Kidnapping and murder of Kenneth Bigley: Difference between revisions

→Second and third videos: expanding ref coverage |

No edit summary |

||

| (164 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|British civil engineer and murder victim}} |

|||

{{No footnotes|date=March 2010}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=August 2014}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2014}} |

|||

{{Infobox person |

|||

| name = Kenneth Bigley |

|||

| image = Bigleyandwife.jpg |

|||

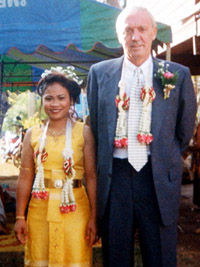

| caption = Bigley (right) with his wife Sombat in 1998 |

|||

| birth_name = Kenneth John Bigley |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1942|4|22|df=yes}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Liverpool]], [[England]], UK |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|2004|10|7|1942|4|22|df=yes}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Baghdad]], Iraq |

|||

| death_cause = [[Decapitation]] |

|||

| nationality = [[British people|British]] |

|||

| occupation = |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Kenneth John Bigley''' (22 April 1942 – 7 October 2004) was a British civil engineer who was [[Kidnapping|kidnapped]] by [[Islamic extremism|Islamic extremists]] in the [[Mansour district|al-Mansour district]] of [[Baghdad]], [[Iraq]], on 16 September 2004, along with his colleagues, U.S. citizens [[Jack Hensley]] and [[Eugene Armstrong]]. Following the murders of Hensley and Armstrong by [[beheading]] over the course of three days, Bigley was killed in the same manner two weeks later, despite the attempted intervention of the [[Muslim Council of Britain]] and the indirect intervention of the British government. Videos of the killings were posted on websites and blogs.<ref name="timeline">{{cite web |date=8 October 2004 |title=Timeline: Ken Bigley |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3726846.stm |access-date=9 January 2012 |website=[[BBC News]]}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Bigleyandwife.jpg|right|frame|Kenneth Bigley and his wife Sombat at their wedding in 1998.]] |

|||

'''Kenneth John Bigley''' (22 April 1942 - 7 October 2004), born [[Liverpool]], [[England]], was a [[civil engineer]] who was [[Kidnapping|kidnapped]] in the [[Mansour district|al-Mansour district]] of Baghdad, Iraq on 16 September 2004, along with his colleagues [[Jack Hensley]] and [[Eugene Armstrong]], both [[United States|U.S.]] citizens.<ref name="timeline">http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3726846.stm</ref> The three men were working for Gulf Supplies and Commercial Services, a Kuwaiti company working on reconstruction projects in Iraq. They knew their house was being watched and that they were in grave danger because their Iraqi house guard told them he was quitting because he had been threatened by militias that knew he was protecting Americans and British workers, but Bigley and the two Americans decided it was worth it to live with the danger. All were subsequently [[Decapitation|beheaded]]. |

|||

== Capture == |

|||

On 18 September, the [[Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad|Tawhid and Jihad]] ("Oneness of God and [[Jihad]]") [[Islamic extremist]] group, led by [[Jordan]]ian [[Abu Musab al-Zarqawi]], released a video of the three men kneeling in front of a Tawhid and Jihad banner. The kidnappers said they would kill the men within 48 hours if their demands for the release of Iraqi women prisoners held by [[Coalition of the willing|coalition forces]] were not met. |

|||

The three men were working for [http://Gulf%20Supplies%20and%20Commercial%20Service Gulf Supplies and Commercial Service]s, a Kuwaiti company working on reconstruction projects in Iraq. The men knew their home was being watched and realised they were in great danger when their Iraqi house guard informed them he was leaving due to threats by militias for protecting American and British workers. |

|||

Bigley and the two Americans decided it was worth the risk and continued to live in the house until their abduction on 16 September. |

|||

On 18 September, the [[Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad|Tawhid and Jihad]] ("Oneness of God and [[Jihad]]") Islamic extremist group, led by Jordanian [[Abu Musab al-Zarqawi]], released a video of the three men kneeling in front of a Tawhid and Jihad banner. The kidnappers said they would kill the men within 48 hours if their demands for the release of Iraqi women prisoners held by [[Coalition of the willing (Iraq war)|coalition forces]] were not met. Armstrong was killed on 20 September when the deadline expired, Hensley 24 hours later.<ref name="timeline" /> |

|||

Armstrong was beheaded on 20 September when the deadline expired,<ref name="timeline" /> Hensley 24 hours later,<ref name="timeline" /> and Bigley over two weeks later, despite the intervention of the [[Muslim Council of Britain]] and the indirect intervention of the British government. Videos of the killings were posted on websites and blogs. Using voice-recognition technology, the [[Central Intelligence Agency]] (CIA) has claimed that al-Zarqawi personally carried out the beheading of Armstrong. |

|||

==Negotiations for release== |

|||

__TOC__ |

|||

After Armstrong and Hensley were killed, the British government and media responded by turning Bigley's fate into Britain's major political issue during this period, leading to subsequent claims that the government had become a hostage to the situation. The [[Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs|British Foreign Secretary]] [[Jack Straw]] and the Prime Minister [[Tony Blair]] personally contacted the Bigley family several times to assure them that everything possible was being done, short of direct negotiation with the kidnappers. It was also reported that a [[Special Air Service]] (SAS) team had been placed on standby in Iraq in the event that a rescue mission might become possible.{{citation needed|date=February 2018}} |

|||

The British government issued a statement saying it held no Iraqi women prisoners, and that the only two women known to be in US custody were two so-called high-profile Iraqi scientists, British-educated [[Rihab Taha]] and US-educated [[Huda Salih Mahdi Ammash]]. Both women participated in Iraq's biological-weapons programme, according to the United Nations weapons inspectorate. News reports had earlier suggested that other Iraqi women were indeed being held in US custody, but it is not known to what extent these reports were out-of-date by the time of Bigley's kidnap.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/women/story/0,3604,1220673,00.html|location=London|work=[[The Guardian]]|first=Luke|last=Harding|title=The other prisoners|date=20 May 2004}}</ref> The Iraqi provisional government stated that Taha and Ammash could be released immediately, stressing that this was about to happen anyway, as no charges had been brought against the women.{{citation needed|date=February 2018}} |

|||

== Capture and negotiations for release == |

|||

After Armstrong and Hensley were killed, the British government and media responded by turning Bigley's fate into Britain's major political issue during this period, leading to subsequent claims that the government had become a hostage to the situation, as [[President of the United States|President]] [[Jimmy Carter]] had arguably done during the 444-day [[Iran hostage crisis]] in 1979-81. |

|||

===Second and third videos=== |

|||

[[Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs|British Foreign Secretary]] [[Jack Straw]] and [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|Prime Minister]] [[Tony Blair]] personally contacted the Bigley family several times to assure them that everything possible was being done, short of direct negotiation with the kidnappers. It was also reported that a [[Special Air Service]] (SAS) team had been placed on standby in Iraq in the event that a rescue mission might become possible. |

|||

A second [[beheading video]] was released on 22 September by Bigley's captors, this time showing Bigley pleading for his life and begging the British Prime Minister Tony Blair to save him. Clearly exhausted and highly emotional, Bigley spoke directly to Blair: "I need you to help me now, Blair, because you are the only person on God's earth who can help me."<ref name="timeline"/> The video was posted on several websites, blogs and shown on [[Al Jazeera Media Network|Al Jazeera]] television. |

|||

Around this time it emerged that Bigley's mother Lil (then 86 years old) had been born in [[Dublin]] and was therefore entitled to be a citizen of the [[Republic of Ireland]]; this meant Bigley himself was also an Irish citizen from birth. It was hoped this status would aid his release, as Ireland did not participate in the [[2003 invasion of Iraq]], and the Irish Government issued Bigley an Irish passport ''[[wikt:in absentia|in absentia]]'',<ref name="timeline"/> which was shown on Al Jazeera television. The [[Labour Party (Ireland)|Irish Labour Party]] spokesman on foreign affairs, [[Michael D. Higgins]], made an appeal on al-Jazeera. [[Sinn Féin]] leader [[Gerry Adams]] made two appeals, one on 30 September and a second on 7 October.<ref name="timeline"/> |

|||

The British government issued a statement saying it held no Iraqi women prisoners, and that the only two women known to be in U.S. custody were two so-called high-profile Iraqi scientists, British-educated Dr. [[Rihab Taha]] and U.S.-educated Dr. [[Huda Salih Mahdi Ammash]]. Both women participated in Iraq's biological-weapons program, according to the [[United Nations]] weapons inspectorate. |

|||

News reports had earlier suggested that other Iraqi women were indeed being held in U.S. custody, but it is not known to what extent these reports were out-of-date by the time of Bigley's kidnap.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/women/story/0,3604,1220673,00.html | location=London | work=The Guardian | first=Luke | last=Harding | title=The other prisoners | date=20 May 2004}}</ref> |

|||

On 24 September, 50,000 leaflets prepared by the [[Foreign and Commonwealth Office|British Foreign Office]], asking for information about Bigley's whereabouts, were distributed in al-Mansour, the wealthy district of Baghdad Bigley had been living in. In his home town of [[Liverpool]], Christian and Muslim religious and civic leaders held joint prayer sessions for his safe return. The [[Muslim Council of Britain]] condemned the kidnapping, saying it was contrary to the teachings of the [[Qur'an]] and sent a senior two-man delegation to Iraq on 26 September to negotiate on Bigley's behalf.<ref name="timeline"/> |

|||

The Iraqi provisional government stated that Dr. Taha and Dr. Ammash could be released immediately, stressing that this was about to happen anyway, as no charges had been brought against the women. |

|||

Bigley's family, particularly his brother Paul, was successful, with the help of the Irish government, in eliciting support for Bigley's release from Palestinian leader [[Yasser Arafat]], [[Abdullah II of Jordan|King Abdullah of Jordan]], and [[Muammar Gaddafi|Colonel Gaddafi of Libya]], who made public statements. A third video was released on 29 September, showing Bigley chained inside a small chicken-wire cage, wearing an orange boiler suit apparently intended to be reminiscent of those worn by inmates at the US detainment facility at [[Guantanamo Bay detainment camp|Guantanamo Bay]], Cuba. In the video, Bigley again begged for his life, saying, "Tony Blair is lying. He doesn't care about me. I'm just one person." On 1 October, another 100,000 leaflets asking for information about Bigley were distributed by the British consulate in Baghdad.<ref name="timeline"/> |

|||

=== Second and third videos === |

|||

A second video was released on 22 September by Bigley's captors, this time showing Bigley pleading for his life and begging British Prime Minister Tony Blair to save him. Clearly exhausted and highly emotional, Bigley spoke directly to Blair: "I need you to help me now, [Mr.] Blair, because you are the only person on God's earth who can help me." <ref name="timeline" /> The video was posted on several websites, blogs and shown on [[al Jazeera]] television. |

|||

==Death== |

|||

Around this time it emerged that Bigley's mother, Lil, 86 years old at the time of his abduction, had been born in [[Dublin]] and was therefore an Irish citizen; this meant Bigley himself was also an Irish citizen from birth. It was hoped this status would aid his release, as Ireland did not participate in the [[2003 invasion of Iraq]], and the Irish Government issued Bigley an Irish passport ''[[in absentia]]'', which was shown on al-Jazeera television. Irish Labour Party spokesman on foreign affairs Michael D. Higgins made an appeal on al-Jazeera. [[Sinn Féin]] leader [[Gerry Adams]] made two appeals, one on 30 September and a second on 7 October.<ref name="timeline" /> |

|||

Despite the efforts to save him, Bigley was [[Decapitation|beheaded]] on 7 October 2004. His death was first reported on [[Abu Dhabi]] television the following day.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/08/international/middleeast/british-hostage-is-beheaded-in-iraq.html|title=British Hostage Is Beheaded in Iraq|first=Edward|last=Wong|date=8 October 2004|work=[[New York Times]]}}</ref> A multi-faith [[funeral|memorial service]], attended by Tony Blair and his wife [[Cherie Blair|Cherie]], was held for him in Liverpool on 13 November 2004. His body has not been recovered, although an alleged al-Qaeda terrorist awaiting trial for the [[2003 Istanbul bombings]] has claimed he is "buried in a ditch at the entrance to [[Fallujah]]".<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/4933490.stm | website=[[BBC News]]|title=Bigley body claims investigated|date=22 April 2006}}</ref> |

|||

The kidnappers made a film apparently showing Bigley's murder, and the tape was subsequently posted on Islamist websites and on one [[shock site]]. According to reporters who watched the film, Bigley was wearing an orange jumpsuit, and read out a statement, before one of the kidnappers stepped forward and cut off his head with a knife. The bloodied head was then placed on top of Bigley's abdomen. News reports published after Bigley's death suggested he had briefly managed to escape from the kidnappers with the help of two [[MI6]] agents of Syrian and Iraqi origin, who paid two of his captors to help him.<ref name="The Times">{{cite news|url=http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/uk_news/article241664.ece|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140225001730/http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/uk_news/article241664.ece|url-status=dead|archive-date=25 February 2014|location=London|work=[[The Times]]|first1=Hala|last1=Jaber|title=Bigley beheaded after MI6 rescue backfired|date=10 October 2004}} (subscription required for full article)</ref> The captors attempted to drive Bigley, who was carrying a gun and was disguised, out of town, the reports said, but he was spotted and recaptured at an insurgent checkpoint. The two captors were purportedly executed shortly thereafter.<ref name="The Times"/> |

|||

On 24 September, 50,000 leaflets prepared by the [[Foreign and Commonwealth Office|British Foreign Office]], asking for information about Bigley's whereabouts, were distributed in al-Mansour, the wealthy district of Baghdad Bigley had been living in.<ref name="timeline" /> In his home city of Liverpool, Christian and Muslim religious and civic leaders held joint prayer sessions for his safe return.<ref name="timeline" /> |

|||

==Torture-chamber discovery== |

|||

The [[Muslim Council of Britain]] condemned the kidnapping, saying it was contrary to the teachings of the [[Qur'an]] and sent a senior two-man delegation to Iraq on September 26 to negotiate on Bigley's behalf.<ref name="timeline" /> Bigley's family, particularly his brother Paul, was successful, with the help of the Irish government, in eliciting support for Bigley's release from Palestinian leader [[Yasser Arafat]], [[Abdullah II of Jordan|King Abdullah of Jordan]], and [[Muammar al-Gaddafi|Colonel Gadaffi of Libya]], who made public statements. |

|||

The chicken-wire cage in which Bigley was filmed was found in November 2004 by US troops in a house in Fallujah during the [[Second Battle of Fallujah]]. The US military stated that, in 20 houses, it found [[paraphernalia]] associated with hostage-holding and [[torture]], including shackles, blood-stained walls, and a torture chamber.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1539706/Man-questioned-over-Ken-Bigley-murder.html|location=London|work=[[The Daily Telegraph|The Telegraph]]|title=Man questioned over Ken Bigley murder|author=Henry, Emma|date=17 January 2007}}</ref> |

|||

==''The Spectator'' controversy== |

|||

A third video was released on 29 September<ref name="timeline" /> showing Bigley chained inside a small chicken-wire cage, wearing an orange boiler suit apparently intended to be reminiscent of those worn by inmates at the U.S. facility in [[Guantanamo Bay detainment camp|Guantanamo Bay]]. In the video, Bigley again begged for his life, saying, "Tony Blair is lying. He doesn't care about me. I'm just one person." |

|||

[[Boris Johnson]], the then editor of ''[[The Spectator]]'', was criticised for an editorial, written by [[Simon Heffer]], which appeared in the magazine on 16 October 2004 following the death of Bigley in Iraq, in which it was claimed that the response to Bigley's killing was fuelled by the fact he was from Liverpool, and went on to criticize the "drunken" fans at Hillsborough and call on them to accept responsibility for their "role" in the [[Hillsborough disaster|Hillsborough stadium disaster]] in 1989: |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

On 1 October, another 100,000 leaflets asking for information about Bigley were distributed by the British Foreign Office in Baghdad.<ref name="timeline" /> |

|||

The extreme reaction to Mr Bigley's murder is fed by the fact that he was a Liverpudlian. Liverpool is a handsome city with a tribal sense of community. A combination of economic misfortune — its docks were, fundamentally, on the wrong side of England when Britain entered what is now the European Union — and an excessive predilection for welfarism have created a peculiar, and deeply unattractive, psyche among many Liverpudlians. They see themselves whenever possible as victims, and resent their victim status; yet at the same time they wallow in it. Part of this flawed psychological state is that they cannot accept that they might have made any contribution to their misfortunes, but seek rather to blame someone else for it, thereby deepening their sense of shared tribal grievance against the rest of society. The deaths of more than 50 Liverpool football supporters at Hillsborough in 1989 was undeniably a greater tragedy than the single death, however horrible, of Mr Bigley; but that is no excuse for Liverpool's failure to acknowledge, even to this day, the part played in the disaster by drunken fans at the back of the crowd who mindlessly tried to fight their way into the ground that Saturday afternoon. The police became a convenient scapegoat, and the ''Sun'' newspaper a whipping-boy for daring, albeit in a tasteless fashion, to hint at the wider causes of the incident.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.spectator.co.uk/2004/10/bigleys-fate/|title=Bigley's fate |work=[[The Spectator]]}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Johnson apologised at the time of the article, travelling to Liverpool to do so,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/hillsborough-boris-johnson-apologises-slurs-3334849|title=Hillsborough: Boris Johnson apologises for slurs in 2004 Spectator article (VIDEO)|first=Liverpool|last=Echo|date=13 September 2012|work=[[Liverpool Echo]]}}</ref> and again following the publication of the report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel in 2012; however, Johnson's apology was rejected by Margaret Aspinall, chairperson of the Hillsborough Families Support Group, whose son James, 18, died in the disaster: |

|||

== Death == |

|||

Despite the efforts to save him, Bigley was [[Decapitation|beheaded]] on 7 October 2004. His death was first reported on [[Abu Dhabi]] television the following day.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/08/international/middleeast/08CND-IRAQ.html "British Hostage Is Beheaded in Iraq"]</ref> A multi-faith [[funeral|memorial service]], attended by Tony Blair and his wife [[Cherie Blair|Cherie]], was held for him in Liverpool on 13 November. His body has not been recovered, although an alleged al-Qaeda militant awaiting trial for the [[2003 Istanbul bombings]] has claimed he is "buried in a ditch at the entrance to [[Fallujah]]".<ref>{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/4933490.stm | work=BBC News | title=Bigley body claims investigated | date=22 April 2006}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

The kidnappers made a film apparently showing Bigley's killing, and the tape was subsequently posted on Islamist websites and on one [[shock site|"shock" site]]. According to reporters who watched the film, Bigley was wearing an orange jumpsuit, and read out a statement, before one of the kidnappers stepped forward and cut off his head with a knife. |

|||

What he has got to understand is that we were speaking the truth for 23 years and apologies have only started to come today from them because of yesterday. It's too little, too late. It's fine to apologise afterwards. They just don't want their names in any more sleaze. No, his apology doesn't mean a thing to me.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-19589039|title=Mayor makes Hillsborough apology|date=13 September 2012|website=[[BBC News]]}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

News reports published after Bigley's death suggested he had briefly managed to escape from the kidnappers with the help of two [[MI6]] agents of [[Syria]]n and Iraqi origin, who paid two of his captors to help him.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2087-1302700,00.html | location=London | work=The Times | first1=Hala | last1=Jaber | title=Bigley beheaded after MI6 rescue backfired | date=10 October 2004}}</ref> The captors attempted to drive Bigley, who was carrying a gun and was disguised, out of town, the reports said, but he was spotted and recaptured at an insurgent checkpoint. The two captors were said to have been beheaded. |

|||

{{Portal|Biography|England}} |

|||

* [[Beheading video]] |

|||

After his death, the British [[mass media|media]] were criticised for the amount of [[news]] coverage his situation had been given. The same high-coverage news [[strategy]] was notably absent in the case of [[Margaret Hassan]], the Irish-born [[aid worker]], who held Irish, British and Iraqi citizenship, who was kidnapped on 19 October 2004 and killed two weeks later. |

|||

* [[Daniel Pearl]] |

|||

* [[Fabrizio Quattrocchi]] |

|||

Columnist and author [[Mark Steyn]] had his column pulled from the British ''[[Daily Telegraph]]'' on 11 October 2004 when in it he stated that Bigley's last words "Tony Blair has not done enough for me" would not be high up on his list of final utterances. |

|||

In October 2004, during an 18-night stint at London's [[Hammersmith Apollo]], the Scottish comedian and actor [[Billy Connolly]] was criticised for making jokes about the hostage Bigley.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/merseyside/3717462.stm BBC News: Connolly blasted over Bigley joke]</ref> Shortly after Connolly joked about the future killing of the hostage and touched on the subject of Bigley’s young Thai wife, Bigley was beheaded in Iraq. Connolly claims he was misquoted. He has declined to clarify what he actually said, claiming that the context was as important as the precise words used. However, it was reported that Connolly actually said "When you hear about Bigley in the news, don't you wish they would just get on with, it?" Connolly's routine has since been defended as an attack on the prurient media coverage of the incident, rather than a tasteless comment at the expense of the Bigleys.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-12775389|title=Why do people tell sick jokes about tragedies?|first=Jon|last=Kelly|work=BBC News website|date=18 March 2011}}</ref> |

|||

== Torture-chamber discovery == |

|||

The chicken-wire cage Bigley was filmed in was found in November 2004 by U.S. troops in a house in the Iraqi town of Fallujah during the [[Second Battle of Fallujah]].<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2004/11/22/uhouses.xml&sSheet=/portal/2004/11/22/ixportaltop.html | location=London | work=The Daily Telegraph}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/Iraq/Story/0,2763,1350982,00.html | location=London | work=The Guardian | title=The final battle | date=14 November 2004}}</ref> The U.S. military stated that, in 20 houses, it found [[paraphernalia]] associated with hostage-holding and [[torture]], including shackles, blood-stained walls, and a torture chamber. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{Portalbox|Biography|England|Terrorism}} |

|||

* [[2003 invasion of Iraq]] |

|||

* [[Human rights in post-invasion Iraq|Human rights situation in post-Saddam Iraq]] |

* [[Human rights in post-invasion Iraq|Human rights situation in post-Saddam Iraq]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Kim Sun-il]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[List of kidnappings]] |

||

* [[List of solved missing person cases]] |

|||

* [[Nick Berg]] |

* [[Nick Berg]] |

||

* [[Paul Marshall Johnson, Jr.]] |

* [[Paul Marshall Johnson, Jr.]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Piotr Stańczak]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Seif Adnan Kanaan]] |

||

* [[Jack Hensley]] |

|||

* [[Kim Sun-il]] |

|||

* [[Shosei Koda]] |

* [[Shosei Koda]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Steven Vincent]] |

||

* [[Seif Adnan Kanaan]] |

|||

* [[Piotr Stańczak]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 70: | Line 77: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3729158.stm Ken Bigley's wife mourns the loss of her husband] |

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3729158.stm Ken Bigley's wife mourns the loss of her husband] – [[BBC News]] |

||

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3683182.stm |

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3683182.stm Profile:Kenneth Bigley], [[BBC News]], 10 October 2004 |

||

* [http://observer.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,6903,1355798,00.html "Theatre of terror"], by Jason Burke, ''The Observer'', 21 November 2004 |

* [http://observer.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,6903,1355798,00.html "Theatre of terror"], by Jason Burke, ''[[The Observer]]'', 21 November 2004 |

||

* [http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2087-1302700,00.html "Bigley beheaded after MI6 rescue backfired"], by Hala Jaber and Ali Rifat, ''The Sunday Times'', 10 October 2004 |

* [http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2087-1302700,00.html "Bigley beheaded after MI6 rescue backfired"], by Hala Jaber and Ali Rifat, ''[[The Sunday Times]]'', 10 October 2004 |

||

* [ |

* [https://www.theguardian.com/women/story/0,3604,1220673,00.html "The other prisoners"] by Luke Harding, ''[[The Guardian]]'', 20 May 2004 |

||

* [ |

* [https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/1477202/Ken-Bigleys-hostage-cage-found.html "Ken Bigley's hostage cage 'found'"], no byline, ''[[The Daily Telegraph]]'', 22 November 2004 |

||

* [ |

* [https://www.theguardian.com/Iraq/Story/0,2763,1350982,00.html "The final battle"] by Peter Beaumont, ''[[The Observer]]'', 14 November 2004 |

||

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/4933490.stm "Bigley body claims investigated"] |

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/4933490.stm "Bigley body claims investigated"] [[BBC News]], 22 April 2006 |

||

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/3749548.stm "Spectator apology for 'disproportionate grief' for Mr Bigley"] |

* [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/3749548.stm "Spectator apology for 'disproportionate grief' for Mr Bigley"] [[BBC News]], 16 October 2004 |

||

*"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/talking_point/3726732.stm Ken Bigley killed: Your reaction]." |

*"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/talking_point/3726732.stm Ken Bigley killed: Your reaction]." [[BBC]]. Thursday 14 October 2004. |

||

{{authority control}} |

|||

{{Persondata <!-- Metadata: see [[Wikipedia:Persondata]]. --> |

|||

| NAME = Bigley, Kenneth |

|||

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES = |

|||

| SHORT DESCRIPTION = |

|||

| DATE OF BIRTH = 22 April 1942 |

|||

| PLACE OF BIRTH = |

|||

| DATE OF DEATH = 7 October 2004 |

|||

| PLACE OF DEATH = |

|||

}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bigley, Kenneth}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bigley, Kenneth}} |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Iraq–United Kingdom relations]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:2000s missing person cases]] |

||

[[Category:2004 murders in Iraq]] |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Deaths by person in Iraq]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Filmed executions in Iraq]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Islamism-related beheadings]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Missing person cases in Iraq]] |

||

[[Category:Foreign hostages in Iraq]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Liverpool]] |

|||

[[Category:British people taken hostage]] |

|||

[[Category:British terrorism victims]] |

|||

[[Category:Terrorism deaths in Iraq]] |

[[Category:Terrorism deaths in Iraq]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Beheading videos]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:War crimes in the Iraq War]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:2004 in Baghdad]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:British people of the Iraq War]] |

||

[[Category:October 2004 crimes]] |

|||

[[Category:October 2004 events in Iraq]] |

|||

[[ar:كينيث بجلي]] |

|||

[[Category:Terrorist incidents in Iraq in 2004]] |

|||

[[fi:Kenneth Bigley]] |

|||

[[Category:Kidnapping in Iraq]] |

|||

[[Category:Kidnapping in the 2000s]] |

|||

Revision as of 21:51, 18 April 2024

Kenneth Bigley | |

|---|---|

Bigley (right) with his wife Sombat in 1998 | |

| Born | Kenneth John Bigley 22 April 1942 |

| Died | 7 October 2004 (aged 62) Baghdad, Iraq |

| Cause of death | Decapitation |

| Nationality | British |

Kenneth John Bigley (22 April 1942 – 7 October 2004) was a British civil engineer who was kidnapped by Islamic extremists in the al-Mansour district of Baghdad, Iraq, on 16 September 2004, along with his colleagues, U.S. citizens Jack Hensley and Eugene Armstrong. Following the murders of Hensley and Armstrong by beheading over the course of three days, Bigley was killed in the same manner two weeks later, despite the attempted intervention of the Muslim Council of Britain and the indirect intervention of the British government. Videos of the killings were posted on websites and blogs.[1]

Capture

The three men were working for Gulf Supplies and Commercial Services, a Kuwaiti company working on reconstruction projects in Iraq. The men knew their home was being watched and realised they were in great danger when their Iraqi house guard informed them he was leaving due to threats by militias for protecting American and British workers. Bigley and the two Americans decided it was worth the risk and continued to live in the house until their abduction on 16 September.

On 18 September, the Tawhid and Jihad ("Oneness of God and Jihad") Islamic extremist group, led by Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, released a video of the three men kneeling in front of a Tawhid and Jihad banner. The kidnappers said they would kill the men within 48 hours if their demands for the release of Iraqi women prisoners held by coalition forces were not met. Armstrong was killed on 20 September when the deadline expired, Hensley 24 hours later.[1]

Negotiations for release

After Armstrong and Hensley were killed, the British government and media responded by turning Bigley's fate into Britain's major political issue during this period, leading to subsequent claims that the government had become a hostage to the situation. The British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw and the Prime Minister Tony Blair personally contacted the Bigley family several times to assure them that everything possible was being done, short of direct negotiation with the kidnappers. It was also reported that a Special Air Service (SAS) team had been placed on standby in Iraq in the event that a rescue mission might become possible.[citation needed]

The British government issued a statement saying it held no Iraqi women prisoners, and that the only two women known to be in US custody were two so-called high-profile Iraqi scientists, British-educated Rihab Taha and US-educated Huda Salih Mahdi Ammash. Both women participated in Iraq's biological-weapons programme, according to the United Nations weapons inspectorate. News reports had earlier suggested that other Iraqi women were indeed being held in US custody, but it is not known to what extent these reports were out-of-date by the time of Bigley's kidnap.[2] The Iraqi provisional government stated that Taha and Ammash could be released immediately, stressing that this was about to happen anyway, as no charges had been brought against the women.[citation needed]

Second and third videos

A second beheading video was released on 22 September by Bigley's captors, this time showing Bigley pleading for his life and begging the British Prime Minister Tony Blair to save him. Clearly exhausted and highly emotional, Bigley spoke directly to Blair: "I need you to help me now, Blair, because you are the only person on God's earth who can help me."[1] The video was posted on several websites, blogs and shown on Al Jazeera television.

Around this time it emerged that Bigley's mother Lil (then 86 years old) had been born in Dublin and was therefore entitled to be a citizen of the Republic of Ireland; this meant Bigley himself was also an Irish citizen from birth. It was hoped this status would aid his release, as Ireland did not participate in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the Irish Government issued Bigley an Irish passport in absentia,[1] which was shown on Al Jazeera television. The Irish Labour Party spokesman on foreign affairs, Michael D. Higgins, made an appeal on al-Jazeera. Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams made two appeals, one on 30 September and a second on 7 October.[1]

On 24 September, 50,000 leaflets prepared by the British Foreign Office, asking for information about Bigley's whereabouts, were distributed in al-Mansour, the wealthy district of Baghdad Bigley had been living in. In his home town of Liverpool, Christian and Muslim religious and civic leaders held joint prayer sessions for his safe return. The Muslim Council of Britain condemned the kidnapping, saying it was contrary to the teachings of the Qur'an and sent a senior two-man delegation to Iraq on 26 September to negotiate on Bigley's behalf.[1]

Bigley's family, particularly his brother Paul, was successful, with the help of the Irish government, in eliciting support for Bigley's release from Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, King Abdullah of Jordan, and Colonel Gaddafi of Libya, who made public statements. A third video was released on 29 September, showing Bigley chained inside a small chicken-wire cage, wearing an orange boiler suit apparently intended to be reminiscent of those worn by inmates at the US detainment facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In the video, Bigley again begged for his life, saying, "Tony Blair is lying. He doesn't care about me. I'm just one person." On 1 October, another 100,000 leaflets asking for information about Bigley were distributed by the British consulate in Baghdad.[1]

Death

Despite the efforts to save him, Bigley was beheaded on 7 October 2004. His death was first reported on Abu Dhabi television the following day.[3] A multi-faith memorial service, attended by Tony Blair and his wife Cherie, was held for him in Liverpool on 13 November 2004. His body has not been recovered, although an alleged al-Qaeda terrorist awaiting trial for the 2003 Istanbul bombings has claimed he is "buried in a ditch at the entrance to Fallujah".[4]

The kidnappers made a film apparently showing Bigley's murder, and the tape was subsequently posted on Islamist websites and on one shock site. According to reporters who watched the film, Bigley was wearing an orange jumpsuit, and read out a statement, before one of the kidnappers stepped forward and cut off his head with a knife. The bloodied head was then placed on top of Bigley's abdomen. News reports published after Bigley's death suggested he had briefly managed to escape from the kidnappers with the help of two MI6 agents of Syrian and Iraqi origin, who paid two of his captors to help him.[5] The captors attempted to drive Bigley, who was carrying a gun and was disguised, out of town, the reports said, but he was spotted and recaptured at an insurgent checkpoint. The two captors were purportedly executed shortly thereafter.[5]

Torture-chamber discovery

The chicken-wire cage in which Bigley was filmed was found in November 2004 by US troops in a house in Fallujah during the Second Battle of Fallujah. The US military stated that, in 20 houses, it found paraphernalia associated with hostage-holding and torture, including shackles, blood-stained walls, and a torture chamber.[6]

The Spectator controversy

Boris Johnson, the then editor of The Spectator, was criticised for an editorial, written by Simon Heffer, which appeared in the magazine on 16 October 2004 following the death of Bigley in Iraq, in which it was claimed that the response to Bigley's killing was fuelled by the fact he was from Liverpool, and went on to criticize the "drunken" fans at Hillsborough and call on them to accept responsibility for their "role" in the Hillsborough stadium disaster in 1989:

The extreme reaction to Mr Bigley's murder is fed by the fact that he was a Liverpudlian. Liverpool is a handsome city with a tribal sense of community. A combination of economic misfortune — its docks were, fundamentally, on the wrong side of England when Britain entered what is now the European Union — and an excessive predilection for welfarism have created a peculiar, and deeply unattractive, psyche among many Liverpudlians. They see themselves whenever possible as victims, and resent their victim status; yet at the same time they wallow in it. Part of this flawed psychological state is that they cannot accept that they might have made any contribution to their misfortunes, but seek rather to blame someone else for it, thereby deepening their sense of shared tribal grievance against the rest of society. The deaths of more than 50 Liverpool football supporters at Hillsborough in 1989 was undeniably a greater tragedy than the single death, however horrible, of Mr Bigley; but that is no excuse for Liverpool's failure to acknowledge, even to this day, the part played in the disaster by drunken fans at the back of the crowd who mindlessly tried to fight their way into the ground that Saturday afternoon. The police became a convenient scapegoat, and the Sun newspaper a whipping-boy for daring, albeit in a tasteless fashion, to hint at the wider causes of the incident.[7]

Johnson apologised at the time of the article, travelling to Liverpool to do so,[8] and again following the publication of the report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel in 2012; however, Johnson's apology was rejected by Margaret Aspinall, chairperson of the Hillsborough Families Support Group, whose son James, 18, died in the disaster:

What he has got to understand is that we were speaking the truth for 23 years and apologies have only started to come today from them because of yesterday. It's too little, too late. It's fine to apologise afterwards. They just don't want their names in any more sleaze. No, his apology doesn't mean a thing to me.[9]

See also

- Beheading video

- Daniel Pearl

- Fabrizio Quattrocchi

- Human rights situation in post-Saddam Iraq

- Kim Sun-il

- List of kidnappings

- List of solved missing person cases

- Nick Berg

- Paul Marshall Johnson, Jr.

- Piotr Stańczak

- Seif Adnan Kanaan

- Shosei Koda

- Steven Vincent

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Timeline: Ken Bigley". BBC News. 8 October 2004. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Harding, Luke (20 May 2004). "The other prisoners". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Wong, Edward (8 October 2004). "British Hostage Is Beheaded in Iraq". New York Times.

- ^ "Bigley body claims investigated". BBC News. 22 April 2006.

- ^ a b Jaber, Hala (10 October 2004). "Bigley beheaded after MI6 rescue backfired". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. (subscription required for full article)

- ^ Henry, Emma (17 January 2007). "Man questioned over Ken Bigley murder". The Telegraph. London.

- ^ "Bigley's fate". The Spectator.

- ^ Echo, Liverpool (13 September 2012). "Hillsborough: Boris Johnson apologises for slurs in 2004 Spectator article (VIDEO)". Liverpool Echo.

- ^ "Mayor makes Hillsborough apology". BBC News. 13 September 2012.

External links

- Ken Bigley's wife mourns the loss of her husband – BBC News

- Profile:Kenneth Bigley, BBC News, 10 October 2004

- "Theatre of terror", by Jason Burke, The Observer, 21 November 2004

- "Bigley beheaded after MI6 rescue backfired", by Hala Jaber and Ali Rifat, The Sunday Times, 10 October 2004

- "The other prisoners" by Luke Harding, The Guardian, 20 May 2004

- "Ken Bigley's hostage cage 'found'", no byline, The Daily Telegraph, 22 November 2004

- "The final battle" by Peter Beaumont, The Observer, 14 November 2004

- "Bigley body claims investigated" BBC News, 22 April 2006

- "Spectator apology for 'disproportionate grief' for Mr Bigley" BBC News, 16 October 2004

- "Ken Bigley killed: Your reaction." BBC. Thursday 14 October 2004.

- Iraq–United Kingdom relations

- 2000s missing person cases

- 2004 murders in Iraq

- Deaths by person in Iraq

- Filmed executions in Iraq

- Islamism-related beheadings

- Missing person cases in Iraq

- Terrorism deaths in Iraq

- Beheading videos

- War crimes in the Iraq War

- 2004 in Baghdad

- British people of the Iraq War

- October 2004 crimes

- October 2004 events in Iraq

- Terrorist incidents in Iraq in 2004

- Kidnapping in Iraq

- Kidnapping in the 2000s