History of printing in East Asia: Difference between revisions

m Bot: Converting bare references, see FAQ |

→See also: Dyer |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

* [[movable type]] |

* [[movable type]] |

||

* [[printing press]] |

* [[printing press]] |

||

* [[Samuel Dyer]] |

|||

* [[Wang Zhen (official)]] |

* [[Wang Zhen (official)]] |

||

* [[Hua Sui]] |

* [[Hua Sui]] |

||

Revision as of 15:26, 13 February 2008

- For the article on the development of printing in Europe, see History of western typography.

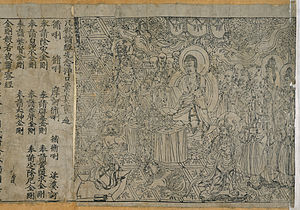

The Chinese invention of paper and woodblock printing, at some point before the first dated book in 868 (the Diamond Sutra) produced the world's first print culture: "it was the Chinese who really discovered the means of communication that was to dominate until our age."[1]

Woodblock printing was better suited to Chinese characters than movable type, which the Chinese also invented, but which did not replace woodblock printing. In China, the use of woodblock printing on paper and movable type preceded their use in Europe by several centuries. Both methods were replaced in the second half of the 19th century by Western-style printing.

Woodblock printing

Woodblock printing on paper, whereby individual sheets of paper were pressed into wooden blocks with the text and illustrations carved into them, was first recorded in Chinese history, and the oldest surviving printed book to be documented, a copy of the Buddhist Diamond Sutra, is dated 868 AD. As a method for printing patterns on cloth the earliest surviving examples from China date to before 220,[2] and from Egypt to the 4th century.[3] By the 12th and 13th centuries, many Chinese libraries contained tens of thousands of printed volumes.

The earliest woodblocks used for printing in Europe, in the fourteenth century, using exactly the same technique as Chinese woodblocks, lead some pioneering scholars of Asian subjects to hypothesize a connection: "the process of printing them must have been copied from ancient Chinese specimens, brought from that country by some early travelers, whose names have not been handed down to our times" (Robert Curzon, 1810-1873).[citation needed] Joseph Needham's Science and Civilization in China has a chapter that suggests that "European block printers must not only have seen Chinese samples, but perhaps had been taught by missionaries or others who had learned these un-European methods from Chinese printers during their residence in China."[4] [page needed]

But historians of the Western prints themselves see no need for such a direct and late connection. Rather, they assume that European woodcut appeared "spontaneously and presumably as a result of the use of paper as it had been observed that paper was better suited than rough-surfaced parchment for making the impressions from wood-reliefs".[5] Also, Hyatt Mayor:

- A little before 1400 Europeans had enough paper to begin making holy images and playing cards in woodcut. They need not have learned woodcut from the Chinese, because they had been using woodblocks for about 1,000 years to stamp designs on linen.[6]

European woodblock printing shows a clear progression from patterns to images, both printed on cloth, then to images printed on paper, when it became widely available in Europe in about 1400.[7] Text and images printed together only appear some sixty years later, after metal movable type[8]

Movable type

Movable type in China

The first known movable type system was invented in China around 1040 AD by Bi Sheng (990-1051).[9] Bi Sheng's type was made of baked clay. As described by the Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (1031–1095):

- When he wished to print, he took an iron frame and set it on the iron plate. In this he placed the types, set close together. When the frame was full, the whole made one solid block of type. He then placed it near the fire to warm it. When the paste [at the back] was slightly melted, he took a smooth board and pressed it over the surface, so that the block of type became as even as a whetstone.

- For each character there were several types, and for certain common characters there were twenty or more types each, in order to be prepared for the repetition of characters on the same page. When the characters were not in use he had them arranged with paper labels, one label for each rhyme-group, and kept them in wooden cases.[10]

However, Bi Sheng's fragile clay types were not practical for large-scale printing.[11] Clay types also have the additional handicap of lacking adhesion to the ink.

Wooden movable type

Wooden movable type was developed by the late 13th century, pioneered by Wang Zhen, author of the Nong Shu (農書).[12] Although the wooden type was more durable under the mechanical rigors of handling, repeated printing wore the character faces down, and the types could only be replaced by carving new pieces. This system was later enhanced by pressing wooden blocks into sand and casting metal types from the depression in copper, bronze, iron or tin.[citation needed] The set of wafer-like metal stamp types could be assembled to form pages, inked, and page impressions taken from rubbings on cloth or paper.[citation needed] Before the pioneer of bronze-type printing of China, Hua Sui in 1490 AD, Wang Zhen had experimented with metal type using tin, yet found it unsatisfactory due to its incompatibility with the inking process.[13]

A particular difficulty posed the logistical problems of handling the several thousand logographs whose command is required for full literacy in Chinese language. It was faster to carve one woodblock per page than to composit a page from so many different types.[9] However, if one was to use movable type for multitudes of the same document, the speed of printing would be relatively quicker.[9]

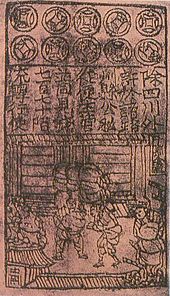

Later in the Jin Dynasty, people used the same but more developed technique to print paper money and formal official documents. The typical example of this kind of movable copper-block printing is a printed "check" of Jin Dynasty in the year of 1215.

Movable type in Korea

The transition from wood type to movable metal type occurred in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty, sometime in the thirteenth century, to meet the heavy demand for both religious and secular books. A set of ritual books, Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun were printed with movable metal type in 1234.[14] [page needed] The credit for the first metal movable type may go to Choe Yun-ui of the Goryeo Dynasty in 1234.[15]

Examples of this metal type are on display in the Asian Reading Room of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.[16] The oldest extant movable metal print book is the Jikji, printed in Korea in 1377.[17]

The techniques for bronze casting, used at the time for making coins (as well as bells and statues) were adapted to making metal type. Unlike the metal punch system thought to be used by Gutenberg, the Koreans used a sand-casting method. The following description of the Korean font casting process was recorded by the Joseon dynasty scholar Song Hyon (15th c.):

- At first, one cuts letters in beech wood. One fills a trough level with fine sandy [clay] of the reed-growing seashore. Wood-cut letters are pressed into the sand, then the impressions become negative and form letters [molds]. At this step, placing one trough together with another, one pours the molten bronze down into an opening. The fluid flows in, filling these negative molds, one by one becoming type. Lastly, one scrapes and files off the irregularities, and piles them up to be arranged.[18]

Among books printed with metal movable type, the oldest surviving books are from Korea, dated at least from 1377.[19] However, Korea never witnessed a printing revolution comparable to Europe's:

- Korean printing with movable metallic type developed mainly within the royal foundry of the Yi dynasty. Royalty kept a monopoly of this new technique and by royal mandate suppressed all non-official printing activities and any budding attempts at commercialization of printing. Thus, printing in early Korea served only the small, noble groups of the highly stratified society.[20]

A potential solution to the linguistic and cultural bottleneck that held back movable type in Korea for two hundred years appeared in the early 15th century—a generation before Gutenberg would begin working on his own movable type invention in Europe—when King Sejong devised a simplified alphabet of 24 characters called Hangul for use by the common people, which could have made the typecasting and compositing process more feasible. But King Sejong's brilliant creation did not receive the attention it deserved. Adoption of the new alphabet was stifled by the inertia of Korea's cultural elite, who were "appalled at the idea of losing Chinese, the badge of their elitism."[citation needed]

Separately invented in China, metal movable type was also pioneered by Hua Sui in 1490 AD, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD).[21]

Movable type in Japan

Though the Jesuits operated a Western movable type printing-press in Nagasaki, Japan, printing equipment[22] brought back by Toyotomi Hideyoshi's army in 1593 from Korea had far greater influence on the development of the medium. Four years later, Tokugawa Ieyasu, even before becoming shogun, effected the creation of the first native movable type,[22] [page needed] using wooden type-pieces rather than metal. He oversaw the creation of 100,000 type-pieces, which were used to print a number of political and historical texts.

An edition of the Confucian Analects was printed in 1598, using Korean moveable type printing equipment, at the order of Emperor Go-Yōzei. This document is the oldest work of Japanese moveable type printing extant today. Despite the appeal of moveable type, however, it was soon decided that the running script style of Japanese writings would be better reproduced using woodblocks, and so woodblocks were once more adopted; by 1640 they were once again being used for nearly all purposes.[23] [page needed]

Movable type in other East Asian countries

Printing using movable type spread from China during the Mongol Empire; among other groups, the Uyghurs of Central Asia, whose script was adopted for the Mongol language, used movable type.[4]

Possible influence on European use of movable type

Since the use of printing from movable type arose in East Asia well before it did in Europe, it is relevant to ask whether Gutenberg may have been influenced, directly or indirectly, by the Chinese or Korean discoveries of movable type printing. There is no actual evidence that Gutenberg may have known of the Korean processes for movable type.[14] However, some authors admit this possibility, and argue that movable metal type had been an active enterprise in Korea since 1234 (although oldest preserved books are from 1377) and there was communication between West and East.[14]. [page needed] Despite these conjectures, there is no evidence that movable type from the East ever reached Europe.

Mechanical presses

Mechanical presses as used in European printing remained unknown in East Asia.[24] [25] Instead, printing remained an unmechanized, laborious process with pressing the back of the paper onto the inked block by manual "rubbing" with a hand tool.[7] In Korea, the first printing presses were introduced as late as 1881-83[26] [27], while in Japan, after an early but brief interlude in the 1590s[28], Gutenberg's printing press arrived in Nagasaki in 1848 on a Dutch ship.[29]

Contrary to Gutenberg printing, which allowed printing on both sides of the paper from its very beginnings (although not simultaneously until very recent times), East Asian printing was done only on one side of the paper, because the need to rub the back of the paper when printing would have spoilt the first side when the second side was printed.[7] Another reason was that, unlike in Europe where Gutenberg introduced more suitable oil-based ink, Asian printing remained confined to water-based inks which tended to soak through the paper.

Notes

- ^ A Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos 1-4. ISBN 0691003262

- ^ Shelagh Vainker in Anne Farrer (ed), "Caves of the Thousand Buddhas", p.112, 1990, British Museum publications, ISBN 0 7141 1447 2

- ^ Ancient Coptic Christian Fabrics from Egypt

- ^ a b

Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). "part one, vol.5". In Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, (ed.). Paper and Printing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved April 8 2007, from Encyclopaedia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite DVD – entry 'printing'

- ^ A. Hyatt Mayor, "A Historical Survey of Printmaking", Art Education, Vol. 17, No. 4. (Apr., 1964), pp. 4-9 (4)

- ^ a b c An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, Arthur M. Hind, p 64-127 , Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- ^ Master E.S., cat nos 4-15, Alan Shestack, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1967

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 201.

- ^ Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). "part one, vol.5", in Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China,: Paper and Printing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Page 201-202.

- ^ Sohn, Pow-Key, "Early Korean Printing," Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 79, No. 2 (Apr.-Jun., 1959), pp.96-103 (100)

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 206.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 217.

- ^ a b c Thomas Christensen (2006). "Did East Asian Printing Traditions Influence the European Renaissance?". Arts of Asia Magazine (to appear). Retrieved 2006-10-18. Cite error: The named reference "christensen" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Baek Sauk Gi (1987). Woong-Jin-Wee-In-Jun-Gi #11 Jang Young Sil, page 61. Woongjin Publishing.

- ^ World Treasures of the Library of Congress. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ^ Michael Twyman, The British Library Guide to Printing: History and Techniques, London: The British Library, 1998 [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0802081797&id=KXoaalwyOjAC&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=korea+gutenberg+surviving&sig=4QBhy9ty1jbXJASJcUzFBDfKbGo online]

- ^ Sohn, Pow-Key (1993). "Printing Since the 8th Century in Korea". Koreana. 7 (2): 4–9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Michael Twyman, The British Library Guide to Printing: History and Techniques, London: The British Library, 1998 [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0802081797&id=KXoaalwyOjAC&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=korea+gutenberg+surviving&sig=4QBhy9ty1jbXJASJcUzFBDfKbGo available online]

- ^ Sohn, Pow-Key, "Early Korean Printing," Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 79, No. 2 (Apr.-Jun., 1959), pp.96-103 (103)

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 212.

- ^ a b Lane, Richard (1978). "Images of the Floating World." Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. p33.

- ^ Sansom, George (1961). "A History of Japan: 1334-1615." Stanford, California: Stanford University Press

- ^ Ricardo Duchesne, "Asia First?", The Journal of the Historical Society, Vol. 6, Issue 1 (March 2006), pp.69-91 (83) (PDF)

- ^ printing. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 5, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD

- ^ Albert A. Altman, "Korea's First Newspaper: The Japanese Chosen shinpo", The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 4. (Aug., 1984), pp. 685-696

- ^ Melvin McGovern, "Early Western Presses in Korea", Korea Journal, 1967, pp.21-23

- ^ Akihiro Kinoshita, Keiichi Ishikawa, “Early Printing History in Japan”, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Volume 73.1998 (1998), pp. 30-35 (34)

- ^ Akihiro Kinoshita, Keiichi Ishikawa, “Early Printing History in Japan”, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Volume 73.1998 (1998), pp. 30-35 (33f.)

General references and further reading

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 1. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985 also published in Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986.

- also referred to as:

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin, '"Paper and Printing," vol. 5 part 1 of Needham, Joseph Science and Civilization in China:. Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0521086906. also published in Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986.

- Twitchett, Denis. Printing and Publishing in Medieval China., New York, Frederick C. Beil, 1983.

- Carter, Thomas Frances. The Invention of Printing in China and its spread Westward" 2nd ed., revised by L. Carrington Goodrich. NY:Ronald Press, 19355. (1st ed, 1925)