Tenon connection

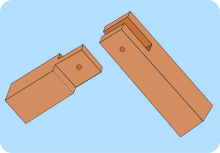

A mortise and tenon joint , and tenon joint , is a wood joint in joinery and carpentry . It consists of a tenon , the tenon hole or slot and, if necessary, further fastening means.

Basics

Tenons are among the links , so serve to connect two pieces of wood that meet, generally in a T-shape or as a corner connection (L-shape).

Square tenons and round tenons

There are two basic forms, the square tenon (connections with slot and tenon) and the round tenon .

The tenon connection with angular tenons is made by cutting or chiselling a rectangular hole (slot) in one wooden part and cutting a corresponding projection (tenon) in the other. Tenon width is generally 1 / 3 the thickness of the wood stronger timber. The slot is always rectangular in the direction of the grain so as not to weaken the perforated wood too much. The main advantage of the square tenon is that it prevents the wood from turning (or it tightens as the wood works), the tenon is quite simple to design, but the slot is complex. In general, the tenon is first made, marked on the fret, and then the hole is made so that the fit can still be checked.

The round tenon is round, with it the tenon hole can be drilled, but the tenon formation is more complex. Most of the time, the tenon is left slightly edged, as is the case with handcrafted wooden nails and dowels , so that the tenon wedges firmly. It is less used in carpentry and joinery, but in equipment and toolmaking.

Today, however, the mixed form of the two is common, because the mortise is made with a drill and milling cutter , and then also has round corners for slots.

In addition, numerous more or less complicated profile connections are also possible.

Full spigot and blind spigot

In general , the mortise penetrates the wood completely (full tenon, jack or collar pin ), the head of the mortised timber is flush with the back of the collar. This connection is less complex, but looks unattractive and is possibly also exposed to the weather.

If you want to avoid this, you use a blind plug , the hole of which does not fully penetrate the wood. The disadvantage is - in traditional manual work - the much more complex production, the preparation of the bottom of the hole is laborious, and the connection is "blind", so it cannot be checked for pass afterwards. With the use of the router for the tenon hole and precise numerical production, production is simplified, and is no longer a problem today, so that it has largely replaced the full tenon. The tenon length then corresponds approximately to the tenon width, not more than half of the mortised wood, and with some connections significantly less.

In addition, the tenon can also pierce the fret and protrude on the back: At the extended end, either another timber connection can be made (e.g. as a double tenon for a third timber), or insurance.

Joinery aids

If the pin is not exclusively subjected to pressure or if it is otherwise prohibited, it is generally drilled from the third level and pinned, continuously, on both sides, or only from one (the non-visible side), which is then called the flange side becomes. The nail is cut to length flush, but can also be done with decorative nails, where the head and piercing point of the nail create a picturesque joining image ( decorative nail ). In general, one nail is sufficient for corner connections (e.g. the frames of a window sash), two that are diagonally offset, four, five in a cube pattern, and other things. In addition, you can also roughly fix it with iron nails, or screw it with hinge screws on one side, or with threaded rods . Drilled tenons can also be made with staggered holes (inclined or staggered drilling before joining) and are subject to tensile stress when the nail is hammered in.

With a continuous mortise, the tenons can also be wedged from the back and are then called dovetail joints . These are often used on the crossbars of traditionally manufactured panel doors , as this type of connection provides a little more resistance to the sagging of the door leaf .

In addition, additional securing is possible with staples and numerous other metal connecting elements , or with intermediate sleeves made of plastic.

Pins that are manufactured separately and embedded in both elements to be connected are also called dowels .

Forms of cone formation

Axillary pin

The axillary cones or stepped cones

Fork pins, slotted pins, jerk pins

This fork, slot or shear pin connection is made by cutting an upwardly open mortise at the end of one part that mates with a tenon cut centrally in the other part. It is especially common for joinery frameworks. From gate pin the carpenter says the carpenters called each square mortise slot, and speaks of shear pins because it prevents swinging out on the corner without bracing. Typically, the mortise and tenon frame can be reinforced by iron flat angles, or improved if it has already been worked out - typical on rustic windows and doors, the false hook, as there are also common tang-and-angle constructions, called for example Winkelband or Styrian window band.

with groove ( chiselled work )

The shear pin connection is created by cutting a number of pins on one part and cutting a number of corresponding recesses in the other part, which interlock in a comb-like manner ( dovetailing ) . This fork, slot or shear pin connection is made by cutting an upwardly open mortise at the end of one part that mates with a tenon cut centrally in the other part. It is especially common for joinery frameworks.

Pegs

With this mortise and tenon joint, a specially shaped tenon is produced which is inserted through a corresponding tenon hole in the other part. The pin protrudes over the other part and is wedged at the end.

Dovetail joint

This connection is made with a conical peg, the angle of inclination of which is usually 1: 8 for hardwood and 1: 7 for coniferous wood, the peg hole also being designed in a corresponding dovetail shape. See also: dovetail connection

Hunting cones

The hunting spigot , also known as hunting spigot in Austria , is used for a headband , the diagonal bracing between the beam and the post (the spar and the handle), if it is necessary to insert this between the handle and the spar. One end of the pin is bevelled so that the headband can be rotated around the other pin during assembly. The headband is inserted into the tenon hole of the beam and rotated around this - generally upper - point by blows, in that the hunting pin is driven into the lower tenon hole ("chased into", hence the name of this version). The headband equipped with a hunting pin is also called a hunting band .

Sprout cones

As shoot pin is referred to the wood - or in replacement with metallic pins - existing mortise, the compound of the rung and ladder serves. The sprout cone was described in 1874 by the carpenter Hermann Webermeier in his manual textbook Die Deutsche Tischlerei .

Related forms

- Some forms of interlacing can be seen as a special form of mortise

- The use of numerous small tenons forms the galvanization

- The tenon can also appear as a subordinate element in other connections, such as offset or clawing

literature

- Theodor Krauth, Franz Sales Meyer (ed.): Building and art carpentry . 2nd Edition. Seemann, Leipzig 1895, IV. The wood connections, considered in isolation. , S. 76-96 .

- The carpenter's book 1895 . Th. Schäfer, Hannover 1981, ISBN 3-88746-004-9 (reprint).

Web links

- Declaration on the homepage of the Landesberufsschule Wals, Salzburg

Individual evidence

- ↑ Krauth, Meyer (Ed.): The Zapf . IV.5b., P. 90 f .

- ↑ Krauth, Meyer (Ed.): Fig. 69 h . IV.5b. The mortise, p. 90 f .

- ↑ Schachermeier: Catalog building fittings

- ↑ paragraph after hunting cones . In: Günther Wasmuth (Hrsg.): Wasmuths Lexikon der Baukunst . Berlin 1931

- ↑ Sentence after Jagdband . In: Günther Wasmuth (Hrsg.): Wasmuths Lexikon der Baukunst . Berlin 1931