SS Andrea Doria and Luddite: Difference between pages

m Removed category "Shipwrecks" (using HotCat) |

internal reference and comment |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

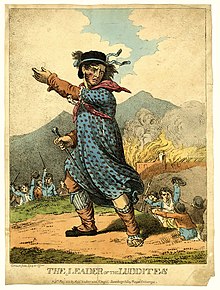

[[Image:Luddite.jpg|thumb|''The Leader of the luddites'', engraving of 1812]] |

|||

{|{{Infobox Ship Begin}} |

|||

The '''Luddites''' were a [[social movement]] of [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|British]] [[textile]] artisans in the early [[nineteenth century]] who protested—often by destroying mechanized looms—against the changes produced by the [[Industrial Revolution]], which they felt threatened their livelihood. |

|||

{{Infobox Ship Image |

|||

|Ship image=[[Image:Andreadoria02.jpg|300px]] |

|||

|Ship caption=The SS ''Andrea Doria'' |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox Ship Career |

|||

|Hide header= |

|||

|Ship name=Andrea Doria |

|||

|Ship owner=[[Italian Line]] |

|||

|Ship operator= |

|||

|Ship registry={{flag|Italy|civil}} |

|||

|Ship route= |

|||

|Ship ordered= |

|||

|Ship builder=Ansaldo Shipyards of [[Genoa]], [[Italy]] |

|||

|Ship original cost= |

|||

|Ship yard number= |

|||

|Ship way number= |

|||

|Ship laid down= |

|||

|Ship launched=June 16, 1951 |

|||

|Ship completed= |

|||

|Ship christened= |

|||

|Ship acquired= |

|||

|Ship maiden voyage=January 14, 1953 |

|||

|Ship in service= |

|||

|Ship out of service= |

|||

|Ship identification= |

|||

|Ship fate=Capsized and sank on July 25, 1956 after colliding with the [[MS Stockholm (1948)|MS ''Stockholm'']] |

|||

|Ship status= |

|||

|Ship notes= |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox Ship Characteristics |

|||

|Hide header= |

|||

|Header caption= |

|||

|Ship class=''Andrea Doria'' class [[ocean liner]] |

|||

|Ship tonnage={{GRT|29,083|first=short}} |

|||

|Ship displacement= |

|||

|Ship length={{convert|213.80|m|ftin|abbr=on}} |

|||

|Ship beam={{convert|27.50|m|ftin|abbr=on}} |

|||

|Ship height= |

|||

|Ship draught= |

|||

|Ship draft= |

|||

|Ship depth= |

|||

|Ship decks= |

|||

|Ship deck clearance= |

|||

|Ship ramps= |

|||

|Ship ice class= |

|||

|Ship sail plan= |

|||

|Ship power=Steam turbines |

|||

|Ship propulsion=Twin screws |

|||

|Ship speed={{convert|23|kn|km/h|2|abbr=on}} |

|||

|Ship capacity=1,221 passengers |

|||

|Ship crew= |

|||

|Ship notes= |

|||

}} |

|||

|} |

|||

This English historical movement has to be seen in its context of the harsh economic climate due to the [[Napoleonic Wars]], and the degrading working conditions in the new textile factories; but since then, the term Luddite has been used derisively to describe anyone opposed to [[technological progress]]<!-- "Technological progress" is NOT comparable to the "history of technology." In fact, by making it synonymous with the "history of technology, it associates the author of this conceptual link with a near-religious ascription to "technological progress." It may be necessary, at some point in Wikipedia, to create a separate article on the notion of "technological progress," since it is such an all-encompassing, dominant and impacting idea on global behavior and dogma. ~~~~ --> and [[technological change]]. |

|||

'''SS ''Andrea Doria'' ''' was an [[ocean liner]] for the [[Italian Line]] (Società di navigazione Italia) home ported in [[Genoa]], [[Italy]]. Named after the 16th-century [[Genoa|Genoese]] admiral [[Andrea Doria]], the ''Andrea Doria'' had a [[gross tonnage]] of 29,100 and a capacity of about 1,200 passengers and 500 crew. For a country attempting to rebuild its economy and reputation after [[World War II]], the ''Andrea Doria'' was an icon of Italian national pride. Of all Italy's ships at the time, ''Andrea Doria'' was the largest, fastest and supposedly safest. Launched on June 16, 1951, the ship undertook its [[maiden voyage]] on January 14, 1953. |

|||

The Luddite movement, which began in 1811, took its name from the fictive [[Ned Ludd]]. For a short time the movement was so strong that it clashed in battles with the [[British Army]]. Measures taken by the government included a mass trial at [[York]] in 1812 that resulted in many [[execution]]s and [[penal transportation]]. |

|||

On July 25, 1956, approaching the coast of [[Nantucket, Massachusetts|Nantucket]], [[Massachusetts]] bound for [[New York City]], the ''Andrea Doria'' collided with the eastward-bound [[MS Stockholm (1948)|MS ''Stockholm'']] of the [[Swedish American Line]] in what became one of history's most famous [[list of shipwrecks|maritime disasters]]. Struck in the side, the ''Andrea Doria'' immediately started to list severely to starboard, which left half of her [[Lifeboat (shipboard)|lifeboat]]s unusable. The consequent shortage of lifeboats might have resulted in significant loss of life, but improvements in communications and rapid responses by other ships averted a disaster similar in scale to the [[RMS Titanic|''Titanic'']] disaster of 1912. 1660 passengers and crew were rescued and survived, while 46 people died as a consequence of the collision.<ref name="lostliners">{{cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/lostliners/chart.html |title=PBS Online - Lost Liners - Comparison Chart |accessdate=2007-12-11 |publisher=[[PBS]]}}</ref> The evacuated luxury liner capsized and sank the following morning. |

|||

The principal objection of the Luddites was the introduction of new wide-framed automated looms that could be operated by cheap, relatively unskilled labour, resulting in the loss of jobs for many skilled textile workers. |

|||

The incident and its aftermath were heavily covered by the news media. While the rescue efforts were both successful and commendable, the cause of the collision and the loss of the ''Andrea Doria'' afterward generated much interest in the media and many lawsuits. Largely because of an out-of-court settlement agreement between the two shipping companies during hearings immediately after the disaster, no determination of the cause(s) was ever formally published. Although greater blame appeared initially to fall on the Italian liner, more recent discoveries have indicated that a misreading of radar on the Swedish ship may have initiated the collision course, leading to some errors on both ships and resulting in disaster. |

|||

The ''Andrea Doria'' was the last major transatlantic passenger vessel to sink before [[Fixed-wing aircraft|aircraft]] became the preferred method of travel. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The original Luddites claimed to be led by one "King Ludd" (also known as "General Ludd" or "Captain Ludd") whose signature appears on a "workers' [[manifesto]]" of the time. King Ludd was based on the earlier [[Ned Ludd]], who some believed to have destroyed two large [[stocking frame]]s in the village of [[Anstey, Leicestershire]] in 1779. Naturally, in a situation where machine breaking could lead to heavy penalties or even execution, the use of an imaginary name was an understandable tactical necessity. |

|||

=== Features === |

|||

[[Image:DoriaStern.jpg|thumb|right|The model of the ''Andrea Doria'']] |

|||

''Andrea Doria'' had a length of 212 [[metre|m]] <!--PLEASE ORIGINAL UNITS OF MEASURE FIRST-->(697 [[foot (unit of length)|feet]]), a [[Beam (nautical)|beam]] of 27 m (90 ft), and a [[gross tonnage]] of 29,100.<ref name="lostliners"/> The propulsion system consisted of steam [[turbine]]s attached to twin [[Propeller|screw]]s, enabling the ship to achieve a service speed of {{convert|23|kn|km/h}}, with a top speed of {{convert|26|kn|km/h}}. ''Andrea Doria'' was not the largest vessel nor the fastest of its day: those distinctions went to the [[RMS Queen Elizabeth|RMS ''Queen Elizabeth'']] and the [[SS United States|SS ''United States'']], respectively. Instead, ''Andrea Doria'' was designed for luxury by the famous Italian architect, Minoletti. |

|||

Research by historian Kevin Binfield<ref>Binfield, Kevin. ''Luddites and Luddism: History, Texts Interpretation''. http://campus.murraystate.edu/academic/faculty/kevin.binfield/luddites/LudditeHistory.htm Accessed 4 June 2008.</ref> is particularly useful in placing the Luddite movement in historical context—as organised action by stockingers had occurred at various times since 1675, and the present action had to be seen in the context of the hardships suffered by the working class during the Napoleonic Wars. |

|||

Since it sailed the southern Atlantic routes, ''Andrea Doria'' was the first ship to feature three outdoor [[swimming pool]]s, one for each class (first, cabin, and tourist). The ship was capable of accommodating 218 [[first class travel|first-class]] passengers, 320 [[cabin-class]] passengers, and 703 [[tourist-class]] passengers, and 563 [[crew members|crew]]<ref name="lostliners"/> on ten decks.<ref>[http://www.andreadoria.org/DeckPlans/DeckPlan.htm Passenger Accommodation Deck Plan]. ''Andrea Doria: Tragedy and Rescue at Sea''.</ref> With over [[United States Dollar|$]]1 million spent on artwork and the decor of the cabins and public rooms, including a life-size statue of Admiral Doria, many consider the ship to have been one of the most beautiful ocean liners ever built. |

|||

[[Image:Stocking frame diagram.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The stocking frame]] |

|||

The movement began in [[Nottingham]] in 1811 and spread rapidly throughout England in 1811 and 1812. Many [[wool]] and [[cotton]] [[mill (factory)|mill]]s were destroyed until the British government harshly suppressed the movement. The Luddites met at night on the moors surrounding the industrial towns, practising drills and manoeuvres and often enjoyed local support. The main areas of the disturbances were [[Nottinghamshire]] in November 1811, followed by the [[West Riding of Yorkshire]] in early 1812 and [[Lancashire]] from March 1813. Battles between Luddites and the military occurred at Burton's Mill in [[Middleton, Greater Manchester|Middleton]], and at [[Westhoughton Mill]], both in [[Lancashire]]. It was rumoured at the time that [[agent provocateur|agents provocateurs]] employed by the magistrates were involved in provoking the attacks.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Magistrates and food merchants were also objects of death threats and attacks by the anonymous King Ludd and his supporters. Some industrialists even had secret chambers constructed in their buildings, which may have been used as a hiding place.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/leicestershire/4791069.stm BBC NEWS | England | Leicestershire |Workmen discover secret chambers<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

"Machine breaking" (industrial [[sabotage]]) was subsequently made a [[capital crime]] by the Frame Breaking Act ([[George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron|Lord Byron]], one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites, famously spoke out against this legislation), and 17 men were executed after an 1813 [[trial (law)|trial]] in [[York]]. Many others were [[penal transportation|transported as prisoners]] to [[Australia]]. At one time, there were more British troops fighting the Luddites than [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon I]] on the [[Iberian Peninsula]].{{Fact|date=October 2007}} Three Luddites ambushed and murdered a mill-owner (William Horsfall from Ottiwells Mill in [[Marsden,_West_Yorkshire|Marsden]]) at [[Crosland Moor]], [[Huddersfield]]; the Luddites responsible were hanged in York, and shortly thereafter 'Luddism' waned.<!--any dates on this event?--> |

|||

===Safety and seaworthiness=== |

|||

[[Image:Andrea Doria poster.jpg|thumb|left|An Italian poster announcing the entrance in service of the "greatest, latest and fastest Italian liner".]] |

|||

The ship was also considered one of the safest ever built. Equipped with a [[double hull]], ''Andrea Doria'' was divided into eleven [[bulkhead (partition)|watertight compartments]]. Any two of these could be filled with water without endangering the ship’s safety. The ''Andrea Doria'' also carried enough [[Lifeboat (shipboard)|lifeboat]]s to accommodate all passengers and crew. Furthermore, the ship was equipped with the latest early warning [[radar]]. However, and despite its technological advantages, the ship had serious flaws involving its seaworthiness and safety. |

|||

However, the movement can also be seen as part of a rising tide of English working-class discontent in the early 19th century (see also, for example, the [[Pentrich, Derbyshire|Pentrich Rising]] of 1817, which was a general uprising, but led by an unemployed Nottingham stockinger, and probable ex-Luddite, [[Jeremiah Brandreth]]). An agricultural variant of Luddism, centering on the breaking of threshing machines, was crucial to the widespread [[Swing Riots]] of 1830 in southern and eastern England. |

|||

Confirming predictions derived from model testing during the design phase, the ship developed a huge [[Wiktionary:list#Etymology 4|list]] when hit by any significant force. This was especially apparent during its maiden voyage, when ''Andrea Doria'' listed twenty-eight [[degree (angle)|degree]]s after being hit by a [[Ocean surface wave|large wave]] off [[Nantucket]]. The ship's tendency to list was accentuated when the fuel tanks were nearly empty, which was usual at the end of a voyage.<ref name="othfors">Othfors, Daniel. Andrea Doria. ''[http://www.greatoceanliners.net/ The Great Ocean Liners]''.</ref> |

|||

In recent years, the terms Luddism and Luddite or Neo-Luddism and Neo-Luddite have become synonymous with anyone who opposes the advance of [[technology]] due to the cultural and socioeconomic changes that are associated with it. |

|||

This stability issue would become a focus of the investigation after the sinking, as it was a factor in both the capsizing and the crew's inability to lower the port-side lifeboats. The bulkheads of the watertight compartments extended only up to the top of A Deck, and a list greater than 20 degrees allowed water from a flooded watertight compartment to pass over its top into adjacent compartments. In addition, the design parameters allowed the lowering of the lifeboats at a maximum 15-degrees list. Beyond 15 degrees, up to half of the lifeboats could not be deployed. |

|||

==Criticism of Luddism== |

|||

===Construction and maiden voyage=== |

|||

The term "[[Luddite fallacy]]" has become a concept in [[neoclassical economics]] reflecting the belief that labour-saving technologies (i.e., technologies that increase output-per-worker) increase unemployment by reducing demand for labour. The "fallacy" lies in assuming that employers will seek to keep production constant by employing a smaller, more productive workforce instead of allowing production to grow while keeping workforce size constant.<ref>{{cite book |last=Easterly |first=William |authorlink=William Easterly |title=The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics |year=2001 |publisher=[[MIT Press]] |location=[[Cambridge, Massachusetts]] |isbn=0-262-55042-3 |pages=53-54}}</ref> |

|||

At the end of [[World War II]], Italy had lost half its merchant fleet through wartime destruction and Allied forces' seeking [[war reparations]]. The losses included the [[SS Rex|SS ''Rex'']], a former [[Blue Riband]] holder. Furthermore, the country was struggling with a collapsed economy.<ref>[http://www.lostliners.com/Liners/Italia/Andrea_Doria/ship.html Andrea Doria]. ''LostLiners.com''.</ref> To show the world that the country had recovered from the war and to reestablish the nation's pride, the Italian Line commissioned two new vessels of similar design in the early 1950s. The first was to be named ''Andrea Doria'', after the 16th-century [[Genoa|Genoese]] admiral [[Andrea Doria]]. The second vessel, which was launched in 1953, was to be named ''[[SS Cristoforo Colombo|Cristoforo Colombo]]'' after explorer [[Christopher Columbus]]. |

|||

==E. P. Thompson's view of Luddism== |

|||

The ''Andrea Doria'' started as Yard No. 918 at Ansaldo Shipyard in [[Genoa]]. On February 9, 1950, the ship's keel was laid on the No. 1 [[slipway]], and on June 16, 1951, the ''Andrea Doria'' was launched. During the ceremony, the ship's hull was blessed by [[Giuseppe Siri]], Cardinal [[Archbishop of Genoa]], and christened by Mrs. Giuseppina Saragat, wife of the former Minister of the Merchant Marine [[Giuseppe Saragat]]. However, amid reports of machinery problems during sea trials, the ''Andrea Doria's'' maiden voyage was pushed back from December 14, 1952, to January 14, 1953.<ref>[http://www.andreadoria.org/TheShips/Default.htm The Ships: Andrea Doria]. ''Andrea Doria: Tragedy and Rescue at Sea''.</ref> |

|||

In his work on English history, ''[[The Making of the English Working Class]]'', [[E. P. Thompson]] presented an alternative view of Luddite history. He argues that Luddites were not opposed to new technology in itself, but rather to the abolition of set prices and therefore also to the introduction of the [[free market]]. |

|||

During the ship's maiden voyage it encountered heavy storms on the final approach to New York and was delayed by minutes. Nevertheless, the ''Andrea Doria'' completed its maiden voyage on January 23 and received a welcoming delegation which included [[Mayors of New York City|New York Mayor]] [[Vincent R. Impellitteri]]. Afterwards, ''Andrea Doria'' became one of Italy's most popular and successful ocean liners as it was always filled to capacity. By mid-1956, it was making its one-hundredth crossing of the Atlantic. |

|||

Thompson argues that it was the newly-introduced economic system that the Luddites were protesting. For example, the Luddite song, "General Ludd's Triumph": |

|||

==Final voyage== |

|||

:The guilty may fear, but no vengeance he aims |

|||

=== A collision course === |

|||

:At the honest man's life or Estate |

|||

On the evening of Wednesday, July 25, 1956, the ''Andrea Doria'', commanded by [[Captain]] [[Piero Calamai]], carrying 1,134 passengers and 572 crew members, was heading west toward [[New York City|New York]]. It was the last night out of a transatlantic crossing from Genoa that began on July 17. The ship was expected to dock in New York the next morning. |

|||

:His wrath is entirely confined to wide frames |

|||

:And to those that old prices abate |

|||

"Wide frames" were the cropping frames, and the old prices were those prices agreed by custom and practice. Thompson cites the many historical accounts of Luddite raids on workshops where some frames were smashed whilst others (whose owners were obeying the old economic practice and not trying to cut prices) were left untouched. This would clearly distinguish the Luddites from someone who was today called a luddite; whereas today a luddite would reject new technology because it is new, the Luddites were acting from a sense of self-preservation rather than merely fear of change. |

|||

==The Luddites in fiction== |

|||

At the same time, [[MS Stockholm (1948)|MS ''Stockholm'']], a smaller passenger liner of the [[Swedish American Line]], had departed New York about midday, heading east across the North Atlantic Ocean toward [[Gothenburg]], [[Sweden]]. The ''Stockholm'' was commanded by Captain Harry Gunnar Nordenson, though [[Third Officer]] Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen was in command on the [[bridge (ship)|bridge]] at the time. The ''Stockholm'' was following its usual course east to [[Lightship Nantucket|Nantucket Lightship]], making about 18 knots (33 km/h) with clear skies. Carstens estimated visibility at 6 miles (11 km in terms of nautical miles). |

|||

*''[[Shirley (novel)|Shirley]]'' by [[Charlotte Brontë]], a [[social novel]] set against the backdrop of the Luddite riots in the Yorkshire textile industry in 1811–1812. |

|||

*''[[The Difference Engine]]'' by [[William Gibson]] and [[Bruce Sterling]], a novel speculating on what might have been had [[Charles Babbage]] completed his [[Difference Engine]] during the [[Industrial Revolution]]. |

|||

*''[[Mark of the Rani]]'', a story from the 1985 season of the British TV program [[Doctor Who]] is set during the height of the Luddite movement. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

As the ''Stockholm'' and the ''Andrea Doria'' were approaching each other head-on, in the well-used shipping corridor, the westbound ''Andrea Doria'' had been traveling in [[fog|heavy fog]] for hours. The captain had reduced speed slightly (from 23 to 21.8 knots), activated the ship's fog-warning whistle, and had closed the watertight doors, all customary precautions while sailing in such conditions. However, the eastbound ''Stockholm'' had yet to enter what was apparently the edge of a fog bank and was apparently unaware of it. (The waters of the North Atlantic south of [[Nantucket Island]] are frequently the site of intermittent fog as the cold [[Labrador Current]] encounters the [[Gulf Stream]].) |

|||

*[http://campus.murraystate.edu/academic/faculty/kevin.binfield/luddites/LudditeHistory.htm ''Luddites and Luddism''] (Kevin Binfield, ed.) |

|||

==References== |

|||

As the two ships approached each other, at a combined speed of {{convert|40|kn|km/h}}, each was aware of the presence of another ship but was guided only by radar; they apparently misinterpreted each others' courses. There was no radio communication between the two ships. |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

==See also== |

|||

The original inquiry established that in the critical minutes before the collision, ''Andrea Doria'' gradually steered to port (left), attempting a starboard-to-starboard meeting, while the ''Stockholm'' turned about 20 degrees to its starboard (right), an action intended to widen the passing distance of a port-to-port meeting. In fact, they were actually steering ''towards'' each other — narrowing, rather than widening, the passing distance. Compounded by the extremely thick fog that enveloped the ''Doria'' as the ships approached each other, the ships were quite close by the time visual contact had been established. By then, crew realized that they were on a collision course, but despite last-minute maneuvers, they were unable to avoid that collision. |

|||

*[[Antimodernism]] |

|||

*[[Critique of technology]] |

|||

In the last moments before impact, the ''Stockholm'' turned hard to the starboard and was in the process of reversing its propellers attempting to stop. The ''Doria'', remaining at its cruising speed of almost {{convert|22|kn|km/h}} engaged in a hard turn to port, its Captain hoping to outrun the collision. At approximately 11:10 <small>PM</small>, the two ships collided. |

|||

*[[Jacquard loom]] |

|||

*[[Neo-Luddism]] |

|||

[[Image:Andrea Doria at Dawn.jpg|275px|right|thumb|SS ''Andrea Doria'' the morning after the collision with the SS ''Stockholm'' in fog off Nantucket Island.]] |

|||

*[[Peterloo]] |

|||

*[[Propaganda of the deed]] |

|||

=== Impact and penetration === |

|||

*[[Sabotage]] |

|||

When ''Andrea Doria'' and the ''Stockholm'' collided at almost a 90-degree angle, the ''Stockholm''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> sharply raked [[ice breaker|ice breaking]] prow pierced ''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> starboard side approximately midway of its length. It penetrated three passenger cabins, numbered 52, 53, and 54 to a depth of nearly 40 feet (12 m), and the keel. The collision smashed many occupied passenger cabins and, at the lower levels, ripped open several of ''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> watertight compartments. The gash pierced five fuel tanks on ''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> starboard side and filled them with 500 tons of seawater. Meanwhile, air was trapped in the empty tanks on the port side, contributing to a severe, uncorrectable list. The ship's large fuel tanks were mostly empty at the time of the collision, since the ship was nearing the end of its voyage. |

|||

*[[Swing Riots]] |

|||

*[[Technophobia]] |

|||

Meanwhile, on the bridge of the ''Stockholm'', immediately after the impact, engines were placed at FULL STOP, and all watertight doors were closed. The ships were intertwined about 30 seconds. As they separated, the smashed bow of the stationary ''Stockholm'' was dragged aft along the starboard side of the ''Doria'', which was still moving forward, adding more gashes along the side. The two ships then separated, and the ''Doria'' moved away into the heavy fog. Initial radio distress calls were sent out by each ship, and in that manner, they learned each others' identities. The world soon became aware that two large ocean liners had collided. |

|||

*[[Technorealism]] |

|||

*[[Techno-utopianism]] |

|||

This was the [[SOS]] sent by the ''Andrea Doria'': |

|||

"SOS DE ICEH SOS HERE AT 0320 GMT LAT. 40.30 N 69.53 W |

|||

NEED IMMEDIATE ASSISTANCE" |

|||

=== Assessing damage and imminent danger === |

|||

Immediately after the collision, ''Andrea Doria'' began to take on water and started to list severely to starboard. Within minutes, the list was at least 18 degrees. After the ships separated, the Captain quickly brought the engine controls to FULL STOP. Many people believe that one of the watertight doors to the engine room was missing, though this issue was later determined to be moot (''see Later Investigations and Study below''). Much more importantly, however, crucial stability was lost by the earlier failure, during routine operations, to [[sailing ballast|ballast]] the mostly empty fuel tanks as the builders had specified. (Filling the tanks with seawater as the fuel was emptied would have resulted in more costly procedures to refuel when port was reached). Owing to the immediate rush of seawater flooding the starboard tanks, and the fact that the port tanks were empty because the crossing was almost over, the list was greater than would otherwise have been the case. As it increased over the next few minutes, to 20 degrees or more, Captain Calamai realized there was no hope for his ship unless the list could be corrected. |

|||

In the engine room, engineers attempted to pump water out of the flooding starboard tanks to no avail. There was only a small amount of remaining fuel, and the intakes to pump seawater into the port tanks were now high out of the water, making that procedure to attempt to level the ship impossible. Progressive loss of generators due to flooding as the water rose in the engine room reduced the ability to pump even more. |

|||

On the ''Stockholm'', the entire bow was crushed, including some crew cabins. Initially, the ship was dangerously down by the bow, but emptying the freshwater tanks soon raised the bow to within four inches (102 mm) of normal. |

|||

A quick survey determined that the major damage did not extend aft beyond the bulkhead between the first and second watertight compartments. Thus, despite being a bit down at the bow, and having its first watertight compartment flooded, the ship was soon determined to be stable and in no imminent danger of sinking. |

|||

=== Casualties === |

|||

Eventually, it was determined that forty-six passengers of ''Andrea Doria'' were killed in the collision area of their ship, among them Camille Cianfarra, a longtime foreign correspondent for ''[[The New York Times]]''.<ref>http://nytco.com/company-timeline-1941.html</ref> Five crew members of the ''Stockholm'' whose cabins were located in the bow area and were in the impact area of their ship at the time of the collision also perished: three during the collision, and two more later from mortal injuries. The deaths of two ''Doria'' passengers were related to the rescue operation. There were hundreds of injuries, some from the collision and some sustained on the listing liner and during the evacuation process. |

|||

After the ships had separated, as ''Stockholm'' crew members were beginning to survey the damage, on the deck of the ''Stockholm'' aft of the wrecked bow they discovered 14-year-old [[Linda Morgan]] without any major injury. It was soon determined that she had been an ''Andrea Doria'' passenger, had miraculously survived the impact, and had been somehow propelled far onto the ''Stockholm'' deck. Her [[half sister]] Joan, who had been sleeping in Cabin 52 with her on ''Andrea Doria'', had perished, as did her stepfather. Camille Cianfarra had been in an adjacent cabin with her mother, who was seriously injured but survived and had to be extricated. The body of another ''Doria'' passenger, a middle-aged woman, was also observed lodged in an inaccessible area of the wreckage of the Stockholm's bow. |

|||

A search went underway for several missing Stockholm crewmen. It was determined that five had perished, and those injured were taken to the ship's hospital. |

|||

On the ''Andrea Doria'', there were serious injuries and passengers trapped in the wreckage of cabins in the impact area and many injuries from falls and so forth from other points around the ship. The lowest decks in the impact area became submerged immediately after the collision, and many of the casualties were members of immigrant families who were presumed to have drowned. A number of injured persons received medical treatment, but more significantly, it soon became clear to those on the bridge that it would be necessary to evacuate the ''Andrea Doria'', a hazardous activity under the best conditions. Due to the list, the evacuation would prove far more difficult than perhaps any shipbuilder had envisioned. |

|||

=== Difficult, successful rescue operations === |

|||

[[Image:Stockholm following Andrea Doria collision.jpg|250px|left|thumb|The {{MS|Stockholm|1948}} heads to New York after colliding with ''Andrea Doria'', [[July 26]], [[1956]]. Note the severely damaged prow.]] |

|||

On ''Andrea Doria'', the decision to abandon ship was made within 30 minutes of impact. A sufficient number of lifeboats for all of the passengers and crew were positioned on each side of the Boat Deck. Procedures called for lowering the lifeboats to be fastened alongside the glass-enclosed Promenade Deck (one deck below), where evacuees could step out windows directly into the boats, which would then be lowered down to the sea. |

|||

However, it was soon determined that half of the lifeboats, those on the port side, were unlaunchable due to the severe list, which left them high in the air. To make matters worse, the list also complicated normal lifeboat procedures on the starboard side. Instead of loading lifeboats at the side of the Promenade Deck and then lowering them into the water, it would be necessary to lower the boats empty, and somehow get evacuees down the exterior of the ship to water level to board. This was eventually accomplished through ropes, jacob's ladders, and a large fishing net. Some passengers panicked and threw children to rescuers below or jumped overboard themselves. |

|||

A distress message was relayed to other ships by radio, making it clear that additional lifeboats were urgently needed. While other ships nearby were en route, the captain of the ''Stockholm'', having determined that his ship was not in any imminent danger of sinking, and after being assured of the safety of his mostly sleeping passengers, sent some of his lifeboats to supplement the starboard boats from the ''Andrea Doria.'' In the first hours, many survivors transported by lifeboats from both ships were taken aboard the ''Stockholm.'' |

|||

Unlike the ''[[RMS Titanic|Titanic]]'' tragedy 44 years earlier, several other non-passenger ships relatively close by did receive and respond to the call for help. Radio communications included relays from the other ships as the ''Doria's'' batteries had limited range. There was also coordination on land by the [[United States Coast Guard]] from a center in New York. |

|||

A major turning point in the rescue effort was the decision by Baron [[Raoul de Beaudean]], Captain of the [[SS Ile de France|SS ''Ile de France'']], a large eastbound [[French Line]] passenger liner, which had passed the westbound ''Andrea Doria'' many hours earlier, to turn back to assist. The French liner had sufficient capacity to accommodate the many extra passengers, and was fully-provisioned, only a day out of New York on its planned eastbound crossing. While Captain de Beaudean steamed through the fog back west to the scene, his crew prepared to launch its lifeboats and receive those to be rescued. |

|||

Arriving at the scene less than 3 hours after the collision, as he neared, Captain de Beaudean became concerned about navigating his huge ship safely among the two wounded liners, other responding vessels, lifeboats and possibly even people in the water. Then, just as the ''Ile de France'' arrived, the fog lifted, and he was able to position his ship in such a way that the starboard side of the ''Doria'' was somewhat sheltered. He ordered all exterior lights of the ''Ile'' to be turned on. The sight of the illuminated ''Ile de France'' was a great emotional relief to many participants, crews and passengers alike. |

|||

The ''Ile'' managed to rescue the bulk of the remaining passengers by shuttling its ten lifeboats back and forth to the ''Andrea Doria'', and receiving lifeboat loads from those of the other ships already at the scene (as well as the starboard boats from the ''Doria''). Some passengers on the ''Ile de France'' gave up their cabins to be used by the wet and tired survivors. Many other acts of kindness were reported by grateful survivors. |

|||

Assisted also by several smaller ships which had responded, the ''Doria'' was completely evacuated by daybreak. As a result, loss of life was limited to those killed or mortally injured on the two ships during the actual collision and the immediate aftermath. One child, four-year-old Norma Di Sandro, who suffered a head injury when dropped by her father into a waiting lifeboat, did not recover and died later at a Boston hospital. Also, an ''Andrea Doria'' passenger, having worked strenuously to help others during the rescue, suffered a fatal heart attack the next day aboard the ''Stockholm'' while it was returning to New York. |

|||

Shortly after daybreak, the little girl and four seriously-injured ''Stockholm'' crewmen were airlifted from that ship at the scene by helicopters sent by the Coast Guard and [[U.S. Air Force]]. A number of passengers and some crew were hospitalized upon arrival in New York. |

|||

=== ''Andrea Doria'' capsizes and sinks === |

|||

[[Image:Andrea Doria USCG 1.jpg|250px|right|thumb|SS ''Andrea Doria'' awaiting her impending fate the morning after the collision in the Atlantic Ocean, [[July 26]], [[1956]].]] |

|||

Once the evacuation was complete, the captain of the ''Andrea Doria'' shifted his attention to the possibility of towing it to shallow water. However, it was clear to those watching helplessly at the scene that the stricken ocean liner was continuing to roll on its side. |

|||

After all the survivors had been transplanted onto various rescue ships bound for New York, the Doria's remaining crew began to disembark—forced to abandon the ship. By 9:00 a.m. even Captain Calamai was in a rescue boat. The sinking began at 9:45 a.m. and by 10:00 that morning the Doria was on her side at a right angle to the sea. The Doria fully disappeared from sight at 10:09—almost exactly eleven hours after the collision with the Stockholm took place.<ref>http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/case_andreadoria/index.html</ref> |

|||

The starboard side dipped into the ocean and the three swimming pools were seen refilling with water. As the bow slid under, the stern rose slightly, and the propellers and shafts were visible. As the port side slipped below the waves, some of the unused lifeboats ripped free of their davits. It was recorded that ''Andrea Doria'' finally sank 11 hours after the collision, at 10:09 <small>AM</small> on July 26. The wreck is located at {{coord|40.49167|-69.85000}}<ref name=autogenerated1>http://www.carlonordling.se/doria/doria.html</ref> so the ship had drifted {{convert|1.58|nmi|km}} from the point of the collision in the following 11 hours. Spectacular aerial photography of the stricken ocean liner capsizing and sinking [[1957 Pulitzer Prize|won]] a [[Pulitzer Prize]] in 1957 for Harry A. Trask of the ''Boston Traveler'' newspaper. |

|||

=== Return to New York; families === |

|||

Due to the scattering of ''Andrea Doria'' passengers and crew among the various rescue vessels, some families were separated during the collision and rescue. It was not clear who was where, and whether or not some persons had survived, until after all the ships with survivors arrived in New York. This included six different vessels, including the heavily damaged ''Stockholm'', which was able to steam back to New York under its own power with a [[United States Coast Guard]] escort, but arrived later than the other ships. |

|||

During the wait, [[American Broadcasting Company|ABC Radio Network]] news commentator [[Edward P. Morgan]], based in New York City, broadcast a professional account of the collision, not telling listeners that his 14-year-old daughter had been aboard ''Andrea Doria'' and feared dead. He did not know that [[Linda Morgan]], who was soon labeled the "miracle girl," was alive and aboard the ''Stockholm.'' The following night, after learning the good news, his emotional broadcast became one of the more memorable in radio news history. |

|||

Among ''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> passengers were [[Hollywood]] actress [[Ruth Roman]] and her four-year-old son. In the 1950 film ''[[Three Secrets]]'', Roman had portrayed a distraught mother waiting to learn whether or not her child had survived a plane crash. She and her son were separated from each other during the collision and evacuation. Rescued, Roman had to wait to learn her child's fate which resulted in a media frenzy for photos as she waited at the pier in [[New York City]] for her child's safe arrival aboard one of the rescue ships. Actress [[Betsy Drake]], wife of movie star [[Cary Grant]] also escaped from the sinking liner, as did Philadelphia mayor [[Richardson Dilworth]] and songwriter Mike Stoller (of the team [[Leiber and Stoller]]). |

|||

Assisted by the [[American Red Cross]] and news photographers, the frantic parents of four-year old Norma Di Sandro learned that their injured daughter had been airlifted from the ''Stockholm'' to a hospital in [[Boston, Massachusetts|Boston]], [[Massachusetts]], where the previously unidentified little girl had undergone surgery for a fractured skull. They drove all night from New York to Boston, with police escorts provided to their convoy in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. When they arrived, the child was still unconscious and the doctors said all that could be done was wait to see if she woke up. The little girl never regained consciousness, and succumbed to her injuries. |

|||

Other families also had their hopes of seeing loved ones again dashed, especially those who were meeting members of several young families immigrating to the United States in hope of new lives. |

|||

The sinking produced a footnote in automotive history, as it resulted in the loss of the [[Chrysler Norseman]], an advanced "one-off" prototype car which had been built for [[Chrysler]] by [[Ghia]] in Italy. The Norseman had been announced as a major attraction of the 1957 auto show circuit. However, it had not been shown to the public prior to the disaster, and was lost, along with other cars in the ''Doria's'' 50-car garage including a Rolls Royce. |

|||

== Aftermath == |

|||

=== Litigation and determination of fault: 1956–57 === |

|||

There were several months of hearings in New York City in the aftermath of the collision. Prominent maritime attorneys represented both the ships' owners. Dozens of attorneys represented victims and families of victims. Officers of both ship lines had testified, including the officers in charge of each ship at the time of the collision, with more scheduled to appear later when an [[out-of-court settlement]] was reached, and the hearings ended abruptly. |

|||

Both shipping lines contributed to a settlement fund for the victims. Each line sustained its own damages. For the Swedish-American Line, damages were estimated at $2 million, half for repairs to ''Stockholm''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> bow, and half for lost business during repairs. The Italian Line sustained a loss of ''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> full value, estimated to be $30 million. |

|||

A U.S. Congressional hearing was also held, and provided some determinations, notably about the lack of ballasting specified by the builders during the fatal voyage and the resulting lack of seaworthiness of the ''Andrea Doria'' after the collision. |

|||

While heavy fog would be the main reason given as the cause of the accident, and it is not disputed that intermittent and heavy fog are both frequent and challenging conditions for mariners in that part of the ocean, these other factors have been cited: |

|||

#''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> officers had not followed proper radar procedures or used the plotting equipment available in the chartroom adjacent to the bridge of their ship to calculate the position and speed of the other (approaching) ship. Thus, they failed to realize ''Stockholm''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> size, speed, and course. |

|||

#''Andrea Doria'' had not followed the proper "[[International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea|rules of the road]]"<ref>[http://www.navcen.uscg.gov/mwv/navrules/rotr_online.htm Navigation Rules Online (July 12, 2005)]. ''U.S. Coast Guard - Navigation Center''.</ref> in which a ship should turn to right (to ''starboard'') in case of a possible head-on crossing at sea. As the ''Stockholm'' turned ''right'', ''Andrea Doria'' turned ''left'' (to ''port''), closing the circle instead of opening it. Beyond a certain point, it became impossible to avoid a collision. |

|||

#Captain Calamai of ''Andrea Doria'' was deliberately speeding in heavy fog, an admittedly common practice on passenger liners. The navigation rules required speed to be reduced during periods of limited visibility to a stopping distance within half the distance of visibility. As a practical matter, this would have meant reducing the speed of the ship to virtually zero in the dense fog. |

|||

#The ''Stockholm'' and the ''Andrea Doria'' were experiencing different weather conditions immediately prior to the collision. The collision occurred in an area of the northern [[Atlantic Ocean]] off the coast of [[Massachusetts]] where heavy and intermittent fog is common. Although ''Andrea Doria'' had been engulfed in the fog for several hours, the ''Stockholm'' had only recently entered the bank and was still acclimating to atmospheric conditions. The officer in charge of the ''Stockholm'' incorrectly assumed that his inability to see the other vessel was due to conditions other than fog, such as the other ship being a very small fishing vessel or a ''blacked-out'' warship on maneuvers. He testified that he had no idea it was another passenger liner speeding through fog. |

|||

#The Andrea Doria fuel tanks were half empty and not pumped with seawater ballast in order to stabilize the ship, in accordance with the Italian Line's procedures. This contributed to the pronounced list following the collision, the inability of the crew to pump water into the port fuel tanks to right the ship, and the inability to use the port lifeboats for the evacuation. |

|||

#There was also perhaps a "missing" watertight door between bulkheads near the engine room, which was thought to have contributed to ''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> problems. |

|||

Both lines had an incentive to limit the public discussion of ''Andrea Doria'' <nowiki>'s</nowiki> structural and stability problems. ''Stockholm''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> owners had another new ship, the ''[[MS Gripsholm|Gripsholm]]'', under construction at Ansaldo Shipyard in Italy.<ref name="othfors"/> ''Andrea Doria''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> designers and engineers had been scheduled to testify, but the hearings were abruptly concluded before their testimony could be heard due to the settlement agreement. |

|||

=== Resulting reforms === |

|||

The ''Andrea Doria-Stockholm'' collision led to several rule changes in the immediate years following the incident to avoid a recurrence. Shipping lines were required to improve training on the use of radar equipment. Also, approaching ships were required to make radio contact with one another. Both ships saw each other on their radar systems and attempted to turn. Unfortunately, one of the radar systems was incorrect and this resulted in the collision. |

|||

=== Later investigations and study === |

|||

Unanswered questions about the tragedy, and questions of cause and blame, have intrigued observers and haunted survivors for almost 50 years. The fact that the ''Andrea Doria'' was speeding in heavy fog and questions about its seaworthiness arose at the time. Captain Calamai never assumed another command. However, largely because of the out-of-court settlement agreement between the two shipping companies ended the fact finding which was taking place in the hearings immediately after the disaster, no resolution of the cause(s) was ever formally accomplished. This has led to continued development of information and a search for greater understanding, aided by newer technologies in over half a century since the disaster. |

|||

Recent discoveries using computer animation and newer undersea diving technology and have shed additional light on some aspects. |

|||

* Many years later, scientific study of the actions of the two crews indicated a probability that the [[First Mate]] on the ''Stockholm'' misinterpreted his radar in the minutes prior to the impact. Recent studies and computer simulations carried out by Captain Robert J. Meurn of the [[United States Merchant Marine Academy]] and based on the findings of John C. Carrothers suggest ''Stockholm'' Third Officer Carstens-Johannsen misinterpreted radar data and badly overestimated the distance between the two ships. The poor design of the radar settings, coupled with unlighted range settings and a darkened bridge, make this scenario likely. Some critics have suggested that a simple and available technology, a small light bulb on the radar set aboard the ''Stockholm'', might have averted the entire disaster. Instead, it is likely that he unintentionally steered the Swedish ship into what became a collision with the Italian liner. |

|||

* Studies of the actions of each ship confirm another factor which was long suspected, that once sight contact was established, each ship took evasive actions which only worsened the situation. |

|||

* Exploration of ''Andrea Doria'''s impact area revealed that ''Stockholm''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> bow had ripped a much larger gash in the critical area of the large fuel tanks and watertight compartments of the Italian liner than had been thought in 1956. The question of the "missing" watertight door, although still unanswered, was probably moot: ''Andrea Doria'' was doomed immediately after the collision. |

|||

== Diving on the wreck site == |

|||

[[Image:ADmarschall.jpg|thumb|300px|A painting of the decaying ''SS Andrea Doria'' circa 2005, with its superstructure gone and hull broken after 50 years of submersion in swift North Atlantic currents.]] |

|||

Due to the luxurious appointments and relatively good condition of the wreck, with the top of the wreck lying initially in only 160 feet (50 m) of water, ''Andrea Doria'' is a frequent target of treasure divers and is commonly referred to as the "[[Mount Everest]] of [[scuba diving]]." The comparison to Mt. Everest originated, after a July 1983 dive on the Doria, by Capt. Alvin Golden, during a CBS News televised interview of the divers, following their return from a dive expedition, to the wreck, aboard the R/V Wahoo. The wreck is located at {{coord|40|29|30|N|69|51|00|W}}.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> |

|||

The day after ''Andrea Doria'' sank, divers [[Peter Gimbel]] and [[Joseph Fox]] managed to locate the wreck of the ship, and published pictures of the wreck in [[Time (magazine)|''TIME'' magazine]]. Gimbel later conducted a number of salvage operations on the ship, including salvaging the First Class Bank Safe in 1981. Despite speculation that passengers had deposited many valuables, the safe, opened on live television in 1984, yielded little other than American silver certificates and Italian bank notes. This disappointing outcome apparently confirmed other speculation that most ''Andrea Doria'' passengers, in anticipation of the ship's scheduled arrival in New York City the following morning, had already retrieved their valuables prior to the collision. |

|||

The ship's bell, often considered the 'prize' of a wreck, was retrieved in the late 1980s by a team of divers led by Bill Nagle.<ref>[[Robert Kurson|Kurson, Robert]]: "[[Shadow Divers]]", Alfred A. Knopf Publishing, 2004</ref> The statue of Genoese Admiral [[Andrea Doria]], for whom the ship was named, was removed from the first-class lounge, being cut off at the ankles to accomplish this. Examples of the ship's china have long been considered valuable mementos of diving the wreck. However, after years of removal of artifacts by divers, little of value is thought to remain. |

|||

As of 2007, years of ocean submersion have taken their toll. The wreck has aged and deteriorated extensively, with the hull now fractured and collapsed. The upper decks have slowly slid off the wreck to the seabed below. As a result of this transformation, a large debris field flows out from the hull of the liner. Once-popular access points frequented by divers, such as Gimbel's Hole, no longer exist. Divers call the ''Andrea Doria'' a "noisy" wreck as it emits various noises due to continual deterioration and the currents' moving broken metal around inside the hull. However, due to this decay new access areas are constantly opening up for future divers on the ever-changing wreck. |

|||

===Deaths=== |

|||

Artifact recovery on the ''Andrea Doria'' has not been without additional loss of life. Fifteen scuba divers have lost their lives diving the wreck,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.njscuba.net/sites/site_andrea_doria.html|accessmonthday=July 10 | |

|||

accessyear=2006|title=New Jersey Scuba Diver - Dive Sites - Andrea Doria}}</ref> and diving conditions at the wreck site are considered very treacherous. Strong currents and heavy sediment that can reduce visibility to zero pose as serious hazards to diving this site. Dr. [[Robert Ballard]], who visited the site in a [[U.S. Navy]] submersible in 1995, reported that thick fishing nets draped the hull. An invisible web of thin fishing lines, which can easily snag scuba gear, provides more danger. Furthermore, the wreck is slowly collapsing; the top of the wreck is now at 240 feet (80 m), and many of the passageways have begun to collapse. |

|||

* 1985 — John Ormsby died after being caught in wires and drowning.<ref name="sicolamurley"/> |

|||

* 1998 — Craig Sicola, Richard Roost and Vincent Napoliello all died diving on the ''Andrea Doria''.<ref name="sicolamurley">{{cite web|accessmonthday=July 10 |accessyear=2006|url=http://www.capecodonline.com/special/andreadoria/andreadoria22.htm|title= Divers risk all for a date with Andrea Doria }}</ref> |

|||

* 1999 — Christopher Murley and Charles J. McGurr both died of apparent heart attacks preparing to dive.<ref name="sicolamurley"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B03E7D81531F933A05754C0A96F958260|accessmonthday=July 10 |accessyear=2006|title=National News Briefs; Man Dies After Dive To Andrea Doria Wreck - New York Times}}</ref> |

|||

* 2002 — William Schmoldt died from [[decompression sickness]].<ref>{{cite web|accessmonthday=July 10 |accessyear=2006|url=http://www.projo.com/news/content/projo_20020806_newdive6.1dbef.html|title= |

|||

Diver exploring wreck off Mass. stricken, dies}}</ref> |

|||

* 2006 — Researcher [[David Bright]] died from decompression sickness.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20060711/ap_on_re_us/obit_bright|accessmonthday=July 10 | |

|||

accessyear=2006|title=Researcher died after Andrea Doria dive - Yahoo! News}}</ref> |

|||

*2008 — Terry DeWolf of Houston, Texas died during dive on wreck, cause of death is still undetermined. This death raises the total to 15.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www1.whdh.com/news/articles/local/BO83773/|accessmonthday=July 31 | |

|||

accessyear=2008|title=Diver died exploring famed shipwreck off Nantucket}}</ref> |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||

[[Image:WreathInTheWater.jpg|275px|right|thumb|Memorial wreath placed at ''Andrea Doria'' shipwreck site by survivors, July 2002.]] |

|||

''Stockholm''<nowiki>'s</nowiki> bow was repaired at a cost of $1 million. Today, it sails as the ''Athena'' and is registered in Portugal. |

|||

Several books have been written about the ''Andrea Doria''. The most recent, ''Alive on the Andrea Doria: The Greatest Sea Rescue in History'', is by survivor Pierette Domenica Simpson. Published in 2006, in both the U.S. and in Italy (L'Ultima Notte dell'Andrea Doria), it gives eyewitness accounts and scientific explanations.[http://www.pierettesimpson.com][http://andreadoriabook.com] The story of the accident was retold by [[Alvin Moscow]] in his book ''Collision Course: The Story of the Collision Between the 'Andrea Doria' and the 'Stockholm''', which was published in 1959. Author [[William Hoffer]]'s ''Saved: the Story of the Andrea Doria-The Greatest Sea Rescue in History'' was published in 1979, and in 2003 Richard Goldstein wrote ''Desperate Hours: The Epic Rescue Of The Andrea Doria''. 2004's ''[[Shadow Divers]],'' by [[Robert Kurson]], provides accounts of wreckage divers at the site as a precursor to the book's main story. Each of the books presented information not in the others, providing varying perspectives. Boston newspaper photographer [[Harry Trask]], who arrived at the scene in a small airplane after many media people had left, took a series of photographs of the ''Andrea Doria's'' final moments above water which won a [[Pulitzer Prize]]. Several documentaries have been produced: National Geographic, PBS Secrets of the Dead, Discovery, History and others. |

|||

Two bronze medallions, commissioned by survivors, Pierette Domenica Simpson and Jerome Reinert, and a survivor's daughter Angela Addario, are in the South Street Seaport Museum of New York, and in the Museo del Mare of Genova, Italy. California sculptor, Daniel Oberti, created the two works called ''The Greatest Sea Rescue in History''.[http://danieloberti.com] |

|||

Survivors went on with their lives with a wide range of experiences. Captain Calamai never accepted another command, and lived the rest of his life in sadness "as a man who has lost a son" according to his daughter. Most of the other officers returned to the sea. Some survivors had mental problems for years after the incident, while others felt their experience had helped them value their lives more preciously. A group of survivors remains in contact with each other through a [http://www.andreadoria.org web site run by the family of Anthony Grillo], an ''Andrea Doria'' survivor. Some stay in touch through a newsletter, and there have been reunions and memorial services. |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

===Print=== |

|||

*Alive on the Andrea Doria! The Greatest Sea Rescue in History, Pierette Domenica Simpson, 2006, Purple Mountain Press, Fleischmans, New York |

|||

*{{cite book | author= Ballard, Robert D. | title=Lost Liners: From the Titanic to the Andrea Doria the Ocean Floor Reveals Its Greatest Ships | year=1997 | publisher=Hyperion | id=ISBN 0-7868-6296-3}} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Carletti, Stefano | title=Andrea Doria '74 | year=1968 | publisher=Gherando Casini Ed, Italy | ISBN= }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Gentile, Gary | title=Andrea Doria: Dive to an Era | year=1989 | publisher=Gary Gentile Productions | id=ISBN 0-9621453-0-0 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Gladstone, Eugene W. | title=In The Wake Of The Andrea Doria: A Candid Autobiography by Eugene W. Gladstone | year=1966 | publisher=McClelland and Stewart Limited, Canada | id= }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Goldstein, Richard | title=Desperate Hours: The Epic Rescue Of The Andrea Doria | year=2003 | publisher=John Wiley & Sons | id=ISBN 0-471-42352-1 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Haberstroh, Joe | title=Fatal Depth: Deep Sea Diving, China Fever and the Wreck of the Andrea Doria | year=2003 | publisher=The Lyons Press | id=ISBN 1-58574-457-3 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Hoffer, William | title=Saved: the Story of the Andrea Doria-The Greatest Sea Rescue in History | year=1982 | publisher=Simon & Schuster | id=ISBN 0-517-36490-5 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Kurson, Robert | title=Shadow Divers: The True Adventure of Two Americans Who Risked Everything to Solve One of the Last Mysteries of World War II | year=2004 | publisher=Random House | id=ISBN 0-375-50858-9 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Kohler, Peter C. | title=The Lido Fleet | year=1988 | publisher=Seadragon Press | id=ISBN 0-9663052-0-5 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Mattsson, Algot (Translated from Swedish by Professor E. Fisher and edited by Gordon W. Paulsen) | title=Out Of The Fog: The Sinking Of The Andrea Doria | year=1986 | publisher=Cornell Maritime Press | id=ISBN 0-87033-545-6 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=McMurray, Kevin F. | title=Deep Descent: Adventure And Death Diving The Andrea Doria | year=2001 | publisher=Pocket Books | id=ISBN 0-7434-0062-3 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Meurn, Robert J. | title=Watchstanding Guide for the Merchant Officer | year=1990 | publisher=Cornell Maritime Press | id=ISBN 0-87033-409-3 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Moscow, Alvin | title=Collision Course | year=1959 | publisher=Putnam Publishing Group | id=ISBN 0-448-12019-4 }} ''Noted updated version published in 1981''. |

|||

*[[New York Times]], ''Doria Skin Diver Dies, Was In Group Set to Film Ship-Oxygen Supply Cut Off'', August 2, 1956, Page 13. |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

===Online and film=== |

|||

*Binfield, Kevin. ''Writings of the Luddites'', (2004), Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-7612-5 |

|||

*[http://www.pierettesimpson.com Alive on the Andrea Doria! The Greatest Sea Rescue in History] and [http://www.andreadoriabook.com] |

|||

*Fox, Nicols. ''Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite History in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives'', (2003), Island Press] ISBN 1-55963-860-5 |

|||

*[http://www.andreadoria.org Andrea Doria - Tragedy and Rescue at Sea ([[July 23]], 2005)]. ''AndreaDoria.org''. |

|||

*Jones, Steven E. ''Against Technology: From Luddites to Neo-Luddism'', (2006) Routledge, ISBN 9780415978682 |

|||

*[http://www.garemaritime.com/features/andrea-doria/ Andrea Doria - The Sinking of the Unsinkable] ''Gare Maritime'' |

|||

*[[Kirkpatrick Sale|Sale, Kirkpatrick]]. ''Rebels Against the Future: The Luddites and Their War on the Industrial Revolution'', (1996) ISBN 0-201-40718-3 |

|||

*Othfors, Daniel. Andrea Doria. ''[http://www.greatoceanliners.net/ The Great Ocean Liners]''. |

|||

*[http://www.lostliners.com/Liners/Italia/Andrea_Doria/ship.html Andrea Doria: The Grand Dame of the Sea (2000)]. ''LostLiners.com'' |

|||

*[http://www.pbs.org/lostliners/andrea.html#top Andrea Doria]. ''Lost Liners: PBS Online''. |

|||

*[http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/case_andreadoria/ Secrets of the Dead: The Sinking of the Andrea Doria] on ''PBS Online'' and also shown on The [[History Channel]] - see [http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0917964] |

|||

*In the closing frames of the film [[On the Waterfront]] (1954), the ''Andrea Doria'' can be seen underway in [[New York Harbour]] |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

<!--===========================({{NoMoreLinks}})=============================== |

|||

* [http://www.oceanliner.org/johnson.htm Story of a Stockholm Crewmember] |

|||

| PLEASE BE CAUTIOUS IN ADDING MORE LINKS TO THIS ARTICLE. WIKIPEDIA IS | |

|||

* [http://www.andreadoria.org/TheSouls/ Andrea Doria Crew and Passenger List] |

|||

| NOT A COLLECTION OF LINKS NOR SHOULD IT BE USED FOR ADVERTISING. | |

|||

* [http://www.carlonordling.se/doria/doria.html A reconstruction of the Andrea Doria/Stockholm collision] |

|||

| | |

|||

* [http://www.forgotten-ny.com/YOU'D%20NEVER%20BELIEVE/yellowsub/yellowsub.html Yellow Submarine: a failed attempt to raise Andrea Doria] |

|||

| Excessive or inappropriate links WILL BE DELETED. | |

|||

{{featured article}} |

|||

| See [[Wikipedia:External links]] and [[Wikipedia:Spam]] for details. | |

|||

| | |

|||

| If there are already plentiful links, please propose additions or | |

|||

| replacements on this article's discussion page. Or submit your link | |

|||

| to the appropriate category at the Open Directory Project (www.dmoz.org)| |

|||

| and link back to that category using the {{dmoz}} template. | |

|||

===========================({{NoMoreLinks}})===============================--> |

|||

{{wikt|Luddite}} |

|||

*[http://www.sniggle.net/ludd.php On-line Luddism Index] |

|||

*[http://www.themodernword.com/pynchon/pynchon_essays_luddite.html ''Is it O.K. to be a Luddite?'' by Thomas Pynchon] |

|||

*[http://carbon.cudenver.edu/~mryder/itc_data/luddite.html ''Luddism and the Neo-Luddite Reaction'' by Martin Ryder, University of Colorado at Denver School of Education] |

|||

*[http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/calendar/2004/02_february.html CBC program Ideas on Luddites] |

|||

*[http://campus.murraystate.edu/academic/faculty/kevin.binfield/luddites/LudditeHistory.htm Extracts] from Kevin Binfield's book. |

|||

*[http://recollectionbooks.com/siml/library/index.html#Luddites Luddites] Stan Iverson Memorial Archives (articles, links & timeline) |

|||

*[http://www.marxists.org/history/england/combination-laws/index.htm Historical reports and accounts on key events concerning the Luddite movement hosted by Marxists.org] |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:History of social movements]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Technology in society]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Industrial Revolution]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:19th century in the United Kingdom]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Eponyms]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Pejorative terms for people]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:History of the textile industry]] |

||

[[ar:لاضية]] |

|||

{{Link FA|he}} |

|||

[[ |

[[ca:Ludisme]] |

||

[[ |

[[de:Luddismus]] |

||

[[es:Ludismo]] |

|||

[[fr:Andrea Doria (paquebot)]] |

|||

[[eo:Luddismo]] |

|||

[[it:Andrea Doria (transatlantico)]] |

|||

[[fr:Luddisme]] |

|||

[[he:אנדריאה דוריה (ספינה)]] |

|||

[[ |

[[it:Luddismo]] |

||

[[ |

[[he:לודיטים]] |

||

[[ |

[[nl:Luddisme]] |

||

[[ja:ラッダイト運動]] |

|||

[[sv:S/S Andrea Doria]] |

|||

[[no:Ludditter]] |

|||

[[pl:Luddyzm]] |

|||

[[pt:Luddismo]] |

|||

[[ru:Луддит]] |

|||

[[sr:Лудити]] |

|||

[[fi:Luddiitit]] |

|||

[[sv:Ludditer]] |

|||

[[zh:卢德运动]] |

|||

Revision as of 22:03, 12 October 2008

The Luddites were a social movement of British textile artisans in the early nineteenth century who protested—often by destroying mechanized looms—against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution, which they felt threatened their livelihood.

This English historical movement has to be seen in its context of the harsh economic climate due to the Napoleonic Wars, and the degrading working conditions in the new textile factories; but since then, the term Luddite has been used derisively to describe anyone opposed to technological progress and technological change.

The Luddite movement, which began in 1811, took its name from the fictive Ned Ludd. For a short time the movement was so strong that it clashed in battles with the British Army. Measures taken by the government included a mass trial at York in 1812 that resulted in many executions and penal transportation.

The principal objection of the Luddites was the introduction of new wide-framed automated looms that could be operated by cheap, relatively unskilled labour, resulting in the loss of jobs for many skilled textile workers.

History

The original Luddites claimed to be led by one "King Ludd" (also known as "General Ludd" or "Captain Ludd") whose signature appears on a "workers' manifesto" of the time. King Ludd was based on the earlier Ned Ludd, who some believed to have destroyed two large stocking frames in the village of Anstey, Leicestershire in 1779. Naturally, in a situation where machine breaking could lead to heavy penalties or even execution, the use of an imaginary name was an understandable tactical necessity.

Research by historian Kevin Binfield[1] is particularly useful in placing the Luddite movement in historical context—as organised action by stockingers had occurred at various times since 1675, and the present action had to be seen in the context of the hardships suffered by the working class during the Napoleonic Wars.

The movement began in Nottingham in 1811 and spread rapidly throughout England in 1811 and 1812. Many wool and cotton mills were destroyed until the British government harshly suppressed the movement. The Luddites met at night on the moors surrounding the industrial towns, practising drills and manoeuvres and often enjoyed local support. The main areas of the disturbances were Nottinghamshire in November 1811, followed by the West Riding of Yorkshire in early 1812 and Lancashire from March 1813. Battles between Luddites and the military occurred at Burton's Mill in Middleton, and at Westhoughton Mill, both in Lancashire. It was rumoured at the time that agents provocateurs employed by the magistrates were involved in provoking the attacks.[citation needed] Magistrates and food merchants were also objects of death threats and attacks by the anonymous King Ludd and his supporters. Some industrialists even had secret chambers constructed in their buildings, which may have been used as a hiding place.[2]

"Machine breaking" (industrial sabotage) was subsequently made a capital crime by the Frame Breaking Act (Lord Byron, one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites, famously spoke out against this legislation), and 17 men were executed after an 1813 trial in York. Many others were transported as prisoners to Australia. At one time, there were more British troops fighting the Luddites than Napoleon I on the Iberian Peninsula.[citation needed] Three Luddites ambushed and murdered a mill-owner (William Horsfall from Ottiwells Mill in Marsden) at Crosland Moor, Huddersfield; the Luddites responsible were hanged in York, and shortly thereafter 'Luddism' waned.

However, the movement can also be seen as part of a rising tide of English working-class discontent in the early 19th century (see also, for example, the Pentrich Rising of 1817, which was a general uprising, but led by an unemployed Nottingham stockinger, and probable ex-Luddite, Jeremiah Brandreth). An agricultural variant of Luddism, centering on the breaking of threshing machines, was crucial to the widespread Swing Riots of 1830 in southern and eastern England.

In recent years, the terms Luddism and Luddite or Neo-Luddism and Neo-Luddite have become synonymous with anyone who opposes the advance of technology due to the cultural and socioeconomic changes that are associated with it.

Criticism of Luddism

The term "Luddite fallacy" has become a concept in neoclassical economics reflecting the belief that labour-saving technologies (i.e., technologies that increase output-per-worker) increase unemployment by reducing demand for labour. The "fallacy" lies in assuming that employers will seek to keep production constant by employing a smaller, more productive workforce instead of allowing production to grow while keeping workforce size constant.[3]

E. P. Thompson's view of Luddism

In his work on English history, The Making of the English Working Class, E. P. Thompson presented an alternative view of Luddite history. He argues that Luddites were not opposed to new technology in itself, but rather to the abolition of set prices and therefore also to the introduction of the free market.

Thompson argues that it was the newly-introduced economic system that the Luddites were protesting. For example, the Luddite song, "General Ludd's Triumph":

- The guilty may fear, but no vengeance he aims

- At the honest man's life or Estate

- His wrath is entirely confined to wide frames

- And to those that old prices abate

"Wide frames" were the cropping frames, and the old prices were those prices agreed by custom and practice. Thompson cites the many historical accounts of Luddite raids on workshops where some frames were smashed whilst others (whose owners were obeying the old economic practice and not trying to cut prices) were left untouched. This would clearly distinguish the Luddites from someone who was today called a luddite; whereas today a luddite would reject new technology because it is new, the Luddites were acting from a sense of self-preservation rather than merely fear of change.

The Luddites in fiction

- Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, a social novel set against the backdrop of the Luddite riots in the Yorkshire textile industry in 1811–1812.

- The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, a novel speculating on what might have been had Charles Babbage completed his Difference Engine during the Industrial Revolution.

- Mark of the Rani, a story from the 1985 season of the British TV program Doctor Who is set during the height of the Luddite movement.

External links

- Luddites and Luddism (Kevin Binfield, ed.)

References

- ^ Binfield, Kevin. Luddites and Luddism: History, Texts Interpretation. http://campus.murraystate.edu/academic/faculty/kevin.binfield/luddites/LudditeHistory.htm Accessed 4 June 2008.

- ^ BBC NEWS | England | Leicestershire |Workmen discover secret chambers

- ^ Easterly, William (2001). The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-262-55042-3.

See also

- Antimodernism

- Critique of technology

- Jacquard loom

- Neo-Luddism

- Peterloo

- Propaganda of the deed

- Sabotage

- Swing Riots

- Technophobia

- Technorealism

- Techno-utopianism

Bibliography

- Binfield, Kevin. Writings of the Luddites, (2004), Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-7612-5

- Fox, Nicols. Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite History in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives, (2003), Island Press] ISBN 1-55963-860-5

- Jones, Steven E. Against Technology: From Luddites to Neo-Luddism, (2006) Routledge, ISBN 9780415978682

- Sale, Kirkpatrick. Rebels Against the Future: The Luddites and Their War on the Industrial Revolution, (1996) ISBN 0-201-40718-3

External links

- On-line Luddism Index

- Is it O.K. to be a Luddite? by Thomas Pynchon

- Luddism and the Neo-Luddite Reaction by Martin Ryder, University of Colorado at Denver School of Education

- CBC program Ideas on Luddites

- Extracts from Kevin Binfield's book.

- Luddites Stan Iverson Memorial Archives (articles, links & timeline)

- Historical reports and accounts on key events concerning the Luddite movement hosted by Marxists.org