Chrysotriclinos

The Chrysotriklinos ( Greek Χρυσοτρίκλινος , dt. Golden reception hall ; Latinized Chrysotriclinus or Chrysotriclinium ) was the main reception and ceremonial hall of the Great Palace of Constantinople . The building was built in the late 6th century and maintained its function until the 10th century. Its appearance is known only through literary descriptions, mainly the De cerimoniis of Constantine VII , which describes the imperial ceremonies.

history

It is generally assumed that the chrysotriclinus was begun by Emperor Justin II (reign 565-578) and completed and embellished by his successor Tiberius II (reign 578-582). Byzantine sources also name other builders: The Suda ascribes the building to Justin I (reign 518-527) and the Patria Konstantinupoleos names Emperor Marcian (reign 450-457) as the builder. The Byzantine historian Johannes Zonaras reported that Justin II actually built an older building. It is believed that this could have been a hall with seven conches of Justinian I (reign 527-565).

After the Byzantine iconoclasm , the emperors Michael III. (Reign 842–867) and Basil I (reign 866–886) of the Chrysotriklinos from new. Unlike many other buildings in the Grand Palace that were built for one purpose only, the Chrysotriklinos combined the functions of a throne room for receptions and audiences with those of a banquet hall. After further imperial rooms were added later, the hall took a central position in the everyday life of courtly ceremonies, especially in the 9th and 10th centuries, when Constantine VII (reign 945-959) called it "the palace". After the De Cerimoniis , the emperor used the chrysotriklinos primarily for receptions of foreign ambassadors, for meetings with dignitaries, as a meeting place for religious celebrations and as a ballroom for celebrations such as Easter.

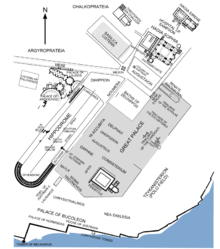

As a result, the Chrysotriklinos became the central component of the new Bukoleon Palace , which was built when Emperor Nikephoros II (reign 963-969) enclosed the southern part of the palace facing the Propontis with a wall. From the 11th century, the Byzantine emperors preferred the Blachernen Palace in the north-west of Constantinople as their residence. During the Latin Empire (1204-1261) the emperors used the Bukoleon Palace and Michael VIII also lived here after the restoration of the Byzantine Empire, while the Blachernen Palace was rebuilt. After the Byzantine emperor moved to the renovated palace, the Great Palace was hardly used any more and became increasingly dilapidated. The chrysotriclinus was last mentioned in 1308, although the mighty ruins remained until the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453.

architecture

Despite its importance and frequent mentions in Byzantine texts, there is no detailed description of the structure. The hall appears to have been octagonal in plan and topped by a dome like other Byzantine buildings of the 6th century, including the Sergius and Bacchus Church in Constantinople and the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna . The roof was supported by eight arches with apses or wall niches and illuminated by 16 windows. It was assumed that the layout and appearance of the chrysotriclin were later adopted by Charlemagne during the construction of the Aachen Cathedral , but San Vitale was more likely the model.

The imperial throne stood in an eastern apse in the bema behind a bronze railing. The north-western apse was known as the Chapel of St. Theodore . The imperial crown and some relics, including the staff of Moses, were kept there . The apse also served as a dressing room for the emperor. The southern apse led through a silver door that Constantine VII had built into the imperial apartments ( koitōn ). The north apse was known as the Pantheon , a waiting room for dignitaries, while the northwest apse served as a diaitarikion and was intended for the servants. It was also the place where the palace key was kept, the symbol of Papias who used it to unlock the palace every morning.

The main hall of the Chrysotriklinos was surrounded by other halls and extensions: a vestibule ( tripeton ), the horologion (probably so named because a sundial was located here), the hall of the Kainourgion ("new hall") and the halls of Lausiakos and Justinianos for Justinian II (reigns 685-695 and 705-711). The Pharos Palace Chapel , the main chapel of the palace, joined to the south or south-east.

Nothing is known about the decoration of the hall from the 6th century. After the ban on human images during the Byzantine iconoclasm, the hall was redesigned between 856 and 866 with monumental mosaics. The ambassador Liutprand of Cremona described the hall as "the most beautiful room in the palace". Above the imperial throne was an image of Christ enthroned, while one above the entrance depicts St. Maria portrayed with Emperor Michael III. and the Patriarch Photios I next to it. Elsewhere, the Last Judgment was depicted with angels, priests, and martyrs. All of the embellishment should represent the analogy between Christ's last judgment in heaven and the Byzantine court on earth.

In the hall there was valuable furniture such as the Pentapyrgion ( Eng . Five towers ), a cabinet by Theophilos with vases, crowns and other valuable objects. During imperial banquets , a gold table was set up for the 30 highest dignitaries and two to four additional tables for 18 people each. Occasionally it is described that the emperor had his own table apart from the others. The full pomp of the hall was reserved for exceptional occasions, including banquets for Arab ambassadors. The De ceremoniis describes that additional light was created by large candlesticks, imperial insignia, relics and other valuable objects were brought from various churches and displayed in the apses. During the meal music was played on two silver and two gold organs in a vestibule. The choirs of Hagia Sophia and the Apostle Church sang .

literature

- Robin Cormack: But is it Art? . In: Eva Rose F. Hoffman (Ed.): Late antique and medieval art of the Mediterranean world . Wiley-Blackwell, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-5 , pp. 301-314.

- Michael Jeffrey Featherstone: The Chrysotriklinos seen through De Cerimoniis . In: Lars M. Hoffmann, Anuscha Monchizadeh (Ed.): Between Polis, Province and Periphery. Contributions to Byzantine history and culture (= Mainz publications on Byzantine studies 7). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 845-852 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- Jan Kostenec: Chrysotriklinos . In: Constantinople (= Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World , Volume 3), Foundation of the Hellenistic World, Athens 2008 ( digitized version ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Cormack (2007), p. 304.

- ↑ a b c d e f Kostenec (2008)

- ↑ a b c Cormack (2007), p. 305.

- ↑ a b c Cormack (2007), pp. 304-305.

- ↑ Cormack (2007), pp. 305-306.

- ^ A b The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 , p. 455.

- ^ Heinrich Fichtenau : The Carolingian empire . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1978, ISBN 978-0-8020-6367-0 , p. 68.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 , pp. 455-456.

- ↑ Cyril Mango : The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453. Sources and Documents . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1986, ISBN 978-0-8020-6627-5 , p. 184.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 , pp. 455, 1625.

- ^ Mabi Angar: Furniture and Imperial Ceremony in the Great Palace: Revisiting the pentapyrgion . In: Michael Featherstone, Jean-Michel Spieser, Gülrü Tanman, Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt (Eds.): The Emperor's House Palaces from Augustus to the Age of Absolutism . De Gruyter, Berlin 2015, pp. 184–186.

- ↑ Cormack (2007), p. 306.