Erwin Rosen

Erwin Carlé ( pseudonym Erwin Rosen ; born June 7, 1876 in Karlsruhe , † February 21, 1923 in Hamburg ) was a German writer and journalist . He was best known for his memory books, in which he reports on his adventures in America and his time in the Foreign Legion. His numerous short humoresques, which appeared in the feature sections of magazines and in collections, were also popular.

life and work

youth

Erwin Carlé alias Rosen was born in Karlsruhe on June 7, 1876. He grew up in Munich, where he attended the Königlich Bayerische Maximiliansgymnasium , until he was expelled from school in 1892 for insubordination. His parents sent him to the Royal Seminary in Burghausen , where he was first placed in a boarding school and then as a city student. When it became apparent that the 18-year-old sub-prime man was flirting with a commoner's daughter, he was expelled for the second time. His parents now sent him to a private school ("Presse"), but he hung around pubs and ran into "grotesque debts". Since the young man did not seem capable of any improvement, his parents took a measure in 1894 that was not so rare in middle-class circles at the time. They forced their 19-year-old son to emigrate to America in order to develop into a full member of civil society.

America

Erwin Rosen's father provided his son with a spare penny and accompanied him to Bremerhaven, from where a ship took him via New York to Galveston in Texas. The young emigrant accepted the adventurous life in the USA with joy despite all adversities. In the three years from 1894 to 1897 he was a cotton picker, pharmacy assistant, railroad tramp and casual worker, boiler cleaner, translator for a German newspaper in St. Louis, fish picker, German teacher and reporter in San Francisco. He wrote down his experiences during this time in the first volume of his American memoirs “The German rascal in America”.

In 1898, out of a thirst for adventure, he took part in the Spanish-American War in Cuba as an American telecommunications soldier, which he survived intact. Towards the end of the war he contracted a dangerous yellow fever and had to undergo quarantine and a four-month convalescence stay in Washington. He recorded his war adventures in the second volume of his American Memoirs. After his recovery, he was seconded to the Communications Department of the US War Department in Washington in 1899.

In the course of the year he entered the army for his departure. He went to New York, where he worked as a freelance reporter and article writer for a year. After his father had died in the meantime, he received a letter from his mother around 1901 “with gloomy news of worries and changed circumstances, and once it said - 'If only we had you here!'” He was in New Orleans and made a decision Made a spontaneous decision to end his American adventure and return to Germany. This is the end of the third volume of his American memories.

return

Erwin Rosen returned to his mother in Munich in 1901. He did not succeed in gaining a foothold in German newspapers until he discovered a niche in the market: "small, short, brisk stories full of action and tension", preferably soaked with humor. He retired to his mother's birthplace in Ulm and wrote 80 stories in three months (see #Yankeegeschichten ), which he was able to sell to various newspapers and which brought him around 100 marks a month, which corresponds to around 650 euros.

An earlier blind application to a major Berlin newspaper was unsuccessful. But after the newspaper saw and printed several of his stories, he was asked to join the newspaper's local office. He was supposed to bring a breath of fresh air to the newspaper, which was under strong pressure from a competitor, with “American smack”. He had to “push through” his lively articles, which were often based on unconventional interviews, against the opposition of his conservative colleagues. He piled up debt after debt, became unsustainable for his newspaper, and eventually had to quit his job.

Around 1903 Erwin Rosen went to London, where he could not gain a foothold as a newspaper man. He returned to Germany and settled in Hamburg. After a while of aimlessness, he got to know and love a woman. Love gave him a boost and he managed to get hired as an editor for a Hamburg newspaper. He made good money, but his old illness of getting into debt caught up with him again. After all, according to today's monetary value, he was in the chalk with usurers with over 40,000 euros. His careless lifestyle led to the fact that the beloved woman "could no longer believe in him". The relationship broke up and Erwin Rosen, in desperation, decided to join the French Foreign Legion .

Foreign Legion

Erwin Rosen went to Belfort in Alsace, where he joined the Foreign Legion on October 5, 1905. In Sidi bel Abbès in Algeria he was accepted into the Legion's First Regiment under number 17889. His romantic ideas about the Legion soon vanished and he only thought about escaping the Legion as quickly as possible. Although he had told no one about his entry into the Legion, he received a letter two years later from his fiancée and a letter from his mother, who had obtained his address from the French War Ministry:

- “One blistering day the Algerian military mail brought a letter for me too. Love found me. I read and read and read again ... In this hour the dead happiness awoke to greater and deeper and more powerful being. "

Thanks to a money transfer from his mother in 1907, he made the dangerous escape by train and ship to Marseille and from there to Innsbruck.

Story writer

After his escape from the Foreign Legion, Erwin Rosen did not want to settle down comfortably in Munich with his mother, but chose Innsbruck in Tyrol as a retreat, where he had once been with his father as a little boy. Here, as in Ulm, he wanted to produce humoresques as a wage clerk in order to pay off the high debts with his Hamburg creditors.

Later he wrote about this time: "I was a money smearer, a line writer, a peddler in the newspaper country, a humoresque manufacturer." His stories, which he continuously produced and often exploited, were in great demand and brought him around 700 marks a month, of which he used 600 marks to repay his debts. In later years he boasted that his stories had earned him an average of 1 mark per word with first and second editions, and that for years he had ranked fourth in the hit list of feuilleton writers.

After a year in Innsbruck, he went to Munich, where he arrived for Carnival in 1908. He continued to write his stories and reported for the Munich Latest News about carnival balls and redoubts. A few lucrative jobs for Berlin newspapers enabled him to fully settle his debts. To do this, he went to Hamburg, paid off his creditors - and stayed there for the rest of his life.

He first lived in Ahrensburg near Hamburg in "a garden house". From 1912 to 1922 he lived in the Hamburg district of Eimsbüttel at the addresses Bogenstrasse 66, Bogenstrasse 24, Koopstrasse 4, Koopstrasse 2, Bogenstrasse 24 and Rothenbaumchaussee 181.

Memory books

Up until now Erwin Rosen had only worked for the daily press. In 1908 he received a letter from the Stuttgart publisher Robert Lutz. He had read a sketch by Erwin Rosen about his experiences in the Foreign Legion in the Swabian Merkur and asked if he wanted to write a memoir about the Foreign Legion for the publisher's “memoir library”. Erwin Rosen accepted the offer, among other things because he saw it as his mission to educate the public about the conditions in the Foreign Legion and to prevent young men from giving themselves over to the Legion.

In March 1909 he published his first book "In the Foreign Legion". He named the last chapter of his book after Emile Zola's open letter in the Dreyfus affair " J'accuse " (I accuse), and in it he settled the account of the exploitative, inhuman system of the Legion. His book, which had numerous editions, including censored editions for young people, became the most important source of information about the Legion in school lessons, the press and political debates in Germany. The book was also published in English, Danish and Dutch, but not in French, but was controversially discussed in the French press. In 1914 Erwin Rosen also presented a dramatic adaptation of the subject under the title “Cafard” (madness), a bad play, as he himself later judged.

Erwin Rosen opened the series of his memory books with the Legion Book, but without giving up his lucrative story-writing. From 1911 to 1913 he brought out a volume of his American memoirs "Der deutsche Lausbub in Amerika", which, like his legion book, appeared in the memoirs library of the Robert Lutz publishing house. In the first volume he reported on his adventurous life from 1894 to 1897, in the second volume on his participation in the Spanish-American War in Cuba in 1898 and in the third volume on his work as a journalist from 1899 to 1901.

Collective works

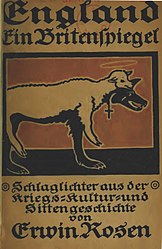

From 1914 to 1916 Erwin Rosen wrote three "War Books" (publisher's advertisement) about the "Great War", about Bismarck and about England, the enemy of the war, for the anecdotes library of the Robert Lutz publishing house.

“A mirror of the prevailing chauvinism that leaves nothing to be desired in terms of clarity,” was the four-volume work “The Great War”, which saw countless editions during the war years. Erwin Rosen published the first volume just two months after the start of the war, and he finished the fourth and last volume in October 1916, when he was already in the field as a soldier. The term “anecdote book” in the subtitle is misleading, in fact it is a collection of the author's reading fruits, which should represent “a faithful painting of the soul of the German people”.

The Bismarck Book and the Britenspiegel were structured similarly and were intended to arm the readers for war and to win them over against the war opponents.

During his time as a deputy officer in the Reserve Infantry Regiment 220, Rosen was slightly wounded in 1917, presumably shortly after his unit was moved from Shchara-Serwetsch (Belarus) to the Western Front in May. He portrays memories of this in "Teufel Geld".

Retirement

In 1920 and 1922 Erwin Rosen presented two more souvenir volumes. In the already mentioned book “Teufel Geld”, he dealt philosophically and anecdotally with the money with which he was at war with all his life. In “Despite all violence” he describes the “life struggles, defeats, job victories of a German writer”, as the subtitle says. The book covers about the years 1901 to 1913. After 1907 he married his wife Käte, the love of his young years, who had called him back with a letter from the Foreign Legion. The marriage resulted in their son Peter, who was born in 1921. Erwin Rosen died on February 21, 1923 at the age of only 46 in Hamburg. From the year he died, 1923 to 1940, his wife Kate appeared in Hamburg's address books and telephone books at Bogenstrasse 24 and later at Koopstrasse 4, where she had previously lived with her husband. She ran a boarding school until 1935.

pseudonym

Before his adventure in the Foreign Legion from 1905 to 1907, Erwin Carlé was employed as editor of a Berlin newspaper. During this time he got into serious debt due to his lavish lifestyle. At a ball he met a lady with whom he had a confidential conversation in a rose arbor. She advised him to write humorous stories again in order to top up his budget. Since he was forbidden to write for other newspapers, his companion advised him to use a pseudonym. In memory of his Saul-Paulus experience in the Rosenlaube, he chose the working name Erwin Rosen, which became naturalized as his author's name. The “flowery of the name”, reminiscent of Jewish family names, earned him scornful posts from anti-Semites who presented him with swastika postcards.

Works

Major works

- Erwin Rosen: In the Foreign Legion: memories and impressions. Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1909, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: In the Foreign Legion. London: Duckworth, 1910, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: The German rascal in America: memories and impressions, part 1, Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1911, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: The German rascal in America: memories and impressions, part 2, Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1912, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: The German rascal in America: memories and impressions, part 3, Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1913, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: Cafard: a drama from the Foreign Legion in 4 acts. Munich: Drei-Masken-Verlag, 1913; Munich: G. Müller, 1914 (first performance Thalia-Theater Hamburg 1914).

- Erwin Rosen: Devil Money: Memories and Impressions. Munich: Rösl, 1920, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: Americans. Leipzig-Gaschwitz: Dürr & Weber, 1920.

- Erwin Rosen: Orgesch. Berlin: August Scherl, 1921.

- Erwin Rosen: In spite of all violence: Life struggles, defeats, job victories of a German writer , Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1922, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: The King of Vagabonds . Hamburg, Gutenberg, 1910 [2. Edition by Schwabe, 1925].

Collective works

- Erwin Rosen (editor): The Great War: A book of anecdotes, 4 parts. Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1914–1916.

- Erwin Rosen (editor): Bismarck, the great German: his size, his strength, his seriousness, his cheerfulness; a book for serious and cheerful hours. Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1915.

- Erwin Rosen: England: a British mirror; Highlights from the history of war, culture and morals. Stuttgart: Verlag Robert Lutz, 1916, pdf .

Yankee stories

- Erwin Rosen: Yankee stories. Leipzig: Reclam, 1910.

- Erwin Rosen: How the worm writhed. In: Arbeiter-Jugend, year 3, 1911, issue 3, pages 41–43, pdf .

- Erwin Rosen: How the barber got his wife and two other Yankee stories. Leipzig: Reclam, 1920, pdf .

literature

- Albert Eichler: Erwin Rosen, England, a British mirror. In: Anglia supplement. Announcements about English language and literature and about English teaching, year 28, 1917, 171–176 (review of #Rosen 1916 ), pdf .

- Thomas Huonker: Revolution, Morals & Art: Eduard Fuchs, Life and Work. Zurich: Limmat-Verlag, 1985, pages 478–479 (About #Rosen 1914 ).

- Walther Killy: Rosen, Erwin. In: Rudolf Vierhaus (editor): German biographical encyclopedia. 8. Poethes - Schlueter. Munich: Saur, 2005, page 529.

- Christian Koller : Criminal romantics in the exotic hell: On the transnational medialization of the French Foreign Legion. In: Saeculum, Volume 62, 2012, Half Volume 2, Pages 247–266, here: 250, online .

- Hedwig Pringsheim ; Cristina Herbst (editor): Diaries: 1911–1916. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2016, pages 354–355 (on a performance of #Rosen 1913.2 in the German Art Theater Berlin on February 24, 1914).

- Arthur Sakheim: Cafard. In: Die Schaubühne, Volume 10, Volume 1, Issue 6, February 5, 1914, page 170 (review of a performance of #Rosen 1913.2 at the Thalia-Theater Hamburg), pdf .

- Rudolf Schmidt: German booksellers, German book printers, Volume 4. Eberswalde: Schmidt, 1907, pages 651-652, online .

Web links

- Literature by and about Erwin Rosen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Erwin Rosen in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Erwin Rosen in the Internet Archive

Footnotes

- ↑ Erwin Rosen gave his age in March 1922 as 45 years ( #Rosen 1922 , page 7). Accordingly, his year of birth is 1876 and not 1873, as stated in #Killy 2005 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1911 , page 5-11.

- ↑ #Rosen 1911 , page 16-18.

- ↑ #Rosen 1911 , page 10.

- ↑ #Rosen 1911 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1912 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1913 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 , page 59th

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 , page 59, 74, 81. - For the conversion of marks into euros see: Deutsche Bundesbank: Purchasing power equivalents of historical amounts in German currencies ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ #Rosen 1909 , page 84-115.

- ↑ Erwin Rosen wrote an article about Isadora Duncan's first visit to Berlin in 1903 ( #Rosen 1922 , pp. 92-93).

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 , pp. 116-183.

- ↑ #Rosen 1909 , page 3.

- ↑ #Rosen 1909 , page 15.

- ↑ #Rosen 1909 , pp. 3, 48, 288–289.

- ↑ #Rosen 1909 , pp. 290–304.

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 , page 202nd

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 , page 218. - 600 marks corresponded to about 3,500 euros. Since he stayed in Innsbruck for about a year, his repayments totaled around 7,000 marks, which corresponds to around 40,000 euros. For the conversion of marks into euros see: Deutsche Bundesbank: Purchasing power equivalents of historical amounts in German currencies .

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 , page 218th

- ↑ #Rosen 1909 , page 254.

- ^ Hamburg address books 1907–1923.

- ↑ #Schmidt 1907 , #Rosen 1922 , page 255.

- ↑ #Koller 2012 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1913.2 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1914.1-4 , #Rosen 1915 , #Rosen 1916 .

- ↑ # Huonker 1985 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1914.1 , page 9.

- ^ German loss lists: 19912 of August 3, 1917. In: Genealogy.net. Computer Genealogy Association, August 27, 2018, accessed on August 27, 2018 .

- ↑ Erwin Rosen: Devil Money . Munich 1920, p. 234-266 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1920 .

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 .

- ↑ Hamburg address books 1923–1940.

- ↑ #Rosen 1922 , pp. 106-108.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rosen, Erwin |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Carlé, Erwin |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German journalist and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 7, 1876 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Karlsruhe |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 21, 1923 |

| Place of death | Hamburg |