the sharpening grinding. This fine iron carbide is mainly found in rusting steels, stainless high-tech steels cannot reach the fine, microscopically scratch-free cutting edge, but they are excellent at drawing cuts due to the microscopically fine nicks and chippings that work like a microsaw. In the early Middle Ages , steel blades were artfully folded by the Vikings ; there were very attractive damascene blades that were never available in this form in Japan. The Franks also made good steel, and the blades made from it could do without the folding of the steel and the homogenization achieved with it. The Japanese steel products could not be compared to European blades in terms of the manufacturing process and the properties achieved, as well as in terms of surface treatment, because they served a completely different war technique and because armaments in Japan developed completely differently from European ones.

The construction

The swordsmith has always faced the task of creating a weapon that is both sharp and resilient - the sword must not become blunt, rust or break quickly. Depending on the carbon content of the steel and the hardening process, it can produce a blade that is rich in martensite and therefore very hard and sharp, but also brittle and fragile. In contrast, if a more ductile steel is used, the blade will dull faster.

With the katana, this conflict of goals is resolved by a sandwich construction . The prevailing technique embeds a core made of ductile , somewhat softer, lower-carbon steel in a jacket made of harder, high-carbon steel: the blacksmith folds a long, narrow bar made of "high carbon steel" in a U-shape lengthways and welds a matching bar in the fire " Mild steel ”. This combined bar is forged into the raw blade in such a way that the closed side of the "U" becomes the cutting edge of the blade. The combined bar is no longer folded.

Conversely, other constructions can, for example, embed the hard blade steel in a “U” made of mild steel, or the blacksmith combines hard blade steel and soft back steel with two side layers of medium-hard steel. There are a number of more complex techniques that do not necessarily result in better blades, but rather were often introduced by weaker blacksmiths in order to circumvent the difficulties of the difficult hardening process.

Very short blades were also sometimes made from a single steel (mono material).

Larger blades make a more complex construction necessary.

- Maru The cheapest of all constructions occasionally used for Tantō or Ko-Wakizashi; these simple blades have not been differentially hardened. The blade is made from a single type of steel.

- Kobuse A simpler blade construction, which was often used in major military conflicts with high material requirements up to the Second World War due to the cheaper production.

- Honsanmai The most common construction for blades. With it, the side surfaces of the blade are protected by the “hard steel”, which makes the blade robust and has the advantage that the back of the blade (which could also be used to parry) is not hardened. This prevented the blade from breaking. Some old blades still show these traces of a fight today.

- Shihozume A construction that is similar to the Honsanmai, except that the back of the blade is protected by a hard iron cord.

- Makuri A simpler construction in which a soft iron core is completely surrounded by a hard steel body.

- Wariha Tetsu Simple construction but very flexible.

- Orikaeshi Sanmai A slightly modified form of the Honsanmai construction.

- Gomai A somewhat unusual variant with a hard iron core followed by a layer of soft iron. Finally, the construction is surrounded by a layer of hard steel.

- Soshu Kitae One of the most complex constructions with seven steel layers. This construction was used by the blacksmith Masamune and is considered a masterful work.

The hardening

Similar to western swordsmiths of the Middle Ages, who used differential hardening, Japanese blacksmiths do not harden the blade evenly, but differently. The blade is often forged almost straight and is given the typical curvature through hardening, with the blade edge having a hardness of about 60 Rockwell , but the back of the blade only a hardness of about 40 Rockwell. The hardening is based on the change in the lattice structure of the steel, austenite is converted into martensite , which has a higher volume, as a result of the quenching caused by the temperature gradient in the hardening bath (traditionally in a water bath) . So the blade expands and curves at the cutting edge. The curved blade has the advantage that it cuts better and makes the cut more effective, which is why it has become established over time.

Before hardening, the blade is coated with a mixture of clay mud, charcoal powder and other ingredients. This layer is much thinner on the edge than on the rest of the blade. For hardening, the blacksmith also heats the cutting edge more than the back of the sword, whereby it is essential that despite this heat gradient (for example 750-850 ° C) in the cross section, the cutting edge and the back of the blade are heated evenly along the length. When quenching in warm water, the hotter cutting edge (Ha) cools down faster and forms a higher proportion of hard martensite than the rest of the blade. The delimitation of this narrow zone can be clearly seen after hardening and polishing the blade (Hamon). It is not a defined line, but a more or less wide zone.

Some blacksmiths make the hardness zone of the cutting edge livelier by making the clay coating wavy, irregular or with narrow transverse lines before it dries. The resulting shapes of the hamon can be an indication of the blacksmithing school, but are usually not a sign of a certain quality. There are very high-quality blades with straight hamons that are as narrow as a millimeter, and there are shapes with very large waves that are not regarded as subtle (and vice versa). A hamon with many, very narrow "waves" can produce narrow, more elastic zones ( Ashi , "feet") in the cutting edge, which can prevent a crack in the cutting edge from continuing. However, a blade with a transverse crack is generally unusable for use.

By varying the duration and temperature of the heating before quenching, the blacksmith can achieve further effects on the surface of the sword (for example Nie and Nioi - cloud-like martensite formations with different particle sizes, which also agglomerate and thus show different structures).

The hardening process (austenitizing and quenching) can be followed by tempering , in which the hardened blade is heated to around 200 ° C in the embers or on a copper block previously heated to red heat, which relaxes the hardening structure (the martensite). This gives the blade a unique combination of hardness and toughness.

The quenching (hardening and tempering) is a step of difficult in the production of the Katanas that can fail even an experienced forger. In this case the blade can be hardened and tempered again. This can only be repeated a few times and if these rescue attempts have failed, the blade is discarded.

The combination of a hard cutting edge with an elastic blade core gives the katana's blade an enormous toughness with lasting sharpness.

The polishing

After the blacksmith has finished his work, which includes an initial surface treatment with the Sen , a kind of metal scraper, he hands the sword over to a polisher, known as a Togishi . Its task is to grind and polish the blade first with coarse stones and later with finer stones in a process that takes around 120 hours . The Togishi not only sharpens the blade, but also allows the superficial steel structures to come into their own with different techniques, i.e. the hamon and the hada , the “skin” that gives an insight into the forging technique . Even small mistakes can sometimes be concealed.

More than the technical aspect of Japanese blades, the high quality of the steel and the aesthetic properties are valued and admired today, which, however, only come to light through a well-crafted polish. This means that the shape and geometry of the blade, as designed by the blacksmith, are precisely preserved. Therefore, the craft of the foreman includes a very precise knowledge of the forging styles of the individual blacksmiths and blacksmith schools of past centuries.

Inexperienced hands can irreversibly spoil a blade through incorrect grinding / polishing.

Form

The differently pronounced curvature (sori) of the katanas is intentional; it was created in a development process that lasted over a thousand years (of course also parallel to the armor of the samurai) and varied constantly until it finally represented a perfect extension of the slightly bent arm. It also results in part from the heat treatment used: With differentiated hardening, the cutting part of the sword expands more than the back.

Many modifications are possible within the basic pattern of the katana , some of which depend on the preferences of the blacksmith and his customers, and partly on the tradition of the respective sword school. The geometry of the blade ( tsukurikomi ) was also determined by the intended use: for the fight against armored opponents it was more wedge-shaped in cross-section and therefore less sensitive, for use against unarmored opponents thinner and thus more suitable for cutting.

The blacksmith can specify the extent and the center of the curvature when forging the raw blade and rework it even after hardening. The blade can also be given a uniform or tapered width, a long or short point ( Kissaki ). The blacksmith can give the blade handle ( nakago ) a certain shape, make the back of the blade round or square, determine the shape of the hardening line (hamon) and influence the structure and appearance of the steel. Grooves and engravings can also be cut into the unhardened areas of the blade.

All these factors are assessed by connoisseurs and collectors according to aesthetic criteria.

Flaw in sword blade (kizu)

There are many errors that can arise in forging or through incorrect handling. A distinction is made between fatal errors that make the blade unusable and non-fatal errors that can be corrected or only disturb the appearance of the sword.

The errors are in detail:

- Karasunokuchi ( か ら す の く ち or 烏 の 口 , "crow's beak"): A crack in the tip of the blade. If the crack runs more or less parallel to the cutting edge, it separates the hardened from the unhardened area. If the shape of the blade is badly damaged as a result, the blade is lost.

- Shinae ( 撓 え ): Minimal bending points that indicate material fatigue due to bending. These points usually run at right angles to the cutting edge in unhardened steel. They are rather harmless.

- Fukure ( 膨 れ ): Inclusions from folding the steel, mostly welding defects from scale or carbon. The inclusions can be exposed during polishing and are extremely ugly. They reduce the beauty and of course the quality of the blade.

- Kirikomi ( 切 り 込 み ): Notch in the back of the blade that occurs during a parade with the sword. These errors are not fatal to the blade. If possible, they are removed as part of a competent polish. With old, already thin blades they are left as evidence of a combat mission.

- Umegane ( 埋 め 金 ): A correction point by a blacksmith to compensate for or cover up a mistake. Umegans are also steel inserts to hide the core steel that emerges from frequent polishing.

- Hagire ( は ぎ れ ): A wedge-shaped notch in the hardness line (Hamon) or a sharp bend in the cutting edge can cause a hair crack called "Hagire". The notch is usually easy to see and not too dangerous to the blade. The crack, on the other hand, is very difficult to see and is also fatal for the blade.

- Hakobore ( 刃 毀 れ ): A coarse, cylindrical notch that does not pull through the hardened steel, but can very well cause a crack.

- Hajimi ( は じ み ): The matting of the blade resulting from re-sharpening. The blade loses its shine. This is a common sign of old age, but otherwise harmless.

- Nioi Gire ( 匂 切 れ ): Either a hardening line that is not clearly contoured at its boundary to the unhardened steel, but the steel is fully hardened. A good grinder can hide this flaw. Or a fatal hardness error: the hardness line does not exist at one point, the steel is therefore not hardened at this point and the cutting edge is not sufficiently hard.

- Mizukage ( 水 影 ): A shadow caused by renewed quenching or hardening of a blade, mostly on the cutting edge at the beginning of the blade.

- Shintetsu ( し ん て つ ): (translated: "Heart-Iron"). Polished blade; the katana's steel jacket, sometimes only a few tenths of a millimeter thick, is polished in one place and the sandwich construction that lies underneath can be seen. Most of the time the sword is “tired” (see Tsukare ).

- Tsukare ( 疲 れ ) (not shown): A thin blade (cutting edge) created by frequent sharpening. Since a frequently used blade often had to be sharpened, material was removed. A blade can not only be sharpened at the edge; To ensure that the overall shape and proportions are retained, the blade must always be completely sharpened. The translation for Tsukare means: "(Material) fatigue"

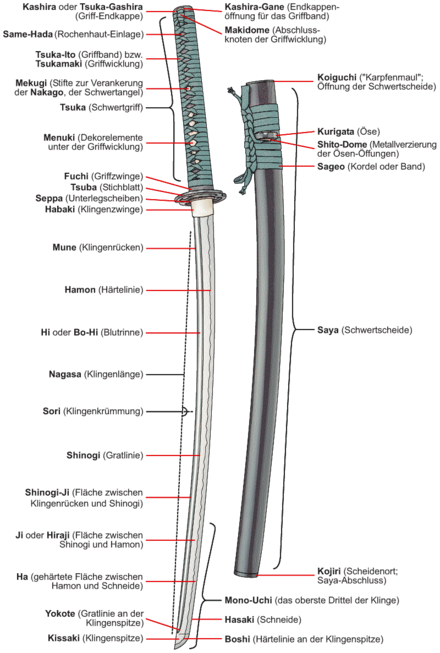

The mount (koshirae)

After grinding, a sheath (saya) and a handle (tsuka) are made for the finished blade from magnolia boards. The scabbard can have an octagonal (with angular or rounded edges), oval or elliptical cross-section. The handle is attached to the sword tang (nakago) ( tang , provided with a mekugi-ana ) with a conical pin made of bamboo (mekugi) inserted through it. The opening of the sheath ( Koiguchi , "carp mouth") is covered with a closure made of horn or bone. The scabbard and the sword handle can also be left in their raw state ( Shirasaya , "white scabbard") if they are only used to store the blade.

For a full assembly (Koshirae) the sheath is painted dust-free; it can be covered beforehand with ray skin (same) or decorated with inlays. The outside is provided with a perforated round button ( Kurigata , "chestnut shape ") to which the sword strap (Sageo) made of silk, cotton or leather is attached. Military weapons can also have a special lock that is designed to prevent the sword from accidentally sliding out of the scabbard.

The complete assembly of a katana also includes the following metal parts:

- the habaki , a clamp at the base of the blade in front of the guard plate , with which the tight fit of the katana is secured in the sheath and the tsuba is held

- the tsuba (guard sheet)

- two Seppa (washers under and over the tsuba )

- the fuchi ( clamp between tsuba and handle)

- the Samegawa (grip coating made of ray skin (same) or other fish skin)

- the tsuka-ito (wrapped around the handle, made of silk ribbon or, more rarely, leather, with decorative swords also cotton. Today often also artificial silk)

- two menuki (relief-like inserts under the wrapping)

- the kashira or tsuka-gashira (cap at the end of the handle)

The decorations of Fuchi, Menuki and Kashira are usually designed with the same motifs or according to a common theme.

For a daisho combination, the decorations of the wakizashi (short sword) are matched to those of the katana.

The classic wakizashi also included the side knife ( kogatana or kozuka (the handle of the kogatana)) and the sword needle ( kogai ) - alternatively a pair of metal chopsticks - which are carried on both sides next to the blade in the saya and through matching openings in the tsuba were plugged. The sword needle was used roughly like an awl we use to repair the movable armor parts connected with silk ribbon or to straighten the winding of the sword hilt.

Sword fencing

A katana was mainly used as a cut, but also as a stabbing weapon, which can be used with both hands and with one hand. The oldest Japanese sword fighting systems date back to the 12th to 13th centuries.

The central element of Japanese sword fighting ( Kenjutsu ) and the arts based on it (such as Iaidō ) is that the blade axis is never struck vertically against the target, but is always guided in a pulling-cutting movement. Thus, the blows are more likely to be seen as cuts. The curved shape of the blade also takes this into account.

The Japanese sword master Miyamoto Musashi wrote the book Gorin no Sho ( The Book of the Five Rings ), in which he explains his two-sword form (Niten-Ryu) and justifies it esoterically. The Kenjutsu , the art of sword fighting in practice, has changed to today's gendai budo . The art of drawing the sword is called Iaidō and is a more meditative form of combat in which an imaginary enemy is fought. Kendō is the art of fencing with a bamboo sword (Shinai) , whereby - similar to European fencing - head protection with a protective grille for the face and armor are worn. This type of sword fighting, depending on the respective style ( ryu ), sometimes takes a competition-oriented direction.

Even today there are numerous traditional ( Koryū ) sword schools in Japan that have survived the general ban on swords imposed by Emperor Meiji . The best known include Kashima Shinto Ryu , Kashima Shin Ryu , Hokushin Ittō-ryū and Katori Shinto Ryu .

Myths and Misconceptions

Japanese blacksmiths have always enjoyed great esteem, and the Japanese emperor Go-Toba (1180–1239) had even learned the art of swordsmithing himself and divided the blacksmiths of the empire into classes, the first of which had special privileges . Famous swordsmiths such as Masamune , Muramasa and others are also reported whose swords possessed a spiritual power that made them superior to other swords. In later times - especially in the Tokugawa Shogunate of the Edo period - the katana was transfigured as the "soul of the samurai". However, at this time the great armed conflicts in Japan had already ended and the samurai had to justify their special position in the newly created rigid corporate state by distinguishing them from the lower classes.

One of the most common misconceptions is that the steel of a blade is folded incredibly often, which is supposed to give it superior strength and quality. Here, however, the number of folding processes is often confused with the number of layers . The number of layers corresponds to two times the number of folding processes, so a bar folded six times already has 2 6 = 64 layers and thus a bar folded 20 times already consists of more than 1 million layers. Likewise, in the West, the misconception is widespread that for the Japanese sword the combination of steel and iron is folded together and forged into a blade. However, this folding process ( fermentation ) affects the preliminary stage, namely the production of the ingots of cutting steel and core steel, which are then welded to form the raw blade. This misunderstanding may be based on a wrong analogy with Damascus steel , which is made using a completely different forging technique.

The multiple folding and processing serves primarily to distribute the different carbon content caused by the steel manufacturing process evenly over the entire length of the blade. This is the only way to ensure that the finished forged blade does not crack and break during the hardening process and, of course, later in combat. The resulting superficial steel structure - called hada - which occasionally resembles the grain of wood ( mokume and itame hada ), is therefore more of a by-product. Over time, however, the different types of hada were classified according to the schemes of the patterns (for example Ayasugi-Hada, Masame-Hada) and form an important characteristic when evaluating a sword.

The katana in the media

With the revival of Romanticism in the second half of the 20th century, the glorification of the European Middle Ages , the Near and Far East became popular again. Above all, Japanese culture exerts a lasting fascination on the recipients of Western culture, which is mainly fed by Japanese films , anime and manga . The depiction of the samurai and their sword fights as well as duels between the manga and anime protagonists contributed significantly to the development of many misunderstandings, which to this day are mostly accepted without criticism. In the last ten years there has been a noticeable media trend towards the transfiguration of Japanese blacksmithing, which is also reflected in popular scientific formats - offered by National Geographic , History Channel and Discovery Channel .

It is often the opinion, also by experts in popular scientific publications, that the Japanese sword represents the pinnacle of swordsmithing in all of human history. However, this claim does not stand up to the archaeological, metallographic and historical sources. The laminate structure of the Japanese blades mentioned above is nothing unusual or unique, as the Celtic swords of the 5th century BC. Chr. (Almost a thousand years before the independent iron smelting in Japan) show a targeted welding of different types of steel. The same applies to Damascus steel . Studies on Roman and Germanic swords ( Spathae and Gladii ) also often show complex damask structures. Especially the worm-colored European blades of the early Middle Ages are hard to beat in terms of their complexity. This is proven above all by the research of Stefan Mäder , who had early medieval blades polished by experts as part of a project in Japan. The results clearly show that even the Saxe consisted of finely colored steel with an even distribution of carbon, composed of different types of steel, welded (ductile core steel and high-carbon cutting steel) and selectively hardened. Selective hardening was also found in late Roman Spathae from the Nydam ship . According to this, neither laminate blades nor refined techniques or selective hardening are something exclusively Japanese or “extraordinary”. Middle Eastern and Central Asian blacksmiths also had extensive know-how at that time as their Japanese and European colleagues and used at least the same processes to produce high-quality sword blades. Swords of the same quality as the Japanese have been made in Europe since the times of the Roman Empire , parallel to India and Persia , where crucible steel production reached a high point in antiquity. Historically, neither the superiority of the Japanese sword over all others nor any special properties of the blade material can be proven.

Ultimately, until the middle of the 20th century, there were no scientific publications that spoke of fundamentally inferior starting material and poor processing of historical European blades. Historically handed down reports concerning the blacksmithing of the Celts ( Diodori Siculi Bibliotheca historica ) and Franks do not reveal any inferiority of the European steel products compared to other cultures. As early as the 19th century it was recognized that the forging processes of ancient Europe ( Celts , Romans ) were basically the same as those still practiced in Japan today. It was also possible to prove from a material science point of view that modern, homogeneous industrial steel is technically superior to any welded joint. Scientific metallographic studies of ancient blades are available from the 1920s.

It can therefore be stated that all historical and modern scientific sources attest to the good steel quality and the distinctive forging skills of European blacksmiths since ancient times. The alleged poor steel quality and inadequate blacksmithing of European blacksmiths is basically a product of popular mass culture of the second half of the 20th century when Japanese blacksmithing became accessible to the general public through the media. The contrast between traditional Japanese forging technology and the romantic notion of Europeans of antiquity and the Middle Ages as "uneducated barbarians" was successfully staged by the film industry and perceived as "historic" by the general public. Even the supposed superiority of damasks or crucible steels over homogeneous fermentation steel cannot be scientifically proven to this day, but has its origin in the romanticism of the 19th century and not least in the romantic literature of Walter Scott . The myth of the inferiority of European steel production and forging technology therefore has no reliable sources.

Primary properties

Furthermore, it is claimed that the katana is practically indestructible due to its soft ductile core and the very hard (up to 61 HRC) cutting edge and cuts steel and organic materials with equal effectiveness. This image of the Japanese sword comes entirely from anime and the romantic transfiguration of Japanese legends. Apart from the fact that heat-treated steel of 45–58 HRC cannot cut such steel, but can only break it, such a view contradicts the laws of physics. A large number of Japanese and European historical and literary sources can be verified that report bent, jagged and broken sword weapons. There have also been reports of use against metal (with serious consequences for the weapon), but an ability to “cut steel like butter” or “cut silk scarves in the air” has nowhere been historically proven, given modern tests and metallographic Investigations of the old sword weapons are not surprising either. Depictions in films, computer games and anime in which stones, solid metal objects or plate armor are cut in two with one blow and without significant material resistance are fiction. In view of the compressive or tensile strength and hardness of iron, steel and rocks, such cuts are physically not possible.

As an exclusive attribute of the Japanese sword, its supposedly phenomenal sharpness is often stated. This seems to have been the case because it was noticed during Hasekura Tsunenaga's visit to Europe in the 17th century. This claim is derived from the fact that the hardness of the edge of the katana usually exceeds that of the European originals (55-58 HRC against 64-67 HRC of the Japanese katana). The hardness of the cutting edge actually has no effect on the sharpness itself - edge retention and sharpness are confused here. In fact, a lower ductility of the cutting edge steel can even be detrimental to the sharpness in the microscopic range. The soft core and the back of the blade ( mune ) of the katana also ensure that the weapon bends quickly under load, because this is the only way to absorb the tension and keep the hard edge intact. This also explains the many nicks and bends on historical Japanese blades. With stiffer blades and a higher core hardness, the risk of chipping on the cutting edge increases, as expected, if the load is too high. The frequently quoted “hardness with simultaneous elasticity” is therefore a compromise and not a combination of two opposing properties.

There is also the opinion that katanas are very thin compared to other swords, which leads to a steep blade geometry and thus extraordinary cutting performance. Often, of all things, European sword weapons are assumed to be extremely thick; possibly only because the visibly wider blades are automatically assumed to be thicker, or because of the fencing weapons that appear thick due to their striking edge and are used in stage fencing and exhibition combat. The fact is, however, that a Nihonto blade is 6 to 9 millimeters thick and this thickness hardly decreases towards the place (Kissaki), while European swords are up to 8 mm thick at the blade root and sometimes only 2 mm thick in the local area. Japanese swords are actually thicker than z. B. the original swords of the European Middle Ages.

Ultimately, the blade thickness is only one of several macroscopic quantities that, together with the microscopic structure, define the sharpness of a blade.

Fencing system and area of application

The Kenjutsu fencing system associated with the katana is often treated very imprecisely in popular scientific print media and TV broadcast formats. The boundaries between kendō , kenjutsu and aikidō are mostly blurred and a modern sport like kendō is often mistakenly referred to as the “ancient art of sword fighting”. The public's perception of Japanese sword fighting is largely based on samurai films, Hollywood depictions of the Far East or, especially among young recipients, on anime series such as Naruto or Kenshin . Concepts of an intrinsic killing potential of a weapon come from computer games and have nothing in common with real edged weapon use. Because of this tendency and the widespread misunderstandings from the 18th and 19th centuries regarding European sword weapons , the opinion is often expressed that the katana is superior to all other swords in terms of speed because of its allegedly low weight compared to other bladed weapons. But if you consider the fact that an average katana, like the European combat sword (type X to XIV according to the Oakeshott classification ) weighed around 1100–1200 grams, the above remains the same. Claim at least doubtful. The saber (0.9–1.1 kg), the rapier (up to 1.4 kg) and the Roman-Germanic spathe (0.6 to 1.2 kg) were also available in weights below 800 grams (e.g. the Russian-Caucasian shashka ). This means that the katana is in the middle of the range in terms of weight. The two-handed guidance with an average blade length of around 70 cm also has its counterparts in other cultures (e.g. the European long knife ). In reality, there are no logically comprehensible reasons for a significantly faster method of fencing with the katana than with other historical fencing styles. Arguments such as the historical absence of highly developed fencing teachings and qualitative useful weapons among other peoples outside the Sino-Japanese cultural area do not correspond, from a scientific point of view, to the archaeologically and historically proven facts.

There are also misunderstandings that go the other way; it is often claimed that Nihontō were pure cutting weapons and were only suitable for fighting unarmored opponents. The fact that today almost all authentic Japanese swords are forged for sporting activities such as Tameshigiri and Iaidō plays a major role . The so-called Koto swords ("old swords", roughly speaking before and during the 16th century) have a high variability in terms of blade geometry, curvature, balance and weight, whereby the basic concept of the Nihontō always remained the same. Their primary task was to combat Japanese armor, which included iron and steel (e.g. helmets). That is why the classic Japanese swords from the time of the wars and conflicts before the Tokugawa shogunate are optimally adapted to the armor of the time and are therefore suitable for more than just cutting soft targets. An important distinction; the katana in its current form did not emerge until the 17th century, the battle swords before the Tokugawa shogunate were generally not katanas and were used accordingly differently.

The specific application of the katana is very often neglected or distorted. It is stated, among other things, that the katana is ideally suited to combat any type of armor and can be used in almost every conceivable combat situation. But such ideas clearly show the influence of modern samurai and ninja films, which usually have nothing to do with historical warfare. Until the Edo period , the samurai were primarily mounted archers, with their tachi sword only being used in an emergency. It was not until a decree of the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu that the katana, which emerged from the Uchigatana in the 15th century, was transfigured as the “soul of the samurai”, with the classical wars on horseback in full armor moving into the past forever. The katana itself was from the start a personal dueling weapon for weakly or not at all armed opponents, which only attained its final form (mounting, polishing, design) in the 17th century. As a result, the katana of the 17th to 19th centuries hardly came into contact with lamellar armor , breast armor or traditional Ōyoroi armor of earlier times. Their alleged armor-piercing properties or their universal suitability for all matters of the battlefield are without any historical basis. In contrast, it should be noted that the European swords of the High and Late Middle Ages , Central Asian sabers and Middle Eastern bladed weapons often had to endure peak loads when fighting chain armor , lamellar armor or even plate armor , which could never occur with Japanese armor - cutting through chain mail or Piercing the plate armor at the appropriate point places very high demands on the blade material and the heat treatment of the blade. The structure and hardening of the katana are therefore technically unsuitable for fighting plate armor or chain armor, this specific, relatively young type of sword (not to be confused with Tachi or Nihontō per se) served exclusively representative purposes and as a dueling weapon against unarmored opponents.

Metallurgical backgrounds

One of the most common arguments to prove the superiority of Japanese blades is the claim that the iron doll - tamahagane - from the Japanese racing furnace ( Tatara ) is particularly pure or consistently contains high amounts of alloy components such as molybdenum , vanadium or tungsten . However, the raw pellet from the racing furnace is a random product, the content of slag and carbon can vary widely. As a result, every piece of Tamahagane is absolutely individual. The blacksmith's specialist knowledge allows him to choose suitable pieces that should be as free of slag as possible and have a carbon content between 0.8-1.3%. The Japanese iron ore in the form of “satetsu” (iron sand) was qualitatively only of mediocre to inferior quality, which is why the lengthy refining techniques of folding and forging were necessary to clean the steel (see Yoshihara, Tanimura). The quality of Japanese steel and the great skill of the Japanese blacksmith lies more in their ability to forge good to very good blades from mediocre raw materials. This also explains why the Japanese blacksmiths used European export steel ("Namban-Tetsu") at the time of the Namban trade and afterwards. The quality of Japanese blades is therefore not based on the quality of the raw material as such.

As far as the alleged alloy components are concerned, these were not found in significantly increased amounts in metallographic examinations. Apart from the fact that a racing furnace cannot raise the temperature required for the production of low or high-alloy steels, modern steels, despite all possible combinations of the above-mentioned elements, do not have the “amazing properties” that the media often attribute to Japanese steel. The presence of molybdenum and vanadium in significantly high proportions as well as nano-structures in Japanese steel has actually not yet been proven; it is basically a false analogy to Wootz and the role of vanadium as a carbide- former, which is due to poorly careful media coverage.

The sword care

The katana is usually cleaned and maintained in a certain order and with various utensils (provided there are no nicks , which makes the use of whetstones necessary).

- If possible, acid-free, special paper ( Japanese paper = nuguigami) is used to remove surface dirt and old camellia (tsubaki oil, tsubaki abura) or clove oil (choji oil). Nuguigami must be intensively "kneaded" before use to remove all coarse particles, otherwise it can lead to extremely fine scratches on the blade - this depends on the quality of the paper. If necessary, chlorine-free cellulose toilet paper or handkerchiefs without perfume or active ingredients such as aloe vera are also possible .

- The blade can be powdered with limestone powder (Uchiko) if it is dirty. This has a cleaning and slightly polishing effect without creating scratches. With a new piece of Japanese paper (nuguigami) and the powder, oil residues and impurities are polished away.

As part of normal cleaning, it is sufficient to gently wipe the surface without exerting significant pressure. Areas with visible, slight rust film or the consequences of splashes of saliva, fingerprints or the like can also be removed with Uchiko to a limited extent. You should never try to 'repair' the affected areas quickly by rubbing them firmly. The result would be a scratched or polished area and a destroyed polish. Using the highest quality Uchiko (i.e. finely ground), the affected areas should instead be treated with only minimally increased pressure (compared to treating the rest of the blade surface) and only briefly. Then lightly oil the blade (see below) and only repeat the procedure after a few days. This type of "repair" can take several weeks or even months and requires perseverance and patience until the damaged area has disappeared, but this is the only way to achieve a largely polish-preserving repair. In the event of major damage or if the recommended procedure no longer helps, all that remains is to re-polish.

However, the long-term use of Uchiko also contributes significantly to the “fatigue” of the polish due to its minimally abrasive (surface-removing) properties. Therefore, the frequency of using Uchiko to clean blades should be kept to a minimum. The renewal of a polish is always an abrasion process and a "Togi" (Japanese professional sword polisher) is not found on every corner outside of Japan. An alternative or supplement to Uchiko is high-purity ethanol (alcohol, alcohol, at least 90%) from the pharmacy. After the first, dry wiping of the blade with the nuguigami (Japanese paper, see above) or a piece of chlorine- and acid-free, soft cellulose, a new, clean piece of paper is moderately soaked in 90% ethanol, with which the blade is then wiped in long strokes and without great pressure. The wiping hand is always guided along the blade from the blunt back of the blade in order to avoid cuts. Wait briefly until the alcohol visibly evaporates and the blade is dry, then wipe again briefly with a new, dry, soft piece of paper and finally oil the blade as described below. 90% ethanol is basically suitable for all katana steels, both historical (Tamahagane) and modern. In the case of valuable blades, a test cleaning of a small non-critical area, e.g. B. of the Ji under the habaki surface.

An important note: The small area of Ji (lateral blade surface) under the Habaki (blade collar) should always with any cleaning in the direction of the Nakago (Angel) towards wiped, never in the direction of the blade! This place is a dirt trap, often metal particles from the habaki or rust particles from the nakago (fishing rod) also accumulate there. Wiping in the direction of the blade will then push it onto the blade surface and cause scratches over time. When oiling, this area should also be treated with an extra oil cloth or with an oil-moistened fingertip (work in the direction of fishing), but not with the same cloth that is used to treat the rest of the blade body.

- After cleaning, the blade is oiled again with special camellia or clove oil. You use a Yoshinogami cloth (very thin Japanese paper) or cotton wool. A fresh piece of cellulose or Japanese paper is used for this. Clove essential oil, as can be bought in pharmacies in Europe, is completely unsuitable and can damage the blade. The oil should be used very sparingly so that a wafer-thin oil film forms. This film protects the blade from rust film and humidity. 1-2 drops are completely sufficient. However, there must not be any oil "standing" on the blade, because otherwise wood particles and dust from the sheath would stick to the blade. Moving the blade in the saya would then cause scratches. This maintenance procedure should be repeated at least every three months, depending on the humidity.

- The swords can be completely dismantled; the blade is fixed in the handle (tsuka) with a pin (mekugi) made of bamboo, horn or wood, rarely made of metal. The pin can be pushed out if necessary using a small hammer-like tool (mekuginuki) made of brass . In the case of old originals, you should not change the rod or nakago (remove rust, grind or oil), but consult a specialist, as the rod, its condition and, if necessary, the inscriptions are important for the classification (age / authenticity) and value assessment .

- If you want to examine or hold the blade, you use a piece of silk fabric (fukusa). You shouldn't touch a blade with your hand. In the past, you even had to hold a piece of paper between your lips in order not to create contamination through breathing.

literature

- WM Hawley: Laminating Techniques in Japanese Swords. Hawley, Hollywood CA 1974, OCLC 7198357 , WM Hawley Publications, 1986, ISBN 978-0-910704-54-0 (reprint).

- Leon Kapp, Hiroko Kapp, Yoshindo Yoshihara: The Craft of the Japanese Sword. Kodansha International, Tokyo 1987, ISBN 0-87011-798-X , (English).

- German: Leon Kapp, Hiroko Kapp, Yoshindo Yoshihara: Japanese swordsmithing. Ordinance, Eschershausen 1996, ISBN 978-3-931425-01-2 .

- Kanzan Sato: The Japanese Sword. A Comprehensive Guide. Kodansha International, Tokyo 1983, ISBN 4-7700-1055-9 (English).

- John M. Yumoto: The Samurai Sword. A manual. Ordonnanz-Verlag, Freiburg 1995, ISBN 978-3-931425-00-5 , (translation of the original: The Samurai Sword. Tuttle 1958, ISBN 978-0-8048-0509-4 ).

- Markus Sesko: Lexicon of Japanese swordsmiths A – M. Norderstedt, ISBN 978-3-8482-1139-5 .

- Markus Sesko: Lexicon of Japanese swordsmiths N – Z. Norderstedt, ISBN 978-3-8482-1141-8 .

Web links

- Michihiro Tanobe: The Beauty of the Japanese Sword. History and Traditional Technology . arscives.com, brief history, accessed on February 10, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rochenleder on materialarchiv.ch, accessed on April 14, 2017.

- ↑ How Long Is a Katana? In: Medieval Swords World. August 3, 2019, Retrieved September 9, 2019 (American English).

- ↑ How Much Does a Katana Weigh? In: Medieval Swords World. August 2, 2019, Retrieved September 9, 2019 (American English).

- ↑ Kōkan Nagayama: The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords. Kodansha international, 1997, ISBN 4-7700-2071-6 , p. 71 ff.

- ^ Alan Williams: The Knight and the Blast Furnace. Brill Verlag, 2003, ISBN 978-90-04-12498-1 .

- ↑ Stefan Mäder: Steels, stones and snakes. On the cultural and technical history of sword blades in the early Middle Ages. Dissertation, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2001, online (PDF; 30 MB), on schwertbruecken.de, accessed on February 10, 2017. In: Zeitschrift für Archäologie des Mittelalters. 40, 2012 (2013), 207-209. Book: Museum Altes Zeughaus , Solothurn, 2009, ISBN 978-3-033-01931-7 .

- ↑ Ars Martialis: Damascus blades

- ↑ Ex omnibus autem generibus palma Serico ferro est “Among all varieties, however, the palm belongs to the seric iron; the Serer send it along with their robes and furs; the Parthian has second place. ”Pliny, Naturalis historia XXXIV, 41. On archaeologie-online.de, accessed on February 10, 2017.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland and Brian Gilmour Oxford: Medieval Islamic Swords & Swordmaking: Kindi's Treatise “On Swords and Their Kinds”. The E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust 2006, ISBN 978-0-906094-52-5 .

- ^ Richard F. Burton : The Book of the Sword. 1884, archive.org , Barnes & Noble Books, New York 1972, ISBN 978-0-06-490810-8 (reprint).

- ↑ Manfred Sachse : Damascus steel. Myth. History. Technology. Application. 2nd edition, Verlag Stahleisen GmbH 1993, ISBN 978-3-514-00520-4 .

- ↑ B. Zschokke: You Damasse et des Lames de Damas. 1924, OCLC 891510843 , In: Revue de métallurgie. 21, 11, 1924, online .

- Jump up ↑ Sword Tests in Nagano Prefecture in 1853 .

- ↑ Utagawa Kuniyoshi : Image 3: Ishikawa Sosuke Sadatomo. At welt-der-samurai.de, accessed on February 10, 2017.

- ↑ Miniature from the Maciejowski Bible. Folio 45 verso. ( Memento from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) On manesse.de, accessed on February 10, 2017.

- ↑ The notch at Skofnung. From thearma.org, accessed February 10, 2017.

- ↑ Dr. Stefan Mäder on steel myths. At archaeologie-online.de, accessed on February 10, 2017.

- ^ Leon Kapp, Hiroko Kapp, Yoshindo Yoshihara: The Craft of the Japanese Sword. Kodansha Intl, 1987, ISBN 978-0-87011-798-5 .

- ↑ Hiromi Tanimura: Development of the Japanese Sword. In: Journal of The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society. 32 (2), Feb. 1980, pp. 63-73, doi: 10.1007 / BF03354549 .

- ↑ a b About the sharpness of blades . Site of Tremonia Fencing. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ Measurement data of historical swords from Zornhau.de: ZEF 11 (PDF; 123 kB).

- ↑ Measurement data of historical swords from Zornhau.de: ZEF 12 (PDF; 36 kB).

- ↑ Measurement data of historical swords from Zornhau.de: ZEF 15 (PDF; 45 kB).

- ↑ Kabuto-Wari, one of the classic test methods for determining the blade quality.

- ↑ Yoshindo Yoshihara: Tamahagane in the Google book search

- ↑ Hiromi Tanimura: Development of the Japanese Sword. 1980.

- ^ M. Reibold, P. Paufler, AA Levin, W. Kochmann, N. Pätzke & DC Meyer: Materials: Carbon nanotubes in an ancient Damascus saber. In: Nature . 444 (7117): 286, 2006, doi: 10.1038 / 444286a , online at innovations-report.de, accessed on February 10, 2017.

- ↑ JD Verhoeven, AH Pendray, WE Dauksch: The Key Role of Impurities in Ancient Damascus Steel Blades. In: JOM. 50 (9), 1998, pp. 58-64, doi: 10.1007 / s11837-998-0419-y , online at tms.org, accessed on February 10, 2017.