Article 38 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

Article 38 of the German Basic Law (GG) is located in the third section of the Basic Law, which contains provisions on the German Bundestag , the parliament and legislative body at the federal level . It describes the legal basis of the Bundestag election and the legal status of the Bundestag member . In Art. 38 GG thus is a key provision of the German constitutional law .

Art. 38 paragraph 1 sentence 1 GG guarantees every citizen the right to vote and to be elected. In jurisprudence, the former is referred to as the active , the latter as the passive right to vote . The choice must be general, free, equal, direct and secret, and it must be understandable and controllable by the public.

Article 38, paragraph 1, sentence 2 of the Basic Law gives the member of parliament a special legal position that entitles him to exercise parliamentary activity free from interference by third parties. Furthermore, he is neither bound by orders nor by instructions when performing his office, but merely subject to his conscience. This is called a free mandate in law.

According to Art. 93 Paragraph 1 Number 4a of the Basic Law, Art. 38 of the Basic Law is a right that is equal to fundamental rights . Therefore, holders of this right can object to the violation of Article 38 of the Basic Law by means of a constitutional complaint before the Federal Constitutional Court . In certain cases, members of the Bundestag also have the option of filing an application in the organ dispute proceedings .

The guarantees of Art. 38 GG can be shortened by conflicting constitutional law. As such, interests under state organization law come into question, such as the functionality of parliament.

Normalization

Art. 38 GG has read as follows since its last amendment on July 31, 1970:

(1) The members of the German Bundestag are elected by general, direct, free, equal and secret ballot. They are representatives of the whole people, not bound by orders and instructions and only subject to their conscience.

(2) Whoever has reached the age of eighteen is entitled to vote; It is possible to choose who has reached the age at which they come of majority.

(3) The details are determined by a federal law.

Art. 38 GG contains different functions. Article 38, paragraph 1, sentence 1 of the Basic Law and Article 38, paragraph 2, of the Basic Law contain several structural provisions and rights equivalent to fundamental rights, some of which are freedom , and some are rights of equality . Article 38, paragraph 1, sentence 2 of the Basic Law establishes fundamental organizational rights for members of the German Bundestag and parliamentary groups. Art. 38 paragraph 3 GG assigns the federal government the right and the task of defining the right to vote in more detail by law.

History of origin

The principle of the free mandate was first codified in the German constitutional tradition in the Prussian constitutions of 1848 and 1850 . Guarantees, which are now contained in Art. 38 GG, were still to be found in the Paulskirche constitution of 1849. However, due to opposition from numerous German states, this did not prevail, so that its guarantees had no legal effect.

The Imperial Constitution of 1871 stipulated that the Reichstag elections were to take place secretly and directly. The MPs were also independent.

The foundations of the electoral system were further elaborated by the Weimar Constitution (WRV) of 1919. According to Art. 22 WRV, the members of the Reichstag were elected by proportional representation, which was general, equal, direct and secret. Art. 21 WRV guaranteed the freedom of parliamentary mandate.

The Parliamentary Council , which developed the Basic Law between 1948 and 1949, wanted to follow the Weimar Constitution with regard to the electoral system and the position of MPs. However, he wanted to avoid the inadequacies of this constitution. To this end, he tried to find an appropriate balance between a regulation that was as free as possible and the necessary framework for effective parliamentary work. The constitutional giver deliberately refrained from further regulations on the electoral system in Article 38 of the Basic Law in order to give the legislature scope for action in this regard. So far, Art. 38 GG has only been changed once: By law of July 31, 1970, the minimum voting age, which was then 21 years, was reduced to 18 years. In this way, the legislature wanted in particular to align the electoral law with compulsory military service , which existed from the age of 18.

Bundestag elections

Article 38, paragraph 1, sentence 1 of the Basic Law regulates the principles of elections to the German Bundestag. On the other hand, the standard contains the fundamental right to participate in the election as voter and candidate. Every German has this right . Pursuant to Article 116, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law, a German is a person who has German citizenship or is equal to the holder of the citizenship. The fact that only Germans are bearers of the same fundamental right is not expressly stipulated in the constitution, but results from the fact that, due to the popular sovereignty guaranteed by Article 20, Paragraph 2, Sentence 1 of the Basic Law, only Germans may participate in the Bundestag election.

Suffrage

According to Article 93, Paragraph 1, Number 4a of the Basic Law, the right to vote represents a right that is equal to fundamental rights. It is an individual right. Therefore, for example, family voting rights would be unconstitutional according to the widespread view in law.

The right to vote is divided into an active and a passive component: The active right to vote describes the right to vote. The right to be elected gives the right to be elected by the voters.

From the right to vote, jurisprudence also derives the guarantee that citizens can decide who exercises state authority in Germany through their choice. This possibility assumes that the Bundestag has a sufficient number of competencies. Therefore, according to the prevailing view in jurisprudence, Article 38 (1) sentence 2 of the Basic Law restricts the transfer of competences from the Bundestag to the European Union : This must not go so far that the Bundestag no longer makes fundamental decisions itself or does not sufficiently influence the relevant decision-making can.

Electoral system

According to Article 38, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law, the Federal Government has extensive, exclusive legislative competence to regulate the right to vote in the Bundestag. This provision also obliges the legislature to shape the electoral system. The Basic Law does not prescribe a specific electoral system, so that the legislature has a wide range of design options in this regard. The Federal Election Act (BWahlG) is an important source of law for the Bundestag elections, which in practice are shaped by political parties .

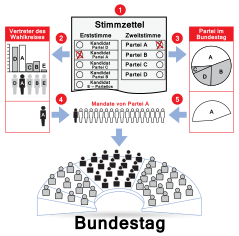

The legislature regulated the Bundestag election as a mixture of majority and proportional representation . This is known as personalized proportional representation . According to Section 1 (2) BWahlG , the German Bundestag is composed of 299 members who are elected directly in constituencies with the first vote. Since the winner is whoever receives the most votes within his constituency, it is a majority vote. A further 299 MPs are elected to the Bundestag by being nominated on a state list as candidates for which the voter casts his second vote . The more votes a list receives, the more candidates it can send to the Bundestag. The seat allocation is calculated using the Sainte-Laguë / Schepers method . According to § 6 Paragraph 3 Clause 1 BWahlG, only the votes for those lists that achieve at least five percent of all votes are considered. This does not apply to parties that obtain a direct mandate in at least three constituencies. If a party, through directly elected candidates in parliament, obtains a higher percentage than it would be entitled to according to the list result, it retains its direct mandates in accordance with Section 6 (5) sentence 1 BWahlG. These are referred to as overhang mandates in law. So that the distribution of seats within the Bundestag corresponds to the percentage distribution of votes in the list results, the number of members in the Bundestag is increased with the help of compensatory mandates as far as is necessary to achieve a corresponding ratio if there are overhang mandates .

Electoral principles

According to Article 38, Paragraph 1, Sentence 1 of the Basic Law, members of the German Bundestag are elected by general, direct, free, equal and secret elections. These requirements are intended to ensure the legitimacy of members of the Bundestag. In terms of the legal system, they are concretizations of the principle of democracy standardized in Art. 20 Paragraph 1, 2 GG , a fundamental state structure principle, the essence of which is not accessible to a constitutional amendment due to Art. 79 Paragraph 3 GG .

For state elections Art indeed true. 38 GG not directly, but it influences on the uniformity clause of Art. 28 1, clause 1 paragraph, the legal situation in the countries. Therefore, their elections must be based on the criteria of Art. 38 Paragraph 1 Sentence 1 GG. Furthermore, the principles of Article 38, Paragraph 1, Clause 1 of the Basic Law, as general legal principles, influence the organization of elections within associations under public law, such as social security and staff representatives . They apply to a limited extent in the context of self-governing institutions , such as universities , as these receive their legitimation at least through their tasks.

Generality

The criterion of the general public requires that all eligible voters have equal access to voting. This guarantee is a special right of equality that supersedes the general principle of equality of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG as a lex specialis .

The generality principle applies to both active and passive voting rights. The general public of elections forbids, for example, making it difficult for certain people or groups to cast their votes. It is also inadmissible to judge whether political parties are allowed to vote on the basis of different criteria.

The principle of universality of choice can be restricted by conflicting constitutional law. A corresponding restriction is contained in Article 38, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law, which links the right to vote to the completion of the age of eighteen. Further restrictions are the incompatibility provisions of the Basic Law, which prohibit an election as a member of parliament. Such a provision exists for the Federal President , for example, in accordance with Article 55 (1) of the Basic Law . Another limitation of the general public of the election is the exclusion from the election by a judicial decision according to § 13 No. 1 BWahlG, which can occur according to § 45 paragraph 5 of the Criminal Code (StGB) as a result of a criminal conviction.

Right away

The criterion of the immediacy of the election requires that the citizen's vote influences the election result without any intermediate steps. This would, for example, be incompatible with the election of representatives by electors , as is the case in the US presidential election . The dormant mandate also violates the principle of immediacy.

Free

The principle of freedom of choice prohibits the citizen's voting decision from being influenced by sovereign coercion. The citizen must therefore be able to form his will freely. It is inadmissible, for example, if a public official, using his official authority, influences the voter in favor of or against a political party. One expression of the freedom of choice is section 108 of the Criminal Code, which makes coercion of the voter a punishable offense.

In jurisprudence it is controversial whether the introduction of compulsory voting for the purpose of the greatest possible voter participation would be compatible with the principle of freedom of choice. According to the prevailing opinion, this is not the case, as failure to attend an election can constitute a political statement worthy of protection. Likewise, the purpose associated with this could easily be circumvented by the voter, for example by casting an invalid vote.

Equal

Equality is guaranteed if every voter can exercise his right to vote in the same way. This guarantee is a special right of equality that supersedes the general principle of equality of Art. 3 Paragraph 1 GG as a lex specialis.

For the active right to vote, the principle of equality means that the electoral process must be designed in such a way that each vote cast has the same weight. On the one hand, this assumes that all votes have the same count value (count equality). On the other hand, each vote must have a comparable influence on the election result (equal success value). With regard to the right to stand as a candidate, the consequence of equality of choice is that every candidate must be given the same chance to be elected. This prohibits, for example, the exclusion of independent applicants from reimbursement of election campaign costs and election advertising with budget funds. Furthermore, the electoral equality obliges the public sector to be neutral in the election campaign.

A constitutional justification cannot be used to intervene in the equality of counts. According to the case law of the Federal Constitutional Court, however, the equality of success value may be restricted by conflicting constitutional law, which has a similar weight to the equality of voting rights.

The court considers the 5% threshold clause in accordance with Section 6 (3) sentence 1 BWahlG to be permissible , as this is suitable for ensuring that the functioning of Parliament is not impaired by too large a number of small parties. However, it judged such clauses to be inadmissible at the municipal and European level, since the bodies elected there differed considerably from the Bundestag.

The negative voting weight represents a violation of the equality of votes . This is a mathematical effect in which the voter's vote could act against his will. For example, due to the electoral law at the time, it was possible that an additional second vote for a party could lead to it losing a mandate. The Federal Constitutional Court declared the relevant regulations to be unconstitutional, since the election result must reflect the will of the voter.

It is controversial in jurisprudence whether the basic mandate clause of § 6 Paragraph 3 Sentence 1 Alternative 2 BWahlG constitutes a violation of equality of choice. According to § 6 Paragraph 3 Clause 1 Alternative 2 BWahlG, all votes for a party that has received less than five percent of all votes are taken into account if it has obtained at least three direct mandates. The Federal Constitutional Court considers this clause to be constitutional, since the number of direct mandates expresses a particular political significance of a party, which is why it is appropriate to take into account their second votes as well. Some voices in legal doctrine oppose this view that the success of a party in several constituencies has little significance for the national political significance of a party.

Secret

An election is secret if it is not clear to a third party for which candidate the voter votes. Restrictions on the secrecy of the choice result in particular from the interest in its functionality.

Public

The criterion of publicity of choice, which is derived from Art. 38 Paragraph 1 Clause 1 and Art. 20 Paragraph 1, 2 of the Basic Law, is also recognized in jurisprudence. This assumes that the voter can follow and check the election process. In a conflict, the principle of choice is public, for example, with the introduction of voting machines . These are permissible if the citizen can control their work processes.

Legal status of the MP

The member of the Bundestag represents the entire German people in accordance with Article 38 (1) sentence 2 of the Basic Law. According to Art. 38 Paragraph 1 Clause 2 of the Basic Law, he is exclusively subject to his conscience and not bound by orders and instructions. Jurisprudence describes this position as a free mandate. This is to ensure that he forms his will in Parliament exclusively on the basis of his own convictions. The mandate of the MP is valid during his legislative period . According to Art. 39, Paragraph 1, Clause 1 of the Basic Law, this begins when the Bundestag meets after the election. It expires when a new one meets.

The legal status of the member of parliament is specified in the Members' Act (AbgG) and the rules of procedure of the German Bundestag (GOBT).

Rights and obligations

Parliamentary participation

So that the MP can effectively exercise the free mandate given to him through his election, he has numerous parliamentary participation rights. These are regulated in detail by the GOBT. Article 38, paragraph 1, sentence 2 of the Basic Law entitles the MPs to participate in deliberations and decisions in plenary sessions and in parliamentary committees . This is done by the MP's participation in deliberations and votes. The right to make speeches ( Section 27 of the GOBT) and to make suggestions ( Section 20, Paragraph 2, Clause 3 of the GOBT) are elementary rights of participation of the Member . Furthermore, the delegate has the right to question ( § 105 GOBT) and to inspect files ( § 16 GOBT).

According to the wording of Art. 38 GG, the constitutional rights of the member of parliament cannot be restricted. In jurisprudence, however, it is recognized that conflicting constitutional law sets limits on the rights of the member of parliament. This is based on the fact that constitutional provisions stand side by side as principles of equal rank, which is why they do not displace one another. MEPs' rights are limited, for example, by their interest in the functioning of Parliament. For example, the GOBT contains numerous regulations on parliamentary participation, for example in Section 35 GOBT, which limits speaking time in plenary. Furthermore, according to Section 44a (1) sentence 1 of the AbgG , a member of parliament may only perform secondary activities to the extent that they do not hinder the exercise of the office of member.

Factions and groups

Furthermore, the MP has the right to join forces with other MPs to form a parliamentary faction or group .

A parliamentary group is a subdivision of the Bundestag which, according to Section 10 (1) GOBT, comprises at least five percent of the Bundestag members who belong to the same party or to different parties that do not compete with one another. Under constitutional law, the parliamentary group's legal status as an association of members of parliament is rooted in Article 38 (1) sentence 2 of the Basic Law. This is why the parliamentary group, like the individual MPs, has numerous parliamentary participation rights. A parliamentary group right can be restricted by conflicting constitutional law. As such, the interest in the functioning of Parliament comes into consideration. A parliamentary group is an amalgamation of several members who do not meet the requirements of a political group.

The association of MPs harbors the risk that the collective will exert pressure on the individual MPs to act in the interests of the association. Such pressure endangers the freedom of the mandate. This is violated as soon as the association is linked to certain types of behavior on the part of the MPs. In jurisprudence, this is referred to as mandatory faction. Fractional discipline, however, is permissible: this is simply a matter of trying to influence the MPs in favor of the union.

Protection of the MP

The constitution standardizes further parliamentary rights as an expression of Article 38 paragraph 1 sentence 2 of the Basic Law.

According to Art. 46 GG, the member of parliament enjoys indemnity and immunity . The former denotes the protection against legal disadvantages that are linked to an action by the MP in the exercise of his MP. The latter denotes protection from criminal prosecution during the term of office.

Art. 47 sentence 1 GG grants the member the rightto refuse to testify about facts of which he becomes aware in his function as member. This right to refuse to testify is specified in more detail in the procedural rules, for example in Section 53 (1) number 4 of the Code of Criminal Procedure . As far as the right to refuse to testify extends, the MP is alsoprotectedagainst confiscation according to Art. 47 sentence 2 GG.

Art. 48 protects the social and financial position of the MP. Art. 48 paragraph 1 GG grants the member a right to vacation for the election campaign. Article 48 paragraph 2 of the Basic Law prohibits resignation or dismissal of the member because of his mandate activity. According to Article 48 (3) of the Basic Law, the member of parliament continues to be entitled to compensation and free transport by state means of transport.

Litigation position

As a member of the Bundestag, the member of parliament holds a public office. Therefore, as part of his parliamentary activities, he is not protected by fundamental rights as part of state authority . Rather, according to Article 1, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law, it is bound by fundamental rights. If a constitutional body interferes with the right of a member of parliament, the member cannot defend himself with a constitutional complaint. Instead, an application in the Organstreit proceedings is permissible.

However, if the member of parliament complains about the violation of his or her right to be a member of parliament, he can lodge a constitutional complaint in this regard. This is also permissible if the MP complains about the violation of an extra-parliamentary right.

literature

- Christoph Gröpl: Art. 38 . In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 . In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Ed.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- Hans Klein: Art. 38 . In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

- Winfried Kluth: Art. 38 . In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- Siegfried Magiera: Art. 38 . In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- Michael Morlok: Art. 38 . In: Horst Dreier (Ed.): Basic Law Comment: GG . 3. Edition. Volume II: Articles 20-82. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-16-148232-8 .

- Bodo Pieroth: Art. 38 . In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- Horst Risse, Karsten Witt: Art. 38 . In: Dieter Hömig, Heinrich Wolff (Hrsg.): Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Handkommentar . 11th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2016, ISBN 978-3-8487-1441-4 .

- Hans-Heinrich Trute: Art. 38 . In: Ingo von Münch, Philip Kunig (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 6th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-58162-5 .

Web links

- Art. 38 GG on www.gesetze-im-internet.de - by BMJV and BfJ .

- Art. 38 GG on dejure.org - legal text with references to case law and cross-references.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Hans Klein: Art. 38 , Rn. 13. In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

- ↑ a b Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 , para. 1. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ a b Winfried Kluth: Art. 38 , Rn. 5. In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- ↑ Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 , para. 3. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 , para. 3. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ Bodo Pieroth: Art. 38 , Rn. 5. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ Siegfried Magiera: Art. 38 , Rn. 100. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 89, 155 (172) : Maastricht.

- ↑ BVerfGE 123, 267 (328) : Lisbon.

- ↑ Siegfried Magiera: Art. 38 , Rn. 114. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Hans Klein: Art. 38 , Rn. 164. In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (Ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 3, 19 (24) : Quorum of signatures.

- ↑ BVerfGE 95, 335 (349) : Overhang mandates II.

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 38 , Rn. 49. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ^ Annette Guckelberger: Electoral system and principles of electoral law Part II - Equality and the public sphere of the election . In: Juristische Arbeitsblätter 2012, p. 641 (643).

- ^ Christoph Gröpl: Staatsrecht I: State foundations, state organization, constitutional process . 9th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-71257-9 , Rn. 953.

- ↑ BVerfGE 129, 124 (151) : EFS.

- ↑ Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 , para. 5. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 30, 227 (246) : Association name.

- ↑ Bodo Pieroth: Art. 38 , Rn. 4. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 99, 69 (77) : Municipal voter associations.

- ↑ BVerfGE 36, 139 (141) : Right to vote for Germans abroad.

- ↑ BVerfGE 3, 19 (31) : Quorum of signatures.

- ↑ BVerfGE 11, 266 (272) : Voters' Association.

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 38 , Rn. 15. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 3, 45 (49) : Substitutes who are moving up.

- ↑ BVerfGE 7, 63 (68) : List election.

- ↑ Siegfried Magiera: Art. 38 , Rn. 83. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 38 , Rn. 17. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ↑ Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 , para. 22. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 44, 125 (139) : Public Relations.

- ^ A b Christoph Degenhart: State organization law: with references to European law . 31st edition. CF Müller, Heidelberg 2015, ISBN 978-3-8114-4019-7 , Rn. 82.

- ↑ Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 , para. 24. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Hrsg.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ Bodo Pieroth: Art. 38 , Rn. 3. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ Hans-Heinrich Trute: Art. 38 , Rn. 53. In: Ingo von Münch, Philip Kunig (Ed.): Basic Law: Commentary . 6th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-58162-5 .

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 38 , Rn. 19. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 41, 399 (413) : Lump sum for election campaign costs.

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 38 , Rn. 20. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ^ Christoph Gröpl: Staatsrecht I: State foundations, state organization, constitutional process . 9th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-71257-9 , Rn. 365.

- ↑ BVerfGE 95, 408 (418) : Basic mandate clause.

- ↑ BVerfGE 82, 322 : All-German election.

- ↑ BVerfGE 95, 408 (419) : Basic mandate clause.

- ↑ BVerfGE 120, 82 : blocking clause local elections.

- ↑ BVerfGE 129, 300 : Five percent threshold EuWG.

- ↑ BVerfGE 121, 266 : Land lists.

- ^ Annette Guckelberger: Electoral system and principles of electoral law Part II - Equality and the public sphere of the election . In: Juristische Arbeitsblätter 2012, p. 641 (644–645).

- ↑ BVerfGE 95, 408 (420) : Basic mandate clause.

- ↑ Bernd Grzeszick. In: Art. 38 , para. 90-93. In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Ed.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- ↑ Siegfried Magiera: Art. 38 , Rn. 94. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 38 , Rn. 21. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 123, 39 (71) : voting computer.

- ↑ Siegfried Magiera: Art. 38 , Rn. 46. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 60, 374 (380) : Freedom of speech and regulatory law.

- ↑ BVerfGE 1, 144 (153) : autonomy of the rules of procedure.

- ↑ Thomas Harks: The right of the delegates to ask questions . In: Legal Training 2014, p. 979.

- ↑ BVerfGE 118, 277 (324) : Constitutional status of members of the Bundestag.

- ↑ BVerfGE 80, 188 (219) : Wüppesahl.

- ↑ BVerfGE 43, 142 (149) : Constitutional complaint by a parliamentary group.

- ↑ BVerfGE 112, 118 (135) : Mediation Committee.

- ↑ Michael Morlok: Art. 38 , Rn. 176. In: Horst Dreier (Ed.): Basic Law Comment: GG . 3. Edition. Volume II: Articles 20-82. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-16-148232-8 .

- ^ Tassilo du Mesnil de Rochemont, Michael Müller: The legal status of members of the Bundestag Part 1: System of the legal provisions, free mandate . In: Juristische Schulung 2016, p. 504 (505–506).

- ↑ Horst Risse, Karsten Witt: Art. 38 , Rn. 22. In: Dieter Hömig, Heinrich Wolff (Hrsg.): Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: hand commentary . 11th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2016, ISBN 978-3-8487-1441-4 .

- ↑ Tassilo du Mesnil de Rochemont, Michael Müller: The legal status of members of the Bundestag Part 2: Status rights and legal protection . In: Juristische Schulung 2016, p. 603 (604–605).