Eliminative materialism

The eliminative materialism or eliminativism is a view within the philosophy of mind . His central thesis is that mental states are appearances. A neuroscientific or cognitive scientific description of humans relativizes everyday psychology accordingly.

The development of eliminative materialism

Eliminative materialism was first developed in the 1960s and stands in sharp contrast to classical positions in philosophy of mind. Even René Descartes , who formulated a philosophy of methodical doubt, considered the existence of the mental inner world to be certain . Only CD Broad briefly considered the possibility of eliminative materialism in his 1925 work The Mind and its Place in Nature , but rejected it as implausible.

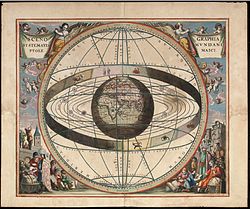

The development of eliminative materialism stands in close connection with the beginning of the history of science seen in the philosophy of science , as described by Thomas Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend was initiated. One result of this new perspective was the realization that scientific progress often does not take place through reductions , as assumed in the positivist models . The history of science shows that the old theories often cannot be traced back to the new theories, but this does not mean that contradicting theories will coexist in the long term. Rather, the old theories are simply given up entirely or their refutations are recognized. Examples are the abandonment of the geocentric world view , the phlogiston theory, vitalism or belief in witches . The thesis of the eliminative materialists is that the everyday theory of mental states will equally prove to be wrong. It is characterized by outdated Cartesian prejudices and completely incompatible with the more recent findings of brain research .

Early formulations of eliminative materialism come from Richard Rorty and Paul Feyerabend . However, these approaches remained outsider positions based on more general considerations about the change in theories. This situation changed in the 1980s with the work of Paul Churchland , Patricia Churchland and Stephen Stich . These three philosophers based eliminative approaches on neuroscientific and cognitive science results.

Some critics view eliminativism as a threatening theory that can have dire effects. Jerry Fodor explains, for example:

- “ If commonsense psychology were to collapse, that would be, beyond comparison, the greatest intellectual catastrophe in the history of our species [...]. "German:" If everyday psychology were to collapse, it would be by far the greatest intellectual catastrophe our species has experienced. "

In contrast, eliminativists consider their thesis to be more welcome. They argue that a neuroscientific vocabulary will lead to a better understanding of people and their problems. They also see themselves confirmed by the experience that the meanwhile considerable number of people with a neurologically based view of the world and self appear to the outside just as inconspicuous as, for example, non-religious people in a traditionally religious cultural community.

Arguments for eliminative materialism

The theory argument

The starting point of all eliminative positions is the thesis that the conventional conception of mental states is a theory that - like any other theory - is fundamentally falsifiable . This theory is commonly referred to in the literature as folk psychology or everyday psychology .

The Churchlands in particular have developed various arguments to show that everyday psychology is a false theory and is ready to be abolished. They argue that many phenomena cannot be explained by everyday psychology that modern neurosciences could investigate and explain. Examples are mental illness , learning processes or memory skills . In addition, everyday psychology has not developed substantially over the past 2500 years and has therefore been a theory that has stagnated for millennia . After all, the ancient Greeks would have had everyday psychology on a comparable level. In contrast, the neurosciences are a rapidly developing scientific complex that can already explain many cognitive abilities to which everyday psychology has no access.

Basically, according to the Churchlands, everyday psychology has been on the decline even since the first scientific developments: In the earliest societies, attempts were made to explain all natural phenomena with the attribution of mental states: the sea was angry, the sun tired. Gradually, these everyday psychological explanations were replaced by more efficient, scientific descriptions. There is no reason to stop in front of our brain and not to accept a more powerful, scientific description of cognitive abilities. If we had such an explanation, we would not need an explanation of behavior in everyday psychology any more than a corresponding explanation of marine behavior . Both represent atavistic thinking.

Two types of objections are raised by critics against the theoretical argument. On the one hand, it is argued that everyday psychology is a thoroughly successful theory. On the other hand, it is doubted that the everyday understanding of the mental can be understood as a theory at all. Jerry Fodor is one of those philosophers who have emphatically pointed out the successes of everyday psychology ( Lit .: Fodor, 1987). It enables communication in everyday life in a very effective way ; Appointments, plans, etc. could be carried out in just a few words. Such effectiveness can never be achieved with complex neuroscientific terminology . Another Churchlands argument was that everyday psychology could not explain phenomena such as mental illness or many memory processes. This argument is countered by critics that it is not the task of everyday psychology to explain these phenomena. It is therefore a mix-up of topics when they are accused of these "shortcomings".

Arguments against eliminative materialism

Intuitive reservations

To many critics, the thesis of eliminative materialism seems so obviously wrong that any further argument is superfluous. You just have to honestly ask yourself to know that you have mental states. Eliminative materialists object to such a rejection of their position that intuitions have very often led to completely false images of reality . Again, analogies from the history of science offer themselves here : It may seem obvious that the sun rotates around the earth , but for all its apparent obviousness, this idea has nonetheless proven to be wrong. Analog: It may seem obvious that there are also mental states in addition to neural events, and yet this could prove to be wrong.

The incoherence objection

Some critics limit themselves to arguing that eliminative materialism is an implausible position. Others, however, claim that it is incoherent because ultimately it must presuppose what it is trying to deny: If the eliminativist says that there are no mental states, then he must presuppose that his words have meaning, are reasonable and are true. Now the terms “ meaning ”, “ reason ” and “ truth ” are only understandable with reference to intentional , mental states. If there were no convictions in the world, but only neural events, there would also be no meaningful states that are true or justified. However, since the eliminativist ascribes importance to his thesis and considers it true and well-founded, he implicitly presupposes what he is actually denying - mental states.

An eliminativist may - if he accepts one of the premises as an objection - react by arguing that meanings, reasons, and truth can also be explained without mental states, since meaningful states would also occur in the language of machines without them being mental States would be attributed. Only machines have no natural languages, but these are adjusted to them by mental beings. It should also be noted that many words in these languages are not used in the same way. Because the opposite of true is untrue , while the opposite of the word false is the word right . Nevertheless, the words "true" and "false" are used as opposites in all programming languages to this day. In addition, both intended states in the machine are true in the sense of existent, while the intended statements of these states are to be interpreted rather than expected and exceptions - i.e. in accordance with or inappropriately of the goal of a mental being. This is where the fundamental problem of the eliminativists arises: they use their examples without checking their comparability.

Qualia

Another problem for eliminative materialism is stated that humans are experiencing beings, that is, they have qualia . Since qualia are generally viewed as properties of mental states, their existence does not seem to be compatible with eliminativism. In fact, eliminative materialists therefore also reject qualia. Many philosophers, on the other hand, consider qualia eliminativism to be implausible, if not incomprehensible.

The classic formulation of qualia eliminativism comes from Daniel Dennett ( lit .: Dennett 1988). Dennett admits that Qualia's existence seems obvious. Nevertheless, he claims that “qualia” is a theoretical term that is fed by an outdated metaphysics or Cartesian intuitions. A precise analysis shows that the term is inherently full of contradictions and ultimately meaningless. Dennett's argument is mostly countered by saying that while it is likely that one has false beliefs about qualia, this does not prove that qualia does not exist.

Effects on psychology

According to eliminative materialism, we get much further in the explanation and therapy of mental malfunctions if we look for anatomical defects or abnormalities in the brain, for functional disorders of physiology, for biochemical changes in brain metabolism, and for genetic damage or disorders in brain development.

This shows the confusion, pointed out by holistic critics of eliminative materialism, of the symptom of a malfunction with its sometimes social or cultural causes. It is countered that the homeostatic therapy options offered are subject to experience-oriented therapy.

literature

Eliminativist literature

- Paul M. Churchland : Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes . In: Journal of Philosophy . 78, No. 2, February 1981, pp. 67-90. doi : 10.2307 / 2025900 . (To eliminate intentional states)

- Patricia Churchland : Neurophilosophy. Toward a Unified Science of the Mind / Brain. MIT Press, Cambridge / MA 1986, ISBN 0-262-53085-6 (detailed description of eliminativism)

- Daniel Dennett : Quining Qualia. In: Anthony J. Marcel & Edoardo Bisiach: Consciousness in Contemporary Science. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988, ISBN 0-19-852168-5 ; 1992, ISBN 0-19-852237-1 , pp. 42-77 (Classical formulation of qualia eliminativism)

- Paul Feyerabend : Mental Events and the Brain . In: Journal of Philosophy . 60, No. 11, May 23, 1963, pp. 295-296. doi : 10.2307 / 2023030 . (Early formulation of eliminativism)

- Richard Rorty : Mind-Body Identity, Privacy and Categories . In: Review of Metaphysics . 19, No. 1, September 1965, pp. 24-54. (Early formulation of eliminativism)

Critical literature on eliminativism

- CD Broad : The Mind and its Place in Nature Routledge & Kegan, London 1925, ISBN 0-415-22552-3 (Broad first considered eliminativism, but rejected it.)

- Jerry Fodor : Psychosemantics: The Problem of Meaning in the Philosophy of Mind , MIT Press, 1987, ISBN 0-262-56052-6 (emphasis on the successes of everyday psychology)

-

Hilary Putnam : Representation and Reality. MIT Press, 1988, ISBN 0-262-66074-1 (eliminativism implausible as it would have to abolish truth)

- German edition: Representation and Reality. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-518-58090-6

Web links

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Entry in the Dictionary of Philosophy of Mind (en)

Individual proof

- ↑ Broad 1925

- ^ Rorty 1965

- ↑ Müller 1965

- ↑ Fodor 1987, p. Xii

- ^ Daniel Dennett : Consciousness Explained. Little, Brown & Company, Boston 1991, Chapter 13: The Reality of Selves , Subsection 3: The Unbearable Lightness of Being. ISBN 0-316-18066-1 , pp. 426-430.