Import quota

An import quota is a direct temporal import quantity restriction for an import good. It belongs to the group of non-tariff trade barriers and is intended to have a protective effect for certain domestic sectors . A country uses this instrument as part of its foreign trade policy in order to gain an advantage at the expense of another country. The synonymously used term import quota (composed of import [lat.], The import and quota [lat.], The proportion; opposite: export quota ) is a loan translation of the English term import quota .

Characteristic

In the case of a quantity quota, imports are restricted directly for the importers on the basis of the imports of the previous year, e.g. by specifying weights, quantities and dimensions, etc. The import quota is usually implemented by issuing licenses according to a certain catalog of criteria, both free of charge as well as for a fee or in the form of an auction to the companies or individuals. In principle, auctioning is the way more in line with the market, since black markets are likely to arise in the fee-based award . The right holders can come from Germany or abroad. Allocation to foreign countries is also practiced. The import quota can extend to foreign trade with certain countries or to all countries in general. A quota of “0” is called an embargo ; A current example can be found for chicken legs produced in the USA and treated with chlorine, which are not allowed to be imported into the European Union .

The license holders buy the goods on the international market at the world market price and resell them on the domestic market at the higher domestic price. This difference is called the quota rent (license profit).

The most common cases of protectionist measures in the world are found in the agricultural sector. Well-known import quotas that are often cited and examined in specialist books are for example the quotas for:

- Sugar and cheese in the United States ,

- Bananas and textiles and clothing in the European Union,

- Meat imports to Russia ,

- completely renewed tires from Paraguay to Brazil etc.

Monitoring and licensing in the Federal Republic of Germany is carried out by the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) .

Goals and reasons

The primary goal of countries using an import quota is to protect domestic producers from the low prices that would arise as a result of import competition.

The use of an import quota is justified by the practicing states with the

- Protection of established or even declining economic sectors from competition from mostly developing and emerging countries (see also: Rent-Seeking ),

- Protection for the development of young branches of industry in the form of an educational tariff according to Friedrich List , since the development of these new branches of industry should reduce the dependence on imports (see also: Rent-Shifting and Rent-Creation ),

- Self-sufficiency argument , since a country wants to protect its import substitutes in view of future supply crises,

- Security argument to protect key industries such as the armaments industry,

- Argument to prevent or slow down structural change , as the mostly short-term negative consequences resulting from a necessary structural change should be reduced, extended over time or socially cushioned or

- Protection against unfair competition due to the threat of cheap competition from mostly developing and emerging countries.

The establishment of import quotas is perceived by many experts as counterproductive. In a survey of economists who worked in companies, the state and universities, 93 percent of those questioned agreed with the thesis that tariffs and import quotas reduce general economic prosperity. One of the reasons given for a negative attitude is that an import quota - like the other non-tariff trade barriers - certainly has a short-term protection effect for the economic sectors concerned , but in the medium to long term important structural adjustment processes of the domestic industry would be postponed. The discrimination against foreign providers can also lead to retaliation or Lead to retaliation measures in the affected countries. Disadvantaged countries can also force an abolition through an arbitration procedure under the GATT.

Historical background

At the end of the 19th century, the major industrial nations in Europe and the USA issued tariff trade barriers in the form of import duties for certain industrial products from new industrial sectors. Many countries also did not levy any income tax at the time, so that in some countries the tariffs were the only source of income for the state.

To promote world trade and the global economy was initially 23 states that on 30 October 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (English: General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade; abbr .: GATT) ratified after the plan for an International Trade Organization (ITO) could not be realized. The multilateral agreement came into force on January 1, 1948. With this treaty, the signed states have committed themselves in lockstep to reduce and eliminate trade restrictions.

Since the customs tariffs, which are still regularly approved by the GATT, hardly allow any room for maneuver for the protection of local industry, the move was made to create so-called non-tariff barriers. This is due to the fact that, despite the agreement, the signed member states still have a need for protectionism. The GATT has listed around 600 different forms of such non-tariff trade barriers. The most important ones include import quotas, voluntary export restrictions , local content clauses, etc.

Comparison with other foreign trade instruments

Both the import quota and the other non-tariff trade barriers have many advantages over tariffs. In principle, they protect more reliably, precisely and directly. E.g. if they are to be used flexibly, have a large scope for action, are subject to little transparency, have the possibility of legitimation with the connection of special national interests etc. Certain effects similar to those of the tariffs can also be achieved with them. It is also possible to combine an import quota with a tariff by allowing a certain amount that is not subject to a tariff to be imported, but with a tariff surcharge on imports beyond this.

The objectives of an import quota can be specified by the respective country in a protectionist manner, both directly as a disclosed volume quota, and indirectly (e.g. as a direct result of economic policy measures and legal regulations, for example in the form of the German Purity Law or the GS mark ).

Theoretical modeling

Basic assumptions

The model for describing the effect of an import quota is based on the following simplifying assumptions:

- The study of this political foreign trade instrument takes place within the framework of the partial equilibrium .

- The world consists of only two countries - domestic and foreign.

- In each of these countries only one good is produced and consumed, which can be transported from one country to another free of charge.

- In both countries there is complete competition in the industry of this good , so the supply and demand curves are functions of the market price .

- Rising marginal costs ensure that an expansion of production leads to rising prices, because large companies in this model do not have any economies of scale that influence the market .

- The exchange rate between the currencies of the two countries remains unaffected by any foreign trade policy in this market; prices for both markets are quoted in local currency.

- The case of a small country is assumed, i.e. H. the world market price is not affected by changes in domestic supply and demand as a result of the quantitative import restriction.

Due to the model representation, the explanation of the effect of an imposed import quota can only be a basic guide.

Graphic representation of an import quota

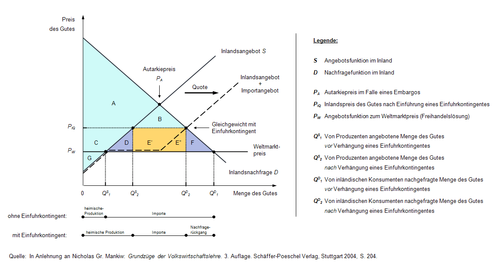

The following graphic is intended to compare the situation of free trade of an imported good between two countries with a market situation after the introduction of a trade restriction by quoting imports. (The capital letters refer to the regions of the diagram.):

The supply curve P W is completely elastic and therefore horizontal here. P A represents the self-sufficiency price in the event that the domestic market is completely sealed off from imports. P IQ is now the new equilibrium price after an import quota has been imposed . As can be seen in the graphic, P IQ is thus moving closer to the equilibrium without foreign trade (self-sufficiency case). This is due to the fact that the import quota prevents domestic consumers from purchasing as much of the good abroad as they want. The result is that the supply at the world market price is no longer completely elastic. If the domestic price is now above the world market price, the license holders will try to import as many goods as possible in order to reap the quota profit. The supply of the goods then corresponds to the domestic supply plus the contingent from the import quota. This means that the supply curve is shifted to the right above the world market price by the quota amount. The supply curve below the world market price does not shift because in this case the import is not economical for the licensees.

Result

As a result of the supply shortage in the import quota, the domestic market price of the imported good increases from P W to P IQ ( price effect ) and leads to a decrease in demand for the good from Q D 1 to Q D 2 ( demand or consumption effect ). The equilibrium amount of domestic supply increases from Q S 1 to Q S 2 ( production effect ). Total consumption in the importing country is falling despite increasing production. This leads to redistribution effects from consumers ( loss of purchasing power) to domestic and foreign producers (price increases). The immediate result of an import restriction is an increase in demand at the original price via domestic supply including imports. The price rises to the level at which the market is just about to be cleared.

| Comparison of a market situation with and without quotas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without a quota | With quota | comparison | |

| Producer surplus | G | C + G | + C |

| Consumer surplus | A + B + C + D + E '+ E' '+ F | A + B | - (C + D + E '+ E' '+ F) |

| Licensee Pension | Nothing | E '+ E' ' | + (E '+ E' ') |

| Total employee pension | A + B + C + D + E '+ E' '+ F + G | A + B + C + E '+ E' '+ G | - (D + F) |

Due to the allocation of imports to domestic consumers lose consumer surplus C + D + E '+ E' + F . In contrast, the total pension increases of domestic producers to the additional producer surplus C . Furthermore, the pensions E '+ E' 'are transferred from the consumers to the import license holders. The total pension taker comes to the two triangles D + F back. If the rights are not auctioned, the entire economic loss of efficiency or Deadweight loss the triangles D + F and the quota rent E '+ E' ' . As a result, the terms of trade between the two countries deteriorate to the disadvantage of the country that introduced the import quota. The effect on the welfare of the nation is inconsistent; it falls for small countries that have no influence on the world market price of the good. Tariffs and import quotas can only be used by large countries that are able to depress world market prices.

Since the quota rent accrues to the license holders, an import quota can - depending on the state's awarding practice - mean that, unlike an import tariff, it does not bring the state any additional direct income. This is the case when the rights are issued to the domestic importers free of charge. The importing country also does not skim off the quota gain if the country protects its sectors in need of protection against a single country or interested foreign providers in the form of an individual quota or against all countries or all interested foreign providers with the help of global quotas . This can also be done through voluntary self-restraint agreements. Such bilateral trade agreements are generally enforced at the request of the importing country. As a result, the countries in turn auction the import licenses on to the local companies and thus siphon off the quota rent. If the import quotas, as already mentioned above, are given directly to interested foreign producers, in this case the foreign suppliers realize the difference between the world market price and the domestic price. Even with this form of quota, the state fails to skim off the quota from foreign providers. This is only possible if import quotas are auctioned by government agencies in the form of public auctions.

Example of an import quota

Assumptions:

- World producer price:

- Domestic demand curve:

- Domestic supply curve:

Calculation:

In the case of free trade, the domestic equilibrium price corresponds to the world market price of 20 MU / ME.

- The domestic demand is:

- The internal offer is:

- The imports are thus:

- By resolution of the government, imports are to be limited to 20,000 ME:

- Establishment:

- Resolution:

Result:

The introduction of the import restriction implies an increase of 10 MU / ME to the new equilibrium price of 30 MU / ME.

- In the figure, the loss of consumer surplus equals the area of the trapezoid:

- The producer surplus increases by the trapezoid:

- The quota rent accruing to the import right holders resembles the rectangle:

- If the rights are not auctioned, the nation's total deadweight loss is:

Individual evidence

- ^ Eckart Koch: International economic relations . Franz Vahlen Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-8006-1593-2 , p. 157.

- ↑ AFP / ras: Chlorine chickens are not on the table. Die Welt, December 18, 2008, accessed June 19, 2013 .

- ↑ Import licensing. World Trade Organization (WTO), accessed June 20, 2013 .

- ↑ Import Guide. (PDF; 183 kB) Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA), January 1, 2012, accessed on June 20, 2013 .

- ^ Eckart Koch: International economic relations . Franz Vahlen Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-8006-1593-2 , p. 147.

- ^ Richard M. Alston, JR Kearl, and Michael B. Vaughn: Is There Consensus among Economists in the 1990s? . In: The American Economic Review . 2./82., 1992, pp. 203-209 ( JSTOR ).

- ^ Eckart Koch: International economic relations . Franz Vahlen Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-8006-1593-2 , p. 155.

- ↑ Homepage. World Trade Organization, accessed June 20, 2013 .

- ^ Helmut Wagner: Introduction to world economic policy . 4th, updated and expanded edition. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-25133-3 , p. 34.

- ^ Eckart Koch: International economic relations . Franz Vahlen Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-8006-1593-2 , p. 154.

- ^ Paul R. Krugman, Maurice Obstfeld: Internationale Wirtschaft. Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade . 7th edition. Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7199-6 , p. 255.

- ↑ The variables used here refer to the graphic above: Graphic representation of the effects of an import quota.

- ^ Paul R. Krugman, Maurice Obstfeld: Internationale Wirtschaft. Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade . 7th edition. Pearson StudiuISBN 3-8273-7199-6, p. 262.

- ↑ Wolfgang Eibner: Application-oriented foreign trade: theory & politics . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-58140-6 , p. 179.

Literature sources

- Gustav Dieckheuer: International economic relations . 5th, completely revised edition. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-486-25806-0 .

- Avinash K. Dixit, Victor Norman: Foreign Trade Theory . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-24755-7 .

- Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-486-22984-2 .

- Klaus Macharzina, Martin K. Welge: Concise dictionary of export and international companies . Carl Ernst Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-7910-8029-6 (Encyclopedia of Business Administration, Volume XII).

- Nicholas Gr. Mankiw: Fundamentals of Economics . 3. Edition. Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-7910-2163-X .

- Klaus Rose, Karlhans Sauernheimer: Theory of foreign trade . 14th edition. Franz Vahlen Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8006-3287-X .

- Horst Siebert: Foreign trade . Franz Vahlen Verlag, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-8252-8081-0 .

- Joachim Zentes, Dirk Morschett, Hanna Schramm-Klein: Foreign trade . Gabler Verlag, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-409-12511-6 .

![20,000ME = [70,000ME-1,000 (p)] - [- 10,000ME + 1,000 (p)] \! \,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e2bb12b9eab2a211dd7afc20347274d705fdaafa)