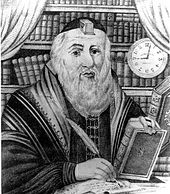

Gaon of Vilna

Elijah Ben Salomon Salman , called the Gaon of Vilna or also ha-Gaon he-Hasid , (born April 23, 1720 in Selez, Poland-Lithuania near Brest ; died October 9, 1797 in Vilna , Russian Empire ) was a versatile Jewish scholar who was highly valued during his lifetime. He is considered to be the epitome of Ashkenazi Judaism with Lithuanian characteristics. His commentaries on the Torah and Talmud , which dealt with a wide range of religious and social issues, are now standard works of Jewish scholarship.

Life

As the son of a respected rabbi family, Elijah ben Salomon enjoyed extensive training from an early age. After six months of studying the Talmud in Kėdainiai , he devoted himself to self-study in Vilnius, including Kabbalah and numerous scientific issues. After five years of wandering through Poland and Germany, he returned to Vilnius in 1745, which was then a center of Jewish learning. Thanks to his extensive knowledge, he soon acquired a good reputation among scholars as well as among the people, also thanks to his ascetic way of life. He was given the title of Gaon , the "Wise".

Until about 1760 he studied and worked very withdrawn. He was known for his humility and generosity. From 1760 he began teaching students in private meetings. The most famous ambassador of his teachings was Rabbi Chaim of Voloshin , who founded the famous yeshiva of Voloshin after the death of the Gaon . It remains unclear what prompted Elia Gaon to break off his emigration to the Holy Land after a few months in 1783 and return to Vilnius.

The Gaon was a staunch advocate of Orthodox teaching, which gave priority to the literal, rational interpretation of the Torah and the laws of Halacha . He rejected the newly developed teaching of Hasidism , which particularly emphasized feeling and mysticism ( Misnagdim ). He considered them a tendency hostile to Torah learning and had the ban pronounced on the Hasidim in 1772 and 1782 , which all Lithuanian congregations joined. Attempts by Schneor Salman von Ljadi , the founder of the Lubavitch Hasidim , to meet with him for a discussion about the legitimacy of the Hasidic movement, he rejected. He also banned the consumption of meat from Hasidic Schächtern was geschächtet, marriages prohibited between Hasidic Jews and members of his own community and had 1794 the book Zawaat Ribasch ( "Testament of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov ," the founder of Hasidism) burn in public in Vilnius. After the death of Elijah Ben Solomon in 1797, serious clashes broke out in Vilnius between supporters of the two directions, which resulted in the establishment of their own communities of Hasidim.

Elijah Ben Salomon Salman had a truly phenomenal scholarship. His knowledge was not limited to Judaic tradition. He spoke at least ten languages and was at home in math and other sciences. The Gaon saw science as essential to understanding the Torah. However , he rejected any change in the Halacha that the early Haskala aimed at.

family

The parents of Elijah Ben Salomon Salman (or Zalmen) were Shlomo Zalmen (1695-1758) and his wife Treina, daughter of Rabbi Meir from Selez (also Seltz, Belarus).

His first wife Khana (died 1782) was the daughter of the Keidan merchant Yehudah Leib , whom he married at the age of 18. She raised eight children together. These were the eldest daughter (1741–1756, name unknown), daughter Khiena (1748–1836), daughter Peisa-Bassia (1750–), daughter (1752-, name unknown), son Shlomo-Zalmen Vilner (1758–1780) , Son Yehudah Leib Vilner (1764–1816), son Avraham Vilner (1765–1808) and daughter Tauba (1768–1812). The sons in turn became rabbis and the daughters married rabbis.

Adult grandchildren of the Gaon of Vilna are known by name of 43, great-grandchildren (born around 1800) 143. This generation became part of the Jewish population boom, in which the number of descendants per generation multiplied. The seventh generation of descendants of the Gaon, born around 1900, already numbered around 13,000 people. His second wife was Gittel, the daughter of Meir Luntz. No further children were born from this marriage.

In the succession of the Vilna Gaon there was an upswing in the traditional rabbinical school system in Poland-Lithuania and centers for the study of the Talmud, the great yeshivot like that of Voloshin, which became a bastion against the incipient Haskala and assimilation.

In the memorial stone of the Gaon of Vilna, believing Jews put a note with requests to God.

Commemoration

The Vilnius Gaon State Jewish Museum in Vilnius, founded in 1989, bears his name.

literature

- Isak Unna: Rabbi Elia, the Gaon of Vilna and his time. (= Jüdische Volksbücherei. Volume 13) Jüdischer Volksschriftenverlag, Frankfurt am Main around 1921, OCLC 422784 .

- Salomon Schechter, Ignaz Kaufmann: Rabbi Eliah Wilna Gaon. Oesterreichische Wochenschrift, Vienna 1891, OCLC 741251285 .

- Martin Schulze Wessel : Vilnius. History and memory of a city between cultures. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-593-41014-2 , p. 75. ( Monument )

- Ben-Tsiyon Klibansky: Vilna. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 6: Ta-Z. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2015, ISBN 978-3-476-02506-7 , pp. 408-414.

Web links

- A precious legacy - works of Vilner Gaon Elijahu b. Zalman in the Martynas Mazvydas National Library of Lithuania (February 19, 2012 memento in the Internet Archive )

- Gaon on juden-in-europa.de

Individual evidence

- Jump up ↑ Immanuel Etkes: The Gaon of Vilna - The Man and His Image , University of California Press, 2002, ISBN 0-520-22394-2 , pp. 11 and 12

- ↑ Note: The title Hasid has nothing to do with Hasidim , but was in use even before the emergence of Hasidism and referred to a person who is far above other people in terms of the quality and intensity of their worship of God and their degree of spiritual exaltation .

- ↑ a b c d e Elijah Ben Salomon Salman on maschiach.de, accessed on May 12, 2014.

- ↑ Howard M. Sachar: Hasidism ; in Frederick R. Lachmann: The Jewish Religion , Aloys Henn Verlag, Kastellaun, 1977, ISBN 3-450-11907-9 , p. 151

- ^ Eliyahu Stern: The Genius - Elijah of Vilna and the Making of Modern Judaism , Yale University Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0-300-17930-9 , p. 15

- ↑ Chaim Freedman: Eliyahu's Branches: The Descendants of the Vilna Gaon (Of Blessed and Saintly Memory) and His Family. Avotaynu, Teaneck, NJ 1997, p. 8. ISBN 1-886223-06-8 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gaon of Vilna |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Salman, Elijah Ben Salomon; Zalman, Eliyahu ben Shelomoh |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Rabbi and Scholar |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 23, 1720 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Selez near Hrodna , Belarus |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 9, 1797 |

| Place of death | Vilnius , Lithuania |