Washington Irving Bishop

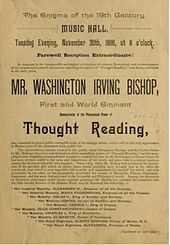

Washington Irving Bishop (* 1856 ; † May 12 or 13, 1889 in New York City ) was an American mentalist and mind reader .

Life

Washington Irving Bishop was a godchild of Washington Irving and the son of a medium . He grew up in New York City, where he attended a Jesuit school. After that he worked first in another profession and then as an assistant and finally as manager of Anna Eva Fay , who allegedly demonstrated spiritualistic phenomena. But they parted in a dispute and Bishop revealed some of their tricks in newspaper articles and at stage performances. He assisted John Randall Brown for a year , after which he went into business for himself as a mind reader or revelator of spiritualistic tricks and moved to England. His demonstrations, in which he demonstrated thought and muscle reading experiments, were very successful. He usually put his presentations in the context of solving a fictional crime.

Bishop returned to the United States around 1886. One of his bravery pieces now was driving blindly in a carriage past several blocks to find a hidden brooch. A man in the audience sat next to him on the driver's seat during this experiment, holding his hand so that Bishop's muscle-reading ability would be able to pinpoint the right direction.

death

Washington Irving Bishop had fallen into a coma several times , but always woke up after a few days. Fearing that under such circumstances he would one day be considered dead, he always carried a slip of paper with him explaining this peculiarity of his nature and asking not to undergo dangerous treatment or worse such as an autopsy, but in the case of one Faints quietly waiting for his awakening. When he again passed out twice during a performance at the Lambs' Club in New York after he had previously exhibited conspicuous pulse activity, this note was not read, instead three doctors proceeded to do the autopsy without much delay - perhaps also because Bishop a short while before he had joked that after his death his mind-reading organ would be found safely inside him. Since it was assumed that the cause of death must be found in Bishop's head, according to some sources, doctors rushed to saw open the skull and remove the brain before it had cooled down. According to a report in the New York Times in 1892, the autopsy took place on May 13, 1889 and the usual order of organs was followed during the examination.

Bishop's mother Eleanor filed a lawsuit against Dr. John Arthur Irwin, Frank Ferguson and Irwan H. Hance and showed that in 1873 their son had been unconscious for twelve days before he came to. However, the doctors were eventually acquitted, as it could not be clearly established whether Washington Irving Bishop had died as a result of the autopsy or had previously died. A second autopsy, which was carried out days after his death, was unsuccessful, but at least Bishop's brain was found in his chest, which his wife Mabel had allegedly missed after the first autopsy.

A dispute arose over Bishop's legacy. In his will he bequeathed his property to his daughter Helen Georgina Mack, the administrator of the estate was his divorced wife Ellen.

literature

- Eleanor Fletcher Bishop: A Mother's Life Dedicated and an Appeal for Justice to All Brother Masons and the General Public. A Synopsis of the Butchery of the Late Sir Washington Irving Bishop . Philadelphia 1890 (For the rest of her life she tried to hold doctors accountable; among other things, she distributed pictures showing her son lying in a coffin with his skull cut open.).

- Trevor H. Hall: The strange case of Edmund Gurney . Duckworth, London 1980, ISBN 0-7156-1154-2 , pp. 80-87 (unchanged reprint of the London 1964 edition).

- Ricky Jay: Learned pigs and fireproof women .

- German: Sauschlau and fireproof. People, animals, show business sensations. Stone eaters, fire kings, mind readers, escape artists . Huber, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-921785-50-2 (therein: A few words about death and show business. Washington Irving Bishop, J. Randall Brown and the origins of modern mind reading . Pp. 175–220)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c query.nytimes.com

- ↑ podcast.de

- ↑ a b magictricks.com

- ↑ query.nytimes.com

- ↑ deancarnegie.blogspot.com

- ↑ query.nytimes.com

- ↑ Fred Nadis: Wonder Shows. Performing Science, Magic, and Religion in America. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick NJ et al. 2005, ISBN 0-8135-3515-8 , p. 145.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bishop, Washington Irving |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American mentalist and mind reader |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1856 |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 12, 1889 or May 13, 1889 |

| Place of death | New York City |