Daphne Palace

The Daphne Palace was one of the main wings of the Great Palace of Constantinople in Byzantine times. According to the pseudo-Kodino , the palace was named after a statue of the nymph Daphne , which was brought from Rome.

History and description

The Daphne Palace was built in the earliest construction phase of the Great Palace under Constantine the Great , who expanded the city of Byzantion into his capital, Constantinople, and made it the center of the empire. Justin II , who ruled from 565 to 568, extended the original building, which was the residence of the emperors until the 8th century AD.

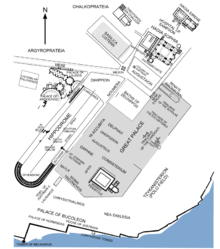

The building complex consisted of ceremonial buildings and living areas and was located in the western part of the entire imperial complex directly next to the hippodrome and connected to the cathisma via a staircase . The complex included the living wing with the sleeping quarters of the emperor ( koitōn ), the octagon and the Stephanos chapel, which was built around 421 by the empress Aelia Pulcheria to keep the right arm of the saint as a relic . The Daphne Palace was connected to the dining room ( triklinos ) of Augusteus , one of the oldest parts of the palace. The spacious hall was also known under the name Stepsimon ( Greek Στέψιμον , German coronation ), which suggests its function as the coronation hall of the palace. The hall had this function especially for the coronation of the empresses, but was also the place of imperial weddings up to the middle Byzantine period. The Augusteus was connected to the later built Trikonchos Palace and the hall of the consistory . The location of two later built chapels dedicated to St. The Virgin Mary and the Trinity were found in the southern part of the Daphne complex.

In the 9th and 10th centuries the center of court life shifted to the south of the palace complex towards the Bukoleon Palace and the ceremonies in the chrysotriclinos . Nevertheless, the Daphne Palace remained the site of imperial ceremonies, as described in the De Ceremoniis of Constantine VII . The decline of the palace is documented quite well by the measure of Emperor Nikephoros II (reign 963–969), who surrounded the Great Palace with new walls and excluded the Daphne Palace.

After the 11th century, the palace seems to have been increasingly dilapidated and gradually destroyed. The process intensified when the Latins looted the complex and extracted metals and architectural elements during the period of the Latin Empire (1204–1261).

architecture

The exact appearance of the building complex has not been handed down, as excavations are not possible due to the location under the Sultan Ahmed Mosque and the only sources of its appearance come from literary sources. The art historian Jonathan Bardill suspects, however, that the peristyle with mosaics connected to a hall with an apse and that this hall, discovered during the excavations of the Walker Trust Excavations in the years 1935 to 1937 and 1952 to 1954, could have been the Augustaion of the palace.

literature

- Henry Maguire (Ed.): Byzantine court culture from 829 to 1204 . Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC 2004, ISBN 978-0-88402-308-1 .

- AG Paspates: The Great Palace of Constantinople . London 1893 (reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-7661-9617-8 ).

- Jan Kostenec: Observations on the Great Palace at Constantinople: The Sanctuaries of the Archangel Michael, the Daphne Palace, and the Magnaura . In: Reading medieval studies 31, 2005, pp. 27–56 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- Nigel Westbrook: Great Palace in Constantinople . In: Constantinople (= Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World , Volume 3), Foundation of the Hellenistic World, Athens 2008 ( digitized version ).

- Reconstruction of the palace , Byzantium 1200 project

Individual evidence

- ↑ Paspates (1893), S. 227th

- ↑ a b c d Westbrook (2008)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 , p. 869.

- ↑ Paspates (1893), pp. 229-233.

- ^ Maguire (2004), p. 57.

- ↑ Maguire (2004), pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Paspates (1893), pp. 233-235.

- ↑ Paspates (1893), pp. 236-237.

- ↑ Jonathan Bardill: The Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors and the Walker Trust Excavations . In: Journal of Roman Archeology 12, 1999, pp. 216-230 doi : 10.1017 / S1047759400017992

Coordinates: 41 ° 0 ′ 21.6 ″ N , 28 ° 58 ′ 33.6 ″ E