When my soul is in you, my light, how can I live?

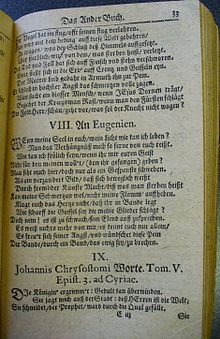

When my soul is in you, my light, how can I live? is a sonnet by Andreas Gryphius . Gryphius published it for the first time in 1650 in Frankfurt am Main in his sonnet collection “Das Ander Buch” , the eighth of 50 sonnets. There it bears the heading "To Eugenien" and is one of the Eugenien poems .

Origin and tradition

According to most researchers, "Eugenie" - a fictional, "poetic" name - hides Elisabeth Schönborner, the daughter of Gryphius' patron Georg Schönborner (1579–1637) on his estate near Freystadt in Lower Silesia . Gryphius raised Schönborner's sons there from 1636 to 1638 before going to the University of Leiden to study . The first two Eugenien sonnets, “ Beautiful is a beautiful body, which everyone's lips praise ” and “ What else do you wonder, you rose of the virgins ”, printed in 1637, come from this time close to Elisabeth. “If my soul is in you, my light, how can I live?” On the other hand, the fourth and last Eugenien sonnet that Gryphius himself published, thirteen years after the first two, was written in Leiden, far from Elisabeth and his Silesian homeland or on his major educational and study trip that followed in 1644.

"If my soul is in you, my light, how can I live?" Was reprinted in Gryphius' lifetime in 1657 and 1663. Marian Szyrocki reprinted the version from 1650 in 1963 in Volume 1 of a complete edition of the German-language works for which he and Hugh Powell were responsible, the last 1663 edition among others Thomas Borgstedt 2012. The following text comes from Borgstedt's edition.

text

To Eugenia.

If my soul is in you / my light how can I live?

Now fatality tears me so far away from you.

How can I be merry / if you don't want to give me your spirit

for mine / (whom you have captured)?

You can only see me hovering as a ghost.

As an enchanted image / that

knows itself to be movable. Power through foreign arts / that is what one means to die

Can my melt / not lift my flame. Doesn't the heart complain

/ that you put in bonds

How sharp are the scourge that strikes my gliders?

But no! it is too weak / misery to speak out.

It no longer knows anything about me / it only knows you alone /

it rejoices in its fear / and desires the pain of

the bond / to break through a bond / that is eternal /.

interpretation

Interpretations of the poem were mainly given by Dieter Arendt, Tomas Borgstedt and Andreas Solbach. Arendt emphasizes the biographical moments in the poem, Borgstedt and Solbach are critical of this.

Like most of Gryphius' sonnets, the poem is written in Alexandrians . The rhyme scheme is “abba abba” for the quartets and “ccd eed” for the trios . The verses with the “a” and “d” rhymes are thirteen syllable, the rhymes are feminine , the verses with the “b”, “c” and “e” rhymes are twelve syllable, therefore here according to the edition by Borgstedt indented, the rhymes masculine .

The first quartet laments the distance and the pain of separation. The resulting loss of one's own soul while staying with the beloved is a common concept in love poetry of neo-Latin descent. For Arendt, the second quartet, in which the lyrical ego only hovers as “a ghost”, is an indication of a life-threatening illness in the poet, which other poems also speak of. Borgstedt considers this reading to be incorrect. Arendt overlooks the underlying motive of the "deadly" loss of soul in love, which has nothing to do with a real experience of illness. The following verses 6 and 7 condense the Petrarchist elements. The lover is "an enchanted picture [...] / power through foreign arts". Even death can quench its pain, but cannot quench the "flame" of its love. The first trio formulates an unspeakable topos . The heart is no longer able to complain: "It is too weak / to express its misery" (v. 11).

The last trio leads to the desire for a "band / that is eternal" (verse 14). According to Arendt, it brings a paradoxical punch line: “The sick heart, which detaches itself from the local ego, rejoices in its fear of death, because with death the bonds of world and love pain are loosened and only then is the supernatural eternal Band. “Borgstedt and Solbach interpret closer to the text. According to Borgstedt, the punch line forms a "well-known, but at the same time ambivalent concetto : the Petrarkist love ties are here ingeniously transferred into the bond of marriage on the one hand, but on the other hand this 'eternal bond' is equally related to the Christian belief in God." Similar to Solbach: Should with the eternal bond “if a concrete and real marriage were meant, this would be a clear break with the Petrarkist convention; but it cannot be assumed. At most Gryphius plays with such an idea, which, however, pales behind the platonic idea of a community of souls in the hereafter. So we see [...] here a return to a de-individualizing Petrarkism, which at most reveals hidden and purposefully blurred references to the concrete historical addressee. "

literature

- Dieter Arendt: Andreas Gryphius' Eugenien-Gedichte . In: Journal for German Philology . tape 87 , no. 2 , 1968, p. 161-179 .

- Ralf Georg Bogner: Life. In: Nicola Kaminski, Robert Schütze (ed.): Gryphius manual. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-022943-1 , pp. 1–18.

- Thomas Borgstedt: Topic of the sonnet. Generic theory and history. Max Niemeyer Verlag , Tübingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-484-36638-1 .

- Thomas Borgstedt (Ed.): Andreas Gryphius. Poems. (= Reclams Universal Library . No. 18561) Reclam-Verlag , Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-15-018561-2 .

- Andreas Solbach: Gryphius and love. The poeta as amator and dux in the Eugenia sonnets. In: Marie-Thérèse Mourey (ed.): La Poésie d'Andreas Gryphius. Center d'études germaniques interculturelles de Lorraine, Nancy 2012, pp. 35–46.

- Marian Szyrocki (Ed.): Andreas Gryphius. Sonnets. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1963.

References and comments

- ↑ Arendt 1968, p. 166.

- ↑ Bogner 2016, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ The picture comes from a 1658 title edition of the 1657 edition.

- ↑ Borgstedt 2012, pp. 40–41. The 1657 text differs from the 1663 text apart from orthographically only the - probably printed - beginning of verse 8 "Kan Meine Schertzen wol".

- ↑ Dieter Arendt (1922–2015) was Professor of German Literature at the Justus Liebig University in Giessen . Internet source.

- ↑ Thomas Borgstedt is a Germanist and has been President of the International Andreas Gryphius Society since 2002 .

- ↑ Andreas Solbach has been Professor of Modern German Literature at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz since 1999 . Internet source .

- ↑ Borgstedt 2009, p. 340.

- ↑ Borgstedt 2009, p. 340 note 166.

- ↑ Solbach 2012, p. 46.

- ↑ Arendt 1968, p. 174.

- ↑ Borgstedt 2009, p. 340.

- ↑ Solbach 2012, p. 46.