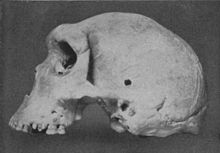

Bodo skull

The Bodo skull (archive number: Bodo 1) is a fossil that was recovered in 1976 by a group of researchers led by Jon Kalb from the Bodo D'Ar site in Middle Awash ( Somali region , Ethiopia ) and was first scientifically described in 1978. At that time it was considered to be one of the most complete and best preserved fossil skull finds from the ancestral line of anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) in Africa . The site and find were named after the nearby river Bodo .

In the Fund layer of the skull were also numerous stone tools from the era of Acheulian discovered. The coordinates of Bodo D'Ar are 10 degrees, 37.5 north; 40 degrees, 32.5 east.

Dating

The age of the find could initially only be roughly estimated on the basis of biostratigraphic findings (700,000 to 125,000 years ago ), but in 1994 the skull was dated to an age of 640,000 ± 30,000 years using the 40 K- 40 Ar method .

description

The Bodo skull was a surface find that had thundered out of the volcanic material of the ground after rainfall and from which Alemayehu Asfaw from the Ethiopian Antiquities Authority was the first to perceive a fragment of the upper jaw. Two large fragments of the upper facial skull lay eleven meters apart, the lower part of the facial skull was also broken into two parts, but their exact fit showed them to belong together. Between the two large fragments of the upper facial skull, another 46 small fragments were discovered in 1976, and two years later another 30 fragments belonging to the skull were found. Due to their fit, a total of 41 finds could be used to reconstruct the original appearance of the skull, but especially the face. In 1981 a partially preserved left parietal bone was finally discovered 400 meters away from the original site , although this was attributed to a second individual of the same age as the Bodo skull. As a result, the face was almost completely restored, but larger gaps remained in the area of the roof of the skull and in the area of the posterior skull plates.

Due to the considerable thickness of its bones, the skull was described as robust and large, but relatively flat, with a wide nose and prominent bulges above the eyes , which is why it can be classified as male and adult. As early as 1978 it was shown that the Bodo skull shares common features with the much younger skulls Kabwe 1 from Zambia and Petralona 1 from Greece , but also with the Arago fossils from southern France and with the much older Homo erectus - skull Sangiran 17 from Java ( Indonesia ). In summary, it was argued in 1978 that the skull is undoubtedly more archaic than fossils belonging to Homo sapiens , but also certainly less archaic than Homo erectus . Because of the still low density of finds in Africa at that time, neither the geographical variability of the early archaic Homo sapiens nor the transition from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens (which was generally assumed at the time) were documented in sufficient detail to allow a clear assignment of the skull to one or the other species or a determination of its position between the two is possible.

After the fragments of the skull in 1982 at the University of California, Berkeley cleaned and reassembled and then to the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa had been returned, published G. Philip Rightmire 1996 a new, detailed description of the skull and its phylogenetic classification. Again, both characteristics of Homo erectus and early Homo sapiens were mentioned and its shape was designated as intermediate. In addition, he was assigned a brain volume of 1200 to 1325 cm³, which clearly exceeds the known dimensions of Homo erectus . Rightmire therefore suggested that the Bodo skull be placed near the European finds from southern France and Greece and identified as a member of the species Homo heidelbergensis . This view - that the "Kabwe-Petralon-Arago-Bodo Group" belongs to Homo heidelbergensis - was also represented in 2015 by Ian Tattersall . This also means that the Bodo skull - in this view - is the oldest fossil evidence of Homo heidelbergensis .

Cuts

In 1986, Tim White reported in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology that on the left, anterior region of the zygomatic bone, several closely spaced notches can be seen which, after a microscopic analysis, could be identified as cutting marks. A detailed examination of the skull surface revealed indications of a total of 17 places with such cuts; No evidence of damage to the surface caused by animal bites was found. According to Tim White, it was the earliest evidence of the removal of muscle tissue by stone tools from a hominini individual at the time .

literature

- Tsirha Adefris: A description of the Bodo cranium: an archaic Homo sapiens cranium from Ethiopia. Dissertation, New York University. New York City 1992.

- Jon Kalb : Adventures in the Bone Trade. The Race to Discover Human Ancestors in Ethiopia's Afar Depression. Copernicus Books, New York 2001, pp. 239-243 and 270-272, ISBN 0-387-98742-8 .

Web links

- Bodo. On: humanorigins.si.edu , last accessed on April 15, 2019

Individual evidence

- ^ Glenn C. Conroy, Clifford J. Jolly, Douglas Cramer, and Jon E. Kalb: Newly discovered fossil hominid skull from the Afar depression, Ethiopia. In: Nature . Volume 276, 1978, pp. 67-70, doi: 10.1038 / 276067a0

- ↑ a b Keyword Bodo 1 in: Bernard Wood : Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4051-5510-6 .

- ^ John Desmond Clark et al .: African Homo erectus: old radiometric ages and young Oldowan assemblages in the Middle Awash Valley, Ethiopia. In: Science . Volume 264, No. 5167, 1994, pp. 1907–1910, doi: 10.1126 / science.8009220 , full text (PDF)

- ↑ Berhane Asfaw: A new hominid parietal from Bodo, Middle Awash Valley, Ethiopia. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Volume 61, No. 3, 1983, pp. 367-371, doi: 10.1002 / ajpa.1330610311

- ^ G. Philip Rightmire: The human cranium from Bodo, Ethiopia: evidence for speciation in the Middle Pleistocene? In: Journal of Human Evolution . Volume 31, No. 1, 1996, pp. 21-39, doi: 10.1006 / jhev.1996.0046 , full text

- ↑ Glenn C. Conroy et al .: Endocranial capacity of the bodo cranium determined from three-dimensional computed tomography. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Volume 113, No. 1, 2000, pp. 111-118, doi : 10.1002 / 1096-8644 (200009) 113: 1 <111 :: AID-AJPA10> 3.0.CO; 2-X

- ^ Ian Tattersall : The Strange Case of the Rickety Cossack - and Other Cautionary Tales from Human Evolution. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2015, p. 186, ISBN 978-1-137-27889-0

- ↑ Tim White : Cut marks on the Bodo cranium: a case of prehistoric defleshing. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Volume 69, No. 4, 1986, pp. 503–509, doi: 0.1002 / ajpa.1330690410 , full text (PDF)