Trade-off theory of capital structure

The capital structure trade-off theory is that companies choose their leverage to maximize benefits and minimize costs .

General

Their designation goes back to an exchange relationship between at least two contracting parties ( English trade-off , "weigh up"). The classic version of the hypothesis goes back to Kraus and Litzenberger, who observed a balance between the risk of a loss of welfare due to the threat of bankruptcy and the tax advantages of debt capital . Agency costs are often included in this balance.

theory

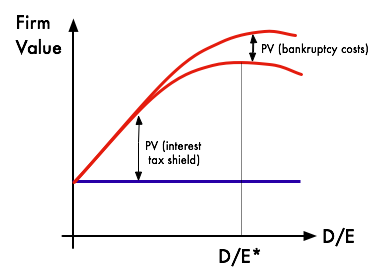

In the trade-off theory, debt and equity financing are calculated in such a way that the present value of the tax shield is as large as possible and the present value of the costs of "financial distress" is as low as possible. This calculation then results in an optimal leverage ratio ( debt / equity ) for each company , which maximizes goodwill . This results from the value of a fully equity-financed company plus the present value of the tax shield , minus the present value of the financial distress costs:

Wert eines komplett eigenkapitalfinanzierten Unternehmens + BW - Kosten vom Financial Distress = Firmenwert

The marginal benefits of debt financing decrease, while the marginal costs increase as more debt is borrowed. Companies therefore pay attention to an optimal trade-off when deciding whether equity or debt capital should be used for financing .

The theory thus contradicts the Modigliani-Miller theorem , which postulates that the capital structure of a company is irrelevant to its value. However, Modigliani-Miller also require frictionless markets.

In addition, the trade-off theory is often seen as a competitor to the pecking order theory , which states that companies prefer internal financing over debt over equity.

Empirical Findings

The empirical relevance of the trade-off theory has often been questioned. Miller, for example, compared this “balancing” with the horse and rabbit proportion in a stew consisting of a horse and a rabbit.

Since taxes are usually high and above all safe, bankruptcies are rare and, according to Miller, are associated with little welfare loss ( English deadweight losses ), the leverage effect of the companies observed in reality should be significantly greater.

Eugene Fama and French as well as Myers and Shyam-Sunder were also able to show that pecking order theory , which postulates a certain order of funding, can explain the data much better than the static trade-off theory.

Ivo Welch showed that, over a long time horizon, share price effects are more important in explaining the level of indebtedness than the proxies identified by the trade-off theory (“Tax Shield” and “Financial Distress”).

In addition, the trade-off theory fails with small businesses that have poor access to the capital market . Often these companies are denied access to the public debt capital market ( bonds ), and they have to fall back on, usually significantly more expensive, debt capital from financial intermediaries ( credit institutions ). Due to this supply-side restriction, an optimal debt level cannot be achieved.

Despite such criticism, trade-off theory is the dominant and most widely taught theory of corporate capital structure. In addition, dynamic versions of the model offer sufficient flexibility to be brought into line with the real data and are difficult to refute empirically.

Individual evidence

- ^ Alan Kraus, Robert H. Litzenberger: A State-Preference Model of Optimal Financial Leverage . In: The Journal of Finance . tape 28 , no. 4 , September 1, 1973, ISSN 1540-6261 , p. 911-922 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1540-6261.1973.tb01415.x ( wiley.com [accessed August 14, 2017]).

- ^ Milton Harris, Artur Raviv: The Theory of Capital Structure . In: The Journal of Finance . tape 46 , no. 1 , March 1, 1991, ISSN 1540-6261 , pp. 297-355 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1540-6261.1991.tb03753.x ( wiley.com [accessed August 15, 2017]).

- ^ Merton H. Miller: Debt and Taxes * . In: The Journal of Finance . tape 32 , no. 2 , May 1, 1977, ISSN 1540-6261 , pp. 261-275 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1540-6261.1977.tb03267.x ( wiley.com [accessed August 15, 2017]).

- ^ Eugene F. Fama, Kenneth R. French: Testing Trade-Off and Pecking Order Predictions About Dividends and Debt . In: The Review of Financial Studies . tape 15 , no. 1 , January 1, 2002, ISSN 0893-9454 , p. 1–33 , doi : 10.1093 / rfs / 15.1.1 ( oup.com [accessed August 15, 2017]).

- ↑ Lakshmi Shyam-Sunder, Stewart C. Myers: Testing static tradeoff against pecking order models of capital structure . In: Journal of Financial Economics . tape 51 , no. 2 , p. 219-244 , doi : 10.1016 / s0304-405x (98) 00051-8 ( elsevier.com [accessed August 15, 2017]).

- ^ Ivo Welch: Capital Structure and Stock Returns . In: Journal of Political Economy . tape 112 , no. 1 , February 1, 2004, ISSN 0022-3808 , p. 106-132 , doi : 10.1086 / 379933 ( uchicago.edu [accessed August 15, 2017]).

- ↑ Michael Faulkender, Mitchell A. Petersen: Does the Source of Capital Affect Capital Structure? In: Review of Financial Studies . tape 19 , no. 1 , March 1, 2006, ISSN 0893-9454 , p. 45-79 , doi : 10.1093 / rfs / hhj003 ( oup.com [accessed August 15, 2017]).