Crónica Albeldense

The Crónica Albeldense (Chronicle of Albelda, Latin: Chronicon Albeldense ) is a chronicle written in the Kingdom of Asturias at the court of King Alfonso III. (866-910) was written.

Emergence

The author is unknown - it was previously assumed that the author was a Toledan clergyman named Dulcidius , who is mentioned at the end of the Chronicle, but research has deviated from this view. According to current research, it can be assumed that he was a clergyman who worked at the royal court of Oviedo in the vicinity of King Alfonso III. lived. He may have been in the city of León for a long time , and he was very familiar with its circumstances.

The original version of the work only extends until the year 881, in which it was completed; later the chronicler added two longer sections covering the years 882 and 883. In November 883 he finished the latest version.

content

The work begins with a brief summary of the geography of the world and then gives an enumeration of geographical data on the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces, cities and rivers and an overview of the chronology of world history since Adam , the ancestor of mankind. Then the history of the Roman Empire from Romulus to the Byzantine Emperor Tiberios II (698–705) is dealt with. It follows the history of the Visigoths, beginning with King Athanaric , and in particular of the Visigoth Empire on the Iberian Peninsula up to King Roderich (710–711), with whom the empire fell. It concludes with the history of the Kingdom of Asturias from Pelayo (718–737) to the present day of the author. The representation becomes more and more detailed the closer it is to the time of the chronicler. At the same time the style changes; the older story is summed up in dry words, the deeds of Alfonso III. describes the chronicler as a knowledgeable contemporary in detail and vividly. He glorifies this ruler, whose military success he describes as a “holy victory”, thereby anticipating the later interpretation of the struggle against the Muslims as a holy war .

Historical context and source value

King Alfonso III showed a keen interest in historiography. His aim was to prove his empire as a legitimate renewal of the Visigoth empire destroyed by the Muslim invasion ("Neo-Gothic"). Three historical works that were written at his court served this purpose: the "Chronicle of Alfonso III", which the king himself was involved in drafting, which has been preserved in two editorial offices, the Crónica Albeldense and the "Prophetic Chronicle", which was completed in April 883. These three chronicles are summarized by research under the term "Cycle of Alfonso III". In the Crónica Albeldense and the Chronicle of Alfonso III. partly the same news material was evaluated, as can be seen from the formal and content-related matches.

The chronicles of the cycle are based on a tradition in which the downfall of the Visigothic Empire is interpreted as a divine punishment for the sinfulness of the last Visigoth kings and the military successes of the Asturian kings appear as a reward for their piety. In order to convince the reader of this historical image, its Asturian originator did not shy away from deliberate historical falsification. Nevertheless, modern historians regard the “Alfonso III cycle” with great esteem, because it is the only chronical source from the entire epoch of the Kingdom of Asturias (718–910); without them almost nothing would be known about the beginnings of the Reconquista . The Asturian chronicles also offer valuable, albeit tendentious, information for the late Visigothic period.

Handwritten tradition

The Crónica Albeldense is handed down in four medieval manuscripts ( Codices ), of which the two oldest and most important, the “Codex Aemilianensis” and the “Codex Albeldensis”, date from the 10th century. The most complete version contains the Codex Aemilianensis, a copy from the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla , which is now kept in the library of the Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid.

The handwriting from Albelda

The name Albeldense was given to the chronicle from the transcript from the monastery of San Martín de Albelda in Albelda de Iregua , La Rioja , copied and continued with lists of kings until 976 by the monk Vigila (Spanish: Vigilán ). The full modern name is Codex conciliorum Albeldensis seu Vigilanus , but it is sometimes referred to simply as Codex Vigilianus .

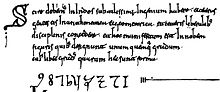

The manuscript comprises 429 large-format pages (455 × 325 mm), which are described in two columns in Visigoth script . This manuscript, which was luxurious for the time, was completed in 976 by the monk Vigila and his assistants Sarracino and García. Vigila mentions his comrades-in-arms in a final note, and they appear with him alongside other people in one of the best miniatures .

The manuscript is a unique compilation of canonical and civil law and an invaluable source of knowledge about the Visigoth as well as the Asturian and Galician kingdoms . It contains a collection of acts of the council and a list of the general councils as well as a selection of canons and decretals of the popes up to Gregory the great , a contemporary of Isidore of Seville . There is also a collection of laws that were valid from the Visigothic epoch (then under the name Liber iudiciorum ) to modern times (since the 13th century in Castilian translation as Fuero Juzgo ). Other texts are of a historical and liturgical character, such as the Vida de Mahoma (description of the life of the Prophet Mohammed from a Christian perspective), the Crónica Albeldense and a calendario in which the Arabic numerals 1 to 9 appear for the first time in a European document.

There are also 82 miniatures in lively colors: some full-page cityscapes (e.g. of Toledo ) or portraits of important personalities. Although they are the work of Spanish monks, these works are not based on Visigothic or Mozarabic models, but on the works of Carolingian miniaturists.

The codex came from a donation from the Count of Buendía to Philip II and is now one of the jewels in the library of the former monastery residence El Escorial .

The monastery of San Martín de Albelda was one of the cultural centers of the country in the 10th century under the rule of the Pamplona kings, even more important than the also famous monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla. It had an active and well-organized scriptorium in which the monks copied the books necessary for the Mass and the spiritual life, but also legal texts. The reputation of the monastery extended beyond the country's borders: in the middle of the 10th century, the French bishop Godeschalk von Puy visited it on his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and had a treatise by St. Ildefons on the virginity of Mary copied.

Text output

- Yves Bonnaz (Ed.): Chroniques asturiennes. Editions du Center national de la recherche scientifique, Paris 1987, ISBN 2-222-03516-3 (contains the Latin text with a French translation and a detailed French commentary).

- Juan Gil (Ed.): Chronica Hispana saeculi VIII et IX (= Corpus Christianorum . Continuatio Mediaevalis , Vol. 65). Brepols, Turnhout 2018, ISBN 978-2-503-57481-3 , pp. 435-484 (critical edition)

- Juan Gil Fernández (Ed.): Crónicas asturianas. Universidad de Oviedo, Oviedo 1985, ISBN 84-600-4405-X ( Universidad de Oviedo. Publicaciones del Departamento de Historia Medieval 11), (Latin text and Spanish translation).

Web links

- Text (Spanish) about the Codex of Albelda with two illustrations

- Images from the facsimile edition (span.)

Remarks

- ^ Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz: El autor de la Crónica llamada de Albelda : In: ders .: Investigaciones sobre historiografía hispana medieval . Buenos Aires 1967, pp. 66-79; Bonnaz S. LIX-LX.

- ↑ For the chronicler's style and ideas, see Alexander Pierre Bronisch: Reconquista and Holy War - the interpretation of war in Christian Spain from the Visigoths to the early 12th century . Münster 1998, pp. 141-144.

- ↑ For Neo-Gothic and the connections between the chronicles of the cycle see Jan Prelog: Die Chronik Alfons' III. Frankfurt a. M. 1980, S. CXLIII – CLXIII (overview of older research ibid. S. XLVI – LXXIX); Bonnaz S.LXXXVIII-XCIII; Bronisch (1998) pp. 371-395.

- ↑ Prelog S. CXLIII-CXLVI.

- ↑ See e.g. B. the summarizing appreciation of Juan Ignacio Ruiz de la Peña in the introduction to the text edition by Gil, p. 41f.