Solar thermal energy

Solar thermal energy (or STE)[1] is a technology for harnessing solar energy for heat. Solar thermal collectors are characterized by the US Energy Information Agency as low, medium, or high temperature collectors. Low temperature collectors are flat plates generally used to heat swimming pools. Medium-temperature collectors are also usually flat plates but are used for creating hot water for residential and commercial use. High temperature collectors concentrate sunlight using mirrors or lenses and are generally used for electric power production. This is different from solar photovoltaics, which convert solar energy directly into electricity.

Low-temperature collectors

Of the 21,000,000 square feet (2,000,000 m2) of solar thermal collectors produced in the United States in 2006, 16,000,000 square feet (1,500,000 m2) were of the low-temperature variety.[2] Low-temperature collectors are generally installed to heat swimming pools, although they can also be used for space heating. Collectors can use air or water as the medium to transfer the heat to its destination.

Heating, cooling, and ventilation

In the United States, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems account for over 25 percent (4.75 EJ) of the energy used in commercial buildings and nearly half (10.1 EJ) of the energy used in residential buildings.[3][4] Solar heating, cooling, and ventilation technologies can be used to offset a portion of this energy.

Thermal mass materials store solar energy during the day and release this energy during cooler periods. Common thermal mass materials include stone, cement, and water. The proportion and placement of thermal mass should consider several factors such as climate, daylighting, and shading conditions. When properly incorporated, thermal mass can passively maintain comfortable temperatures while reducing energy consumption.

A solar chimney (or thermal chimney) is a passive solar ventilation system composed of a hollow thermal mass connecting the interior and exterior of a building. As the chimney warms, the air inside is heated causing an updraft that pulls air through the building. These systems have been in use since Roman times and remain common in the Middle East.

A Trombe wall is a passive solar heating and ventilation system consisting of an air channel sandwiched between a window and a sun-facing thermal mass. During the ventilation cycle, sunlight stores heat in the thermal mass and warms the air channel causing circulation through vents at the top and bottom of the wall. During the heating cycle the Trombe wall radiates stored heat.[5]

Solar roof ponds are a unique solar heating and cooling technology developed by Harold Hay in the 1960s. A basic system consists of a roof mounted water bladder with a movable insulating cover. This system can control heat exchange between interior and exterior environments by covering and uncovering the bladder between night and day. When heating is a concern the bladder is uncovered during the day allowing sunlight to warm the water bladder and store heat for evening use. When cooling is a concern the covered bladder draws heat from the building's interior during the day and is uncovered at night to radiate heat to the cooler atmosphere. The Skytherm house in Atascadero, California uses a prototype roof pond for heating and cooling.[6]

Active solar cooling can be achieved via absorption refrigeration cycles, desiccant cycles, and solar mechanical processes. In 1878, Auguste Mouchout pioneered solar cooling by making ice using a solar steam engine attached to a refrigeration device.[7] Thermal mass, smart windows and shading methods can also be used to provide cooling. The leaves of deciduous trees provide natural shade during the summer while the bare limbs allow light and warmth into a building during the winter. The water content of trees will also help moderate local temperatures.

Process heat

Evaporation ponds are shallow ponds that concentrate dissolved solids through evaporation. The use of evaporation ponds to obtain salt from sea water is one of the oldest applications of solar energy. Modern uses include concentrating brine solutions used in leach mining and removing dissolved solids from waste streams. Altogether, evaporation ponds represent one of the largest commercial applications of solar energy in use today.[8]

Unglazed transpired collectors (UTC) are perforated sun-facing walls used for preheating ventilation air. UTCs can raise the incoming air temperature up to 22 °C and deliver outlet temperatures of 45-60 °C. The short payback period of transpired collectors (3 to 12 years) make them a more cost-effective alternative to glazed collection systems. As of 2003, over 80 systems with a combined collector area of 35,000 m² had been installed worldwide. Representatives include an 860 m² collector in Costa Rica used for drying coffee beans and a 1300 m² collector in Coimbatore, India used for drying marigolds.[9][10]

A food processing facility in Modesto, California uses parabolic troughs to produce steam used in the manufacturing process. The 5,000 m² collector area is expected to provide 4.3 GJ per year.[11]

Medium-temperature collectors

These collectors could be used to produce approximately 50% of the hot water needed for residential and commercial use in the United States.[12] In the United States, a typical system costs $5000-$6000 and 50% of the system qualifies for a tax credit. With this incentive, the payback time for a typical household is nine years. A crew of one plumber and two assistants with minimal training can install two systems per week. The typical installation has negligible maintenance costs and reduces a households' operating costs by $6 per person per month. Solar water heating can reduce CO2 emissions by 1 ton/year (if replacing natural gas for hot water heating) or 3 ton/year (if replacing electric hot water heating).[13] Medium-temperature installations can use any of several designs: common designs are pressurized glycol, drain back, and batch systems.

Cooking

Solar cookers use sunlight for cooking, drying and pasteurization. Solar cooking offsets fuel costs, reduces demand for fuel or firewood, and improves air quality by reducing or removing a source of smoke.

The simplest type of solar cooker is the box cooker first built by Horace de Saussure in 1767. A basic box cooker consists of an insulated container with a transparent lid. These cookers can be used effectively with partially overcast skies and will typically reach temperatures of 50-100 °C.[14][15]

Concentrating solar cookers use reflectors to concentrate light on a cooking container. The most common reflector geometries are flat plate, disc and parabolic trough type. These designs cook faster and at higher temperatures (up to 350 °C) but require direct light to function properly.

The Solar Kitchen in Auroville, India uses a unique concentrating technology known as the solar bowl. Contrary to conventional tracking reflector/fixed receiver systems, the solar bowl uses a fixed spherical reflector with a receiver which tracks the focus of light as the Sun moves across the sky. The solar bowl's receiver reaches temperature of 150 °C that are used to produce steam that helps cook 2,000 daily meals.[16]

Many other solar kitchen in India use another unique concentrating technology known as the Scheffler reflector. This technology was first developed by Wolfgang Scheffler in 1986. A Scheffler reflector is a parabolic dish that uses single axis tracking to follow the Sun's daily course. These reflectors have a flexible reflective surface that is able to change its curvature to adjust to seasonal variations in the incident angle of sunlight. Scheffler reflectors have the advantage of having a fixed focal point which improves the ease of cooking and are able to reach temperatures of 450-650 °C.[17] Built in 1999, the world's largest Scheffler reflector system in Abu Road, Rajasthan India is capable of cooking up to 35,000 meals a day.[18] By early 2008, over 2000 large cookers of the Scheffler design had been built worldwide.

Disinfection and desalination

Solar water disinfection, also known as SODIS, is a simple method of disinfecting water using only sunlight and plastic PET bottles.[19] SODIS is a cheap and effective method for decentralized water treatment, usually applied at the household level and is recommended by the World Health Organization as a viable method for household water treatment and safe storage.[20] SODIS has over two million users in developing countries such as Brazil, Cameroon and Uzbekistan.

A solar still uses solar energy to distill water. The main types are cone shaped, boxlike, and pit. The box shaped types are most sophisticated of these and the pit types the least sophisticated. In cone solar stills, impure water is inserted into the container, where it is evaporated by sunlight coming through clear plastic. Free of solids in suspension or solution, the water vapor condenses on top and drips down to the side, where it is collected and removed.

High-temperature collectors

Where temperatures below about 95°C are sufficient, as for space heating, flat-plate collectors of the nonconcentrating type are generally used. The fluid-filled pipes can reach temperatures of 150 to 220 degrees Celsius when the fluid is not circulating. This temperature is too low for efficient conversion to electricity.

The efficiency of heat engines increases with the temperature of the heat source. To achieve this in solar thermal energy plants, solar radiation is concentrated by mirrors or lenses to obtain higher temperatures — a technique called Concentrated Solar Power (CSP). The practical effect of high efficiencies is to reduce the plant's collector size and total land use per unit power generated, reducing the environmental impacts of a power plant as well as its expense.

As the temperature increases, different forms of conversion become practical. Up to 600°C, steam turbines, standard technology, have an efficiency up to 41%. Above this, gas turbines can be more efficient. Higher temperatures are problematic because different materials and techniques are needed. One proposal for very high temperatures is to use liquid fluoride salts operating above 1100°C, using multi-stage turbine systems to achieve 60% thermal efficiencies. [21] The higher operating temperatures permit the plant to use higher-temperature dry heat exchangers for its thermal exhaust, reducing the plant's water use — critical in the deserts where large solar plants are practical. High temperatures also make heat storage more efficient, because more watt-hours are stored per kilo of fluid.

Since the CSP plant generates heat first of all, it can store the heat before conversion to electricity. With current technology, storage of heat is much cheaper and more efficient than storage of electricity. In this way, the CSP plant can produce electricity day and night. If the CSP site has predictable solar radiation, then the CSP plant becomes a reliable power plant. Reliability can further be improved by installing a back-up system that uses fossil energy. The back-up system can reuse most of the CSP plant, which decreases the cost of the back-up system.

With reliability, unused desert, no pollution and no fuel costs, the only obstacle for large deployment for CSP is cost. Although only a small percentage of the desert is necessary to meet global electricity demand, still a large area must be covered with mirrors or lenses to obtain a significant amount of energy. An important way to decrease cost is the use of a simple design.

System designs

During the day the sun has different positions. If the mirrors or lenses do not move, then the focus of the mirrors or lenses changes. Therefore it seems unavoidable that there needs to be a tracking system that follows the position of the sun (for solar photovoltaics a solar tracker is only optional). The tracking system increases the cost. With this in mind, different designs can be distinguished in how they concentrate the light and track the position of the sun.

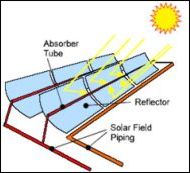

Parabolic trough designs

Parabolic trough power plants use a curved trough which reflects the direct solar radiation onto a receiver (also called absorber or collector) running along above the trough. The trough is parabolic in one direction and just straight in the other direction. For change of position of the sun orthogonal to the receiver, the whole trough tilts so that direct radiation remains focused on the receiver. However, a change of position of the sun parallel to the trough, does not require adjustment of the mirrors, since the light is just concentrated on another part of the receiver. So, the trough design avoids a second axis for tracking.

A substance (also called heat transfer fluid) passes through the receiver and becomes hot. Used substances are synthetic oil, molten salt and pressurized steam. The receiver can be in a vacuum chamber of glass. The light will shine through the glass and vacuum, but the vacuum will significantly reduce convective loss of the collected heat. The substance with the heat is transported to a heat engine where about a third of the heat is converted to electricity.

Full-scale parabolic trough systems consist of many such troughs laid out in parallel over a large area of land.

Since 1985 a solar thermal system using this principle has been in full operation in California in the United States. It is called the SEGS system.[22] Other CSP designs lack this kind of long experience and therefore it can currently be said that the parabolic trough design is the only proven CSP technology.

The Solar Energy Generating System (SEGS) is a collection of nine plants with a total capacity of 350MW. It is currently the largest operational solar system (both thermal and non-thermal). A newer plant is Nevada Solar One plant with a capacity of 64MW. Under construction are Andasol 1 and Andasol 2 in Spain with each site having a capacity of 50MW. Note however, that those plants have heat storage which requires a smaller (but better utilized) generator. With day and night operation Andasol 1 produces more energy than Nevada Solar One.

553MW new capacity is proposed in Mojava Solar Park, California.[23] Furthermore, 59MW hybrid plant with heat storage is proposed near Barstow, California [24]. Near Kuraymat in Egypt, some 40MW steam is used as input for a gas powered plant. [25][26] Finally, 25MW steam input for a gas power plant in Hassi R'mel, Algeria. [27]

Power tower designs

Power towers (also known as 'central tower' power plants or 'heliostat' power plants) use an array of flat, moveable mirrors (called heliostats) to focus the sun's rays upon a collector tower (the receiver).

The advantage of this design above the parabolic trough design is the higher temperature. Thermal energy at higher temperatures can be converted to electricity more efficiently and can be more cheaply stored for later use. Furthermore, there is less need to flatten the ground area. In principle a power tower can be built on a hillside. Mirrors can be flat and plumbing is concentrated in the tower. The disadvantage is that each mirror must have its own dual-axis control, while in the parabolic trough design one axis can be shared for a large array of mirrors.

A working tower power plant is PS10 in Spain with a capacity of 11MW.

The 15MW Solar Tres plant with heat storage is under construction in Spain. In South Africa, a 100MW solar power plant is planned with 4000 to 5000 heliostat mirrors, each having an area of 140 m².[28] A 10MW power plant in Cloncurry Australia (with purified graphite as heat storage located on the tower directly by the receiver). [29] The company BrightSourceEnergy [30] has announced plans to build 500MW's worth of solar power plants, in 3 installations, in California with the Power Tower technology of Luz II. [31]

Out of commission are the 10MW Solar One (later redeveloped and made into Solar Two) and the 2MW Themis plants.

A cost/performance comparison between power tower and parabolic trough concentrators was made by the NREL which estimated that by 2020 electricity could be produced from power towers for 5.47 ₡/kWh and for 6.21 ₡/kWh from parabolic troughs. The capacity factor for power towers was estimated to be 72.9% and 56.2% for parabolic troughs.[32] There is some hope that the development of cheap, durable, mass produceable heliostat power plant components could bring this cost down. [33]

Dish designs

A dish system uses a large, reflective, parabolic dish (similar in shape to satellite television dish). It focuses all the sunlight that strikes the dish up onto to a single point above the dish, where a receiver captures the heat and transforms it into a useful form. Typically the dish is coupled with a Stirling engine in a Dish-Stirling System, but also sometimes a steam engine is used. These create rotational kinetic energy that can be converted to electricity using an electric generator [34].

The advantage of a dish system is that it can achieve much higher temperatures due to the higher concentration of light (as in tower designs). Higher temperatures leads to better conversion to electricity and the dish system is very efficient on this point. However, there are also some disadvantages. Heat to electricity conversion requires moving parts and that results in maintenance. In general, a centralized approach for this conversion is better than the dencentralized concept in the dish design. Second, the (heavy) engine is part of the moving structure, which requires a rigid frame and strong tracking system. Furthermore, parabolic mirrors are used instead of flat mirrors and tracking must be dual-axis.

In 2005 Southern California Edison announced an agreement to purchase solar powered Stirling engines from Stirling Energy Systems over a twenty year period and in quantities (20,000 units) sufficient to generate 500 megawatts of electricity. [35] Stirling Energy Systems announced another agreement with San Diego Gas & Electric to provide between 300 and 900 megawatts of electricity.[36] However, as of October 2007 it was unclear whether any progress had been made toward the construction of the 1 MW test plant, which was supposed to come online some time in 2007. [37] [38]

Fresnel reflectors

A linear Fresnel reflector power plant uses a series of long, narrow, shallow-curvature (or even flat) mirrors to focus light onto one or more linear receivers positioned above the mirrors. On top of the receiver a small parabolic mirror can be attached for further focusing the light. These systems aim to offer lower overall costs by sharing a receiver between several mirrors (as compared with trough and dish concepts), while still using the simple line-focus geometry with one axis for tracking. This is similar to the trough design (and different from central towers and dishes with dual-axis). The receiver is stationary and so fluid couplings are not required (as in troughs and dishes). The mirrors also do not need to support the receiver, so they are structurally simpler. When suitable aiming strategies are used (mirrors aimed at different receivers at different times of day), this can allow a denser packing of mirrors on available land area.

Recent prototypes of these types of systems have been built in Australia (CLFR[39]) and Belgium (SolarMundo). Furthermore a Fresnel-based prototype with direct steam generation was built by Solar Power Group in conjunction with the German Aerospace Center (DLR[40]).

Based on the Australian prototype, a 177MW plant is proposed near San Luis Obispo in California and will be built by Ausra[41]. Plants with smaller capacities being an enormous economical challenge for plants with conventional parabolic trough and drive design, only few companies intend to build such small projects. Plans were revealed for former Ausra subsidiary SHP Europe building a 6.5 MW project in Portugal as a combined cycle plant. The German company SK Energy[42]]) has published its intention to build various small 1-3 MW plants in Southern Europe, esp. in Spain on the basis of their own Fresnel mirror and steam drive technology (Press Release[43]).

A Multi-Tower Solar Array (MTSA) concept, that uses a point-focus Fresnel reflector idea, has also been developed,[44] but has not yet been prototyped.

Linear Fresnel Reflector (LFR) and compact-LFR Technologies

Rival single axis tracking technologies include the relatively new Linear Fresnel reflector (LFR) and compact-LFR (CLFR) technologies. The LFR differs from that of the parabolic trough in that the absorber is fixed in space above the mirror field. Also, the reflector is composed of many low row segments, which focus collectively on an elevated long tower receiver running parallel to the reflector rotational axis.[45]

This system offers a lower cost solution as the absorber row is shared among several rows of mirrors. However, one fundamental difficulty with the LFR technology is the avoidance of shading of incoming solar radiation and blocking of reflected solar radiation by adjacent reflectors. Blocking and shading can be reduced by using absorber towers elevated higher or by increasing the absorber size, which allows increased spacing between reflectors remote from the absorber. Both these solutions increase costs, as larger ground usage is required.

The compact linear Fresnel reflector (CLFR) offers an alternate solution to the LFR problem.9 The classic LFR has only one linear absorber on a single linear tower. This prohibits any option of the direction of orientation of a given reflector. Since this technology would be introduced in a large field, one can assume that there will be many linear absorbers in the system. Therefore, if the linear absorbers are close enough, individual reflectors will have the option of directed reflected solar radiation to at least two absorbers. This additional factor gives potential for more densely packed arrays, since patters of alternative reflector inclination can be set up such that closely packed reflectors can be positioned without shading and blocking.[46]

CLFR power plants offer reduced costs in all elements of the solar array.[47] These reduced costs encourage the advancement of this technology. Features that enhance the cost effectiveness of this system compared to that of the parabolic trough technology include minimized structural costs, minimized parasitic pumping losses, and low maintenance.7 Minimized structural costs are attributed to the use of flat or elastically curved glass reflectors instead of costly sagged glass reflectors are mounted close to the ground. Also, the heat transfer loop is separated from the reflector field, avoiding the cost of flexible high pressure lines required in trough systems. Minimized parasitic pumping losses are due to the use of water for the heat transfer fluid with passive direct boiling. The use of glass-evacuated tubes ensures low radiative losses and is inexpensive. Studies of existing CLFR plants have been shown to deliver tracked beam to electricity efficiency of 19% on an annual basis as a preheater. [48]

Fresnel lenses

Prototypes of Fresnel lens concentrators have been produced for the collection of thermal energy by International Automated Systems. No full-scale thermal systems using Fresnel lenses are known to be in operation, although products incorporating Fresnel lenses in conjunction with photovoltaic cells are already available[49].

The advantage of this design is that lenses are cheaper than mirrors. Furthermore, if a material is chosen that has some flexibility, then a less rigid frame is required to withstand wind load.

MicroCSP

"MicroCSP"[50] references Solar Thermal Technologies in which Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) collectors are based on the designs used in traditional Concentrating Solar Power systems found in the Mojave Desert [51] but are smaller in collector size, lighter and operate at lower thermal temperatures usually below 600 degrees F. These systems are designed for modular field or rooftop installation where they are easy to protect from high winds, snow and humid deployments [52]. Solar manufacturer Sopogy is currently constructing a 1MW plant at the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii [53]

Heat exchange

Heat in a solar thermal system is guided by five basic principles: heat gain; heat transfer; heat storage; heat transport; and heat insulation.[54] Here, heat is the measure of the amount of thermal energy an object contains and is the product of temperature and mass.

Heat gain is the heat accumulated from the sun in the system. Solar thermal heat is trapped using the greenhouse effect; the greenhouse effect in this case is the ability of a reflective surface to transmit short wave radiation and reflect long wave radiation. Heat and infrared radiation (IR) are produced when short wave radiation light hits the absorber plate, which is then trapped inside the collector. Fluid, usually water, in the absorber tubes collect the trapped heat and transfers it to a heat storage vault.

Heat is transferred either by conduction or convection. When water is heated, kinetic energy is transferred by conduction to water molecules throughout the medium. These molecules spread their thermal energy by conduction and occupy more space than the cold slow moving molecules above them. The distribution of energy from the rising hot water to the sinking cold water contributes to the convection process. Heat is transferred from the absorber plates of the collector in the fluid by conduction. The collector fluid is circulated through the carrier pies to the heat transfer vault. Inside the vault, heat is transferred throughout the medium through convection.

Heat storage enables solar thermal plants to produce electricity during hours without sunlight. Heat is transferred to a thermal storage medium in an insulated reservoir during hours with sunlight, and is withdrawn for power generation during hours lacking sunlight. Thermal storage mediums will be discussed in a heat storage section. Rate of heat transfer is related to the conductive and convection medium as well as the temperature differences. Bodies with large temperature differences transfer heat faster than bodies with lower temperature differences.

Heat transport refers to the activity in which heat from a solar collector is transported to the heat storage vault. Heat insulation is vital in both heat transport tubing as well as the storage vault. It prevents heat loss, which intern relates to energy loss, or decrease in the efficiency of the system.

Heat storage

Heat storage allows a solar thermal plant to produce electricity at night and on overcast days. This allows the use of solar power for baseload generation as well as peak power generation, with the potential of displacing both coal and natural gas fired power plants. Additionally, the utilization of the generator is higher which reduces cost.

Heat is transferred to a thermal storage medium in an insulated reservoir during the day, and withdrawn for power generation at night. Thermal storage media include pressurized steam, concrete, a variety of phase change materials, and molten salts such as sodium and potassium nitrate.[55][56]

The PS10 solar power tower stores heat in tanks as pressurized steam at 50 bar and 285C. The steam condenses and flashes back to steam, when pressure is lowered. Storage is for one hour. It is suggested that longer storage is possible, but that has not been proven yet in an existing power plant. [57]

The proposed power plant in Cloncurry Australia will store heat in purified graphite. The plant has a power tower design. The graphite is located on top of the tower. Heat from the heliostats goes directly to the storage. Heat for energy production is drawn from the graphite. This simplifies the design. [58]

The Solar Tres power plant in Spain is expected to be the first commercial solar thermal power plant to utilize molten salt for heat storage and nighttime generation.[59]

Graphite heat storage

Molten salts coolants are used to transfer heat from the reflectors to heat storage vaults. The heat from the salts are transferred to a secondary heat transfer fluid via a heat exchanger and then to the storage media, or alternatively, the salts can be used to directly heat graphite. Graphite is used as it has relatively low costs and compatibility with liquid fluoride salts. The high mass and volumetric heat capacity of graphite provide an efficient storage medium.[60]

Phase-change materials for storage

Phase-change materials (PCMs) offer an alternate solution in energy storage. Using a similar heat transfer infrastructure, PCMs have the potential of providing a more efficient means of storage. PCMs can be either organic or inorganic materials. Advantages of organic PCMs include no corrosives, low or no undercooling, and chemical and thermal stability. Disadvantages include low phase-change enthalpy, low thermal conductivity, and inflammability. Inorganics are advantageous with greater phase-change enthalpy, but exhibit disadvantages with undercooling, corrosion, phase separation, and lack of thermal stability. The greater phase-change enthalpy in inorganic PCMs make hydrates salts a strong candidate in the solar energy storage field.[61]

Conversion rates from solar energy to electrical energy

Of all of these technologies the solar dish/stirling engine has the highest energy efficiency. A single solar dish-Stirling engine installed at Sandia National Laboratories National Solar Thermal Test Facility produces as much as 25 kW of electricity, with a conversion efficiency of 30%.[62]

Solar parabolic trough plants have been built with efficiencies of about 20%. Fresnel reflectors have an efficiency that is slightly lower (but this is compensated by the denser packing).

The gross conversion efficiencies (taking into account that the solar dishes or troughs occupy only a fraction of the total area of the power plant) are determined by net generating capacity over the solar energy that falls on the total area of the solar plant. The 500-megawatt (MW) SCE/SES plant would extract about 2.75% of the radiation (1 kW/m²; see Solar power for a discussion) that falls on its 4,500 acres (18.2 km²).[63] For the 50 MW AndaSol Power Plant [64] that is being built in Spain (total area of 1,300×1,500 m = 1.95 km²) gross conversion efficiency comes out at 2.6%

Furthermore, efficiency does not directly relate to cost: on calculating total cost, both efficiency and the cost of construction and maintenance should be taken into account.

Levelized cost

Since a solar power plant does not use any fuel, the cost consists mostly of capital cost with minor operational and maintenance cost. If the lifetime of the plant and the interest rate is known, then the cost per kWh can be calculated. This is called the levelized cost.

The first step in the calculation is to determine the investment for the production of 1 kWh in a year. Example, the fact sheet of the Andasol 1 project shows a total investment of 310 million euros for a production of 179 GWh a year. Since 179 GWh is 179 million kWh, the investment per kWh a year production is 310 / 179 = 1.73 euro. Another example is Cloncurry solar power station in Australia. It produces 30 million kWh a year for an investment of 31 million Australian dollars. So, this price is 1.03 Australian dollar for the production of 1 kWh in a year. This is significantly cheaper than Andasol 1, which can partially be explained by the higher radiation in Cloncurry over Spain. The investment per kwh cost for one year should not be confused with the cost per kwh over the complete lifetime of such a plant.

In most cases the capacity is specified for a power plant (for instance Andasol 1 has a capacity of 50MW). This number is not suitable for comparison, because the capacity factor can differ. If a solar power plant has heat storage, then it can also produce output after sunset, but that will not change the capacity factor, it simply displaces the output. The average capacity factor for a solar power plant, which is a function of tracking, shading and location, is about 20%, meaning that a 50MW capacity power plant will typically provide a yearly output of 50 MW x 24 hrs x 365 days x 20% = 87,600 MWh/year, or 87.6 GWh/yr.

Although the investment for one kWh year production is suitable for comparing the price of different solar power plants, it doesn't give the price per kWh yet. The way of financing has a great influence on the final price. If the technology is proven, an interest rate of 7% [65] should be possible. However, for a new technology investors want a much higher rate to compensate for the higher risk. This has a significant negative effect on the price per kWh. Independent of the way of financing, there is always a linear relation between the investment per kWh production in a year and the price for 1 kWh (before adding operational and maintenance cost). In other words, if by enhancements of the technology the investments drop by 20%, then the price per kWh also drops by 20%.

If a way of financing is assumed where the money is borrowed and repaid every year, in such way that the debt and interest decreases, then the following formula can be used to calculate the division factor: (1 - (1 + interest / 100) ^ -lifetime) / (interest / 100). For a lifetime of 25 years and an interest rate of 7%, the division number is 11.65. For example, the investment of Andasol 1 was 1.73 euro, divided by 11.65 results in a price of 0.15 euro per kWh. If one cent operation and maintenance cost is added, then the levelized cost is 0.16 euro. Other ways of financing, different way of debt repayment, different lifetime expectation, different interest rate, may lead to a significantly different number.

If the cost per kWh may follow the inflation, then the inflation rate can be added to the interest rate. If an investor puts his money on the bank for 7%, then he is not compensated for inflation. However, if the cost per kWh is raised with inflation, then he is compensated and he can add 2% (a normal inflation rate) to his return. The Andasol 1 plant has a guaranteed feed-in tariff of 0.21 euro for 25 years. If this number is fixed, it should be realized that after 25 years with 2% inflation, 0.21 euro will have a value comparable with 0.13 euro now.

Finally, there is some gap between the first investment and the first production of electricity. This increases the investment with the interest over the period that the plant is not active yet. The modular solar dish (but also solar photovoltaic and wind power) have the advantage that electricity production starts after first construction.

Given the fact that solar thermal power is reliable, can deliver peak load and does not cause pollution, a price of US$0.10 per kWh[66] starts to become competitive. Although a price of US$0.06 has been claimed [67] With some operational cost a simple target is 1 dollar (or lower) investment for 1 kWh production in a year.

History

A description of the history can be found on the site of the company Ausra.

Modern use of solar technology started after the Oil crisis in 1973 and 1979. Which resulted in the build of SEGS in California and some smaller projects.

Due to low energy prices after 1990, no new commercial plans were made, but some research was still continued.

New commercial plans were made from 2005 and onwards.

See also

- Ausra (company)

- Central solar heating plant

- Concentrating solar energy

- Energy tower

- List of solar thermal power stations

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory

- Ocean thermal energy conversion

- Renewable energy

- Solar energy

- Solar furnace

- Solar heating

- Microgeneration Certification Scheme

- Solar Heat Pump Electrical Generation System

- SK Energy (company)

- SK Energy GmbH (company)

- SkyFuel

- Solar power plants in the Mojave Desert

- Solar power tower

- Solar pond

- Solar tracker

- Solar updraft tower

- SolarPACES

- Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation

- Sopogy

References

- ^

"It's solar power's time to shine". MSN Money. Retrieved 2008-06-5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ EIA Renewable Energy- Shipments of Solar Thermal Collectors by Market Sector, End Use, and Type

- ^ "Energy Consumption Characteristics of Commercial Building HVAC Systems" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. pp. 1–6, 2–1. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ Apte, J.; et al. "Future Advanced Windows for Zero-Energy Homes" (PDF). ASHRAE. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Indirect Gain (Trombe Walls)". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ "His passion for solar still burns". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ^ Butti and Perlin (1981), p.72

- ^ Bartlett (1998), p.393-394

- ^ Leon (2006), p.62

- ^ "Solar Buildings (Transpired Air Collectors - Ventilation Preheating)" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ "Frito-Lay solar system puts the sun in SunChips, takes advantage of renewable energy". The Modesto Bee. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ^ Denholm, P. (2007). "The Technical Potential of Solar Water Heating to Reduce Fossil Fuel Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the United States" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kincaid, J. (2006). "Durham Campaign for Solar Jobs".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|accessedate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Butti and Perlin (1981), p.54-59

- ^ "Design of Solar Cookers". Arizona Solar Center. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ "The Solar Bowl". Auroville Universal Township. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ^ "Scheffler-Reflector". Solare Bruecke. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ^ "Solar Steam Cooking System". Gadhia Solar. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ^ "SODIS solar water disinfection". SANDEC. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ "Household Water Treatment and Safe Storage". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ ORNL's liquid fluoride proposal.

- ^ SEGS system

- ^ Israeli company to build largest solar park in world in US Ynetnews, 26 July 2007.

- ^ Solar thermal electric hybrid power plant for barstow

- ^ Iberdrola to build 150MW Egyptian thermal solar plant

- ^ Solar Millennium Tochter Flagsol erhält Auftrag für erstes Parabolrinnen-Kraftwerk Ägyptens

- ^ Abener Signs Contract for Solar Thermal Electric - Combined Cycle Hybrid Plant, Solarbuzz.com

- ^ 100 MW Solar Thermal Electric Project in South Africa

- ^ Cloncurry to run on solar alone

- ^ BrightSourceEnergy

- ^ Luz II

- ^ Assessment of Parabolic Trough and Power Tower Solar Technology Cost and Performance Forecasts

- ^ Google's Goal: Renewable Energy Cheaper than Coal November 27, 2007

- ^ Stirling Energy Systems Inc. - Solar Overview

- ^ World's largest solar installation to use Stirling engine technology

- ^ Stirling Energy Systems Signs New Contract for 300 MW

- ^ Questions linger over Stirling's technology as deadline looms

- ^ JUICE: Stirling Takes the Fifth

- ^ CLFR

- ^ [1]

- ^ PG&E links with Ausra for 177 megawatts of solar thermal power

- ^ [http://www.sk-energy.com

- ^ SK Energy GmbH: neuer deutscher Hersteller steigt in den Markt für kleine bis mittelgroße solarthermische Kraftwerke ein

- ^ Mills, D (2004). "Advances in solar thermal electricity technology". Solar Energy. 76 (1). Elsevier. doi:10.1016/S0038-092X(03)00102-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mills, D. "Advances in Solar Thermal Electricity Technology." Solar Energy 76 (2004): 19-31. 28 May 2008.

- ^ Mills, D, and Morrison L. Graham. "Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector Solar Thermal Powerplants." Solar Energy 68 (2000): 263-283. 28 May 2008.

- ^ Mills, D, and Morrison L. Graham. "Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector Solar Thermal Powerplants." Solar Energy 68 (2000): 263-283. 28 May 2008.

- ^ Mills, D. "Advances in Solar Thermal Electricity Technology." Solar Energy 76 (2004): 19-31. 28 May 2008.

- ^ SunCube

- ^ Hawaiian Firm Shrinks Solar Thermal Power

- ^ SEGS

- ^ MicroCSP in Idaho

- ^ Sopogy Builds a 1 megawatt MicroCSP solar thermal power plant at NELHA

- ^ Canivan, John. "Five Solar Thermal Principles." JC Solarhomes. 26 May 2008 <http://www.jc-solarhomes.com/five.htm>.

- ^ Sandia National Lab Solar Thermal Test Facility

- ^ National Renewable Energy Laboratory

- ^ Ausra

- ^ Lloyd Energy Storage, see news, Cloncurry Solar Thermal Storage Project

- ^ NREL CSP Technology Workshop, 7 March, 2007

- ^ Forsberg, Charles W., Per F. Peterson, and Haihua Zhao. "High Temperature Liquied Fluoride Salt Closed Brayton Cycle Solar Power Towers." Journal of Solar Energy Engineering 129 (2007): 141. 28 May 2008.

- ^ Zalba, Belen, Jose M. Marin, Luisa F. Cabeza, and Harald Mehling. "Review on Thermal Energy Storage with Phase Change: Materials, Heat Transfer Analysis and Applications." Applied Thermal Engineering 23 (2003): 251-283. 26 May 2008.

- ^ "Sandia, Stirling to build solar dish engine power plant" (Press release). Sandia National Laboratories. 2004-11-09.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Major New Solar Energy Project Announced By Southern California Edison and Stirling Energy Systems, Inc., press release

- ^ 2x50 MW AndaSol Power Plant Projects in Spain

- ^ Solar Thermal Industry Needs Loan Guarantees

- ^ "Under 10 cents is sort of the magic line"

- ^ Development of Two Solar-thermal Electric Hybridized Power Plant Debuts in Southern California

External links

- www.dlr.de/tt/trans-csp/ Study by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) – How concentrating solar thermal power plants in the Middle East and North Africa could supply Europe with clean power

- Onsite Renewable Technologies at United States Environmental Protection Agency website

- Renewable solar energy websites at Curlie

- Assessment of the World Bank/GEF Strategy for the Market Development of Concentrating Solar Thermal Power

- Concentrating Solar Power An overview of the technology by Gerry Wolff, coordinator of TREC-UK

- NREL Concentrating Solar Power Program Site

- Comprehensive review of parabolic trough technology and markets

- Solar Heat & Power CLFR Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector CSP Concentrating Solar Power

- Solar Thermal Breakthroughs Mean Power Plant Development

- Heat my Home - Latest solar technology reviews and information

- CSP as Scalable Energy Alternative

- Nevada Gets First U.S. Solar Thermal Plant

- Solar thermal energy provider in Ireland.

- SK Energy

- Sopogy

- Solar Millenium (world wide leader for building solar thermal plants - andasol-projects