Battle of Satala (297)

In the battle of Satala at the end of the 3rd century, the Romans under Caesar Galerius defeated a Sasanid army under their great king Narseh . In the peace of Nisibis the Sasanids had to make generous concessions, which only Shapur II could revise in the peace of 363 .

prehistory

See also: Roman-Persian Wars

After the end of the turmoil of the throne that broke out after the death of Bahram II , the Sasanid great king Narseh felt in a position to resume the great power policy towards Rome that his father Shapur I and his predecessor Ardaschir I had pursued. He found a favorable opportunity when he saw the main forces of the Emperor Diocletian bound in Egypt , where Domitius Domitianus had proclaimed himself anti -emperor. In autumn 296 he invaded Armenia and drove out the regent installed there by the Romans, Trdat III. Then he crossed the Tigris and attacked northern Roman Mesopotamia . The fact that there was also an incursion into Syria , as Theophanes or Johannes Zonaras later describe, is ruled out in current research. Diocletian instructed his Caesar Galerius to make the defense offensive to hold Narseh off, but without putting everything at risk until he could intervene with troops from Egypt himself.

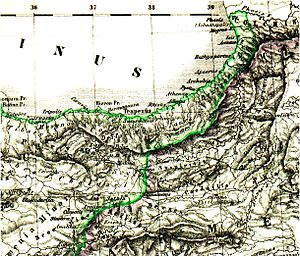

The first military confrontation occurred when Galerius crossed the Euphrates between Carrhae (now Harran) and Callinicum (now Ar-Raqqah) in late 296 or early 297 , but Caesar suffered a severe defeat and had to retreat to Syria. According to Roman sources, this was due to an action carried out too hastily and with too little force. When Diocletian arrived in Syria and found out about it, he let his Caesar feel his displeasure and also let him run beside his chariot in purple robes. Despite this gesture, which should probably be understood as humiliation (this interpretation is, however, controversial in research), Galerius got another chance. He reinforced his army with Gothic auxiliaries from the Danube region and in late summer 297 (or early 298) marched into Armenia, where Narseh had withdrawn to secure the conquered areas. Diocletian moved with a second army to Mesopotamia, on the one hand to bring the area back into Roman hands, on the other hand to cover the southern flank of Galerius.

course

The late antique authors Eutropius and Festus state that Galerius himself with some companions, dressed in peasant clothes, went to the camp of the great king near Satala (today near the village Sadak in the Turkish province of Gümüshane ) in order to spy on it. The location of the camp suggests that Narseh was planning another attack, this time in the direction of Cappadocia . The fact that Galerius, as part of the rulers' college, led such a dangerous mission is extremely doubtful or impossible (ancient authors like to describe the alleged heroic deeds of rulers). What is certain, however, is that Galerius attacked the completely unprepared Sasanian army by surprise and defeated it - although it is unclear whether there was any real battle or whether the Persians immediately fled in panic after conquering the camp. Narseh managed to escape with great difficulty, but had to leave behind his entire family, harem and a considerable part of the state treasury. This was the first time since the existence of the Sassanid Empire that one had to accept such a severe defeat against Rome. The Byzantine chroniclers Theophanes and Zonaras report that Galerius pursued Narseh as far as Persia, Johannes Malalas even writes as far as India, which, however, is a grotesque exaggeration.

Diocletian's decision to limit itself to what had been achieved and to forego further conquests may save the Sasanid Empire from further humiliation. Presumably, Diocletian also simply had the experiences from the campaign of the emperor Gordian III. before his eyes, who after a first victory in 243 had advanced deep into the Persian Empire and had died there. It is also conceivable that Diocletian did not want his Caesar to be too successful. In any case, Galerius broke off the pursuit and withdrew to Roman Mesopotamia, although he would certainly have been interested in repeating the triumphant march of Carus , who had pillaged the Persian capital Ctesiphon (before he then mysteriously found death in enemy territory) .

After the battle, Galerius was given permission to build a triumphal arch in Thessaloniki , the Galerius Arch . The highly prestigious title of Persicus maximus ("greatest Persian winner"), however, which he accepted in 298, he was apparently only allowed to include in his title after Diocletian had resigned in 305 and he himself became Augustus .

Effects

At the meeting in Nisibis (today Nusaybin ), which had meanwhile been conquered by Diocletian, the terms of peace were negotiated. Narseh, who sent his confidante Apharban to Nisibis as a negotiator, was anxious to negotiate the release of his relatives who had been brought to Daphne (a suburb of Antioch ) and a peace that was as favorable as possible for the Sassanid Empire. However, Galerius reacted furiously to the ambassador's words, who pleaded for equality and mutual recognition: The fate of Emperor Valerian, who was imprisoned in Persia and perished there, speaks a different language. However, he assured that the royal prisoners would be treated with honor. The result of the first negotiations was the sending of the magister memoriae Sicorius Probus to Narseh, who was in the media near the Asprudis river , to present him with the specific Roman peace conditions. The embassy is said to have been put on hold for a long time to demonstrate that the Sassanid Empire, despite its defeat, was still able to stand up to Rome. The peace of Nisibis that was then concluded was, however, in fact a dictated peace, in which the Romans were hardly willing to negotiate and which contained the germ of new conflicts.

literature

- Wilhelm Enßlin : Valerius Diocletianus. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume VII A, 2, Stuttgart 1948, Sp. 2419-2495.

- Wilhelm Enßlin: To the Ostpolitik of the Emperor Diocletian . Munich 1942.

- Wolfgang Kuhoff : Diocletian and the epoch of the tetrarchy: The Roman Empire between crisis management and rebuilding (284–313 AD) . Frankfurt / Main 2001.

- Engelbert Winter : The Sasanian-Roman peace treaties of the 3rd century AD - a contribution to the understanding of the foreign policy relations between the two great powers . Frankfurt / Main, Bern, New York, Paris 1988.

- Engelbert Winter, Beate Dignas: Rome and the Persian Empire. Two world powers between confrontation and coexistence . Berlin 2001.

Web links

- No direct information about the battle, but a graphic representation of the legionary camp near Satala and some photographs (PDF file; 1.34 MB)

- Course of the negotiations in Nisibis and on Asprudis (PDF file; 107 kB)

Remarks

- ↑ As Caesar , the lower emperor was referred to in the system of tetrarchy introduced by Diocletian .

- ↑ The elevation of Domitianus is also partly dated in the summer of 297. In this case, the usurpation would not have been the reason for the Persian attack, but (also) a reaction to the defeat of Galerius.