Tuberous sclerosis

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| Q85.1 | Tuberous (brain) sclerosis

Bourneville (Pringle) |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal - dominant inherited disorder associated with malformations and tumors of the brain , skin lesions and usually benign associated tumors in other organ systems and frequently clinically epileptic seizures and cognitive disabilities is characterized.

The prevalence of the disease in newborns is around 1: 8000. After the first descriptions, the French neurologists Désiré-Magloire Bourneville (1840-1909) and Édouard Brissaud (1852-1909) as well as the British dermatologist John James Pringle (1855-1922), this disease is often called Bourneville-Pringle syndrome or Bourneville syndrome. Called Brissaud-Pringle Syndrome . In the English-speaking world, the term Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) has become established to highlight the complex of various symptoms and clinical pictures in this disease from the group of phakomatoses .

Malformations and tumors of the brain

Malformations and tumors of the brain are often detected early. Cortical glioneuronal hamartomas , the so-called tubera (protrusions) in the area of the cerebral cortex, are often associated with epilepsy and can cause cognitive impairment, while subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and subependymal nodules typically lead to the development of hydrocephalus due to their proximity to the ventricular system.

epilepsy

Epileptic seizures are very common in tuberous sclerosis and can occur as early as the first few months of life. With the exception of typical absences, all types of seizures are possible. The most common type of seizure in early childhood is epileptic spasm, and West syndrome is often diagnosed in infants . Overall, seizures occur in over 70% of children with tuberous sclerosis and cannot always be treated satisfactorily with medication. A connection between seizure frequency and learning difficulties could be proven. Rapidly secondary generalizing partial seizures are often most common in adults.

Developmental disorders

Developmental disorders with impairment of language and movement development, but also learning disorders can pose problems; Sometimes behavioral problems can be in the foreground. The extent of the disability, however, is extremely heterogeneous: In one study, on the one hand, over half of the patients had a normal IQ , while 31% of those examined with an IQ below 21 had very serious limitations.

Skin changes

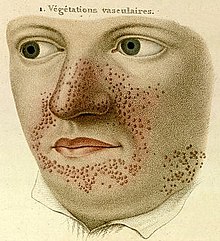

Skin changes come in different forms and sometimes occur depending on age. The first skin changes are harmless pigment disorders, white leaf-shaped spots on the body (so-called ash-leaf spots ) and occur in over 80% of patients in the first year of life. Their recognition is made easier by the Wood lamp . In later childhood, reddish papules typically appear symmetrically in the area of both nasolabial folds . These are angiofibromas , benign hamartomas that were first described in Traité théorique et pratique des maladies de la peau (Paris 1826–1827, 1835) by Pierre François Olive Rayer and in 1890 by John James Pringle for the first time as adenoma sebaceum. Slightly raised leather-like, consolidated lumbosacral skin lesions, which are referred to as “ shagreen patch” (up to 40%), are also typical . Rough, reddish fibromatous nodules from the nail fold are known as Koenen's tumors and occur in 22% of patients in late childhood.

Other organ systems

Outside the brain, benign tumors called angiomyolipomas and kidney cysts appear in the kidneys . These changes often do not cause any symptoms, but can rarely degenerate into a malignancy. In many children, so-called rhabdomyomas , tumors of the muscle tissue, are diagnosed in the heart from birth . These tumors, first described by Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen (1833–1910), do not cause serious problems in most cases. They grow until birth and then usually regress; which factor causes this is not yet known. If the skin is involved, cutaneous angiofibromas ( adenoma sebaceum ) occur. The lungs ( lymphangioleiomyomas ) and other organs of the body can also be attacked by tumors.

Inheritance

Tuberous sclerosis is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. This means that the disease can be inherited by an affected person with a probability of 50%. In 30% of all affected people, the inheritance occurred through the father or mother. The disease occurred sporadically in the remaining 70% and was caused by a new mutation . Even if there are only minor symptoms of tuberous sclerosis, there is a possibility that children can develop a severe form of tuberous sclerosis. In affected families who want to have children, genetic counseling from a specialist in human genetics is therefore recommended. A molecular genetic examination of an affected family member can be helpful in assessing the likelihood of recurrence if the mutation causing the disease in one of the genes for tuberous sclerosis ( TSC1 on chromosome 9 gene locus q34 and TSC2 on chromosome 16 gene locus p13.3) is identified and then targeted can be examined for this mutation. With the help of conventional molecular genetic methods (exon sequencing and MLPA), mutations or deletions in the area of the TSC1 or TSC2 gene can be detected in around 85% of patients.

The two proteins encoded by the genes TSC1 and TSC2 belong to a TSC protein complex, which is a critical negative regulator of the mTOR complex 1, which is critical for regulating cell growth and cell size, which are critical prerequisites for cell division. The (intact) TSC protein complex thus inhibits growth and mitosis and thus indirectly acts as a tumor suppressor .

Therapy and prognosis

There is currently no causal therapy for tuberous sclerosis; treatment is limited to the symptoms, especially those of epilepsy. In addition to neurosurgical options, immunosuppressive drugs that inhibit the mTOR signal cascade are now also available for treating malformations and tumors of the brain. Many people with low-level tuberous sclerosis lead largely normal lives. If it is more pronounced, however, life expectancy can be limited, particularly in the case of severe epilepsy , pronounced cognitive impairments and the occurrence of tumors.

literature

- Kurt Kallenbach (ed.): Children with special needs. Selected clinical pictures and forms of disability. Ed. Marhold, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-89166-208-4 .

Web links

- Tuberous sclerosis. In: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man . (English).

- Tuberous Sclerosis Germany eV with lots of information

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bourneville & Brissaud: Encéphalite ou sclérose tubéreuse des circonvolutions cérébrales. Archives de neurologie, Paris, 1881, 1, pp. 390-412.

- ↑ Webb et al .: Morbidity associated with tuberous sclerosis: a population study. In: Dev Med Child Neurol . 1996; 38 (2), pp. 146-155. PMID 8603782

- ^ Hunt: Development, behavior and seizures in 300 cases of tuberous sclerosis. In: J Intellect Disabil Res. 1993; 37, pp. 41-51. PMID 7681710 .

- ^ Asato & Hardan: Neuropsychiatric problems in tuberous sclerosis complex. In: J Child Neurol. 2004; 19 (4), pp. 241-249. PMID 15163088

- ↑ Joinson et al .: Learning disability and epilepsy in an epidemiological sample of individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex. In: Psychol Med. 2003; 33 (2), pp. 335-344. PMID 12622312 .

- ↑ Barbara I. Tshisuaka: Rayer, Pierre François Olive. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1216 f.

- ↑ Pringle: A case of congenital adenoma sebaceum. In: British Journal of Dermatology . 1890; 2, pp. 1-14.

- ↑ Kane et al .: Color Atlas & Synopsis of Pediatric Dermatology. McGraw-Hill Professional, 2001, ISBN 0-07-006294-3 .

- ↑ Webb et al .: A population study of renal disease in patients with tuberous sclerosis. In: Br J Urol . 1994; 74, pp. 151-154. PMID 7921930 .

- ^ V. Narayanan: Tuberous sclerosis complex: genetics to pathogenesis. In: Pediatr. Neurol. 2003; 29 (5), pp. 404-409. PMID 14684235

- ↑ David J. Kwiatkowski, Brendan D. Manning: Molecular Basis of giant cells in tuberous sclerosis complex. In: New England Journal of Medicine . 2014, Volume 371, Issue 8 of August 21, 2014, pp. 778-780; doi: 10.1056 / NEJMcibr1406613 .

- ↑ Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, et al .: Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. In: N Engl J Med . tape 363 , 2010, p. 1801-1811 .