Physionotrace

The Physionotrace (from French physionomie "Physiognomie" and tracé "Outline") is a device used from 1786 to around 1830, especially in Paris, in the form of a further developed silhouette chair to rationalize the production of profile portraits. Also and above all an etching prepared with this device is consistently referred to as a Physionotrace. The US spelling is "Physiognotrace".

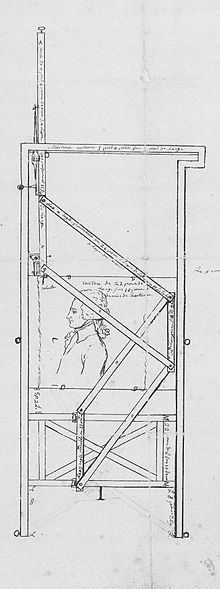

The mechanism

The illustrated drawing from the Bibliothèque nationale de France is the only image source for the approximately 1.70 m high device, comparable to a silhouette chair, on the side of which the person to be portrayed sat. The movable element of a pantograph frame formed from parallelograms (top left in the drawing) was connected to a long thread leading into the background of the room (not visible in the drawing), with which the profile contour of the seated person was traced. The pantograph transferred this contour line onto a piece of paper stretched underneath. During the session, which lasted a few minutes, the artist completed the interior drawing of the portrait free-hand, so that initially a life-size representation was created, as can be seen on the drawing. From this sheet, with the help of a second, scaling-down pantograph, the main features of the portrait were later transferred in the form of dotted lines onto a copper plate that had previously been prepared by etching. This printing plate was completed using the etching technique , usually combined with aquatint .

The portraits

Typically, the round (sometimes oval, rarely rectangular) profile representations have a diameter of about 6 cm, the pressure plates have a dimension of 7 × 6 to 9 × 8 cm and they were z. B. on 15 × 12 cm large papers in an edition of at least twelve copies. However, up to 2000 prints were possible. Not only are the manufacturer's signatures indicated on the prints, but in an unusual way the complete address advertises a visit to the studio in the inscription below (e.g. Dess [inée] et Gr [avée] par Bouchardy Suc [cessor] de Chretien, inv. [Enteur] du Physionotrace. Palais Royale No. 82 à Paris ). The term Physionotrace is also highlighted like a brand name on each copy. Over 6000 different portraits using this technique are said to have been created between 1786 and 1830.

The workshops

Gilles-Louis Chrétien (1754–1811) invented both the process and the term "Physionotrace" in 1786 in Versailles. A little later he established himself in Paris and secureda popularitywith several portraits of famous contemporaries (the Dauphin , Anne Louise Germaine de Staël , Jean Paul Marat , Maximilien de Robespierre ), which also brought numerous foreign visitors to Paris to his studio. From 1788 to August 1789 he employed Edme Quenedey (1756-1830) whose portrait drawings he etched. From December 1789, the miniaturist Jean Fouquet wasdrawing in his workshop, who was replaced in this role by Jean Simon Fournier (active until 1799?, At the latest until 1805).

The aforementioned etcher Edme Quenedey started his own business as a physionotracist in Paris in 1789, worked in Hamburg from 1796 to 1801 and then again in Paris until his death.

There are a few by Pierre Gonord (1755–1799 verifiable), undated, but z. Portraits that can be localized to the Hague and are referred to as “dessiné au Physionotrace”. The miniatures and medallions on wood and ivory repeatedly mentioned in the literature in connection with this technique have nothing to do with the Physionotrace, they come from his son Francois Gonord.

Bouchardy père (1797–1849), a miniature painter, took over Chrétien's workshop after Chrétien's death. It is uncertain whether Bouchardy's son Etienne also took part in it.

Charles-Balthazar-Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin , emigrated to America in 1793, worked successfully in Canada, Burlington and New York and physio-trained several presidents.

John Isaac Hawkins received an American patent on a modified Physionotrace machine in 1802 and returned to London in 1803.

Cultural-historical classification

The silhouette ( silhouette portrait) and generally the preference for the portrait seen in profile was a fad of the decades around 1800. It is related to the strict, formalized period style of classicism, the contemporary interest in physiognomy and one in the years immediately after the French Revolution rapidly increasing need of the bourgeoisie for inexpensive, reproducible portraits. Chrétien's invention was contemporary, but not fundamentally original. It was preceded by the silhouette chair, which had been in use for some time and which had become generally known through an illustration in the Physiognomische Fragmenten (2nd book, 1776) by Johann Caspar Lavater , as well as various other attempts to reduce the silhouette with a mechanical reduction by the pantograph and the copperplate engraving for portrait production. In addition to technical support, what is new for the production of portraits is, above all, the work-sharing process of image production, and so the small round copperplate engravings made with the help of the Physionotrace were called forerunners of photography early on. Even the organization of the business process looks extremely modern: The customer Chrétiens bought a ticket in the elegant shop at the Palais Royal for the meeting that was scheduled four weeks later in a workshop on the side street, and a further 14 days later he was able to pick up the engraving plate and 12 finished prints. The last dated Paris Physionotrace portraits were made in 1829. This means that in the decade before photography was invented (1839), the physionotrace no longer played a significant role as an image medium.

Artistic importance

The artistic quality and the demands on the skills of the draftsman have often been underestimated in view of the routine production method of a Physionotrace portrait. On the other hand, it should be noted that the mechanical tracing of the outer profile could theoretically be layman's work, but the interior drawing always required the hand of a quick, confident and experienced portraitist. It was not for nothing that even Chretien employed professional miniaturists for this activity almost all the time. The implementation in the copperplate was more of a manual, albeit demanding, task.

literature

In the German-language literature there was no reliable description of the Physionotrace apparatus and the studios working with it until 2011, hence the detailed description above and in the following the thorough list of the French sources used:

- Henry Vivarez: Un précurseur de la photographie dans l'art au portrait à bon marché: le physionotrace . In: Bulletin de la Société archéologique, historique et artistique "Le vieux papier", Lille 1906. - 36 p. (Reprint under the collective title: Sobieszek, Robert: The prehistory of photography, five texts, from the series "The sources of modern photography ", New York 1979. - Material-rich representation, but uncertain in the technical interpretation).

- G. Kowalewski: BouMagie and Physionotrace. A contribution to the history of the portrait in Hamburg . In: Journal of the Association for Hamburg History, Vol. XXII, 1918, pp. 168–179 (on Lavater and the technical precursors of the invention as well as on Quenedey's activity in Hamburg).

- Gabriel Cromer: Le secret du physionotrace, la curieuse "machine a dessiner" de G.-L. Chretien , in: Bulletin de la societe archeologique, historique ct artistique, “Le Vieux Papier”, 26th year, October 1925, pp. 477-484.

- Gabriel Cromer: Nouvelles précisions, nouveaux documents sur le physionotrace , in: Bulletin de la Société archeologique, historique et artistique “Le Vieux Papier”, 1928, pp. 289–316.

- Rene Hennequin: Un "photographe" de la Revolution et de l'Empire. Edme Quenedey des Riceys (Aube), portraitist au physionotrace (1756-1830), sa vie et son ceuvre , Troyes 1926-27.

- Peter Frieß: Art and Machine , Munich 1993. pp. 131–142 (technical description of the French Physionotrace incorrect, detailed about profile portrait machines ; to the American Physionotracists).

- Gisèle Freund : Photography and Society , (German) Munich, 1976 (description of the technology misleading, appropriate cultural-historical classification).

- Martin Kemp : The science of art , New Haven 1990, p. 186 (correct, but summarized).

- Alfred Löhr: The Physionotrace. How Mayor Smidt got his profile. In: Leather is bread. Contributions to the North German regional and archive history, Festschrift for Andreas Röpcke . Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin 2011, ISBN 978-3-940207-69-2 , pp. 201-216.

- The probably unprinted diploma thesis by Jacques Dubois at the Université de Paris IV .: Portraits au physionotrace from 1999 could not be viewed for the article.

Individual evidence

- ↑ see article Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin in the English Wikipedia

- ↑ see article John Isaac Hawkins in the English Wikipedia

- ↑ The Physionotrace. In: Journal des Luxus und der Moden \ Volume 3 \ October 1788. p. 419 (contemporary report on the "drawing machine invented by GL Chrétien in Paris, as it was manufactured in a similar way by the Jena court mechanic Georg Christoph Schmidt")

- ↑ Vivarez, 1909

- ^ Morris, Diary of the French Revolution, Cambridge (Mass.) 1939, pp. 49, 50, 85, 108

Similar devices

- The camera lucida from 1806 is a purely optical drawing aid.

- The silhouette chair by Ludwig Julius Friedrich Höpfner , around 1790.

Web links

- Here is an uncut image of Quenedey's construction drawing

- New research on the Physionotrace in the US