Senilia

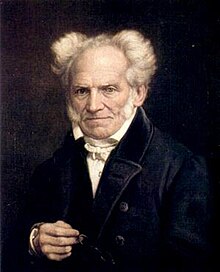

Senilia is the title of a collection of small wisdoms written by Arthur Schopenhauer that was published under the book title The Art of Getting Old . It contains the results of meditation as recorded by Schopenhauer in the last years of his life. In the 150 years that followed, a great deal of knowledge about aging was gained. However, the art of getting old - that is the (according to Schopenhauer) "brilliant" behavior of the spiritually and spiritually active person - is hardly survivable in Schopenhauer's estate.

Nevertheless, over two and a half millennia there have been countless findings of scientific and artistic provenance that characterize a conception of the art of growing old that is possible today. The art of growing old is revealed in their history.

Schopenhauer's forerunner

Schopenhauer's views on the two and a half thousand year old tradition of philosophical doctrines on aging are already set out in the Parerga and Paralipomena . The Senilia are in the tradition of Buddhism and the pre-Socratics. Of course there are references to Plato (or Socrates) and of course also to Roman philosophy, especially Cicero.

“In order to always have a safe compass at hand for orientation in life, and in order to always see it in the right light without ever getting mad, nothing is more suitable than to get into the habit of looking at this world as a place of penance, so to speak as a penal institution ... as the oldest philosophers called it and among the Christian fathers Origen pronounced it with praiseworthy boldness; - whichever view of the same finds its theoretical and objective justification, not only in my philosophy, but in the wisdom of all times, namely in Brahmanism , in Buddhaism , in Empedocles and Pythagoras ; as Cicero also points out that it was taught by ancient sages and during the instruction in the mysteries, ´that we were born to serve punishments because of certain mistakes committed in a previous life.´ "

Schopenhauer

Senilia

"This book is called Senilia". This is how the handwritten collection of short texts by Schopenhauer began in the years from April 1852 to 1860. Combined with the most varied of ideas, the thesis is presented that in old age people can largely leave the strivings of the will behind them and the imagination become completely dominant . “You just have to get old pretty, everything will be there”. The art of growing old is demonstrated with his meditations and the corresponding writings. It basically consists of how Schopenhauer behaves himself.

Christianity or Buddhism

As in many places in Schopenhauer's work, the Judeo-Christian tradition for a plausible interpretation of aging and the art of growing old is rejected in the Senilia.

"As long as you make the conditio sine qua non [indispensable condition] of every philosophy that it is tailored to Jewish theism , there is no understanding of nature, indeed no serious research into the truth."

Schopenhauer occasionally refers to himself as a Buddhist in order to explain himself to the subject of growing old and dying. In order to consider growing old, one must start from the basic requirement that souls are incarnated in order to learn how to grow old in the course of life - not from outside as learned content, but from within - as a "thing in itself".

The imperishable and non-teachable value of a person consists in his ability to objectify the will. To Schopenhauer it appears innate and cannot be conveyed through pedagogical guidance.

“Therefore, like our moral, so also our intellectual value does not come from outside in us, but emerges from the depths of our own being, and no Pestalozzian educational arts can form a thinking person from a born drip, never! he was born as a drip and must die as a drip. "

This view goes back to the Socratic concept of Maieutik (midwifery art), i.e. the art of the development of the fetus when it receives help from the birth canal with skillful manipulations to reach the light of day.

World and time

Any theory of aging must be placed in the context of being and time. Man can only grow old by entering temporality. Although his soul is not destroyed by death, it can only perfect itself in the course of its incarnation, ie within the "world".

“ The world is not made: for, as Okellos Lukanos says, it has always been; namely because time is conditioned by knowing beings, and consequently by the world , like the world by time . The world is not possible without time; but time is not without a world either. These two are therefore inseparable, and there is no more a time in which there was no world than a world which at no time would even be possible to even think. "

Will and imagination

Crucial for the art of getting old is the ability to break free from the service of will.

"One sees clearly in animals that their intellect is only active in the service of their will : with men it is, as a rule, not much different. One can see it in them too; yes, in some cases even that it never is acted differently, but was always directed only to the petty ends of life and the often so low and unworthy means of doing so. Whoever has a decided excess of intellect, beyond what is necessary for the service of the will, what excess then naturally get into a completely free activity that is not aroused by the will, nor that affects the purposes of the will, the result of which will be a purely objective apprehension of the world and things - such a person is a genius , and this is expressed in his face: less strong, however, any excess over the aforementioned poor measure. "

meditation

In Schopenhauer's view, a true philosopher is not only an academic, he is also always a practitioner of philosophy. He meditates in the spirit of Buddhist teachings and cares for himself; that is, he strives to become an “old” person through the practical exercise of his insights. It is about the philosophical wisdom that has been postulated over and over again from the pre-Socratics up to the time of Schopenhauer, without which recognition does not seem possible. Seen in this way, Schopenhauer's meditations on old age are to be placed in the great tradition of Platonism, the Stoa and the Christian practice of monastic life. The art of getting old is the art of being a practically meditating philosopher.

The late Greek philosopher Boethius has already described the Consolatio philosophiae , i.e. the consolation that consists in thinking about the essentials instead of being turned to the everyday needs of power, wealth and sexuality.

This is why the philosopher practices meditation:

“Anyone who experiences two or even three generations of the human race will have courage like the spectator of the performances of jugglers of all kinds in stalls, during the fair, when he remains seated and sees such a performance repeated two or three times in succession: the things they were only calculated for one idea and therefore have no effect after the deception and the novelty have disappeared. "

Exercise, sleep, nutrition

Schopenhauer occasionally gives practical tips on how best to behave in order to grow old in health. In any case, reaching a high biological age is a prerequisite for the perfection of the inner being.

“Sleep is the source of all health and the guardian of life. I still sleep my 8 hours, mostly without any interruption. You have to walk quickly for an hour and a half a day, taking the time away from sitting amusements; take a lot of cold bathing in summer; if you wake up at night, yes, nothing spared, or think anything interesting, just the blandest stuff with a lot of variety, but in good, correct Latin: that is my remedy. "

Life Science Findings

The age knowledge of the biological disciplines in the 20th century has enriched the art of growing old, especially in two areas:

- physical behavior (e.g. diet, exercise, home, etc.)

- Disease prophylaxis, i.e. concern for early diagnosis and avoidance of harmful influences.

Schopenhauer provides only relatively sparse information on this. The life sciences had made too little progress in the field of age research.

The basic theoretical research of aging has also made considerable progress - particularly through molecular biology.

Physical theology of aging

In Schopenhauer's view, the world did not come into being through the intellect of a personal God, to whom one would have to answer at the end of life. Rather, it is the will of the being itself that explains its aging.

“As easy as the physicotheological thought that it must be an intellect ( a mind ) who has modeled and ordered nature and appeals to the raw mind, it is fundamentally wrong: For the intellect is known to us only from animal nature, consequently a thoroughly secondary and subordinate principle of the world, and a product of late origin, can therefore never have been its condition: on the other hand, the will which fulfills everything and immediately announces itself in everyone, thereby designating it as its appearance, appears everywhere as the original . Hence all teleological facts can be explained by the will of the being itself in which they are found. ""

As we know today, sexual reproduction and individual death have been the promoters of development in life for about 800 million years. Bacteria (prokaryotes) reproduce largely identically; This means that the genome passes from the mother cell to the daughter cell in exactly the same way. With sexual reproduction (eukaryotes) this changes fundamentally: the haploid (simple) chromosome set of the father is attached to the homologous chromosome set of the mother, so that the dominant gene is used in the art of survival. In the phylogenesis of this new principle of multiplication, no act of creation is postulated.

At the same time as the arrangement of the chromosomes next to one another, telomeres and mesomers are formed. These are highly replicative sequences that exist hundreds of times at the ends and in the middle of each chromosome. With each cell division, the number of telomeres decreases, and when there are no more telomeres, the cell in question is no longer able to divide. In this way, individual death is directly linked to the sexuality of multiplication.

This achievement in the development of life is adequately explained by the successive mutations without having to assume an individual act of creation. In this respect, molecular genetics confirms Schopenhauer's basic approach.

Disease prophylaxis

The 20th / 21st In the 19th century, early diagnosis and prevention of the diseases of old age made decisive progress. First, the causative agents of the major infectious diseases were identified (tuberculosis, syphilis, plague, smallpox, etc.). The metabolic diseases - especially diabetes and hyperlipidemia - could be identified and z. T. be treated effectively. The countless allergies and malignancies were clarified. In recent times, even the genetically fixed malformations can be stopped early with some prospect and their progression can be alleviated.

Schopenhauer comments on this:

“The human lifespan is set in two places in the Old Testament ... at 70 years and, when it comes up, 80 years ... But it is still wrong and is merely the result of a crude and superficial understanding of daily experience. Because if the natural lifespan were 70 - 80, people would have to die between 70 and 80 years of age: But this is not the case at all: they die, like the younger ones, of diseases: the disease is essentially an abnormality: well this is not the natural ending. People only die between 90 and 100 years of age, but then as a rule, of old age, without agony, without rattling, without twitching, sometimes without turning pale; which is called euthanasia. "

Behavioral suggestions

One of the best-known authors of behavioral suggestions for reaching a high age - a certain precondition for getting old in the Schopenhauerian sense - is Manfred Köhnlechner . The suggestions range from countless dietary supplements and various cooking skills (especially the preparation of dishes with unsaturated fatty acids) to special body movement and meditative concentration.

Schopenhauer also had a small number of suggestions ready, which have already been quoted in the chapter on sleep and exercise.

A special approach is currently the preservation of sexual functions. In addition to hormone substitution ( estrogen in women in the period of the beginning postmenopause and testosterone in men in the period of declining libido). In both cases, special risks for malignant diseases are discussed. Estrogen substitution requires particularly strict control of breast cancer. Testosterone administration requires particularly close monitoring of prostate cancer.

For Schopenhauer, the topics of hormone substitution were unknown. Only procreation is discussed as a counterpoint in the discussion of dying:

“Plato (at the entrance to the republic) estimates that old age is much more correct, as long as the sex drive, which up until then has been constantly worrying us, is finally rid of. It could even be said that the manifold and endless crickets which the sexual instinct produces, and the affects arising from them, maintain a constant, mild madness in man as long as he is under the influence of that instinct or that devil with which he is always possessed. stands."

For Schopenhauer, the art of getting old is not the art of living as long as possible, but the art of becoming an old soul in the sense of the Buddhist theory of reincarnation. Only a long life offers better chances to qualify in the art of becoming an old soul. Long life is, so to speak, a conditio sine qua non (indispensable condition) for the art of growing old.

And it is precisely in this point that the age research of the 20th / 21st Century far beyond Schopenhauer. Testosterone is not just a sex hormone, it has an anabolic effect; that is, muscles, bones and tendons are formed more abundantly, so that the atrophies of old age are prevented. However, the hope of increasing life expectancy through hormone substitution has not been confirmed.

Estrogen substitution is also effective against osteoporosis, arteriosclerosis and dementia. The cliché of decreasing sexual harassment, which has been valid for thousands of years, needs to be revised from the point of view of hormone substitution.

Psychosocial Aging

Schopenhauer paid surprisingly little attention to the psychosocial factors of aging. Schopenhauer's biography shows a great reluctance to socialize. The attempt to practice meditation in philosophical practice has kept the so-called pessimists far too far away from cheerful company.

On the other hand, it is now well known that a positive attitude towards the content of life in society has a life-prolonging effect. Disengagement , i.e. a negative attitude towards the social environment, is associated with lower life expectancy.

The involution of language with its organic and social components has also become a decisive factor in the study of aging in the post-Schopenhauer period. Schopenhauer's reluctance towards society was thwarted primarily by the formation of societies of older men - and later also of mature women.

Schopenhauer sees a significant contribution to the art of growing old only in music:

“Now, furthermore, in the entire ripen voices that produce harmony, between the bass and the leading voice singing the melody, I recognize the entire sequence of ideas in which the will is objectified. Those closer to the bass are the lower of those levels, the still inorganic, but already expressed bodies: the higher ones represent to me the world of plants and animals. [...] Finally, in the melody , in the high-pitched, singing main voice that guides the whole thing and unrestricted arbitrariness in the uninterrupted, meaningful context of a thought from beginning to end and representing a whole, I recognize the highest level of objectivation of the will , the level-headed life and striving of man. "

In a study from the eighties of the 20th century, men aged 70 to 80 were supposed to be in a simulated environment from 1959 and talk to each other about nothing but positive things in life from that time. As a result, it was found that the test subjects were able to improve their eyesight and joint mobility.

On the other hand, the mistrust of one's own abilities was examined in relation to actual motor performance. The results show the influence of distrust in the sense of Schopenhauer's pessimism.

Conclusion

Schopenhauer sees his meditations on the art of growing old as a continuation of a long series of philosophical and theological teachings from antiquity, the Middle Ages and modern times. He combines his theory with a practical way of life in the sense of the art of growing old. His connection to East Asian teachings refers to the art of mental aging. In addition to sleep, sport and hygiene, the objectification of the will to the world is crucial. Music should offer special help here.

The biosciences of the 20th century mainly developed pharmacological approaches that go far beyond Schopenhauer, but by no means relativize the approach of a philosophical practice. Schopenhauer's pessimism can only be overcome from a better understanding of Hindu ideas of the soul. Aging of the soul is the goal of all higher life and leads to the perfection for a later life.

literature

- Anders, Jennifer; Ulrike Dapp, Susann Laub and Wolfgang von Renteln-Kruse: Influence of the risk of falling and the fear of falling on the mobility of independently living older people at the transition to frailty. Screening results for municipal fall prevention . In: Journal of Gerontology and Geriatrics , 2007, Volume 40, Number 4, Pages 255-267

- Belke, Horst: Ludlamshöhle [Vienna] . In: Wulf Wülfing, Karin Bruns, Rolf Parr (eds.): Handbook of literary-cultural associations, groups and associations 1825–1933 . Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 1998, pp. 311-320 (Repertories for the history of German literature. Ed. Paul Raabe. Volume 18).

- Birnbacher, Dieter: Schopenhauer . Reclam, Basic Knowledge Philosophy, 2010.

- Boberski, Heiner; Peter Gnaiger, Martin Haidinger, Thomas Schaller, Robert Weichinger: Powerful - Male - Mysterious. Secret societies in Austria . Salzburg: Ecowin Verlag 2005.

- Cumming, E / WE Henry: A formal statement of disengagement theory . In: Growing old: The process of disengagement . Basic Books, New York 1961.

- Goethe, Johann W. von: Poetry and Truth . Stl. Works ed. Trunz, Erich Volume 9, p. 531 f. Munich 1998

- Hübscher, Arthur (ed.): Arthur Schopenhauer: Collected letters . Bonn 1978

- Langer, Ellen: Turn back the clock ?: Grow old healthily through the beneficial effects of attention . Munich: Jungermann 2011

- Maas, Michael: The Schlaraffia Men's Association 1914-1937 . Bad Mergentheim 2006.

- Motel-Klingebiel, A., S. Wurm and C. Tesch-Römer (eds.): Aging in change. Findings of the German Age Survey (DEAS) . Kohlhammer, 2010

- Schwartz, FW: The Public Health Book . Elsevier, Urban & Fischer Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-437-22260-0 , p. 163.

- Volpi, Franco (Ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of getting old . Munich: Beck 2009

- Witzany, Guenther: The viral origins of telomeres, telomerases and their important role in eukaryogenesis and genome maintenance . Biosemiotics 2008, 1: 191-206.

- Ziegler, Ernst (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of staying alive . Munich: Beck 2011

- Ziegler, Ernst (ed.): Arthur Schopenhauer: About death . Munich: Beck 2010.

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Volpi, Franco (Ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of getting old. Munich: Beck 2009

- ↑ cf. Birnbacher, Dieter: Schopenhauer. Reclam, Basic Knowledge Philosophy, 2010

- ↑ Hübscher, Artur (ed.): Arthur Schopenhauer: Complete works. Vol. 6, p. 231

- ↑ a b Volpi, Franco (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of getting old. Munich: Beck 2009, p. 22

- ↑ a b Hübscher, Arthur (ed.): Arthur Schopenhauer: Collected letters. Bonn 1978, p. 236

- ↑ Ziegler, Ernst (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of staying alive. Munich: Beck 2011, p. 33

- ↑ Plato, Theaetetus 148e – 151d. See Theaitetos 161e, where the term maieutike techne is used.

- ↑ Volpi, Franco (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of getting old. Munich: Beck 2009, p. 22f.

- ↑ Volpi, Franco (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of getting old. Munich: Beck 2009, p. 11

- ↑ a b Volpi, Franco (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of getting old. Munich: Beck 2009, p. 25

- ↑ Ziegler, Ernst (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of staying alive. Munich: Beck 2011, p. 20

- ↑ cf. Motel-Klingebiel, A., S. Wurm and C. Tesch-Römer (eds.): Aging in change. Findings of the German Age Survey (DEAS). Kohlhammer, 2010

- ^ Witzany, Guenther, The viral origins of telomeres, telomerases and their important role in eukaryogenesis and genome maintenance. Biosemiotics 2008, 1: 191-206

- ↑ Ziegler, Ernst (ed.): Artur Schopenhauer: The art of staying alive. Munich: Beck 2011, p. 62

- ↑ Hübscher, Arthur (ed.): Arthur Schopenhauer: Collected letters. Bonn 1978, p. 379

- ↑ Cumming, E / WE Henry: A formal statement of disengagement theory. In: Growing old: The process of disengagement. Basic Books, New York 1961

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer: The world as will and idea. Cologne 1997, first volume, §. 52.

- ↑ Langer, Ellen: Turn back the clock ?: Growing old healthily through the beneficial effects of attention. Munich: Jungermann 2011

- ↑ Anders, Jennifer; Ulrike Dapp, Susann Laub and Wolfgang von Renteln-Kruse: Influence of the risk of falling and the fear of falling on the mobility of independently living older people at the transition to frailty. Screening results for municipal fall prevention. In: Journal of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 2007, Volume 40, Number 4, Pages 255-267