Work person

By working person is referred to in the work studies the person holding a work performing. The terms worker , worker , etc. are also used synonymously or the designation of the activity such as B. lathe operators , cutting machine operators , machine operators , office workers or specialists .

General

The previous designation worker was dropped, as the worker should include anyone entrusted with a specific activity and the term worker is sometimes understood to be very limited and politically charged. According to most definitions, a marching soldier is not a worker, but according to this understanding it is a worker.

The term work person is used both descriptively and prescriptively in work studies. In the work analysis, the worker is examined for knowledge and skills that are necessary to perform the task. In the work design , the work person is described who is required to carry out the work task.

Evaluation of activities

For the activities of a worker, evaluation criteria are used as part of the job evaluation.

For a long time, the factors defined by Rohmert were used for this :

- Feasibility (short term): Feasibility describes the physical possibility of performing an activity. After this, no order may be given to paint the ceiling if the physical necessities (ladder, long-handled brushes, etc.) are not available. These categories also include physical impossibilities (running 100 m in 3 seconds)

- Endurance (Long Term): Endurance is a long term assessment. If a worker had to stand at the tapping of a blast furnace for 8 hours, the work would no longer be bearable. But this job can very well be taken for short periods of time.

- Reasonability - Reasonability is a social problem. An activity can be considered unreasonable in one cultural area, but in another it can be the natural income of a worker (shoveling faeces from a tank without protective clothing).

- Satisfaction : Satisfaction takes place on the psychological level of the worker. An activity can be feasible , bearable and reasonable , but it can cause the performer experiences of frustration, which would increasingly restrict his productivity.

According to Rohmert, the evaluation criteria of work activities should be met in ascending order if the respective work performance is to be maximized. Typical work environments, however, often suffer from deficits, the avoidance of which should be pursued by the work organization.

The Rohmert schema has come under criticism because, on the one hand, feasibility should be a self-evident prerequisite for work activity and, above all, because job satisfaction has found widespread use in practice, but the term is scientifically very controversial and at least "not a useful criterion for evaluating Represents work ” .

The scheme by Luczak et al. from the core definition of ergonomics is: damage-free, executable, tolerable and impairment-free working conditions.

Winfried Hacker's system became even more important , as it is divided into executable, harmless, impairment-free and personality- enhancing.

Goal setting

The aim of the exact description of a worker is to look for optimizing a work system. Since the worker is viewed as one of seven system elements, the work organization can be geared to it by influencing the knowledge and skills of the worker.

A runner (athlete) may serve as an example. The resources are running track, shoes and clothing. The training of the runner via the division of a race, optimized training methods up to psychological influencing of one's own psyche or that of the opponent are learnable skills which can give the runner an advantage in competitions. It is understandable that in this example the greatest development potential is to be found in the worker - automation is not a solution for this work system. Similarly, knowledge and skills can be determined for industrial or office workers, drivers, police officers, doctors, etc., the mastery of which improves the performance of the work. Improvements can be sought in increasing speed, reducing the frequency of errors, reducing work-related fatigue or risk of injury, etc.

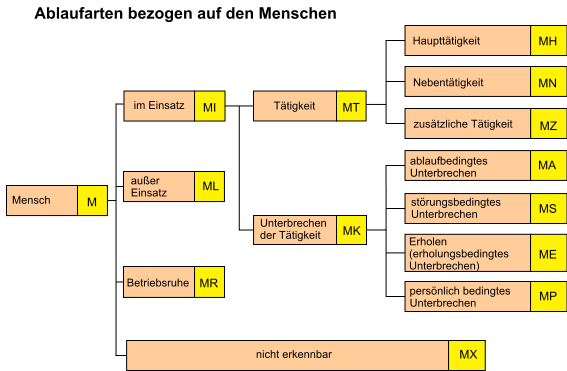

Structure of the types of process

For the analysis of work activities, REFA provides a structure that is used for both observations and work design.

The primary level of structure distinguishes the worker

-

in action

and means that the worker is active in the work system while performing a work task. -

Out of action

means that the worker has interrupted the work due to one of four reasons -

Operating peace

means that the action under a legal, operational or tariff break, a holiday is so broken. -

not recognizable

means that the worker's activity cannot be assigned to any of the three other activities.

The activity is divided into (analogous to usage )

-

Main activity

the worker carries out the work, d. H. in the “assembly” task, the worker assembles, or “welding” task if the worker welds. -

Secondary

job means that the employee does not directly carry out the work task, i.e. H. In the “assembly” task, the worker grabs a screwdriver or material, or “welding” task when the worker checks a weld with a hammer. -

Additional activity

means activities that an employee carries out in addition to main and secondary activities, for example work during the main usage time of a resource.

The interruptions in activity (also analogous to use ) are divided into four possible types of interruption.

-

Process-related interruption

occurs when the work flow in the work system makes an interruption inevitable, e.g. B. when the worker is waiting for an automatic sequence to complete. -

A malfunction -related interruption occurs when the work process is interrupted due to a malfunction (broken drill, dirty tool, etc.). This also includes disruptions caused by the supervisor asking a question. -

A recovery-related interruption

occurs when the worker takes a recovery-related break. -

Personal interruption

refers to all other interruptions in work; z. B. going to the toilet, drinking or eating during working hours.

swell

- ↑ REFA (Ed.): Methodology of work studies. Part 2: Data Discovery. Hanser, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-446-12704-6 .

- ↑ REFA (Ed.): Methodology of work studies. Part 1: Basics. Hanser, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-446-14234-7 , p. 99.

- ^ W. Rohmert: Tasks and content of ergonomics. In: The vocational school. 24, 1972, pp. 3-14.

- ↑ Eberhard Ulich: Industrial Psychology. 6th edition. Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-7910-2442-6 , p. 139.

- ↑ H. Luczak, W. Volpert , A. Raeithel, W. Schwier, T. Müller, M. Rötting : Ergonomics: core definition, catalog of objects, research areas. 3. Edition. RKW, Eschborn 1989, ISBN 3-921451-75-2 , p. 59.

- ↑ Winfried Hacker: Industrial Psychology: Psychological regulation of work activities. VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-326-00164-9 , p. 511 f.