Y-chromosomal Aaron

Y-chromosomal Aaron is the name given to the hypothesised most recent common ancestor of many of the patrilineal Jewish priestly caste known as Kohanim (singular "Kohen", "Cohen", or Kohane). In the Hebrew Bible this ancestor is identified as Aaron, the brother of Moses.

Research published in 1997 and thereafter has indicated that a large proportion of contemporary Jewish Kohanim share a set of Y chromosomal genetic markers, known as the Cohen Modal Haplotype, which may well derive from this single common ancestor.

Background

Although membership in the Jewish community has, since the second century CE, been passed maternally (see: Who is a Jew?), membership in the group that originally comprised the Jewish priesthood ("Kohens" or Kohanim), is patrilineal, and modern Kohens claim descent from Aaron, brother of Moses.

For human beings the normal number of chromosomes is 46, of which 23 are inherited from each parent. Two chromosomes, the X chromosome and Y chromosome, determine gender. Women have two X chromosomes, one inherited from their mother, and one inherited from their father. Men have an X chromosome inherited from their mother, and a Y chromosome inherited from their father.

Males who share a common patrilineal ancestor should also share a Y chromosome, diverging only with respect to accumulated mutations. Since Y-chromosomes are passed from father to son, all Kohanim men should theoretically have almost identical Y chromosomes; this can be tested with a genealogical DNA test. As the rate that mutations accumulate on the Y chromosome is relatively constant, scientists can estimate the elapsed time since two men had a common ancestor. (See molecular clock.)

Initial studies

The Cohen hypothesis was first tested by Prof. Karl Skorecki and collaborators from Haifa, Israel, in 1997. In their study, "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests," published in the journal Nature,[1] they found that the Kohanim appeared to share a different probability distribution compared to the rest of the Jewish population for the two Y-chromosome markers they tested (YAP and DYS 19); and that furthermore the probabilities appeared to be shared by both Sephardi and Ashkenazi Cohens, pointing to a common Cohen population origin before the Jewish diaspora at the time of the Roman empire.

A subsequent study the next year (Thomas MG et al, 1998)[2] increased the number of Y-STR markers tested to six, as well as testing more SNP markers. Again, they found that a clear difference was observable between the Cohanim population and the general Jewish population, with many of the Cohen STR results clustered around a single pattern they named the Cohen Modal Haplotype:

xDE[1] xDE,PR[2] Hg J[3] CMH.1[2] CMH[2] CMH.1/HgJ CMH/HgJ Ashkenazi Cohanim (AC): 98.5% 96% 87% 69% 45% 79% 52% Sephardi Cohanim (SC): 100% 88% 75% 61% 56% 81% 75% Ashkenazi Israelites (AI): 82% 62% 37% 15% 13% 40% 35% Sephardi Israelites (SI): 85% 63% 37% 14% 10% 38% 27%

Here, becoming increasingly specific, xDE is the proportion who were not in Haplogroups D or E (from the original paper); xDE,PR is the proportion who were not in haplogroups D, E, P, Q or R; Hg J is the proportion who were in Haplogroup J (from the slightly larger panel studied by Behar et al (2003)[3]); CMH.1 means "within one marker of the CMH-6"; and CMH is the proportion with a 6/6 match. The final two columns show the conditional proportions for CMH.1 and CMH, given membership of Haplogroup J.

The data shows that the Cohanim were more than twice as likely to belong to Haplogroup J than the average non-Cohen Jew; and of those who did belong to Haplogroup J, the Cohanim were more than twice as likely to have an STR pattern close to the CMH-6, suggesting a much more recent common ancestry for most of them compared to an average non-Cohen Jew of Haplogroup J.

Thomas et al dated the origin of the shared DNA to approximately 3,000 years ago (with variance arising from different generation lengths). The techniques used to find Y-chromosomal Aaron were first popularized in relation to the search for the patrilineal ancestor of all contemporary living humans, Y-chromosomal Adam.

Responses

The finding led to excitement in religious circles, with some seeing it as providing some "proof" of the historical veracity of the Bible[4] or other religious convictions,[5] but there was also criticism that the paper's evidence was being overstated.[6]

The most basic difficulty with Y-chromosomal Aaron being identified with J1 CMH is that it implies Abraham and the Semitic tribes originated from the Levant or Mesopotamia and not Southern Arabia/Ethiopia, where tradition, both written and oral, indicates their origin. Archaeologists have mapped ancient Semitic tribes to modern Ethiopia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and regions of Saudi Arabia bordering these countries. The only exception to these were the tribes of Aram (Aram-Damascus), Asshur, and Elam as small cluster groups in Mesopotamia overshadowed by Assyria and Babylon (both listed as Hamitic; see Beresh't[Genesis] 10). This suggests a Southern Arabian/Ethiopian origin for the Semites and Abraham, which does not correspond to the evolution of haplogroup J in the Levant.[7]

The biblical tradition of Abraham's origin suggests that he migrated northward from "Ur of the Chaldeans" located in Southern Arabia, with his father Terah, and settled for a time in Haran, located in the Northern Levant (cf. Beresh't[Genesis] 11:31). Biblical tradition also indicates that his extended family also settled in Aram (cf. Beresh't[Genesis] 22:20-4; 28:5; 25:6, 29:1).

The exact location of Ur of the Chaldeans or Ur-Kasdim has been commonly identified with Ur in ancient Sumer (Beresh't[Genesis] 11:27-8).[8] The biblical association of Ur with the Chaldean Empire (consolidated circa 900 BCE) is noteworthy as this connects the biblical tradition of Ur to a specific historical and geographical context during the Chaldean period. The implication is that the naming tradition of "Ur of the Chaldeans" dates to approximately 1300 years or later after the traditional date of Abraham (2200 BCE). It is possible that Ur of the Chaldeans or Ur-Kasdim was located elsewhere in Southern Arabia.

Along these lines, Nebel (2007), et al, found a distinction in J1 (J-p12f2*) haplotypes between Jewish and Arab populations. While a common “early lineage” of J1 (J-p12f2*) was shared between Jewish and Arab populations derived from the Neolithic (ca. 8500 - 4300 BCE) Levant (i.e. Canaanites, etc) they concluded that, “the modal haplotypes of the Muslim Palestinians, the Galilee and the Bedouin, were most likely introduced by more-recent tribal immigrations from the Arabian Peninsula” to their Neolithic (ca. 8500 - 4300 BCE) region of origin.[9] This finding suggests the entry of J1 (J-p12f2*) into the Jewish gene pool was directly from the Levant, before the Byzantine period (324 – 640 CE) and Muslim conquest (633 – 640 CE), while only the haplotypes of the Muslim Palestinians (note distinction between Christian Palestinians)[10], the Galilee and the Bedouin could be attributed to a second wave of migration, in fact, a return to the "Southern Levant and North Africa" from the Arabian Peninsula by "Arab tribal expansions and the Islamic conquest."[11] Thus, the connection between J1 CMH (J-p12f2*) and Y Chromosomal Aaron stands out as a strong contradiction to the biblical tradition of the Southern Arabian origin of the Semitic tribes from which Abraham descended, and an unlikely haplogroup to connect directly with the biblical tradition of the paternal lineage of Y Chromosomal Aaron, and his descendants, the Cohenim of ancient Israel.

A secondary difficulty with the dating of the CMH (which properly can only include J1 CMH) is that the traditional date for Abraham is not known, but often cited as ca. 2200-2000 BCE; Aaron and Moses were exactly 7 generations after Abraham (Exodus 6:14-25). The traditional date for the Conquest of Canaan is 1450 BCE. Moses and Aaron would have lived before the Conquest. Thomas' date of 3000 BP or 1000 BCE falls short of the dates of the same biblical tradition upon which the Cohen tradition was founded.

A third difficulty, is that the Cohen Modal Type at 12 STR markers, does not extend beyond a 2 step genetic distance from the Modal Type, suggesting all J1 Cohenim are descended from a father in the last 1500 years, following current genetic theory, that a one-step YDNA mutation occurs every 500 years (0=500, 1=1000, 2=1500). Thus, those outside of the 2 step-genetic distance from the J1 CMH are highly likely descended from Canaanites or other people groups of the Southern Levant or North Africa, but not with any high degree of probability, descended from the common ancestor of the J1 CMH Cohen families. By analogy the distribution of J1 CMH among Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and Mizrahi Jewish populations may have followed the distribution path of the Siddur, the Jewish prayer book formally compiled several centuries after the destruction of the 2nd Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in the 1st Century CE (70 CE). It is possible that it was distributed and taught by Cohenim, and today, this accounts for the use of the Siddur among all Jewish communities. The earliest existing codification of the Siddur was compiled by Rav Amram Gaon of Sura, Babylon circa 850 CE. Judaism has always welcomed converts and one of the greatest Rabbis in Judaism, arguably the founder of rabbinical Judaism,[12] Rabbi Akiba ben Joseph (ca.50–ca.135 CE), was himself a convert or a son of a convert who by tradition, married into a wealthy and influential Jewish family in ancient Jerusalem.[13] Thus, in objection, evidence of J1 CMH among Sephardic and Ashkenazi populations doees not itself indicate its 2nd Temple period origins, as the Siddur is known to be post-2nd Temple. Nonetheless, it is very possible that the majority of Cohenim today became so through intermarriage with a Cohen family and not random adoption of Cohen status.

A fourth difficulty is that the ancient Israelite ruling class that compiled the biblical text, both royal families and Cohenim, codified the tradition that they were not genetically related to the people groups of Canaan, the various Canaanite tribes, nor the Canaanite-Phoenicians (cf. Beresh't[Genesis] 10:7-19) except through their distant common paternal ancestor, Noah. Dr. Pierre Zalloua and Dr. Spencer Wells, funded by a $1 million dollar grant from National Geographic, identified the haplogroup of the ancient Canaanite-Phoenicians as J2 (M172).[14] While Nebel, et al, identified J1 CMH (J-p12f2*) as Canaanite or another people group originating in the Neolithic Levant (ca. 8500 - 4300 BCE) thousands of years before Abraham was born in Ur of the Chaldeans in Southern Arabia, ca. 2200-2000 BCE. [15] According to the biblical tradition in Beresh't[Genesis] 10, the ancient Israelites descended from Shem, should belong to an entirely different branch of the YDNA phylogenetic tree[16] than Ham. The YDNA phylogenetic tree breaks down into three divisions after the "Eurasian Adam" (M168).[17] M168 had "three sons", M216 (National Geographic labelled as M130), YAP, and M89, which bears remarkable similarity to the tradition of Noah and his three sons, Shem, Japheth and Ham. Applying the work of Dr. Zalloua and Dr. Wells to the biblical tradition, M89 is the likely identifcation of "Ham" as it is under M89 that both J1 CMH (J-p12f2*) associated with the Canaanites, etc., and J2 (M172) associated with the ancient Canaanite-Phoenicians are found. This suggests that the ancient Semitic-Israelites were descended from M216 or YAP; E3b, and its subclades, is the second most common haplogroup among Jewish populations, Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Mizrahi, and is found on the YDNA phylogenetic tree under YAP. Many Cohenim found in E3b bear a genetically distinctive haplotype, such as the E3b1a Cohen family found among the Samaritan peoples, which by tradition, oral and written (biblical), is believed to be of Israelite origin from the Tribe of Levi (see Y-chromosomal Levi below for more on the Samaritans.[18]). Haplogroup E and its subclade, E3b1a (M78), originated in East Africa; E3b1a(M78) is also found in Southern Arabia.[19] E3b1a Cohenim, Levites, and Israelites are found among all Jewish populations. Genetic distinctiveness is the basis for all Cohenim haplotypes, including J1 CMH. Nevertheless, in this light, J1 CMH is the most likely candidate for a clearly defined ancient Canaanite-Israelite modal haplotype, while J2 Cohen haplotypes may represent Canaanite-Phoenician admixture into the Israelite population, as was already noted in the ancient biblical tradition in regards to the building of the First Temple of Solomon (cf. 1 Melachim[Kings] 7:13-14).

If Y Chromosomal Aaron is found in J1 CMH, then the only alternative interpretation is that the ancient Semitic-Israelites that authored the biblical text were, in fact, merely Canaanites who descended from the Neolithic inhabitants of the Levant, these being the people groups generally identified with haplogroups J1 and J2, and that the Israelite ruling class authored a false tradition to justify the Israelite Monarchy. The implication for the biblical tradition, which is the foundation for the faith of billions of people[20] in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, is devastating as it then contains no historical basis for the origins of the Jewish people and the Aaronic Cohenim/priesthood; the indigenous Canaanite origin of the ancient Israelites is a view currently accepted by many archaeologists.[21] In contrast, archaeologist Amihai Mazar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem holds the view that there was a "nuclear group" of Semitic-Israelites of non-Canaanite origin, who formed the “Israelite confederation...which initiated Yahwism and was responsible for the traditions concerning slavery in Egypt, the Exodus, Mount Sinai, and the role of Moses.”[22] If so, the descendants of the original Semitic-Israelite tribal leadership are more likely to be found in a haplogroup other than J1 or J2, both of which evolved in the Levant.

Cohens in other haplogroups

Behar's 2003 data[3] points to the following Haplogroup distribution for Ashkenazi Cohens (AC) and Sephardic Cohens (SC) as a whole:

Hg: E3b G2c H I1b J K2 Q R1a1 R1b Total AC 3 0 1 0 67 2 0 1 2 76 4% 1½% 88% 2½% 1½% 2½% 100% SC 3 1 0 1 52 2 2 3 4 68 4½% 1½% 1½% 76% 3% 3% 4½% 6% 100%

The detailed breakdown by 6-marker haplotype (the paper's online-only table B) suggests that some at least even of these groups (eg E3b, R1b) contain more than one distinct Cohen lineage. It is possible that still further other lineages may also exist, but were not captured in the sample.

Does a CMH prove Cohen ancestry?

One source of early confusion was a widespread popular notion that only Cohens or only Jews could have the Cohen Modal Haplotype. It is now clear that this is not the case. The Cohen Modal Haplotype, whilst notably frequent amongst Cohens, is also far from unusual in the general populations of haplogroups J1 and J2 with no particular link to the Cohen ancestry. These haplogroups occur widely throughout the Middle East and beyond [23],[24]. So whilst many Cohens have haplotypes close to the CMH, a far larger number of such haplotypes worldwide belong to people with no likely Cohen connection at all.

Statistically the value of matching the CMH can be assessed using Bayes' theorem, which in its odds form can be written:

In words, this says that the odds in favour of Cohen ancestry C (ie the probability of having Cohen ancestry, divided by the probability of not having Cohen ancestry), having observed some piece of data D, is given by the odds one would assign given only one's initial information I, multiplied by the probability of having observed D if C is true, divided by the probability of having observed D if C is false.

(In fact, for convenience we shall work with the reciprocal of this equation, ie work in terms of odds against, rather than odds on).

The proportion of the whole male Jewish population that has Cohen ancestry has been estimated at 5%[1]. So if we take that 5% as our initial estimate of the probability of shared Cohen ancestry, then on the basis of the data above:

- Not belonging to haplogroups D or E improves the odds for a Sephardi Jew from 19/1 against to (19/1)*(0.85/1.00) = 16.2/1 against (a 5.8% probability)

- Not belonging to haplogroups D,E,P,Q or R takes the odds to (19/1)*(0.63/0.88) = 13.6/1 against (6.8% probability).

- Membership of Haplogroup J improves the odds to (19/1)*(0.37/0.75) = 9.4/1 against (9.6% probability).

- Being within the CMH.1 group takes the odds to (19/1)*(0.14/0.61) = 4.4/1 against (18.7% probability).

- A full 6/6 match takes the odds to (19/1)*(0.10/0.56) = 3.4/1. (22.7% probability).

Even a full 6/6 match for the 6 marker CMH thus cannot "prove" Cohen ancestry. It can only somewhat strengthen a previously existing belief. But for populations where the background probability assessment of shared Cohen ancestry must be vanishingly low, such as almost all non-Jews, even a full 6/6 match makes only a small difference. For individuals in such populations the CMH likely indicates Haplogroup J, but a completely different ancestry to the Cohanim.

Higher resolution

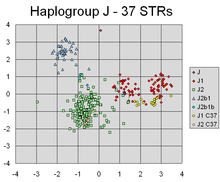

With only six Y-STRs, it is not possible to resolve the different subgroups of Hg J.

With 37 Y-STR markers, clearly distinct STR clusters can be resolved, matching the distinct J1, J2 and J2b subgroups. The haplotypes often associated with Cohen lineages in each group are highlighted as J1 C37 and J2 C37 respectively.

The discussion above applies to the so far published scientific papers. However, in principle some more resolution could be obtained by determining the Cohen haplogroup more narrowly, and/or testing more Y-STR markers to determine whether there is an extended characteristic Cohen haplotype

Haplogroup placement

The largest population of Kohanim which most closely match the Cohen haplotype cluster are believed to belong to subgroup J1 of haplogroup J.[25][26] [27]

Individuals with the genetic Cohen Modal Haplotype can be found in subgroup J2 as well, and occasionally in more genealogically distant haplogroups too; however these are not closely related to the cluster in Haplogroup J1.

The subdivision of J2 which most closely matches the genetic signature of the J1 Cohens is subclade J2a1b, a large fraction of members of which will also have a 6/6 match for the 6-marker CMH. However, this is an example of haplotype convergence: Basically the haplotype "distribution" within one lineage (Haplogroup) overlaps with the haplotype "distribution" of another lineage - its like overlapping branches from two different trees. The more likely reason for the match is convergence (coincidence) or because sharing a common haplotype in the same lineage (Haplogroup). Convergence: Mutation is a random process and over thousands of years can occur in different lines so that by coincidence different "lines" end up with "matching" haplotypes. This accidental agreement is called convergence of different genetic lines, which it is believed have been not been closely related for at least the last 10,000 years; the group in J2a1b who have the 6-marker CMH are devoid of any Cohen traditions in their families.[28]

On the other hand, there are families in Haplogroup J2 who do have a Cohen religious tradition and are proud of it (as there are in several other haplogroups, including Haplogroup R1b). The haplotypes of these Haplotype J2 Kohanim cluster in a unique, small offshoot of J2a1*, close to haplotypes of the J2a1k clade, not the J2a1b clade.[28] These J2 Kohanim typically have a 4/6 match for the 6-marker CMH (with DYS19=15 rather than 14, and DYS388=15 rather than 16). The J1 and the J2 Kohanim may be both descended from unbroken lines of priests going back to the time of Ezra or even earlier. The J2 Cohens do not match the 12-marker J1-extended CMH. The important difference is the two SNP mutations, M172 and M267. These mutations are believed to be at least 10-15,000 years old; but they are equal co-inheritors of a patrilineal tradition which appears to date back well before the Diaspora.

As it happens, three of the four markers for which they do match the CMH-6 were the markers tested by Malaspina et al (2001)[29]. This appears to explain the finding of that paper that "typing a limited number of Italian Cohanim (A. Novelletto unpublished obs.) for the STRs used here, we determined that the Cohen Modal Haplotype ('an important component in the sharing of Ashkenazic and Sephardic Israelite Y chromosomes', Thomas et al. 2000) does indeed belong to network 1.2" (ie the population having DYS413a,b<=18, which is the signature of the J2a1 subclades).

More detailed Cohen haplotypes

In the table below, the first line gives the original 6 marker Cohen Modal Haplotype (CMH-6), which was the basis for the original published papers. The second gives an extended 12 marker haplotype (CMH-12) informally released by the private company FTDNA, based on further work by much of the same research team. It has not yet been peer group reviewed by other scientists or published in the open technical literature.

The next sequence of rows identify other 6-marker haplotypes in haplogroup J found to occur more than once in the sample of 145 Cohanim tested in Behar et al (2003)[3] (table B (web-only) in that paper). Probable extensions of these haplotypes to 12 markers are shown, where it has been possible to find corresponding clusters of Cohen-type names in publicly accessible DNA databases, together with the apparent sub-clade of haplogroup J. This is more possible for the apparently Ashkenazi clusters than for Sephardis, who are much less strongly represented in the databases.

Hg Clade or cluster[30] DYS

393DYS

390DYS

19DYS

391DYS

385aDYS

385bDYS

426DYS

388DYS

439DYS

389iDYS

392DYS

389iiAC[3] SC[3] Some DNA

matchesCMH-6 12 23 14 10 16 11 J1 CMH-12 12 23 14 10 13 15 11 16 12 13 11 30 47% 52% 8EZ7F J2 J2a1* 12 23 15 10 14 17 11 16 12 14 11 30 13% 0 XWPTP J2 J2b 12 24 15 10 15 17 11 15 12 12 11 29 11% 0 F6FSU J2 J2a1* "pre-k" 12 23 15 10 14 17 11 15 12 13 11 29 5% 0 645CH J2 J2a1k 12 24 15 9 16 13 11 29 0 6% J1 J1 "388=13" 12 23 14 10 13 11 0 6% J1 modal 12 23 14 10 13 15 11 16 11 13 11 30 J2 modal 12 23 14 10 13 15 11 15 11 13 11 30 J2 J2a1b 12 23 14 10 13 17 11 16 11 13 11 30

Finally, for comparison, the 12-marker modal haplotypes for the haplogroups J1 and J2 are also shown. It is apparent that in both cases, their haplotype clusters are also centred very close to the Cohen modal haplotype. However, because of the much greater time that has elapsed since the mutations occurred that define the haplogroups, there has been much more time for Y-STR mutations to build up; so, although they have almost the same centre as the Cohen cluster, the J1 and J2 haplotype clusters are much more diffusely spread out. Thus although the CMH-6 is also very near to the most probable haplotype for both J1 and J2, its occurrence frequency is only about 1 to 8% amongst arbitrary members of haplogroup J with no particular Cohen connection.[citation needed]

Other carriers of the DNA

Following the discovery of the very high prevalence of 6/6 CMH matches amongst Cohens, others were quick to look for it, and often to see it as a signpost for possible Jewish ancestry.

News of 6/6 matches in the Lemba of Southern Africa were seen as confirming a possible Jewish lineage (Thomas MG et al 2000);[31] possible links were discussed between the Jews and the Kurds;[32] and some suggested that 4/4 matches in non-Jewish Italians might be a genetic inheritance from Jewish slaves, deported by Emperor Titus in large numbers after the fall of the Temple in AD 70, some of whom were put to work building the Colosseum in Rome.

Such speculation was to some extent tempered when it was realised that Haplogroups J1 and J2 represented at least two different lineages which could be associated with the CMH, (the Italians mostly belong to Haplogroup J2); and that individuals with at least 5/6 matches for the original 6 marker Cohen Modal Haplotype occur widely across the Middle East, with significant frequencies in various Arab populations mainly with J1 Haplogroup, "that are not traditionally considered admixed with mainstream Jewish populations" -- notably Yemen (34.2%), Oman (22.8%), Negev (21.9%), and Iraq (19.2%); and amongst Muslim Kurds (22.1%), Bedouins (21.9%), and Armenians (12.7%).[33]

On the other hand, Jewish populations were found to have a "markedly higher" proportion of full 6/6 matches, according to the same (2005) meta-analysis,[33] compared to these non-Jewish populations, where "individuals matching at only 5/6 markers are most commonly observed".[33]

The authors nevertheless warn however that "using the current CMH definition to a infer relation of individuals or groups to the Cohen or ancient Hebrew populations would produce many false-positive results," and note that "it is possible that the originally defined CMH represents a slight permutation of a more general Middle Eastern type that was established early on in the population prior to the divergence of haplogroup J. Under such conditions, parallel convergence in divergent clades to the same STR haplotype would be possible."[33]

Y-DNA patterns from around the Gulf of Oman were analysed in more detail by Cadenas et al in 2007.[34] The detailed data confirms that the main cluster of haplogroup J1 haplotypes from the Yemen appears to be some genetic distance different from the CMH-12 pattern typical of Eastern European Ashkenazi Cohens.

Y-chromosomal Levi?

A similar investigation was made with men who consider themselves Levites. Whereas the priestly Kohanim are considered descendants of Aaron, who in turn was a descendant of Levi, son of Jacob, the Levites (a lower rank of the Temple) are considered descendants of Levi through other lineages. Levites should also therefore share common Y-chromosomal DNA.

The investigation of Levites found high frequencies of multiple distinct markers, suggestive of multiple origins for the majority of non-Aaronid Levite families. One marker, however, present in more than 50% of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish Levites points to a common male ancestor or very few male ancestors within the last 2000 years for many Levites of the Ashkenazi community. This common ancestor belonged to the haplogroup R1a1 which is typical of Eastern Europeans, rather than the haplogroup J of the Cohen modal haplotype, and most likely lived at the time of the Ashkenazi settlement in Eastern Europe. [3][35][36].

The E3b1 haplogroup has been observed in all Jewish groups world wide. It is considered to be the second most prevalent haplogroup among the Jewish population. According to one major paper [37] it has also been observed in moderate numbers among individuals from Ashkenazi, Sephardic and Samaritan backgrounds that contain the E3b1 haplogroup, having a tradition of descending from the tribe of Levi, suggesting that the E3b1 Levites may have existed in Israel before the Diaspora of 70 C.E.

The Samaritan community is a small, isolated, and highly endogamous group today numbering some 650 members who have maintained extensive genealogical records for the past 13–15 generations. Since the Samaritans maintain extensive and detailed genealogical records, it is possible to construct accurate pedigrees and specific maternal and paternal lineages. The Samaritan community in the Middle East survives as a distinct religious and cultural sect and constitutes one of the oldest and smallest ethnic minorities in the world. Y-Chromosome studies have shown that the majority of Samaritans belong to haplogroups J1 and J2 while the Samaritan Cohanim belong to haplogroup E3b1a.[38]. In 1623-1624 the last member of the high-priestly family, which claimed descent from the eldest son of Aaron, died. The office was then given to the junior branch, descended from Uzziel, the son of Kohath. Since that date the priest has called himself "ha-kohen ha-Lewi," (Heb. "The Levite Priest") instead of "ha-kohen ha-gadol" (Heb. "The High Priest") as in previous times. The approximately 650 individuals comprising the total group of present day Samaritans trace their ancestry over a period of more than 2,000 years to the Biblical Israelite tribes of Ephraim, Menashe and Levi. As a religious sect, the Samaritans broke away from the main stream of Judaism around the fifth century B.C.E.

The biblical tradition of the origin of the Cohen family among the Samaritans is found in 2 Kings 17:27-28 where it indicates that only one Israelite Cohen was sent back from exile in Assyria, circa 722 BCE, by the King of Assyria to teach those living in the Northern Kingdom of Israel (Samaria); this suggests a strong association of haplogroup E3b1a with the biblical Cohenim who authored and compiled the biblical text of the Book of Kings. Those non-Israelites relocated to the region around Samaria by the Assyrians in the same period that the Northern Tribes were exiled to Assyria, later appointed other non-Israelite Cohenim from their own people who were performing non-Israelite authorized priestly functions as observed by the biblical, priestly author at the time of the composition of the Book of Second Kings (cf. 2 Kings 17:32-34); this may be an origin for some among the J1 and J2 Cohenim haplotypes observed among Jewish populations today.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Skorecki, K (1997). "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests". Nature. 385: 32. PMID 8985243.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Thomas, MG (1998). "Origins of Old Testament priests" (PDF). Nature. 394: 138–40. PMID 9671297.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Behar, DM (2003). "Multiple Origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y Chromosome Evidence for Both Near Eastern and European Ancestries". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73: 768–779. PMID 13680527.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kleiman, Rabbi Yaakov (2000). "The Cohanim/DNA connection".

- ^ Clark, David (2002). "Cohanim Modal Haplotype (CMH) finds the Ten Lost Tribes! (among Iraqi Kurds, Hungarians, and Armenians)".

- ^ Zoossmann-Diskin, Avshalom (2001). "Are today's Jewish priests descended from the old ones?". Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 51 (2–3): 156–162. (Summary)

- ^ Yohanan Aharoni, et al, The Macmillan Bible Atlas, Macmillan Publishing: New York, 1993, p. 21.

- ^ Yohanan Aharoni, et al, The Macmillan Bible Atlas, Macmillan Publishing: New York, 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Nebel, et al, “The Genetic History of Populations in the Southern Levant as Revealed by Y Chromosome Polymorphisms,” eds. Marina Faerman, Liora Kolska Horwitz, Tzipi Kahana, Uri Zilberman, in Faces from the Past: Diachonic Patterns in the Biology of Human Populations from the Eastern Mediterranean; Papers in honour of Patricia Smith. BAR International Series 1603: 2007, p. 267.

- ^ Nebel, et al, found the distinction between Muslim Palestinians and Christian Palestinians who were genetically closer to Ashkenazi populations. They stated, "Historically, Christian [Palestinians] are considered to reflect the autochthonous population of the region [Israel-Levant] who did not convert to Islam and resisted admixture with the incoming Muslim populations. Our genetic findings strongly support the above statement." Quoted in: Nebel, et al, “The Genetic History of Populations in the Southern Levant as Revealed by Y Chromosome Polymorphisms,” eds. Marina Faerman, Liora Kolska Horwitz, Tzipi Kahana, Uri Zilberman, in Faces from the Past: Diachonic Patterns in the Biology of Human Populations from the Eastern Mediterranean; Papers in honour of Patricia Smith. BAR International Series 1603: 2007, p. 266.

- ^ Nebel, et al, “The Genetic History of Populations in the Southern Levant as Revealed by Y Chromosome Polymorphisms,” eds. Marina Faerman, Liora Kolska Horwitz, Tzipi Kahana, Uri Zilberman, in Faces from the Past: Diachonic Patterns in the Biology of Human Populations from the Eastern Mediterranean; Papers in honour of Patricia Smith. BAR International Series 1603: 2007, p. 267.

- ^ Yer. SheḲ. iii 47b, R. H. i. 56d.

- ^ http://www.njop.org/html/akiva.html

- ^ http://www.independent.com.mt/news.asp?newsitemid=57215; also see National Geographic Magazine, October 2004 issue, for discussion of the ancient Phoenicians and J2(M172) and its "parent" group of M89. Available online: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/features/world/asia/lebanon/phoenicians-text/1 [accessed: March 10, 2008]

- ^ Nebel, et al, “The Genetic History of Populations in the Southern Levant as Revealed by Y Chromosome Polymorphisms,” eds. Marina Faerman, Liora Kolska Horwitz, Tzipi Kahana, Uri Zilberman, in Faces from the Past: Diachonic Patterns in the Biology of Human Populations from the Eastern Mediterranean; Papers in honour of Patricia Smith. BAR International Series 1603: 2007.

- ^ http://ycc.biosci.arizona.edu/nomenclature_system/fig1.html

- ^ https://www3.nationalgeographic.com/genographic/atlas.html

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y-chromosomal_Aaron#Y-chromosomal_Levi.3F

- ^ Semino, et al, “Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area.” Am J Hum Genet. 2004 May; 74(5).

- ^ http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html

- ^ Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein (Tel Aviv University) is the most outspoken proponent of this position. He wrote, "There is no question that the biblical description of the United Monarchy [of David and Solomon] draws a picture of an idyllic golden age; and that it is wrapped in the theological and ideological goals of the time of the authors...the ideology of late-monarchic Judah...projected into its semi-mythical early history, with the goal of looking at a promising future based on that mythical, glamours past" quoted in I. Finkelstein, "A Low Chronology Update: Archaeology, history and bible". p. 35, in T. Levy and T. Higham (eds.), The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating – Archaeology, Text and Science. Equinox Publishing: London, 2005. The accusation that the ancient Israelites invented their past history, i.e. lied, bears an ominous similarity, although not in content, to Martin Luther's 1543 treatise Von den Jüden und ihren Lügen ("On the Jews and their Lies") which was used by the Nazis to justify anti-Semitism, the persecution of the Jewish people, the burning of Synagogues, and ultimately the Holocaust. Also see I. Finkelstein, “The Archaeology of the United Monarchy: an Alternative View”, Levant 28 (1996):177-187; and I. Finkelstein, “The Great Transformation: The ‘Conquest’ of the Highlands Frontiers and the Rise of the Territorial States”, Pp. 349-365 in: T. Levy (ed.), The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Facts on File: New York, 1995.

- ^ Amihai Mazar, The Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000 – 586 B.C.E, New York: Doubleday, 1992, 355. Also see, A. Mazar, "The Debate over the Chronology of the Iron Age in the Southern Levant: Its history, the current situation and a suggested resolution". Pp. 15-30 in: T. Levy and T. Higham (eds.), The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating – Archaeology, Text and Science. Equinox Publishing: London, 2005.

- ^ Nebel, A (2001). "The Y chromosome pool of Jews as part of the genetic landscape of the Middle East". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69: 1095–1112. PMID 11573163.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Semino, O (2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74: 1023–1034. PMID 15069642.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The private company FTDNA has indicated that the CMH Kohanim cluster is associated with J1 rather than J2. Although as of March 2007 no scientific paper has yet been published disclosing their full data, the conclusion matches a clustering of Cohen-type names close to Ysearch G6839 in very much more limited data from various sources that are publicly accessible.

- ^ The Y-Haplogroup J DNA Project- see Results page for CMH map [1]

- ^ Nebel et al. 2001, Fig 3- CMH network [2]

- ^ a b Schrack, Bonnie (13 April 2007). "Cohen does not equal CMH,CMH does not equal Cohen -- only in J1 do they coincide". GENEALOGY-DNA-L Archives. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ Malaspina, P (2001). "A multistep process for the dispersal of a Y chromosomal lineage in the Mediterranean area". Ann. Hum. Genet. 65 (Pt 4, July): 339–49. PMID 11592923.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nomenclature and analogues from Schrack, B. "The Y-Haplogroup J DNA Project". FTDNA.com. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas, MG (2000). "Y chromosomes traveling south: the Cohen modal haplotype and the origins of the Lemba--the "Black Jews of Southern Africa"". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66: 674–86. PMID 10677325.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brook, Kevin Alan, The Genetic Bonds between Kurds and Jews, Netewe, January 19, 2002.

- ^ a b c d Ekins, JE (2005). "An Updated World-Wide Characterization of the Cohen Modal Haplotype" (PDF). ASHG meeting October 2005.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); line feed character in|coauthors=at position 141 (help) - ^ Cadenas, AM (2008). "Y-chromosome diversity characterizes the Gulf of Oman". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16: 374–386. PMID 17928816 DOI 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201934.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Behar, DM (2004). "Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome variation in Ashkenazi Jewish and host non-Jewish European populations" (PDF). Hum. Genet. 114: 354–365. PMID 14740294.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nebel, A (2004). "Y chromosome evidence for a founder effect in Ashkenazi Jews". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (3): 388–91. PMID 15523495.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.familytreedna.com/pdf/Behar_contrasting.pdf.

- ^ Shen, P (2004). "Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations From Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation" (PDF). Human Mutation. 24: 248–260. PMID 15300852.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)