Natural monopoly

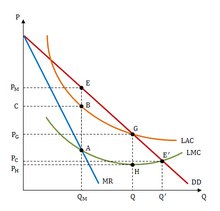

In microeconomics, a natural monopoly is a situation in which, due to high fixed costs and low marginal costs, there are particularly pronounced increases in economies of scale ( subadditivity ). In this case, the total costs of providing a good are significantly lower if only one company and not several competing companies supplies the market.

In theory, public utilities in particular , where very high fixed costs for setting up a network (e.g. traffic routes, telephone, post, energy and water supply networks) are compared with comparatively low operating costs, are mentioned as an example of natural monopolies. In the context of digitization , costs can also be linearized and thus a natural monopoly.

The natural monopoly is to be distinguished from the artificial monopoly , cartels and the legal monopoly .

Basics of the model

Economic theory foundation

The term natural monopoly is not defined uniformly in economics . Every market constellation in which a single economic agent can produce a good at lower cost than two or more economic agents is often referred to as a natural monopoly. “It was already mentioned above that there can be markets in which only one provider will survive in the long run. Such natural monopolies are characterized by certain cost structures, which are summarized under subadditivity. This means that each supply volume can be produced more cost-effectively by a single company than by several companies. "

This is precisely the case when there is strict subadditivity in the costs over the entire output area under consideration, i.e. one company can produce the entire quantity of goods at lower costs than several smaller companies that produce the required quantity in total. Formally this is expressed by: where the cost of production is the amount that suppliers would produce; these partial amounts add up to the total amount .

However, this applies to a great many market constellations, especially to most of the narrow oligopolies . Even low fixed costs , combined with possibly high but constant marginal costs , lead to monotonously falling unit costs , which as a rule does not, or at least does not necessarily, lead to a monopoly of the company.

In a perfectly informed social planner situation, a monopoly would be preferred in the case of subadditive costs. In a real world with imperfect information and imperfect regulation, however, a balance has to be found between the advantages of competition on the one hand and the cost disadvantages due to the presence of several companies on the other.

The term should therefore be defined more narrowly. The undisputed (narrowest) definition is: A natural monopoly always exists when only one company can cover the market and cover its costs.

Even if two companies could cover their costs in the market, it can make economic sense to support a monopoly position if the avoided costs more than compensate for the advantage of the competition.

scope of application

Natural monopolies are primarily based on line-related supply networks, such as B. power lines, railways, roads, airports or telecommunications cables. This applies to goods that are dependent on an appropriate infrastructure to provide their services (electricity, gas, water, telecommunications, postal services, transport).

In the case of power supply, for example, only the transmission of electricity is to be understood as a natural monopoly: more or less twice the number of power plants is required to produce twice the amount of energy. For the transmission, on the other hand, the existing infrastructure (power poles, substations, etc.) can be expanded to twice the capacity relatively inexpensively. A provider with two lines on one power pole can offer the product cheaper than two providers with one line per power pole. Therefore, the only exception area is network operation for the transmission and distribution of electricity, which is to be legally and operationally separated from the other stages of the value chain (generation, trading and sales) within the framework of so-called unbundling .

As a rule, not the entire industry will have the characteristics of a natural monopoly. In the case of the provision of electricity, gas, telephone services or the railway, only the provision of the network is to be understood as a natural monopoly (one speaks of a monopoly bottleneck because here many energy producers or railway operators come across a single network operator and it is therefore "tight") .

In addition to the criterion of costs, the special position of the natural monopoly is emphasized if the criterion of the irreversibility of costs is also given for potentially new market providers. Irreversibility is present if a potential new market provider has to write off the value of his expenses or production factors irretrievably when leaving the market (so-called sunk costs due to the high specificity of the investments ).

The problem of natural monopoly also comes into play when the market for a certain product is manageably small and the development makes up a considerable part of the total costs. A typical example is the model railroad industry: the demand for each model is limited, but the models are expensive to develop. A model railway manufacturer produces a specific locomotive that devours one million euros in development costs . On the other hand there are 10,000 model railroaders who want to buy exactly this locomotive series - there is no greater demand for this model. Now the development costs have to be divided among the customers, then, neglecting the production costs, the unit price is 100 euros. However, if a competing company wants to bring the same or a very similar model onto the market in the same quality, it must also invest the million euros in development costs. In simple terms, the 10,000 interested parties are divided equally between the two companies, so that each manufacturer sells 5,000 units. The unit price increases to 200 euros for both manufacturers to cover the development costs that are now double. This rise in costs leads to falling demand and suffocates supply to such an extent that there is probably only one manufacturer for the next model - the natural monopoly comes into play.

Extended scope

If one takes a broad concept of monopoly as a basis, which includes not only actual sole providers but also providers with great market power ( quasi-monopolists ), software providers with a high degree of widespread use of their software can also be viewed as "natural quasi-monopolists" as an application of the theoretical model.

With the economic development of the Internet, the importance of natural monopolies has increased. First, the procurement, production and distribution of digitizable goods - for example user software or electronic services - are associated with high fixed costs and low variable costs, so that dominating providers can realize economies of scale and thus higher profits with increasing sales. Second, the benefits of network goods and network services grow with the number of players on the supplier and demand side, so that positive network effects arise. The more users that can be reached via the e-mail infrastructure, for example, the greater the overall benefit of this infrastructure, which continuously attracts additional users. On the provider side, there are positive network effects when an established system stimulates the production of further variants and components - for example plugins for an established browser.

Natural quasi-monopolies should now arise when there are positive feedback loops between economies of scale and positive network effects: The increasingly favorable cost structure of the dominant provider creates scope for price reductions that attract additional users, thereby increasing the overall benefit of the system, which gives the provider additional economies of scale bestows etc.

Examples from the internet economy for natural (quasi) monopolies are the eBay marketplace, in addition to which only smaller, highly specialized auction providers can exist in some countries, the replacement of the numerous B2B marketplaces of the “New Economy” with a few dominant marketplaces or the software from Microsoft, which is installed on most computers worldwide.

Government measures as a remedy

The supply can be taken over by the state ( state monopoly ).

State regulation of the market can consist of regulatory requirements (e.g. maximum price regulation ), a legal restriction of the economic activities of the monopoly or a structural breakdown of the monopoly company.

Recently, unbundling has been widely used as a solution to the problem of natural monopoly. Network monopoly and production are separated. Examples are water, electricity, gas, and telecommunications. The network monopoly is retained as a natural monopoly and regulated by the state. The company operating the network must, however, allow competitors to pass through the actual products (water, electricity, gas or telecommunications) on terms specified by a regulatory authority. The type of regulation differs significantly depending on the country. In Germany, for example, a transmission competition in the water supply is not the chosen form of regulation.

Remedy through technical progress

However, some natural monopolies will disappear by themselves over time. For example, the invention of the automobile threatened the former natural monopolies of railway companies. Technical progress therefore sometimes leads to the dissolution of a natural monopoly. In this context, one speaks of competition for substitution .

criticism

Vulnerability of natural monopolies

Following William J. Baumol's theory of contestable markets , the view is that the existence of a natural monopoly is not a market failure because competition is not visible in the form of multiple suppliers , but it works in a latent way.

Criticism from libertarians and anarcho-capitalists

With regard to the pipeline networks used as historical examples of the existence of natural monopolies, it is argued that they arose as a monopoly position granted and secured by the state. According to Thomas DiLorenzo, these state monopolies were only justified in retrospect from an economic point of view .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hal R. Varian : Intermediate Microeconomics . 7th edition ( International Student Edition ), New York 2006, ISBN 0-393-92702-4 , pp. 435 f.

- ↑ Ferry Stocker, Moderne Volkswirtschaftslehre , 6th edition 2009, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, ISBN 978-3-486-58576-6 , page 75

- ^ Cezanne, Allgemeine Volkswirtschaftslehre , 6th edition 2005, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, ISBN 3-486-57770-0 , page 63

- ↑ Robert S. Pindyk, Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics , person-Verlag, 6th edition, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-8273-7164-5 , S. 477th

- ↑ Anton Frantzke : Fundamentals of Economics. Microeconomic theory and tasks of the state in the market economy , Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 1999, p. 220 ff.

- ^ Ralf Peters: Internet Economy . Jumper; Edition: 2010 (April 16, 2010). ISBN 978-3642106514 . Page 15.

- ↑ Vahlen's Compendium of Economic Theory and Economic Policy, Volume 2, p. 88

- ↑ "A so-called" natural monopoly "exists when an offer from several competing producers does not make economic sense." Glossary of the Federal Ministry of Finance ( Memento of the original from November 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and still Not checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ According to the Federal Ministry of Finance in its glossary ( memento of the original dated November 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Vimentis , Why is the Market Failing ? , Edition of June 20, 2007 (online as pdf ).

- ↑ Ferry Stocker, Moderne Volkswirtschaftslehre , 6th edition 2009, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, ISBN 978-3-486-58576-6 , page 77

- ↑ Baumol, WJ; Panzar, JC & Willig RD (1982) Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure .

- ↑ DiLorenzo, Thomas J. (1996), The Myth of the Natural Monopoly (PDF; 992 kB), The Review of Austrian Economics 9 (2).