The Pittsburgh Press: Difference between revisions

Cleanup |

m ce in lead |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''The Pittsburgh Press''''' (formerly '''''The Pittsburg Press''''' and originally '''''The Evening Penny Press''''') was a major afternoon daily newspaper published in [[Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania]], |

'''''The Pittsburgh Press''''' (formerly '''''The Pittsburg Press''''' and originally '''''The Evening Penny Press''''') was a major afternoon daily newspaper published in [[Pittsburgh|Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania]], United States, from 1884 to 1992. At one time, the ''Press'' was the second largest newspaper in [[Pennsylvania]], behind only ''[[The Philadelphia Inquirer]]''. For four years starting in 2011, the brand was revived and applied to an afternoon [[online newspaper|online edition]] of the ''[[Pittsburgh Post-Gazette]]''. |

||

==Early history== |

==Early history== |

||

Revision as of 02:32, 20 July 2021

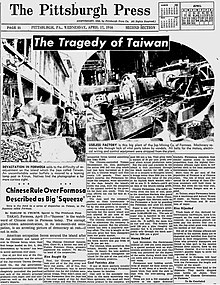

Page from the April 17, 1946, edition | |

| Type | Afternoon Daily newspaper (historical) Afternoon Daily online newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Owner(s) | E. W. Scripps Company (1923–1992) Block Communications (2011–2015) |

| Founded | June 23, 1884 |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | July 28, 1992 (in print) |

| Relaunched | November 14, 2011–September 25, 2015 |

| Headquarters | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Website | press.post-gazette.com |

The Pittsburgh Press (formerly The Pittsburg Press and originally The Evening Penny Press) was a major afternoon daily newspaper published in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, from 1884 to 1992. At one time, the Press was the second largest newspaper in Pennsylvania, behind only The Philadelphia Inquirer. For four years starting in 2011, the brand was revived and applied to an afternoon online edition of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Early history

The history of the Press traces back to an effort by Thomas J. Keenan Jr. to buy The Pittsburg Times newspaper, at which he was employed as city editor. Joining Keenan in his endeavor were reporter John S. Ritenour of the Pittsburgh Post, Charles W. Houston of the city clerk's office, and U.S. Representative Thomas M. Bayne.[1] After examining the Times and finding it in a poor state, the group changed course and decided to start a new penny paper in hopes that it would flourish in a local market full of two- and three-cent dailies.[2] The first issue appeared on June 23, 1884.[3] A corporation was formed, with Bayne as the largest shareholder.[1]

Originally The Evening Penny Press, the title changed to The Pittsburg Press (without an 'h' at the end of "Pittsburg") on October 19, 1887.[4][5] The paper referred to the city as "Pittsburg" until August 1921, when the letter 'h' was added.[6]

In 1901, Keenan, who had by then gained financial and editorial control of the paper, sold out to a syndicate led by Oliver S. Hershman.[7][8] Hershman remained the controlling owner until selling to the Scripps-Howard chain in 1923.[9]

Joint operating agreement

In 1961, the Press entered into a Joint Operating Agreement (JOA) with the competing Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. The Post-Gazette had previously purchased and merged with the Hearst Corporation's Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph leaving just itself and the much larger Pittsburgh Press.

The JOA was to be managed by the Pittsburgh Press owners (E. W. Scripps Company) as the Press had the larger circulation and was the stronger of the two papers.

Under the JOA, the Post-Gazette became a 6-day morning paper, and the Pittsburgh Press became a 6-day afternoon paper in addition to publishing the sole Sunday paper.

Sunday edition

The Sunday edition was popular with readers because of its two comics sections, which included Prince Valiant, Peanuts, Dick Tracy, Blondie, Gordo, Priscilla's Pop, and Jest in Pun, among many others, and because of the four inserted magazines: Press TV Guide, Family, Roto, and Weekly.

1992 strike, sale to the Post-Gazette

On October 22, 1991, Press management announced major changes, designed to modernize its distribution system, at the initial bargaining with the Teamsters Local 211 union, as well as eight other unions. The unions' contracts with the Press were set to expire on December 31. Negotiations continued into 1992 with no agreement on a new contract. The Teamsters employees finally walked off the job on May 17, effectively putting a halt to the publication of the Press and the Post-Gazette.[10] The Teamsters refused to drive the small delivery trucks more than half full. In the press room was a union featherbedding provision under which its members had to set up every ad that appeared in the newspaper, even if it ran years before; in the case of ads prepared by outside print shops, those ads were still set up in the type the Press had, a proof run, and then dismantled, the backlog of such ads could be several years long. With the increasing rise of electronic media, and more younger readers not reading newspapers, the Press could no longer sustain the union practices of the past. The unions wouldn't budge, didn't believe management that the previous model of doing business could no longer be sustained and afforded. A short sound bite on national TV by the then mayor, supporting the unions, was the death knell, and Scripps-Howard consequently ended the newspaper. Not only were all the union jobs lost, so were the jobs of over 100 non-union employees of the newspaper.

An attempt by both papers to resume distribution, with replacement drivers, began with the July 27 issues of both papers, and lasted two days, until they halted publication again due to resistance from the public and civic leaders.[11] The second day, July 28, marked the final edition of the Press.[5]

After months of failed negotiations, Scripps put the Pittsburgh Press up for sale on October 2, 1992. Block Communications, the owners of the much smaller JOA paper, the Post-Gazette, agreed to purchase the paper, effective November 30, upon the settlement of the strike.[11] The first issue of the newly combined Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the first in nearly six months, was published on January 18, 1993, as a single combined newspaper incorporating many features and personnel from the Press, which would no longer be published.[12]

In return for the sale of the Press, Scripps received The Monterey County Herald. The sale required a ruling by the U.S. Department of Justice as the JOA was regulated by the Newspaper Preservation Act of 1970.

Resurrection online

Block Communications announced on November 14, 2011 that it was bringing back the Press in an online-only edition for the afternoon, effective immediately. David Shribman, executive editor of the Post-Gazette, explained his paper's motivation for reviving the Press name, citing the fact that his newspaper still received letters to the editor addressed to the Press instead of the Post-Gazette, and that despite nearly 20 years since its last publication Pittsburgh natives still talked about the Press on a regular basis. Although published electronically, the new Press was formatted with a fixed layout replicating that of a traditional printed newspaper.[13] The experiment ended with the issue of September 25, 2015.[14]

See also

- List of defunct newspapers of the United States

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, current owner of the "Press" name and present-day heir to its archives.

- Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations

References

- ^ a b Swetnam, George (June 15, 1959). "The Pittsburgh Press Story—75 Years Of Civic Enterprise [Part 1]". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 17.

- ^ Thomas, Clarke M. (2005). Front-Page Pittsburgh: Two Hundred Years of the Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-8229-4248-8.

- ^ Thomas, Clarke M. (2005). Front-Page Pittsburgh: Two Hundred Years of the Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-8229-4248-8.

- ^ "About The Evening penny press". Chronicling America. Library of Congress. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ a b "About The Pittsburg press". Chronicling America. Library of Congress. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ Lowry, Patricia (July 17, 2011). "Are yinz from Pittsburg?". The Next Page. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ Swetnam, George (June 17, 1959). "The Pittsburgh Press Story—75 Years Of Civic Enterprise [Part 3]". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 21.

- ^ Swetnam, George (June 16, 1959). "The Pittsburgh Press Story—75 Years Of Civic Enterprise [Part 2]". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 25.

- ^ Thomas, Clarke M. (2005). Front-Page Pittsburgh: Two Hundred Years of the Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-8229-4248-8.

- ^ "Chronology of 71-day paper strike". The Pittsburgh Press. July 27, 1992. p. A6.

- ^ a b McKay, Jim (January 18, 1993). "A strike no one could settle". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. A-19.

- ^ "To our readers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 18, 1993. p. A-1.

- ^ Schooley, Tim (November 14, 2011). "Block brings back Pittsburgh Press in e-version". Pittsburgh Business Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Press bids farewell". The Pittsburgh Press. September 25, 2015. p. 1. Retrieved November 27, 2015.