Old South Arab religion

The Old South Arabian religion was like the other religions of Semitic peoples polytheistic , until the 4th century AD, the spread Judaism and Christianity in South Arabia from before the beginning of the 7th century by Islam were displaced.

Polytheistic time

Pantheon

Like all other ancient oriental religions (except Judaism ), the ancient South Arabic religion was polytheistic, whereby the astral character of the gods is clearly recognizable. Most deities are usually attempted to be traced back to a triad of sun, moon and Venus, the most extreme of which is Ditlef Nielsen . Nielsen's reconstruction of a three deities Gods family has long been widely rejected, but the simplification of the gods is in terms achieved in a triad no consensus: especially Maria Höfner trying to read rare deities as manifestations of the three triad figures, while z. B. AFL Beeston thought this was too simplistic.

At the head of the pantheon was the god Athtar , the representative of the planet Venus , in all the ancient South Arabian empires . He was also responsible for the vital irrigation as well as a warlike god who brought death to the enemy. In Qataban and Hadramaut, the sun was undisputedly represented by shams , in addition to which, especially in the other realms, there were several goddesses who can also be interpreted with great certainty as sun deities. In addition, each empire had its own national god , in Saba this was Almaqah , who is traditionally regarded as the moon god, but he was also associated with the sun due to his symbols. The Minean and probably Ausanian national god was called Wadd ("love"); he is expressly referred to as the moon god. Maybe he came from northern Arabia. Sin ("moon"), the hadramitic national god, is traditionally regarded as a moon god because of his name, but because of his symbolism he could also have been a sun god. After all, the national god was Qataban's amm , perhaps also a moon god.

In addition to these important deities, the inscriptions mention many other, mostly regionally narrowly limited gods, including Sama , who was worshiped in western Saba and was later ousted by Ta'lab , the goddess ' Uzzayan, borrowed from northern Arabia, and Dhu-Samawi , the tribal god of the between Ma'in and Najran resident Amir .

Nothing is known about mythology, only the symbols assigned to various gods allow conclusions to be drawn about the mythological position of individual gods, but hardly any symbols and symbolic animals can be reliably assigned to a deity.

Cults

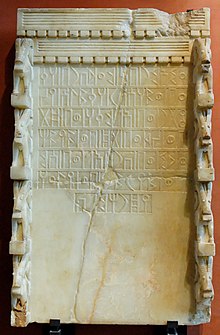

The residence and place of worship of a deity was their temple, an open building ( haram or mahram ), access to which was only permitted under certain ritual purity laws. For example, it was forbidden to enter the temple with dirty or torn clothes, and women were forbidden to visit it during menstruation. In addition to the rich public temples, there were also smaller sanctuaries, the “castle chapels”, in which the patron ( shāyim ) of the lord's family was venerated, as well as house shrines ( mas 3 wad “fireplace”) and prayer areas ( madhqanat ). While the places of worship mentioned were all within the settlements, steles ( qayf ) stood isolated in the landscape at prominent points .

Much less is known about the cult acts themselves. The most important act of this kind was the sacrifice performed on various types of altars, distinguishing between sacrifices, incenses and possibly libations . Up to 40 animals could be sacrificed on official occasions; Various wild cats and bulls are mentioned as sacrificial animals . An act similar to the sacrifice was the sacred hunt, which was practiced exclusively by the ruler. The prey apparently coincides with the sacrificial animals of the sacrifice. In certain parts of the Hadramaut this rite is still practiced today. It is not certain whether there was also human sacrifice , so far only the ritual killing of enemies in connection with fighting has been handed down. The personal endications documented in the early days are only to be understood as an obligation of a person to work in the temple of a deity. Another important cultic act was the oracle ( masʾal ), which was apparently practiced in certain places, for example the temple of Ta'lab in Riyam on the Jebel Itwa was known as an oracle site in Islamic times . Inscriptions from an oracle site near Naschq im Jauf even make it possible to reconstruct the ritual: the questioning took place on specified days, the questioner made sacrifices on certain altars or donated a statuette and then presented his question. The oracle was conveyed to him by a priest, if the answer was negative, the questioner made another sacrifice and repeated the questioning. In addition, the Los oracle ( maqsam ) and the oracle transmission are documented as a vision in sleep in the temple.

Other cults have only survived in fragments, such as the circulation around a sanctuary ( tawāf / ṭwf ), the introduction of a woman to a god as wife, petition processions to the temple, ritual cleaning of weapons and the public confession of guilt, especially that of a violation of purity regulations. In the "Mukarrib period" the union took place, about the expiry of which nothing is known.

The temples were organized by various priests and other title holders, but their exact function remains obscure. Of great importance were some priests who changed in certain cycles, the Kabīre , and were therefore used as eponyms for dating the year. It is unclear whether the Mukarribe were also priests, after all the Qataban Mukarribe had priestly titles.

Cult of the dead

The graves had various shapes in pre-Islamic southern Arabia. Artificial grave caves (area: approx. 3 x 3 m, height: 3 m) with niches in the inner walls, which were probably intended for grave goods or small statuettes, were carved into the rock walls. Another, simpler form of burial consisted of holes dug in the ground, in which the corpse was placed, and which were covered with a pile of stones and possibly marked with a stone circle or the like. Above-ground graves were reserved for more distinguished people. A common type of these grave structures were mausoleums-like, cube-shaped systems with chambers inside, in the walls of which there were niches for the reception of the dead. A particularly large building, which is located next to the Awwam in Marib, contained around 60 burial niches and additional burial chambers under the floor. Another type of above-ground grave structures were the so-called pillboxes , which were apparently built exclusively on mountain ridges. Their outer walls were mostly round, through an entrance one got into the square interior, which was covered by a vault covered with rubble. There are also evidence of round grave houses and towers that look like a beehive in elevation. All of these grave types can occur individually as well as in groups of different sizes. In the vicinity of many graves there were grave steles, which often name the person buried and sometimes represent him both in this world and in the afterlife together with a deity.

Very little is known about ancient South Arabian ideas of the afterlife, as no actual religious texts have survived. An indication of such notions are above all the grave goods, unfortunately often looted, which included jewelry, seals, amulets, sculptures, weapons and ceramics as well as - so far only documented once - slaughtered animals. As in other cultures, they probably served to care for the dead in the afterlife. The express ban on burying other people in graves that have already been occupied points in this direction. In some cases, the dead were also mummified .

monotheism

Main article: Rahmanism

Main article: History of Judaism in Yemen

Since the 2nd half of the 4th century AD, the old gods are no longer invoked in the inscriptions of the Sabao-Himjar Empire, but the “Lord of Heaven” and “the Merciful”. This religion is also known as “Rahmanism” after the old South Arabic word Rahmanan “the merciful”. The existence of synagogues and some inscriptions show that Judaism played an important role in Himjar from the 4th century, but it is not certain that it was the only monotheistic religion in southern Arabia. Since the beginning of the 6th century at the latest, Christian communities have also been known who also called their God Rahmanan . Yusuf Asʾar Yathʾar († 525) was the only king in southern Arabia whose monotheism was demonstrably Jewish, perhaps as a counterweight to the Christian competitor Aksum, who introduced Christianity in 525 with the conquest of Yemen, which was ruling until the introduction of Islam in 632.

Individual evidence

- ↑ in: D. Nielsen (Ed.): Handbuch der Altarabischen Altertumskunde , Volume 1. Copenhagen 1927, p. 227

- ↑ Gese / Höfner / Rudolph: The religions of Old Syria, Altarabia and the Mandaeans , see bibliography

- ↑ G. Garbini: Il deo sabeo Almaqah , in: RSO 48 (1974), pp. 15-22; also Jacques Ryckmans (see bibliography)

- ↑ Adolf Grohmann: symbols of gods and symbolic animals on South Arabian monuments (memoranda of the Academy of Sciences Vienna, philosophical-historical class, volume 58, treatise 1) Vienna 1914 and p. 295-317 in Gese, Höfner, Rudolph: The religions of Old Syria , Altarabia and the Mandaeans (see bibliography)

- ↑ See: G. Ryckmans: La confession publique des péchés en Arabie Méridionale préisplamique , in: Le Muséon, No. 58, 1945, pp. 1-14

- ↑ M. Maraqten: Types of Old South Arabian Altars , in: Norbert Nebes (Ed.): Arabia Felix. Contributions to the language and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. Festschrift Walter W. Müller for his 60th birthday. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1994. ISBN 3-447-03603-6 , pp. 160-177

- ↑ On this: AFL Beeston : The Ritual Hunt , in: Le Muséon, No. 61, 1948, p. 183 ff .; Walter W. Müller, in: O. Kaiser (Ed.): Texts from the environment of the Old Testament , Volume 2, Delivery 3 , p. 442 ff.

- ↑ Ryckmans, Religion of South Arabia (see bibliography) p. 174

- ↑ These are the inscriptions CIH 460–466, for their content see: AFL Beeston: The Oracle Sanctuary of Jār al-Labbā , in: Le Muséon, No. 62, 1949, pp. 209 ff.

- ↑ For details see Gese / Höfner / Rudolf (see bibliography), pp. 348–350

- ↑ On the Sabaean eponym system: AG Lundin: Die Eponymliste von Saba (from the Halil tribe) , Vienna 1965; Ch. J. Robin: À propos d'une nouvelle inscription du règne de Shalrum Awtar, un réexamen de l'éponymat sabéen à l'époque des rois de Saba 'et de dhû-Raydan . In: Norbert Nebes (ed.): Arabia Felix. Contributions to the language and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. Festschrift Walter W. Müller for his 60th birthday. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1994. ISBN 3-447-03603-6 , pp. 230-249

literature

- Hartmut Gese, Maria Höfner , Kurt Rudolph: The religions of Old Syria, Altarabia and the Mandaeans (= The religions of mankind . Volume 10,2) Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne / Mainz 1970 (South Arabia: pp. 234–353. Very extensive and detailed, but partially outdated overall presentation)

- Christian Robin: Himyar et Israël. In: Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres (ed.): Comptes-rendus des séances de l'année 2004. 148/2, 2004, pages 831–901 (on Judaism in South Arabia)

- Jacques Ryckmans: The Old South Arab Religion. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen , Pinguin-Verlag, Innsbruck / Umschau-Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1987, pp. 111-115, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5

- Jacques Ryckmans: Religion of South Arabia. In: DN Freedman (Ed.): The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Volume VI. New York 1992, pp. 171–176, ISBN 0-385-26190-X (extensive bibliography in the appendix)

- Walter W. Müller: Art. Himyar . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 15 (1991) 303–331, ISBN 3-7772-5006-6 (extensive presentation of South Arabian Christianity)