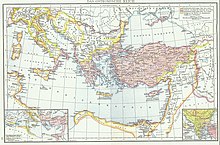

History of Anatolia

The history of Anatolia, together with the prehistory , which can be documented by fossils of the genus Homo and stone age tool finds, goes back more than a million years. For example, in the prehistoric deposits of the Gediz River, the oldest reliably dated Stone Age tool on Turkish soil was discovered, a worked fragment around 1.2 million years old. These early inhabitants - they are usually referred to as Homo erectus in the professional world - were later followed by the Neanderthals and finally by anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens). Its early hunter-gatherer cultures disappeared around 12,000 years ago.

The fertile crescent , in which around 11,000 BC The Neolithic revolution began, is to a small extent on Turkish territory; Boncuklu and Pınarbaşı are the oldest Anatolian sites that were found between 8500 and 8000 BC. Chr. Settlement and a long-term inhabited settlement can be proven. Monumental architecture and a large-scale exchange of obsidian emerged early on . From 8300 BC BC began the expansion of the way of life, which was characterized by agriculture, livestock and stockpiling, as well as villages, towards the west. The most famous excavation site is Çatalhöyük (7400-6200 BC), a protourbane settlement. During the late Copper Age (up to 3000 BC) there was a massive increase in settlement activity, so that thousands of villages were accepted. The post-Copper Age settlements in Southeast Anatolia, however, were considerably smaller, much more scattered, and mostly they were newly founded. The early Bronze Age on the Anatolian plateau, on the other hand, is considered to be a time of increased "urbanization", the first domains emerged. The use of metals is considered to be one of the most important causes of increasing centralization. Around 2000 BC A written tradition began with Assyrian sources for the first time, a rudimentary administration becomes recognizable, the cities reached considerable dimensions.

Possibly it came around 2000 BC. Through immigration to an ethnic fragmentation in the east. This phase of decline was followed by strong urban growth. In Central Anatolia, around 1600 BC. The great empire of the Indo-European Hittites , in the west the kingdom of Arzawa , which was probably inhabited by Indo-European Luwians . In the southwest the first Minoan , then Greek ( Mycenaean ) Miletus emerged . Other places on the Aegean coast, such as Iasos or Halicarnassus , were also from the late 15th century BC. BC probably settled by Mycenaean Greeks. At the beginning of the 12th century the Hittite empire collapsed, probably due to internal turmoil and the consequences of population movements and wars that affected large parts of the eastern Mediterranean. However, some of the smaller Hittite successor states continued to exist in the south and east of Anatolia until the 8th century.

The Phrygians spread from the 12th century to the east, towards Central Anatolia and possibly established an empire as early as the 11th century, which was administered from Gordion in the 9th and 8th centuries BC. BC included large parts of western and central Anatolia. Since 850 BC The empire Urartu existed in the east , at the end of the 8th century Cimmerians reached Anatolia, the 697 or 676 BC. The capital of the Phrygian empire destroyed around 644 that of the Lydians . Not until 600 BC The equestrian people were expelled from the country in the 4th century BC, but a few decades later the Persians conquered all of Asia Minor . Despite frequent clashes between Greeks and Persians, the Greek cities grew into important centers of trade and culture.

With the conquest of Anatolia by Alexander the Great , the country became a very frequent theater of war. After the collapse of the Alexander Empire, several successor states established themselves there, especially Pergamon in the west, Pontos around the Black Sea and Armenia in the east. From 133 BC. Pergamon and Pontus fell to Rome , but Armenia remained a buffer state between the Roman and Parthian empires for several centuries , which was replaced by the Persian Sassanids in AD 226 . Urbanization reached its peak in the Roman Empire. In late antiquity , Asia Minor still had over 600 cities. The early Christian groups, some of which opposed the secularization of the church, fought each other, but by the end of the 4th century non-Christians were already in the minority. By the 6th century, local landowners obtained almost unlimited power of disposal and police power by law, growing economic units demanded work and taxes from the peasants and, in a long process, turned them into unfree colonies who were tied to the clod and no longer owned free property.

The Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire triumphed over the Persians in 628 after a long war, but from 633 it lost large areas to Muslim Arabs , who also conquered the Persian Empire. At the same time, the loss of almost the entire area between the Danube and Greece to the Avars and Slavs made the remaining Anatolia the heartland of the rest of the empire. It was divided into military districts and all forces were subordinated to the defense against the Muslim armies, which repeatedly invaded Asia Minor. After around 850 the situation stabilized, from around 940 Byzantium went increasingly on the offensive, so that the extreme east of Anatolia, which owes its name to the Byzantine military district ( theme ) Anatolikon , was occupied.

Turkish Seljuks defeated an army led by the emperor in 1071. In Anatolia, around Konya in 1081, an independent Seljuk rule was established that extended to the Aegean Sea. Byzantium managed to recapture the coastal fringes, but after a heavy defeat in 1176, the rule of Constantinople began to crumble. In addition, the dispute with the Roman Church escalated from 1054 and 1204, an army of crusaders conquered the capital on the Venetian initiative. The Empire of Nikaia , founded by fugitive members of the imperial family, succeeded in stabilizing its western Anatolian rule, just as another branch succeeded in founding the Empire of Trebizond , which existed until 1460. With the recovery of Constantinople in 1261, Byzantium neglected Anatolia, which was gradually conquered by Turkish groups. Among them the Ottomans prevailed, who in 1453 succeeded in conquering the Byzantine capital, which they made Istanbul their capital . The Greek population continued to migrate to the coastal cities, Central Anatolia became an agricultural country and lost many of its cities. Lesser Armenia remained in the east until 1375 . Although the Seljuks were defeated by the Mongols in 1243 and the Ottomans by Timur's army in 1402 , this defeat could only delay the Ottomans' conquest of the Turkish Emirates.

They succeeded in conquering southeast and eastern Anatolia against Egyptian-Mamluk and Persian-Safavid resistance, but the constant warfare and excessive demands on the area resulted in uprisings. In addition, the importance of the cities continued to decline, especially since the Mediterranean trade increasingly lost importance compared to the Atlantic trade in the 17th century. The centrifugal forces increasingly dominated local politics, in the course of the 19th century the empire also lost most of the European territories and North Africa made itself independent, so that Anatolia once again became the heartland of the empire. After the First World War , the Ottoman Empire ended and the Turkish Republic was founded by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk . Although there were elections, the army staged three coups in 1960, 1971, and 1980, and a leadership made up of the military directed the country.

The largest minorities were Armenians , Greeks and Kurds , with the former facing genocide during the First World War and the Greeks being expelled from Anatolia after the war . Apart from the European part of Turkey, the state has consisted almost exclusively of Anatolia since the 1920s, where the government tried to negate ethnic conflicts, for example by making the Kurds a special form of the Turks. In 1996 parliament ended the state of emergency in the Kurdish provinces. The opening of the markets with low wages and a lot of catching up to do, together with the modernization of the organizational and infrastructure and the increase in education, led to rapid economic growth, from which the big cities in particular benefited, while soon barely a quarter of the population was living in rural areas .

Paleolithic (Paleolithic)

As much as Anatolia has gained in importance for the study of the Neolithic , the yields so far with a view to the Paleolithic have been so low . While great progress has been made in the neighboring countries of Georgia and Greece in the last few decades, Anatolia has suffered considerable neglect in this sector. Since the oldest hominine fossils to date were found north of Anatolia, in Dmanissi , Georgia , which are considered to be a possible link between the earliest representatives of the genus Homo from Africa and the later fossils of Homo erectus known from Asia , Anatolia would thus have a bridging function.

In neighboring Thrace there are mainly choppers , i.e. rubble tools, but almost no hand axes; In Anatolia hand axes can be found in all regions, but at only four sites their age can be determined on the basis of the stratigraphy (status 2009). Stone tools and bones from the Paleolithic and Mesolithic were discovered in the Karain Cave 31 km northwest of Antalya , including hand axes. The oldest finds were dated to an age of more than 400,000 years. Also datable hand axes were found at two sites near Şehremuz Sırtı north of Samsat in Southeast Anatolia ( A 5 and A 10 ), which could be assigned to the Acheuléen . The density of finds is greater on the upper Euphrates and on the Tigris as well as in the Hatay province .

In 1984 the first hand ax was found on the Euphrates near Şanlıurfa and thus the first evidence of the presence of people in the Paleolithic, even though the first hand ax was discovered in 1907 near Gaziantep . The first Central Anatolian excavation site to unearth finds from the Acheuléen was Kaletepe Deresi 3, discovered in 2000 near Kömürcü in Cappadocia ; they reach an age of about 800,000 years. In the area of the over 2100 m high Göllü Dağ , which is characterized by strong volcanic activity , obsidian stores were located, which attracted hunters and gatherers early on, who processed the glass-like material into weapons and tools. There were Chopper , Cleaver ( cleaver ) and hand axes . Tools that were made using the Levallois technique and are accordingly assigned to the Middle Paleolithic are also known. Only the lower jaw of an extinct horse species and a few teeth were found on animal remains. The older finds go back to Homo erectus . In 1940 a hand ax was found at Pendik in the Istanbul area , which was assigned to the Abbevillien , on the east side of the Bosporus a hand ax was found in three places near Göksu.

For the period between 40,000 and 26,000 BC There are relatively numerous finds between the Marmara region and Hatay, but after that there is a gap of six millennia. Accordingly, the Gravettia industry is completely absent .

During the largest Würm Age glaciation around 28,000 to 20,000 BC. In BC, the Mediterranean sea level was 100 to 130 m lower than it is today. The subsequent increase was caused by the melting of the ice masses, which dragged on for thousands of years. Since this process was not linear, the reconstruction of past coastlines is a complex task, whereby, in contrast to other regions, the land uplift and subsidence was rather small. The strong fluctuations in sea level destroyed prehistoric settlements, especially in the coastal plains, for example in Cilicia and the Antalya region . In the Aegean Sea , what is now the Greek islands were often part of the mainland, and when the sea level rose, the floods reached up to 70 km inland. The course in the Black Sea , whose connection to the Mediterranean did not exist continuously, is much more complicated .

The last time it happened was in the Younger Dryas between 10,730 and 9700/9600 BC. Chr. To a strong, global cooling.

Epipalaeolithic (approx. 20,000–10,000 BC)

For a long time only two sites in Anatolia could possibly be assigned to the Epipalaeolithic , the age that immediately preceded settling and agriculture and grazing. However, the Pınarbaşı site , an abri , has a camp of shepherds and hunters who settled in the 7th millennium BC. Stayed here. Among them were traces that could be dated to at least the 9th millennium. The hunters erected lightweight protective walls made of thatch that they found in the nearby lake. 90% of the obsidian they used came from Cappadocia . Microliths in particular were used, and stone tools were apparently brought along. Some burials contained numerous shells from the Mediterranean.

Characteristic of the Epipalaeolithic are the microlithic industries, which continued to exist in some regions of Anatolia afterwards. In addition, there was a recognizable cultural differentiation between the various regions for the first time. The most important survival strategy consisted of mobility and the use of resources, which are often far apart. In some favorable places there have already been repeated longer stays depending on the seasonal cycles. The hunter-gatherer societies, however, have long been neglected in favor of research into the earliest agriculture or the emergence of early urban settlement types. There is no recognizable demarcation from the Mesolithic on the basis of the finds .

As everywhere in Anatolia, wild plants were collected, such as pistachios , the fruits of the hackberry tree , raisins, pears, almonds and possibly already olives, traces of which can be found in caves such as Beldibi, Karain B (not to be confused with the Karain cave ) or Öküzini in the west and found north of Antalya. Grain was of little importance. Also at the most important site, the Öküzini Cave, whose oldest finds date from 23,000 to 15,000 BC. Kebaran culture dated to the 4th century BC and which lies at the foot of the 1715 m high Geyik sivirsi, no traces of grain were found. The cave mainly contains remains from the period between around 20,000 and 7500 BC. Chr.

While it was previously assumed that the sedentary way of life went back to the influence of the Mesopotamian PPNA , it is now assumed that it developed independently on the Central Anatolian plateau, which culminated in the Central Anatolian Neolithic (CAN).

In the area of the Black Sea, formerly an inland lake, many settlements are likely to have been destroyed when the Mediterranean collapsed over the Dardanelles and the Bosporus and the water level rose. The details are controversial, however. The oldest finds of marine animals in the Black Sea date to around 5500 BC. For more see Black Sea .

Neolithic (New Stone Age)

Thanks to intensive research on the question of the transformation of hunter-gatherer societies into societies that produced their own food, a clearer picture can be drawn from the 10th millennium onwards. Around 9000 BC The Neolithic Revolution began , which was characterized by agriculture, cattle breeding and village lifestyles, including urbanization. For a long time, apart from the areas bordering the Fertile Crescent, Anatolia played no role in European history either as a place of origin or as the beginning of food production. For some time, however, the core region of the earliest Neolithic, the Fertile Crescent, has been expanded to include the south-east of Central Anatolia. The borders to the west and north are still unclear. In any case, the Neolithic remained in this core region for a long time.

After the expansion towards western Anatolia, the Aegean region, Thrace and Bulgaria as well as northern Greece, a new core zone was created here. Western Anatolia became a contact zone. Between 1992 and 2012, 26 new sites were excavated in western Turkey, allowing the western expansion to date between 7400 and 7100 BC. To date, possibly even a little earlier. The sea route for some cultural transfers into the Aegean, such as Impresso ceramics, which was unknown in the hinterland, is made probable through excavations in Ege Gübre in Izmir, as well as through Neolithic finds in Cyprus and Crete. The same applies to Hoca Çeşme (around 6400 BC) on the west coast, which contained ceramics typical of the hinterland, but also circular buildings that cannot be found outside the coastal region. One can therefore assume a sea route close to the coast that connected the Levant with the Balkans. The so-called “Neolithic package”, a group of marks, i.e. goods and animals that were carried with them, developed. The animal races and plant species that were brought along - especially grains - came from the area of origin, as has been proven genetically. In addition, there were certain types of pottery that are characteristic.

A first phase of expansion towards the Balkans can be seen around 6500 to 6400 BC. Grasp. It is noticeable that practical items were carried along with cattle, but ritual, ceremonial and prestige objects were not. So it could have been a split without the elites and priests. One of the most important cultures that can be assigned to this process is the culture of Fikirtepe (6450–6100 BC), which has been documented in more than 25 sites. The locations in the hinterland, such as Ilıpınar or Menteşe Höyük , have rectangular houses, as were typical for Central Anatolia, while the coastal houses were round or oval. The latter applies to Fikirtepe , Pendik , İstanbul Yenikapı and Aktopraklık . While tombs lay outside the walls in the hinterland, they were found under the huts on the coast. Burning the dead on hills, like in Yenikapı, was completely unknown in the hinterland. Possibly it was a question of a westward movement in the hinterland, while on the coast there was a mixture with the life forms existing there - with immigration via sea. The next, relatively rapid wave of propagation reached the entire Balkans.

Excavations in Tepecik-Çiftlik and Köşk Höyük in eastern Central Anatolia indicate that the widespread types of ceramic processing - certain types of figurines, animal or human-shaped vessels, etc. - come from this region. The new settlers preferred river valleys and well-irrigated plains and avoided hills and plateaus. More than 100 sites can be assigned to this phase between Central Anatolia and the Aegean coast. In contrast, the eastern Marmara region remained unaffected. There the Fikirtepe culture was followed by the culture of Yarımburgaz 4 . The second wave of those moving westward did not cross the Bosphorus , but circled the cultures of Yarımburgaz 4 and 3 and thus the area around Istanbul, which belonged to this culture, around the Sea of Marmara further west.

Southeast Anatolia

The oldest secured Neolithic settlements in Southeast Anatolia were found on Batman, a tributary of the Upper Tigris . Of them turn Hallan Cemi the oldest, it was the last centuries of the 11th millennium BP dated. Demirköy , about 40 km downstream, is only a little younger and is ascribed to the first century of the 10th millennium BP . Another 20 km downstream is Körtik , already close to the confluence of the Batman and Tigris rivers. The three settlements were probably inhabited by one and the same group one after the other. The groups of finds go back to the Zarzien culture , for which the period between 18,000 and 8,000 BC. And which was a highly developed hunter-gatherer culture. The Neolithic settlements had close ties to sites around Mosul .

Only in Hallan Çemi and Demirköy were traces of elliptical structures made of stone, wickerwork and grout (the latter at least in Hallan Çemi). Two larger structures were found, with the skull of an aurochs hanging over the entrance of one of the two buildings . The buildings also had materials from far away areas, such as four small lumps of copper ore or obsidian from the area around Bingöl and Van , which was probably processed in the “aurochs skull house”. In Hallan Çemi there was also a larger square surrounded by fire-blown stones and animal bones. Some of the stone vessels could be related to this "fairground"; apparently food was being prepared in them.

In contrast to the later, Neolithic sites, in these proto-Neolithic settlements on Batman, the dead were buried outside, for example in caves. In Demirköy, on the other hand, the dead found their final resting place within the village, albeit without any additions. These only appear in Körtik, such as stone vessels and pearls. Two buried dogs were found in Demirköy, as well as burnt bricks were found here for the first time.

At least for Hallan Çemi, first attempts at animal husbandry - of pigs - can be shown, which were replaced by goats in Demirköy . Apparently, wild grain was not harvested; it was rather nuts, legumes or the seeds of common beach cornices . So it was still experimented with different resources; Attempts that still depend heavily on local adjustments and run counter to the idea that it was an ongoing process of domestication.

Çayönü is about 125 kilometers above the Batman settlements . There the development from the circular buildings of an early farming settlement from the 10th millennium to a large settlement with rectangular, then differentiated buildings in the 9th to the beginning of the 7th millennium can be documented. Around 9500 to 9200 BP , the culture there changed in a different direction.

With Göbekli Tepe , the finds condense into a more precise picture. There originated around 10,500 BC. A mountain sanctuary, which is probably the oldest known temple complex. The curvilinear building was built on previously undeveloped land. Up to 500 people were required during construction to break the 10 to 20 tons, in extreme cases even 50 tons, in the quarries in the area and to transport them 100 to 500 m. These monumental, T-shaped pillars have reliefs in the shape of animals and humans. The dead were buried in this ossuary , but they were not given stone vessels as in Körtik. So far no residential buildings have been found, but "special buildings" that probably served ritual gatherings. At the beginning of the 8th millennium, the settlement lost its importance, but it was not simply forgotten, but was covered with 300–500 m³ of earth for unknown reasons.

Several settlements were found in the Euphrates region, including Cafer Höyük , which existed between the last centuries of the 10th millennium BP and around 8000 BP . The equally pre-ceramic, at the same time Neolithic, Nevalı Çori , whose oldest find dates back to the 10th millennium, is of similar importance , as are finds from Çayönü in the Tauros, which also include large sculptures.

Not only figurines were made from clay, as in Demirköy, but also vessels. Five excavation sites of this ceramic Neolithic can be found in southeastern Anatolia: Çayönü , Sumaki (the closest tributary of the Tigris downstream, the Garzan) and Salat Cami Yanı in the Tigris region and Mezraa-Teleilat and Akarçay Tepe in the Euphrates region. In Çayönü, the wattle and daub buildings were replaced by stone houses in the more recent phase. Settlement continuity can also be demonstrated for Mezraa-Teleilat. Overall, the ceramic phase of the Neolithic is characterized by smaller settlements than the preceding, pre-ceramic phase, in which monumental buildings were built in some settlements. It was not until the subsequent Halaf period that large settlements reappeared.

Central Anatolian Plateau

The earliest Neolithic Anatolia ( Pre-Ceramic Neolithic A ) knows no (or very little) ceramics, but already permanent settlements with round houses made of stone ( Nevali Cori , Göbekli Tepe ). In the following Pre-Ceramic Neolithic B , rectangular houses came into use. Clay was made into statuettes and sometimes also fired, but no vessels were made from this material yet.

Some sites show the gradual transition to the typical Neolithic way of life. Pınarbaşı is the oldest Anatolian site, dating from 8500 to 8000 BC. Was permanently inhabited for a long time. Half of the houses under the surface of the earth had wattle and daub above ground. The floors were plastered, and some were probably decorated with red ocher . The inhabitants made their living from hunting, especially for aurochs and solipeds , but also fishing and collecting wild plants such as pistachios and almonds . Obsidian and flint were fetched from afar and worked on site.

20 km from Pınarbaşı and 9 km from Çatalhöyük is the Boncuklu site , which is also culturally between the two sites. There were colored paintings that are similar to those in Çatalhöyük, as well as obsidian from Cappadocia - especially from Nenezi and Kayırlı , two of the main deposits - and Mediterranean shells (as in Pınarbaşı).

Also in the 9th millennium BC BC belongs to Aşıklı Höyük in Cappadocia . Between 8400 and 7400 BC BC to 6500 BC A year-round inhabited settlement existed here on Melendiz . After they finally settled down, buildings appeared that apparently took on special functions. The group of houses in the north of the hill, which had two to three rooms and looked very similar to one another, were made of adobe bricks , clay slabs and mortar. They had connecting doors, but no external doors, so that it is assumed that they were entered with wooden ladders via the flat roofs. New buildings were built on top of the old ones, the remains of which were recycled. This resulted in a total of ten construction phases. The houses south of the four-meter-wide street that separated the two parts of the settlement were made of different materials and had paintings. In addition, cultivated plants such as einkorn , emmer and barley , wheat and durum wheat appeared for the first time , although the hunting and collecting of wild plants continued. The burial places were inside the houses under the floors. On the opposite side of the Melendiz was Musular (7500-6500 BC), which was probably built by the residents of Aşık Höyüks. Blades and hunting weapons such as arrowheads were apparently made there, but most of all animals were slaughtered and cut up, and the site may have served ritual purposes. Because of this close connection to Aşık Höyük, one also speaks of the Aşık-Musular-Complex.

One of the most important sources of obsidian was the 1600 m high Kaletepe at the foot of the Göllü Dağ . The settlement can be traced back to the time between 8200 and 7800 BC. To date. Large quantities of preliminary products for the coveted obsidian blades were found there, so that one can assume that there will be widespread trade, which is also supported by the highly standardized cores and blocks. However, neither the technology nor the products existed on the surrounding plateau, but in the area of the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic B of the Euphrates region and on Cyprus . Hence, speculations arose that less Anatolian and more Levantine craftsmen lived here.

Examples of the oldest Neolithic ceramics are known from Çatalhöyük (7400-6200 BC) and Mersin . Çatalhöyük is considered to be the oldest city in the world. It covered an unusually large area of over 13 hectares, so that several thousand inhabitants must be expected. Domesticated sheep and goats now provided the majority of animal food, and there was still hunting and fishing as well as collecting activities in a rich flora. There were no buildings with special functions and only a few streets or passageways. Here, too, access to the house is likely to have taken place via flat roofs, the houses mostly had a main room and a few ancillary rooms, probably for supplies. A distinction can be made between benches, ovens and stoves, garbage pits and pillars. There were paintings, reliefs, decorated cattle horns, figurines and "history houses" with numerous burials. Around 6200 to 6000 BC The city was moved from the east to the west hill.

Expansion and “Second Neolithic Revolution”, two main hiking trails

Less attention was paid to the advanced Neolithic phase, sometimes referred to as the “ second Neolithic revolution ”, in which, in addition to the animal as a mere supplier of meat, other possibilities of animal use appeared, be it the production of wool, eggs and milk or the use as carrying and draft animals as well as a supplier of construction and heating material (manure). This phase also saw the expansion of the area in which people lived in this way, beyond south and south-east Anatolia to all of Anatolia and towards Greece and the Balkans. In the first half of the 7th millennium BC, Knossos on Crete was the only Neolithic settlement on the whole island. Around 6500 settlements also appear on other Aegean islands.

Genetic studies on the oldest Neolithic human remains in Greece have shown that the mainland Greek settlers were more closely related to those in the Balkans, while the inhabitants of the islands were closer to the inhabitants of central and especially Mediterranean Anatolia. In addition to studies on bread or common wheat , this indicates that there was a split in the settlers towards northern Greece and the Balkans or towards Crete and southern Italy, which already occurred in the early Neolithic. Therefore, common wheat is almost characteristic of the southern Anatolian, Cretan and Italian groups. In all likelihood they were moving across the sea. In terms of spread, if one follows further genetic studies, reproductive advantages over the respective neighboring hunter-gatherer societies seem to have played a decisive role.

Numerous early Neolithic settlements are located on the Beyşehir and Suğla lakes in the south of central Anatolia, for example Erbaba . This settlement was dated from 6700 to 6400 BC. Dated. The hill has an area of about 5.5 hectares. No streets separated the houses from one another.

Chalcolithic (Copper Age, approx. 6100-3000 BC)

The Chalcolithic period of Anatolia is characterized by multicolored painted ceramics. The early part of the Copper Age is around 6100 to 5500 BC. The oldest copper objects in the form of pearls come from Cayönü Tepesi and date back to between 8200 and 7500 BC. BC back. Above all, the settlement of Hacılar Höyük is known , the oldest layers of which belonged to the pre-ceramic Neolithic and date back to the eighth millennium BC. To date. In Layer VI (5600 BC) there were nine buildings made of adobe bricks, which were grouped around a large square. The inhabitants lived on emmer, einkorn, wheat, barley and peas as well as on beef, pork, sheep and goat. Dogs were also kept. Numerous clay figurines represent women. The settlement of layer I (around 5000 BC) was probably inhabited by newcomers who walled the place. The ceramics are finely crafted and mostly painted red on white. In the meantime, studies refute the image of a uniform transition to multi-colored painting, because it has also been proven in older, Neolithic sites such as Höyücek .

A distinction is made between the early Copper Age (5500-4000 BC) and the Late Copper Age (4000-3000 BC). First of all, the term Copper Age was supposed to mean nothing else than that in the three-stage model (Stone, Bronze, Iron Ages) there was a time between the Stone Age and the Bronze Age when copper was used. But the terms accumulated over time, which concerned the temporal delimitation - copper was already found in the ceramic Neolithic - but also the dominance of the material itself. Now the said colored painted pottery was considered characteristic, but there are only a few regions from the Middle and Late Copper Age in which this type of processing was in use. While the beginning of the Copper Age with its transition to the aforementioned ceramics, which was significant for archaeologists, was hardly perceived as a turning point for contemporaries, on the contrary, this may be all the more true for the time around 5500 BC. Were valid for the beginning of the Middle Copper Age, because many of the old settlements were abandoned. In addition, the Marmara region only adopted a permanent sedentary way of life and cultivation of the soil in the late Copper Age; the same applies to parts of the Aegean region. There developed in the 1st half of the 4th millennium BC A first settlement ( Milet I).

Çatalhöyük was also affected by major changes. Although Çatalhöyük West, which is on the other side of the Çarşamba River, is considerably smaller than Çatalhöyük East, which is connected to the older Çatalhöyük East, it is still the largest Copper Age settlement on the southern Anatolian plateau with 8 hectares. The youngest phase of the older settlement shows great similarities with the oldest phase of the younger settlement. This could indicate a successive “move”.

In the period up to 3000 BC There was a massive increase in settlement activity, so that thousands of villages were assumed that were in close contact with one another. In the southeast, a distinction is made between the Halaf and Obed cultures, whose names are derived from Mesopotamian sites. Before this time, there were more contacts in the direction of Nemrut , because obsidian discovered in Tell Hamoukar in northeast Syria came from this 3500 m high mountain . Tombs and houses show traces of siege, but above all more than a thousand clay balls that were supposed to be used as projectiles. The city was possibly founded by Uruk around 3500 BC. Chr. Destroyed. The Sumerians later founded a trading colony there, with which the region was oriented southward.

Bronze age

The Bronze Age is recorded in western and central Anatolia from around 3000 BC. BC. However, the delimitation of the first phase (Bronze Age I, up to 2700/2600 BC) to the Copper Age is unclear, the second phase (2700/2600 to 2300 BC) is still poorly understood and the third (2300 to 2000 BC). Chr.) Goes over to the time of the first great empire in the region.

In southeastern Anatolia, the Bronze Age continued around 3400 to 3300 BC. A. The further subdivisions are controversial in this area, which is strongly influenced by Mesopotamia. The post-Copper Age settlements were considerably smaller, much more scattered, and mostly they were newly founded.

Early Bronze Age (approx. 3400/3000–2000 BC)

The early Bronze Age on the Anatolian plateau is considered to be the time of increased "urbanization", comparatively large settlements with complex structures and a wide-ranging trade network that began around 2500 BC. Chr. Can be better understood. Settlements with an area of around 8 or 9 hectares were dominated by a ruling class whose power extended into the surrounding area. This development began before the Bronze Age, for example in Troy I, Beycesultan , Karataş and Küllüoba . In the early Bronze Age, settlements such as Liman Tepe and Çadır Höyük in the northern central plateau or Tarsus and Mersin in Cilicia had hierarchical structures. The exchange intensified within their regions, which may already be considered rulers, and ceramics were increasingly created on the potter's wheel .

In western Anatolia, cemeteries were created outside the city walls in the second phase of the Early Bronze Age. For example, 500 graves were found 25 km west of Eskişehir in Demircihöyük Sariket, of which a considerable number probably represented a kind of family tomb. The village itself was only 70 meters in diameter; the megaron- type houses were arranged in a circle around a central square. In the third phase, the grave equipment and the grave goods were more expensive, which is interpreted as a sign of increasing social differentiation.

One of the most important reasons for the increasing centralization is the metal trade, which mainly took place between 2700/2600 and 2300 BC. And to which the trade in clay pots joined. Many archaeologists assume a dense trade network for this phase that stretched from the Black Sea to southeastern Anatolia. Production was boosted by tin finds in the Taurus Mountains , the ores of which found their way to western Anatolia; The aforementioned clay pots went in the opposite direction. Cities like Kültepe , whose long-distance trade in pottery reached as far as the central Euphrates, played a major role in this extensive exchange .

At the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, Assyrian sources report of Luwians and Hittites in Central Anatolia who used Indo-European languages , which also included Palaic , as well as Hurrians (in northern Syria ). When and from where these groups came to Anatolia is unclear. The way in which the different populations live together is even less clear.

In Western Anatolia, the megaron appeared as an architectural mark at the beginning of the Bronze Age . Troy I began around 3000 and ended between 2600 and 2500 BC. The settlement was protected by 2.5 m thick walls, three city gates allowed entry. One of the Megaron buildings had a hall measuring 7 × 18.5 m. One of the largest settlements in Western Anatolia was Beycesultan , which dates back at least to the Copper Age. Troy II, which existed between 2700 and 2500 BC. BC, was considerably larger than the previous settlement. At least five Megaron buildings can be proven. The function of these buildings, which are very different from residential buildings, is unclear. From Troy II comes a depot that is considered the largest of this phase and was probably buried in the wake of a city fire.

Contrary to earlier assumptions, there was considerable settlement continuity between the middle and later Early Bronze Age, as has been shown by finds in Troja III, Küllüoba , Liman Tepe or Bakla Tepe . Stone houses now predominated in Troy, which was perhaps a reaction to the conflagration.

In the northern central plateau, the number of Early Bronze Age sites is considerably lower, although traces of settlement were found in Paphlagonia . The “royal tombs” of Alaca Höyük and Alışar Höyük , which were visited by the Assyrians , and the nearby Çadır Höyük are among the few sites.

In phase II of the early Bronze Age the find situation is even leaner than in phase I, although the situation on the northern plateau is still more favorable than on the southern plateau, where mainly Tarsus was productive. So far, no building remains have been discovered in Çadır Höyük, although broken fragments have been found. In Alışar, as in the earliest phase, stone-lined walls remained the rule, which also continued to consist of adobe bricks. In phase III, this region was also integrated into the whole of Anatolia-wide trade and urbanization. This is shown above all by finds from Alaca Höyük , Mahmatlar and Horoztepe . In many cities, the walls were significantly reinforced.

The 19 graves of Alaca Höyük , 14 of which the excavator referred to as “royal”, are stone boxes in which the remains of one individual, but occasionally two or three, were found. The graves were covered with wood on which cattle bones were found, which are interpreted as sacrifices. Among the grave goods were human and animal-shaped figurines, weapons, jewelry and metal and clay objects as well as the bronze standards of Alaca Höyük . The metal objects consisted of gold, silver and electron as well as copper.

Tarsus , long focused on Mesopotamia, turned shortly after 3000 BC. BC stronger to Anatolia. The causes were sought in changes in Uruk , but also in the tin finds in the Taurus Mountains. In Phase II of the Early Bronze Age, two-story houses were built, but not of the megaron type. After a devastating fire, an almost three meter thick city wall was built.

By contrast, found themselves in Bademağacı , about 50 km from the center of Antalya removed traces a circular hilltop village, which consisted of 70 to 90 buildings. Clay seal fragments suggest rudimentary administration. Kaneš , located 21 km northeast of Kayseri , which was mainly in the 2nd millennium BC. As early as the end of the Early Bronze Age, it was an important trading center. Its largest monumental building from this period measured 20 × 22 m.

In the northern Euphrates valley , Arslantepe , Kurban Höyük and Hassek Höyük , which had already existed in the Copper Age, continued to exist. Lidar , Hassek 5 and Tirtis Höyük were surrounded by thick city walls. There were only very small settlements south of these cities.

Rituals were performed on high platforms, such as in Surtepe and Tilbes Höyük . At Gre Virike there was a 1750 m² platform with monumental graves, similar to the one on the central Euphrates in Syria. In many settlements there were cemeteries outside the walls, as in the west there were also stone boxes ( Zeytinli Bahçe Höyük ) with rich grave goods (Birecik).

The middle phase of the Early Bronze Age is generally around 2700 to 2400 BC. BC. Titriş Höyük covered an area of 35 ha. Tilbeşar III B reached similar dimensions with 30 ha, which had a lower town where olive oil and wine were produced.

The later phase is mostly around 2400 to 2100 BC. BC, but appears around 2600 to 2200 BC. BC already a recognizable hierarchy between urban centers, smaller towns and villages. The above-mentioned centers on the upper Euphrates, which now housed lower towns, have a pronounced social stratification. Titriş Höyük grew to 43 hectares and apparently farms within a radius of 4 to 5 km were part of the city's sphere of influence. A ceramic workshop was found in Lidar; there was a separate artisan quarter. Tilbeşar III C covered an area of 56 hectares and olive oil and wine were also produced here. In Titriş Höyük houses with a floor area of up to 200 m² with 10 to 15 rooms were built. Extended families lived in these large households, and some had storehouses for grain.

After Naram-sin around 2200 BC. Chr. Ebla had destroyed, the form of settlement changed. Tilbeşar III D was abandoned and the dominant urban centers began to decline in the southern part of the central Euphrates region, combined with increasing migration to the smaller towns. Before 2000 BC The monumental tombs disappeared. In addition, the quality of metalworking decreased. Also on the Tigris can be seen around 2200 BC. Show a decline of the larger centers. Important trade routes may have been relocated south. Naram-Sin had a palace built on Tell Brak , now in the far north-east of Syria, from which the Chabur trade route should be controlled. There was a stele of the Akkadian ruler.

In Eastern Anatolia the situation is even more complicated. There the early Bronze Age culture is also referred to as the early Transcaucasian culture, as it is assumed that many cultural features originated in the area of the Caucasus . The ceramics there did not appear until the end of the 4th millennium, while previously only the red and black goods predominated. It is found from around 3500 BC. In Arslantepe VII, Sos Höyük VA and Çadır Höyük and possibly comes from Central Anatolia. Metal finds and transportable stoves, on the other hand, have their origin in the region north of the Caucasus.

Today it is assumed that the recognizable migratory movement was part of a movement from the southern Caucasus to the Levant. Another characteristic of this culture is the fact that it could coexist with other cultures, which finds from the area around Elazığ and Malatya show. In the upper Euphrates valley, Transcaucasian and Syro-Mesopotamian cultures alternated between 3300 and 2800 BC. Several times from. On the other hand, Pulur-Sakyol and Norşuntepe , one of which was Transcaucasian and the other Syro-Mesopotamian, coexisted.

The royal tomb of Arslantepe , discovered in 1996, is symptomatic of the simultaneity of these cultures with regard to ceramics ; on the other hand, the metal finds point to a Transcaucasian origin. While there was a reorientation from Mesopotamia to Anatolia at the end of the 4th millennium in the south, i.e. on the upper Euphrates, which at that time was still densely forested, the northeast developed more evenly on the basis of autochthonous cultures. It is noticeable that sheep and goats abruptly displaced other herd animals, such as in Arslantepe. In contrast, the relationship between the domestic animal populations in the Erzurum region did not change. Another factor contributing to the confusing diversity in Eastern Anatolia is that different house and settlement types existed at the same time. Also in the Erzurum area at the end of the Early Bronze Age there are no cultural breaks, but rather signs of great continuity. Quite different around Lake Van, where a sharp cultural break can be observed; apparently there was an extensive reputation here.

Middle Bronze Age (2000–1600 BC)

The Middle Bronze Age of Anatolia is usually divided into two phases, which are provided with Latin numbers. The Middle Bronze Age I extends from about 2000 to 1800 BC. Chr., II joins and extends to 1600 BC. Phase I is best understood by the Assyrian traders present in Anatolia, who left numerous seal impressions and business letters, which for the first time allow insights into the political, social and economic situation of some parts of Anatolia. Phase II, however, is characterized by the early, first Anatolian empire, that of the Hittites .

Central Anatolia, Assyrians

The Middle Bronze Age offers extensive written sources for the first time. This is due to the fact that traders from Assur (Aššur) had built up a trade network and went to Anatolia for this purpose. The Karum period in southeastern Anatolia received its name from these bases, which were named Karum after the Akkadian word for port or quay . There one understood by it the dealer colony or its main building. The period ranged from around 1950 to 1800 BC. The main trading center for fabrics, tin and silver was Kaneš , today's Kültepe, 20 km northeast of Kayseri , which extended over an area of 50 hectares. More than 24,000 seal impressions have been found in Anatolia from this period.

Southwest of the Tuz Gölü , the number of Middle Bronze Age sites is extremely small, although Assyrian seal impressions with cuneiform were also found in Karaböyük Konya, which also extended over 50 hectares. Larger urban centers were located around the Tuz Gölü. This includes Acemhöyük , one of the largest Middle Bronze Age sites, which is located on a hill southeast of the lake. The city with an area of 56 hectares was destroyed by a conflagration. Two palaces date from the Karum period, but no Assyrian trading district can be proven. On the other hand, there were seal impressions of King Šamši-Adad I.

Alışar Höyük in the southeast of the Yozgat province measured 28 hectares and was inhabited from the 4th to the 1st millennium. Traces of fire indicate destruction at the end of the Bronze Age. In addition to this later Hittite provincial town, Ḫattuša was especially important. Overall, Mesopotamian-Assyrian influence made itself felt in artistic production, in commercial goods and in the standardization of measurements and weights, but also in funeral rituals. Thus, according to Assyrian custom, the dead were buried under the floor of the house. Stamp seals of the Anatolian tradition remained in use, but cylinder seals now predominated.

For the first time we learn something about political history. A list of names of Assyrian kings was found in Kültepe, which ranges from Erišum I to Naram-Sin , i.e. perhaps from 1974 to 1819 BC. Most of the texts, however, offer very few names of Anatolian rulers, such as Waršama, the king of Kaniš.

The regions into which the Assyrians had insight were politically highly fragmented. Many independent, fortified cities formed small states, while some larger cities also dominated their surrounding areas. In addition, there were vassal states such as Mamma and Kaniš. Karum were in 20 cities, the smaller Wahartum in 15 other cities. Some of the bases further to the west were founded in the 18th century BC. Abandoned. Kaniš, the headquarters of Assyrian trade, expanded its sphere of influence from 10 to perhaps 20 villages in the area. The city-states were ruled by "princes" who belonged to dynasties. Because fights between cities could hinder trade, they were mentioned many times in letters from traders, as well as existing coalitions of several cities. A merchant colony had to leave the city if the opposing city required it or if there were unrest and uprisings.

In the later phase of the ancient Assyrian trade the kings of Kaniš can be named: Ḫurmeli, Ḫarpatiwa, Inar and his son and successor Waršama, Pitḫana, who conquered Kaniš and took Waršama prisoner, and his son Anitta, who is already referred to as the "Great King" was, as well as Zuzu, who also carried this title after he had also conquered the city. Behind these struggles hid not only a political and military power, but also a differentiated state apparatus. The sources differentiate between about 50 titles at court. The highest titles were held by the prince and royal couple who ran the state. A rabbi sikktim was responsible for the military and trade, and responsibilities had evolved from ceremonial offices. The lord of the workers led title holders who directed individual trades, such as the blacksmiths or the walkers.

The palace itself was landowner, as were the holders of the aforementioned titles. Apparently the townspeople were no more landowners than the foreign traders, so they were dependent on the market. Some properties were permanently obliged to perform certain services, others had characteristics of private property, and still others were domains. Common land ownership was common. Each landowner had to give part of his harvest to the palace. Some of the small farmers had to borrow grain to get through the year, while some dignitaries owned entire villages. Most of the land was planted with barley and wheat, although a total of twelve types of grain were known. Storehouses apparently existed, the palace knew a "lord of the storerooms". The grain was mainly consumed as bread or porridge, barley was processed into beer. Sesame oil was used for food preparation, but also for lighting. Forage, vegetables and fruit were planted in the gardens; Wine and spices were produced. The irrigated fields were subject to tax, and a corresponding “lord of the irrigated fields” was responsible. Sheep and goats were kept on the domains, whose milk, wool and meat were sold by the palace.

The Assyrian caravans - protected against taxes from the kings - found safe and adequately equipped caravanserais and rest stops. They brought Mesopotamian goods, which they exchanged mainly for gold and silver, which they were allowed to purchase at four locations. One shekel of gold (8.3 g) was equivalent to 6 to 8 shekels of silver. Copper was used for smaller purchases. It was mainly extracted from the Black Sea, in the area of the Kizil Irmak or near Ergani, in order to be transported southwards as bars or in another form. The caravans also brought tin from northwestern Iran and Uzbekistan to Anatolia, so that there was considerable dependence here. The metal was only processed into bronze in Anatolia. Iron, on the other hand, was very rare and was brought from Assyria or came from small mines in Anatolia.

The residents of Kaniš were allowed to buy grain, slaves and everyday necessities at the local markets, but they were only allowed to buy fabrics and pewter from the palace. While in the earlier phase of the Assyrian activity in Kaniš the Anatolians were often indebted to them, this situation seems to have been reversed. Now Assyrians were often indebted to other residents of the city and some became debt slaves. Most of the residents were farmers or shepherds, although the latter were free, but belonged to the poor. Some of the peasants did a kind of forced labor. The slaves were mostly debt slaves who had sold themselves or who had been sold by their parents. By paying twice the purchase price, often more, they could be freed again.

Bilingualism seems to have been the norm among the Assyrians, only the palace knew interpreters. Apparently the Assyrians introduced the script to Anatolia. In at least one case, an Anatolian king adopted the script and language of the immigrants in his documents. The Assyrians, for their part, used a simplified written form; conversely, the Assyrians adapted Hittite terms.

Men and women owned their goods together. Both had the right to get a divorce, for which a formal contract was drawn up in the palace. The children together could stay with their mother or father. If an Anatolian got into debt, he could mortgage his wife and children. The Assyrians of the first generation mostly returned to their homeland, but those who followed often married in Anatolia - on the condition that they did not live in the same house - a second wife besides the one in Assyria. Some divorce contracts show that the men sometimes returned to Assyria to their first wife, with the Anatolian woman keeping the house and the man remaining in charge of child support.

Southeast and Eastern Anatolia

Around 2000 BC On the one hand, the climate was unfavorable for agrarian societies; on the other hand, immigration led to ethnic fragmentation. During the Middle Bronze Age, the south-east and east of Anatolia were much more closely integrated into the more extensive trade network, and the urban centers also grew larger again. The Euphrates was used by traders on their way to Anatolia, so that old cities flourished again or new ones emerged along the caravan routes. Large centers were, for example, Karkemiš or Samsat . In addition, there were numerous fortress-like cities that may have been outposts of the centers. The middle-sized centers now also had their own, demarcated craft towns. Trade intensified considerably, as the archives of King Zimri-Lim of Mari or of the Assyrian King Šamši-Adad I in Šubat-Enlil (Tell Leilan) also show.

In particular, the excavations by Tilmen Höyük on İslahiye shed light on the situation in the 20 or so city-states that together made up the Kingdom of Jamchad . Like many other cities, the city was divided into a royal citadel with a palace and temples and a city, each with its own craft quarters. Tell Açana , the ancient Alalakh not far from the Orontes , had an area of 20 hectares. This city was also one of Yamchad's vassals. With 56 hectares, Tilbeşar was considerably larger and its palaces, city walls and temples increased the monumentality of the city-state architecture that characterized the entire region as far as Mesopotamia. At the same time, the influence of Cyprus, which increasingly replaced Anatolia as a supplier of copper, and Egypt increased. Trade across the Mediterranean also increased significantly, which was noticeable in the first larger ports. This influence was less further to the east, and contacts with eastern Anatolia were correspondingly more intensive.

In eastern Turkey, the settlements shrank, their number decreased drastically, the rectangular houses were much smaller. In addition to cemeteries with box graves, burial mounds or kurgans emerged , as they were typical for the entire region in the southern Caucasus.

Numerous small to medium-sized settlements emerged on the upper Tigris, sometimes specializing in certain crafts such as cloth production or clay processing. Hirbemerdon Tepe exemplifies how the cities were divided into a ceremonial and a work sphere . These two were separated from each other by a so-called plaza and a comparatively wide street. In addition, the production of wine could be proven here, which played an important role as a commodity towards Mesopotamia, but also for the ceremonial position of the palace. Nevertheless, the cities on the upper Tigris were rather small, most of them barely reached 5 hectares, and the social and administrative complexity is far behind the cities in the Cypriot-Egyptian sphere of influence. It seems that the vast majority of the population lived in small villages and delivered the surpluses to medium-sized centers such as Hirbemerdon. These centers with their specialized "industry" and the villages that provided goods and labor would therefore have been linked by rites.

Late Bronze Age (approx. 1600–1200 BC)

Western Anatolia

The history of Western Anatolia is known in fragments from Hittite texts. There, the land of Arzawa or Arzwawiya appears for the first time at the time of the Hittite king Ḫattušili I , who probably led a campaign against the country in connection with border disputes. Arzawa probably extended from the Aegean Sea to the west of the Konya plain. The Hittite king Tudḫaliya I managed to conquer Arzawa for a time. This by no means ended the wars between the two powers, as an invasion of the territory of Hittite vassals at the time of Tudḫaliyas II shows, but above all the diplomatic contacts that the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenophis III. with King Tarḫundaradu of Arzawa (the Arzawa letters from the Amarna archive found in 1887 ). Arzawa conquered parts of the Hittite Empire, but Šuppiluliuma I , the son of the Hittite king, prevailed against this coalition without being able to defeat Arzawa. Mursili II finally succeeded in conquering Arzawa. He had 65,000 or 66,000 residents deported, as he himself claimed. This was the end of the Arzawareich, whose capital was Apaša, probably identical to Ephesus , and which was founded in the 14th century BC. At times the most powerful empire in Asia Minor.

The inhabitants of Arzawa were the Indo-European Luwians. I.a. the Carians and Lycians , who are often mentioned in later Greek sources, spoke a language related to Luwian . It is unclear what the relationship between the Luwians and the still existing autochthonous , pre- Anatolian or pre-Indo-European population was.

From the end of the 14th century, after Mursili II had conquered the Arzaware empire , Arzawa was divided into several smaller empires, each of which was ruled by vassals of the Hittites. The realm of Mira succeeded Arzawa Minor , the heartland of the former Arzawareich. At the upper reaches of the meander was Kuwaliya , the capital of which probably corresponded to the current location of Beycesultan and which the Hittites tied into their sphere of power. North of Mira was Šeḫa (the river country), to which the island of Lazpa (Lesbos) also belonged. Šeḫa submitted to an invading army of Muršilis II. Finally, the Hittites bound Wiluša through a vassal contract (see also Alaksandu ), which, according to not undisputed theories, is to be connected with Ilios and therefore was part of the Troas . A king named Walmu was born around the third quarter of the 13th century BC. Overthrown by insurgents or attackers, but reinstated by Tudḫaliya IV , as can be seen in the so-called Milawata letter ( CTH 182).

Aḫḫijawa can very probably be identified with a Mycenaean empire , an assumption that initially led to the resemblance to Achaeans , one of the three names with which the Greeks were referred to by Homer . But also the geographical information about Aḫḫijawa lead many researchers to conclude that it was west of the Hittite Empire, and at least a larger part of Aḫḫijawa was beyond the west coast of Asia Minor, since its core area could apparently only be reached by sea. Whether a Mycenaean empire under the leadership of Mycenae or - as some new finds indicate - Thebes , which ruled the Greek mainland and the Aegean Sea , or possibly a smaller Mycenaean state, which was located in the southeastern Aegean region, is controversial. Aḫḫijawa had at least temporarily bases or colonies on the west coast of Asia Minor. Of these, Miletus at the mouth of the Meander and the Iasos site further south are Mycenaean settlements. More extensive finds have been made, inter alia. also made in Müsgebi (near Halicarnassus ) and Ephesus , so that it is assumed that Mycenaean Greeks also lived here at times.

In Miletus there were traces of Minoan settlement from the middle (Milet III, around 2000 to 1650 BC) and the late Bronze Age (Milet IV). Mycenaean Greeks may have conquered the settlement in the first half of the 15th century. What is certain is that from around 1400 (Milet V) the city now clearly has Mycenaean characteristics. Muršili II destroyed the "Millawanda" in the west towards the end of the 14th century, which had participated in an anti-Hittite coalition of some western Anatolian principalities. The majority of researchers equate Millawanda with Miletus and associate the destruction layer of Miletus V with the report on the destruction of Millawanda. The following Miletus VI shows clearly more Hittite elements. Tudḫaliya IV. (Approx. 1240–1215 BC) possibly succeeded in completely suppressing the influence of Aḫḫijawa on the coastal cities, which seems to have grown again in the course of the 13th century. The city wall of Milets, which was built in the second half of the 13th century BC. BC, shows strong parallels to Hittite city walls, e.g. B. the one in Ḫattuša.

In some western Anatolian areas, the Hittite rule was less noticeable. Perhaps in the later north of Lydia was Maša, where apparently a council of elders ruled instead of a king. It was only conquered under the last Hittite great king Šuppiluliuma II . Karkiša was also ruled by a council of elders , which probably gave the Kariern a ruling framework. Like Maša, Karkiša sometimes fights with and sometimes against the Hittites. At Lukka it was more of a city group with common ethnic origin between Western Pamphylia , Lycaonia , Pisidia and Lycia . Their language, Lycian , has been handed down in around 200 inscriptions and is very close to Luwian . In addition, these groups show the greatest cultural continuity between Bronze Age and Iron Age groups in Anatolia.

Central Anatolia: Hittites

The Hittites established the first great empire of Anatolia. They dominated the core of the area between the Pontus and Taurus Mountains, but led conquests and raids as far as the Aegean Sea and Babylon . They called the Konya plain "the lower land", while "the upper land" was the area around the Kızılırmak river . Although descriptions of the ritual processions of the kings and, above all, of the war campaigns exist, most of the names of cities, rivers and landscapes mentioned there cannot be identified with certainty.

The capital of the empire was Ḫattuša , about 150 km east of Ankara. Around 1900 BC The Hittites set in motion a series of migrations, but they were not yet subject to any central power. Their language, which they called Nesili , belonged to the Indo-European language family. Nesili was the language of Neša ( Kültepe ), which was one of the early centers of power around which two rival empires developed. The material culture was of considerable uniformity almost from the beginning. Iron also appeared at this time for ritual objects such as the throne, the scepter or cult objects. Iron weapons appeared for the first time during the great empire, albeit very rarely; the majority of the weapons were made of bronze.

Labarna I is traditionally mentioned as the founder of the empire, but it was only under his successor Ḫattušili I that it became a large empire. He moved his capital from Kuššara to Ḫattuša and led numerous campaigns. So he destroyed the city of Zalpa at the mouth of the Kızılırmak into the Black Sea, then attacked Jamchad with the capital Halpa in Syria, which controlled the caravan routes of the tin. Ḫattušili withdrew, but destroyed several cities on his way. The following year he moved to Arzawa in the west but apparently could not do much. On the contrary, the Halpa empire attacked the Hurrites (later the Mitanni empire ) with the Hittite heartland, whereupon Anatolian vassals broke away from the Hittites. After several months of fighting, the Hurrites withdrew, and most of the vassals submitted again. During his wars, Ḫattušili resorted to diplomatic means, such as in a letter to a certain Tunip-Teššup , the lord of Tikunani , in which he wanted to persuade him to undertake a joint campaign and share the booty. Again the Hittite armed forces moved to Syria and destroyed "Zaruna" and "Hassuwa", although Halpa supported them. The only thing that is certain is that Ḫattušili crossed the Taurus Mountains and then the Euphrates . Together with the panku , a kind of aristocratic assembly or councilor, he tried to regulate the succession. He made his grandson Mursili his successor. Muršili reached the upper reaches of the Tigris, from Kizzuwatna he conquered Jamchad with the capital Halpa, finally he moved in 1595 BC. BC (middle chronology) even as far as Babylon. There he captured the statue of the god Marduk and the Kassites occupied the city. Possibly they were allied with Mursili.

Muršili I was born around 1594 BC. Murdered by his brother-in-law and cupbearer Ḫantili I , which opened a series of dynastic battles. At that time, the empire was suffering from drought and rebellions and attacks by the Hurrians. Zidanta , the king's son-in-law, who had already been among the conspirators when Mursilis was murdered, murdered his son after the death of Ḫantilis I and made himself king. But Zidanta was again murdered by his own son Ammuna . During his long reign, the empire lost not only the Syrian territories, but also the Cilician plain (Kizzuwatna) and the west. The struggles within the family did not end there. In the conspiracy inspired by Ammuna's brother Zuru against the king, who commanded the royal bodyguard, the two king sons were killed. Now Ammuna's illegitimate son Ḫuzziya II came to the throne. Telipinu , a son of King Ammuna, who had to fear for his life, now overthrew the king and ascended the throne. For reasons of dynastic legitimation, he married the sister of the murdered man. He tried to end the fighting with the Telipinu decree, which established a succession to the throne, but above all prohibited the punishment of entire clans and blood revenge. He gave the panku considerable power. He also signed a contract with Kizzuwatna, which had made itself independent. The so-called Old Kingdom ended with his death.

Under Ḫantili II attacked Kaškäer from the area between Ankara and the Black Sea Ḫatti, so that the capital had to be fortified. They were shepherds whom the Hittites mistrusted so much that they were only allowed to trade in certain cities. The clashes in Syria, in which Egypt under Thutmose III. and Mitanni played important roles. Kizzuwatna in southeastern Anatolia was initially maintained as a buffer state between these great powers. At the same time, a significant cultural change became noticeable, especially since Tudḫaliya I , when the kings of Ḫatti often had a Hatti proper name and a Hurrian throne name, which is considered an indicator of "Hurritization". Tudḫaliya was married to the Hurricane Nikalmati, who apparently had a great influence on religious development.

Tudḫaliya's successor was Arnuwanda I (around 1400), who found himself embroiled in constant battles with Kaškaers and Isuwians . Ḫattuša was burned down under Tudḫaliya II and the Syrian territories were lost. Only Šuppiluliuma I was able to prevail against the attackers. He was a successful general and conspired after Tudḫaliya II around 1355 BC. Died and Tudḫaliya III. Had become great king, with part of the upper class, murdered the king and became great king himself.

Under his rule, the capital grew to three times its previous size. He was able to drive the Kaškäer away from the Hittite heartland. After this consolidation, conflicts arose with the Mitanni Empire under King Tušratta , who was in league with Egypt. Šuppiluliuma signed a treaty with Hajaša between Ḫatti and Mitanni , as well as with Ugarit , and he offered Babylon a marriage alliance. Thereupon a coalition of small states, which stood on Mitanni's side, attacked Ugarit. When Artatama II raised claims to the throne against Tušratta, he was supported by Assyria and Šuppiluliuma, who moved as far as the capital Waššukanni and plundered it. Šuppiluliuma crossed the Euphrates and besieged Karkemiš in vain. Then he subjugated other vassal states of the Mitanni. It was probably around this time that he signed a treaty with the Ugaritic king Niqmaddu II , who was under pressure from the Syrian cities. After the conclusion of this contract, Šuppiluliuma created a viceroyalty for his son Telipinu in Halpa . At that time, Egypt was busy with the Amarna Revolution under Akhenaten and therefore did not intervene. In another campaign, Qatna was destroyed, after which Egyptian chariots advanced against Kadesh, while forces of the Mitanni Empire attacked the Hittites in northern Syria. Around the same time Tušratta was overthrown by Mitanni, his son Šattiwazza fled to Šuppiluliuma, who married him to his daughter. Now one army moved to Mitanni, another against the Egyptians. The Dahamunzu affair symbolized the equality of the Hittite empire with that of the Egyptians. The Pharaoh's widow wanted to marry one of the sons of Šuppiluliuma. However, this conquered Karkemiš and set his son Šarri-Kušuh as viceroy. After another Egyptian embassy in the following year, Šuppiluliuma sent his son Zannanza to Egypt, who died, however, whereupon the Hittites attacked Egyptian Syria.

With the prisoners, however, came an epidemic to Ḫatti, which was still rampant under Mursili II ; Šuppiluliuma and his eldest son and successor Arnuwanda II were among their victims. Šarri-Kušuh succeeded in conquering Upper Mesopotamian territory in the war against Mitanni, but above all Šattiwazza was installed as king in Mittani, who concluded a treaty with Ḫatti. Telipinus' son and his descendants became kings of Halpa.

King Muršili II came to the throne young and faced numerous enemies. He hoped that through gifts and prayers he could move the gods to end the epidemics that plagued the country for twenty years. He believed that a strong state was in the spirit of the gods, and renovated many of their temples. Oracle told him that his father's moral offenses were the cause of the anger of the gods. In the first year he was attacked by the Kaškäer, whom he could never finally defeat, in the second year Assyria attacked Karkemiš and advanced into the Lower Land. However, he managed a victory over the Kaškäer and the conquest of Arzawa as far as the Aegean Sea. The remaining four kingdoms of Arzawa became vassals of the great empire. Mursili fought Pihhunija , the only king of the Kaškäer; he had unified the Kaškaers and invaded the Lower Country. The Hittites fended off an Egyptian attack in the battle of Karkemiš, whereby northern Syria remained under Hittite control. It was also possible to keep Ugarit in vassal status by signing a new treaty. Muršili conquered the apostate Karkemiš, installed the son of the late Šarri-Kušuḫ Šaḫurunuwa as governor and Sarruwa as ruler of Halap .

Muršili's son and successor Muwattalli II moved the capital to Tarḫuntašša in the Taurus Mountains, east of Antalya . He too came into conflict with Egypt. The battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC Chr. Brought no decision in the permanent conflict. Muwattalli's brother Ḫattušili III. concluded a peace treaty in 1259 . Muwattalli made a submission treaty with Alaksandu of Wilusa, which is perhaps identical to Troy. His successor Muršili III. moved the seat of his government back to the old capital. Mitanni conquered the Assyrians without Muršili offering the promised support; Muršili brusquely rejected the Assyrian peace offer. Ramses II moved in 1271 and 1269 BC. BC to Syria and conquered several Hittite cities, which were however regained by Šahurunuwa, the governor of Karkemiš.

Ḫattušili III. , the youngest son of Muršili II, overthrew Muršili III, but the legitimacy of the rulers had meanwhile been so firmly established that divine legitimacy was required to justify the overthrow, especially the Ištar of Šamuḫa , to whom the ailing king felt indebted. Kurunta , the younger brother of his predecessor, he procured rule over Tarḫuntašša.

Under his son Tudḫaliya IV there were clashes with the expanding Assyria under Tukulti-Ninurta I (ruled approx. 1233–1197 BC) A letter from Tukulti-Ninurta from Ugarit mentions a victory over a Hittite army in Upper Mesopotamia ( battle from Niḫrija ). In addition, Tarḫuntašša, where the capital was temporarily located, now became independent. On the other hand, Alašija (Cyprus) was conquered . The king apparently saw one of his most important tasks in listing and renovating all temples.

Apparently the Hittite Empire was now hit by a catastrophic famine. Pharaoh Merenptah (approx. 1212–1203) delivered grain to alleviate the misery. Between 1194 and 1186 BC Ugarit was also destroyed, Cyprus was lost, the ruler of which was the king of Ugarit, Hammurapi III. , had warned of an impending attack. However, the Ugaritian foot troops and the fleet defended the Hittite heartland and the south coast at this time, while Šuppiluliuma II led fighting in the west.

When the Hittite empire disappeared and whether there were uprisings in the capital is not known, the capital shows only minor traces of destruction. Maybe it was relocated again. Kurunta, the viceroy in Tarḫuntašša, now interfered in the battle for the great empire, but an inscription refers to a victory of Šuppiluliuma over Tarḫuntašša. Pirate fleets may have played a role in the fall of the empire, as Šikaläer ( cuneiform : ši-ka-la- (iu) -u = Šikalaju, "people of Šikala") in a letter (RS 34.129) from the Hittite great king to the city prefect published by Ugarit. They “live on ships” as it is called. The Šikaleans are probably related to the Sea Peoples , of whose occurrence Egyptian sources from the time of Merenptah and Ramses III. to report. Some of the research equates the Šikalaeans with the Šekeleš and others with the Tjekers . Where the individual sea peoples came from is very controversial in research. There are opinions, according to which they come partly from Sicily , Sardinia , Etruria , but also men from Adana and Philistines in Mukiš , north of Ugarit and in numerous other places as far as Egypt are associated with them. Mycenaean pottery of the 12th century BC BC, which was discovered in large numbers in some places in Apulia and especially in Cyprus, could refer to Mycenaean refugees. Anatolian elements in Palestine insisted that other peoples in the region were also trying to escape the unrest. The Hittite heartland was probably occupied by Kaškaers after the larger Hittite cities were abandoned or destroyed. The western Anatolian city of Troy, Layer VIIa, was probably destroyed during this period.

The Hittite culture survived until around 700 BC. In several small states in Eastern Anatolia, for example in Melid , today's Malatya , Zincirli , Karkemiš and Tabal .

South and Southeast Anatolia

In southeastern Anatolia it was mainly Tarsus and Mersin that were of great importance for the late Bronze Age. According to the previous sections, the time during the Hittite rule was divided into the Late Bronze Age I (1650–1450 BC) and II (1450–1100), with II again being divided into a Hittite and an Aegean; IIa (1450–1225) was characterized by monumental buildings of the Hittites, IIb (1225–1100) by traces of the sea peoples. Today the Late Bronze Age I is set around 100 years later, II around 40 years. While Tarsus was strongly influenced by the changes in power between Mitanni, Assyria, the Hittites and the Sea Peoples, the southeast, especially on the Tigris, was transformed from an intermediate trade zone between Mesopotamia and Anatolia to a border area between the great powers. As a result, most of the trading settlements were abandoned here, while numerous fortresses were built. At the same time, in contrast to Tarsus, the Hittite influence decreased in favor of the Syrian. At the end of the Bronze Age, the military settlements were abandoned, and large regions appear to have been uninhabited or only briefly inhabited by land occupiers. The region only recovered around 1000 BC. Chr.

Iron age

Our knowledge of the early Iron Age of Central Anatolia, which preceded the large-scale rule of Phrygia in the west and Urartu in the east, is poor due to the lack of appropriate excavations, which is all the more true for the Central Anatolian plateau. The older division into the early Iron Age, often referred to as the Dark Ages or Dark Ages , middle and late, is no longer undisputed. After these centuries, the written tradition began with increasing density, so that the contours of individual political domains are more clearly recognizable.

After the end of the Hittite Empire, the Phrygians established an empire that was established by the 8th century BC at the latest. BC ruled large parts of western and central Anatolia. Under Midas it expanded in the 2nd half of the 8th century BC. BC far to the east, like Assyrian sources especially from the time of Tiglath-Pilesers III. and Sargons II prove. Hittite successor states continued to exist in the southeast and south. Since 850 BC The kingdom of Urartu existed in eastern Anatolia (with its center at Lake Van ) .

Phrygians, Kimmerer, Lydians

At the end of the 8th century, the perhaps Scythian Cimmerians reached Anatolia. Tree ring investigations in Gordion , 100 km southwest of Ankara on the Sakarya , reveal Phrygian traces between 1071 and 740 BC. BC, with evidence of a wetter, cooler climate, which should have been beneficial to agriculture. The early Phrygian city is dated 950 to 800 BC. Dated to the Middle Phrygian between 800 and 540 BC. BC (the late Phrygian city was politically insignificant until 400 BC, but economically highly integrative). A large-scale redesign of the upper town was, as long assumed based on Assyrian and Greek sources, not suddenly ended by the cimmerians through the destruction of Gordion, but rather as early as 800 BC. By a city fire. With the incursion of the Cimmerians into central and western Anatolia at the beginning of the 7th century BC The Phrygian Empire collapsed.

It had evidently been distressed by the Lydians before. The late Iron Age, which only ended with Alexander the Great, in turn brought about extensive trade and a cultural revival. Around 680 BC The Lydians destroyed the Phrygian Empire, but in 644 BC the Lydians destroyed the Phrygian Empire. King Gyges (Guggu) was killed in the battle against the Cimmerians, as a result of which the capital Sardis was taken ( Herodotus I, 15). The Kimmerer also plundered the Ionian cities together with the Treren. It was not until around 600 that the Kimmerer was driven out by the Lydian king Alyattes II (Herodotus I, 16), the father of the famous Croesus (Kroisos). From 590 the Lydians were in conflict with the new great power of the Medes , which again drastically changed the political landscape. They had 614 BC In alliance with Babylon, the Assyrian empire and the city of Assyria were destroyed, two years later the Assyrian capital, Nineveh .