Polkelly Castle

| Polkelly Castle | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pokelly Hall and Balgray Mill |

||

| Alternative name (s): | Pokelly Castle | |

| Creation time : | 14th Century | |

| Castle type : | Niederungsburg (Tower House) | |

| Conservation status: | Burgstall | |

| Standing position : | Scottish nobility | |

| Construction: | stone | |

| Place: | Fenwick | |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 40 '34 " N , 4 ° 27' 20.6" W | |

| Height: | 160 m ASLTemplate: height / unknown reference | |

|

|

||

Polkelly Castle , also Pokelly Castle , is an abandoned lowland castle near the village of Fenwick , north of Kilmarnock in the East Ayrshire administrative division of Scotland . There are records of the castle under the names Powkelly (around 1747), Pockelly (around 1775), Pow-Kaillie , Ponekell , Polnekel , Pollockelly , Pokellie , Pathelly Ha and Polkelly . The name Powkellie appeared around 1564, when the property was in the hands of the Cunningshams of Cunninghamhead .

history

The Polkelly lands

There is evidence that the Polkelly lands were in the hands of the Comyns until the 1390s . The site was important to the Rowallan Lairds as it provided unimpeded access to the large and important pastures of Macharnock Moor (now Glenouther Moor ).

According to a confirmation Charter of 1512 which consisted Baronat Polkelly from Darclavoch , Clonherb , Clunch with its mill, Le Gre , Drumboy , the lands of Balgray with its tower, its fortress, its mansion and its mill, and the common ground of Mauchirnock (today Glenouther ). The Lainshaw Register of Sasines recorded that Laigh and High Clunch were part of the lands and baronate of "Pollockellie" or "Pokellie".

Dobie reported that the Mures owned "Pow-Kaillie" which extended over 2,400 acres (960 hectares), 2/3 of which were fertile.

The origins of the Polkelly and Rowallan lands as a unit could date back to the British period of the Kingdom of Strathclyde , as evidenced by certain anomalies and coincidences at the boundaries of these lands.

The castle

Polkelly became the second center of power in the Baronate Rowallan. It lost its importance when Balgray became the main town of the Baronate Polkelly in 1512. The castle was near the Balgray Mill Burn . The remains of the castle were removed in the 1850s and used to build a road, so that only a mound with a floor area of 23 meters × 16 meters remained.

Lairds

A Gulielmus (William) de Lambristoune witnessed a charter with which the lands of "Pokellie" (Polkelly) were transferred from Sir Gilchrist More to a Ronald Mure around 1280 . During the reign of King Alexander III. (1241–1286) owned Sir Gilchrist Mure Polkelly and had to seek refuge there until the King could subject Sir Walter Cuming . For the sake of peace and security, Sir Gilchrist married his daughter to Sir Walter.

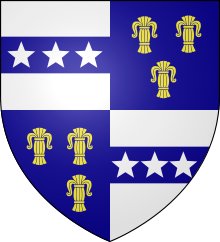

In 1399 Sir Adam Mure owned the castle and after his death it fell to his second son, while the first received Rowallan Castle. The lands of Limflare and Lowdoune Hill were included in the inheritance. The castle and baronate of Polkelly was mainly owned by the medieval Mure family , but Robert Mure died in 1511, leaving his daughter Margaret, Lady Polkelly , as sole heir . Margaret married Robert Cunningham of Cunninghamhead in March 1512. The stars of the Mures were thus added to the coat of arms of the Cunningham. After 50 or 60 years the Polkelly family sold Castle to Thomas Cochran of Kilmarnock and in 1699 it fell to his brother William . David , the 1st Earl of Glasgow , then bought the property and in the 1870s it belonged to James , Earl of Glasgow. In the 1860s, the ruins were described as "the strong house of Polkelly" and the remains were on the hillside north of Muiryet .

At the end of the 15th century, a mud from Polkelly was recorded as a royal administrator collecting royal rents in east central Scotland.

Lollards

Helen Chalmers , sister of Margaret Chalmers of Cessnock , was brought up for trial as a supporter of the Lollards who were promoting religious reform in Ayrshire. Helen was the wife of Robert Mure von Pokellie (Polkelly).

Moor of Machirnock (Glenouther)

Tensions arose between the Cunninghams and the Mures over grazing rights and other rights to the very large and valuable parish north of Polkelly, called "Machirnock" or "Maucharnock" (now "Glenouther"). A royal letter dated 1534 stated that the Cunninghams had no rights to the moor and stated that the "Souming" would be split between Polkelly Castle and Rowallan Castle. “Souming” was the number or proportion of cattle that each tenant was allowed to graze on the community property. In 1594, William Mure of Rowallan Castle complained about the excessive amount of cattle and geese that the Lord of Polkelly Castle grazed on the moor, although on May 20, 1593 he had received a warning from "Lawburrows". "Lawburrows" was a letter on behalf of the monarch and under his seal indicating that a certain person feared harm from another person and therefore that other person complained about it for "sufficient reason and with sufficient certainty" the complainant, for his part, is protected from possible attacks.

It is thought that these tensions did not develop earlier because Polkelly Castle, including the rights to the moor, was given to the younger sons of the Mures on the occasion of their marriage.

Map sources

Blau's map, which was created after Timothy Pont's survey in the early 17th century, shows a tower without any forests. Armstrong's 1775 map shows two buildings called "Pockelly," but none of them are depicted as a castle or a country house. Pokelly Hall is first shown on Thomson's 1832 map. Then the Ordnance Survey Map from 1890 shows "Pokelly Castle" in an enclosure near the Balgray Mill Burn and on a road system that connects to Gardrum Mill , Gainford , Crofthead and Fenwick . The name "Pathelly Hall" is sometimes used for Polkelly Hall in ancient sources.

Cleuche is in the Baronate “Powkellie” and now appears as “Clunch” in the Ordnance Survey cards. Dareloch , once recorded as “Darclavoch”, could be derived from “Dir-clach” (German: stony land). Drumboy was once called "Drumbuy" and previously belonged to the Baronate Strathannan in Lanarkshire .

King's kitchen

An old thatched farmhouse at the top of Stewarton on the B769 to Glasgow was called King's Kitchenhead but was later called Braehead. The story is told of a king, possibly James V , who stayed at this farmhouse on his way to judgment day after crossing Fenwick Moor . After recognizing her guest, the farmer's wife begged the king for the life of her husband, who was one of those over whom he was to sit in judgment. The others were hanged, but the king released the farmer's wife with the admonition to "be a better child". Another version of this legend adds the detail that there were 18 men in the Polkelly Castle prison and the king added that if this man were ever caught committing a crime again, all of the ancient women of Christianity together would not be able to remove him from the Save the hangman's noose. Polkelly's Gallows Hill was easy to see for a long time, as it was marked with a single pine tree .

Individual evidence

- ^ Archibald R. Adamson: Rambles Round Kilmarnock . T. Stevenson, Kilmarnock 1875, p. 124.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Gordon Ewart, Dennis Gallagher: A Palace fit for a Laird. In: Rowallan Castle - Archaeological and Research. Historic Scotland, 1998-2008, ISBN 978-1-84917-015-4 , p. 95.

- ↑ James Rollie: The Invasion of Ayrshire. A Background to the County Families . Famedram, 1980, p. 83.

- ^ Gordon Ewart, Dennis Gallagher: A Palace Fit for a Laird. In: Rowallan Castle - Archaeological and Research. Historic Scotland, 1998-2008, ISBN 978-1-84917-015-4 , p. 67.

- ^ Gordon Ewart, Dennis Gallagher: A Palace Fit for a Laird. In: Rowallan Castle - Archaeological and Research. Historic Scotland, 1998-2008, ISBN 978-1-84917-015-4 , p. 69.

- ^ Lainshaw Register of Sasines. P. 178.

- ↑ a b James D. Dobie, JS Dobie (Ed.): Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604-1608, with connotations and illustrative notices . John Tweed, Glasgow 1876, p. 362.

- ^ Gordon Ewart, Dennis Gallagher: A Palace Fit for a Laird. In: Rowallan Castle - Archaeological and Research. Historic Scotland, 1998-2008, ISBN 978-1-84917-015-4 , p. 98.

- ^ Archibald R. Adamson: Rambles Round Kilmarnock . T. Stevenson, Kilmarnock 1875, p. 145.

- ↑ James Paterson: History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton . Chapters V - III: Cunninghame . J. Stillie, Edinburgh 1863-1866, p. 243.

- ^ Margaret HB Sanderson: Ayrshire and the Reformation. People and Change 1490–1600 . Tuckwell Place, East Linton 1997, ISBN 1-898410-91-7 , p. 40.

- ^ S Words . Wikibooks. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ L Words . Wikibooks. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ↑ Timothy Pont, Joan Blaeu: Cuninghamia / ex schedis Timotheo Pont; Ioannis Blaeu. National Library of Scotland, accessed December 15, 2017 .

- ^ Andrew Armstrong: A New Map of Ayrshire (...). National Library of Scotland, accessed December 15, 2017 .

- ↑ John Thomson, William Johnson: Northern Part of Ayrshire. Southern Part. National Library of Scotland, accessed December 15, 2017 .

- ^ Dane Love: Ayrshire: Discovering a County . Fort Publishing, Ayr 2003, ISBN 0-9544461-1-9 , p. 103.

- ↑ James D. Dobie, JS Dobie (Ed.): Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604-1608, with connotations and illustrative notices . John Tweed, Glasgow 1876, p. 115.

- ↑ James D. Dobie, JS Dobie (Ed.): Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604-1608, with connotations and illustrative notices . John Tweed, Glasgow 1876, p. 131.

- ↑ James D. Dobie, JS Dobie (Ed.): Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604-1608, with connotations and illustrative notices . John Tweed, Glasgow 1876, p. 132.

- ^ Archibald R. Adamson: Rambles Round Kilmarnock . T. Stevenson, Kilmarnock 1875, p. 125.

- ↑ Dane Love: Legendary Ayrshire. Custom: folklore: tradition . Carn., Auchinleck 2009, ISBN 978-0-9518128-6-0 , p. 62.