Gospel Longum

The Evangelium longum is a liturgical evangelist , which originated around 894 in the monastery of St. Gallen .

The creators were the monks Sintram (calligraphy script) and Tuotilo (binding with carved ivory panels in a wooden box). The Latin gospel pericope book in the format 398 × 235 mm was used to preach the gospel in high mass.

The original evangelist is now in the Abbey Library of St. Gallen and is listed in Codex Sangallensis with Cod. 53. It is one of the permanent exhibits in the abbey library.

It is also accessible in digital form as part of the “ e-codices ” project of the University of Friborg.

history

No other medieval book is known as much as about the Gospel longum. Not only are the client and the artists involved in the production known by name, but the year of creation of the manuscript can also be precisely determined. This is achieved with the help of so-called dendrochronological examinations, in which the date of harvest of a tree is determined based on its annual rings. Such an examination was carried out on the wooden components of the binding in the 1970s. The dating to the year 894 is confirmed by a story written around 1050 about the origin of the Gospel longum in the "St. Gallen monastery stories" ( Casus sancti Galli by Ekkehart IV. ).

The history of the manuscript begins with the two ivory panels over 500 cm 2 that were incorporated into the binding. In the Casus sancti Galli , Ekkehart IV. Comments on the tablets as follows: "But they were former wax tablets for writing, as, according to his biographer, Emperor Karl is supposed to have put them next to his bed when he went to sleep". These tablets, used by Charlemagne as writing pads, probably came to the Erzstuhl of Mainz via the will of Emperor Charles and from there into the hands of Hatto, the then Archbishop of Mainz (891–913). He was supposed to accompany King Arnulf (850-899) to Italy and therefore asked his friend, the St. Gallen Abbot Solomon (890-920), to keep his treasure in trust. Instead of keeping the treasure as promised, Solomon III spread but soon a rumor about Hatto's death and seized the treasure. Most of it he distributed to the poor, he donated a part to the Konstanzer Münster and the rest, including the two ivory tablets, he integrated into the St. Gallen monastery treasure. Then he commissioned his most talented artist, the monk Tuotilo († 913), to decorate the two panels, while the monk Sintram, who was known as an excellent pen, was commissioned to write an evangelist.

As Johannes Duft and Rudolf Schnyder explain, it has long been wrongly assumed that Tuotilo only decorated one of the two panels, as Ekkehart's report states that “one [ diptych ] was beautifully decorated with images; the other was of the finest smoothness, and it was precisely this polished that Solomon gave to our Tuotilo to carve ”. Investigations into the age of the carvings have shown that they come from the same time and by the same hand, namely the Tuotilos.

The Gospel longum, so called because of its unusually high rectangular format, was intended to serve as a splendid evangelist, which was brought out to high-ranking guests on important occasions such as the major church feasts or Advent. Notably, the pericopes that make up the content of the book were made for the cover, not the cover for the book.

description

cover

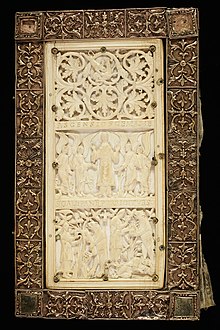

The central element of the binding of the Evangelium longum are the two ivory tablets carved by Tuotilo. Then as now, their size is considered exceptional. Ekkehart writes that the plates are of such a size "as if the elephant equipped with such teeth was a giant compared to its fellow species". Pieces of bone were used to repair holes in ivory.

The front panel of the Evangelium longum (320 × 155 mm, thickness 9 to 12 mm) depicts a “Maiestas Christi”. In the middle, Christ is depicted in the mandorla (almond-shaped halo), in his right hand he holds the book of life. An alpha and an omega are carved on either side of his head. Two seraphim and lighthouses with fire torches flank Christ. The evangelists (John, Matthew, Mark and Luke) are shown in the corners of the picture , while their respective symbols (eagle, winged person, lion and bull) are located directly around Christ. According to Anton von Euw, the four evangelists, the "Quadriga Virtutum" from the theory of virtue Alcuin is on which man is to soar to heaven's throne. Finally, on the upper edge of the picture are the sun and moon, personified by Sol and Luna , and on the lower ocean and earth, represented as Oceanus and Tellus mater . The narrative picture field in the middle of the panel is framed above and below by ornamental areas that are separated by two bars. The following inscription can be found on the walkways: HIC RESIDET XPC VIRTVTVM STEMMATE SEPTVS (Here Christ is enthroned surrounded by the wreath of virtues).

The panel on the back (320 × 154 mm, thickness 9 to 10 mm), also known as the "Gallus panel", depicts the Assumption of Mary and the story of Gallus and the bear, the most famous part of the founding legend of St. Gallen. At the top there is an ornamental part on the back of the binding and the three parts are again separated by bars. ASCENSIO S [AN] C [TA] E MARI [A] E (The Ascension of St. Mary) is on the upper footbridge, and S [ANCTVS] GALL [VS] PANE [M] PORRIGIT URSO (St. Gallus reaches bread for the bear).

The two ivory panels are framed by an oak frame with precious metal mounts. The monk Tuotilo was also responsible for creating this frame, decorated with gold and precious stones from Bishop Hatto's treasure. According to the latest findings, the precious metal cladding of the front panel was replaced in the 10th century. This could be related to a story that occurs in Ekkehart's Casus sancti Galli in chapter 74: According to this, a monk in 954 did not want to kiss the gospel longum when receiving his abbot (Abbot Craloh) and instead threw it to him. It fell to the ground and the front was damaged.

Book block

The book block of the Evangelium longum was described by the monk Sintram, of whom Ekkehart says that his "fingers are admired by all the world" and whose "elegant writing impresses with its steadiness". Johannes Duft and Rudolf Schnyder also speak of an "admirable [uniform], astonishingly [calm] and [balanced] hand". The pages, carefully lined with a stylus, were described in the Hartmut minuscule typically used in St. Gallen in the 9th century. Abbot Hartmut (872–883) developed this late Carolingian book minuscule himself in and for St. Gallen. Every sentence in the Evangelium longum begins with a golden capitals , which results in twenty to thirty such capitals per page. On some pages there are also golden initials, two of which, according to Ekkehart, namely the L and C on pages 7 and 11, Abbot Solomon is said to have personally painted and gilded. A closer analysis of the initials, however, reveals that they come from the same hand as the rest of the manuscript, namely from Sintrams. As Anton von Euw notes, Ekkehart's comment must be seen as a “glory” in favor of Abbot Solomon.

If you include the two mirror sheets glued to the front and the back cover and the two end sheets, the volume consists of 154 parchment sheets. These were paginated around 1800 by St. Gallen monastery librarian Ildefons von Arx from the first flyleaf in Arabic numerals (1–304) using red pencil. The average size of a page is 395 × 230 mm, the text area measures 275 × 145/165 mm and each page of text comprises 29 lines.

content

The Gospel longum contains the Latin gospel pericopes that the deacon had to sing in the solemn high mass. Pages 6 and 7 are adorned with two great initials: On page 6 there is the initial "I" painted in gold and silver and the capital letters IN EXPORTV S [AN] C [TA] E GENITRICIS D [EI] MARIAE. Page 7 shows the capitals INITIV [M] S [AN] C [T] I EUANG [ELII] SE [CVN] D [V] M MATHEV [M] and LIBER GENERATIONIS IHV XPI in sparkling gold.

Up to page 10, the Gospel longum reproduces the first chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, including the family tree of Jesus and the record of his birth from the Virgin Mary. Page 10 forms with the initials "I" and "C" and the capitals INCIPIVNT LECTIONES EVANGELIOR [VM] PER ANNI CIRCVLVM LEGENDAE the beginning of a new part: On pages 11 to 233 follow the pericopes taken from the Gospels for the so-called temporal , thus for the feasts of the Lord as well as for the Sundays with Wednesday and Friday of the whole church year. A small appendix also contains pericopes for Trinity Sunday and for the votive masses on the weekdays from Monday to Saturday.

On page 234 there is the initium for the second part of the Evangelium longum: INCIPIVNT LECTIONES EVANGELIOR [VM] DE SINGVLIS FESTIVITATIBVS S [AN] C [T] ORVM. Pages 234 to 290 contain the so-called Sanctorale , that is, pericopes for the holy festivals of the church year.

Later history and meaning

Today the interior of the manuscript is still in astonishingly good condition, which, according to Anton von Euw, suggests that it was never or only rarely opened. In contrast, Duft and Schnyder note that the cover of the Evangelium longum has undergone at least two restorations. Before 1461, the frets of the book block were renewed and the spine replaced, and the gold bands on the front cover were also mended. The second intervention took place in the 18th century, when the spine and the front gold frames were renovated again.

Several factors make the Evangelistary stored in St. Gallen unique. First of all, the Gospel longum was undoubtedly intended to create not just a book, but a “splendid evangelist”. Ekkehart writes that this is a book of the Gospels, “in the same way, in our opinion, it will no longer exist”.

Apart from the material value of the Gospel longum, it is also one of the manuscripts with the most detailed documented genesis (before 900 until today), which makes it a work of the highest documentary value.

Finally, according to David Ganz, the Gospel longum symbolizes the connection between the St. Gallen monastery chronicle and the court of Emperor Charlemagne as well as the close bond between the monastery and the Archdiocese of Mainz.

literature

- Fragrance, Johannes and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984.

- Ganz, David: Book garments: splendid bindings in the Middle Ages . Reimer, Berlin 2015.

- Schmuki, Karl, Peter Ochsenbein and Cornel Dora: Hundreds of treasures from the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 1998.

- Von Euw, Anton: St. Gallen book art from the 8th to the end of the 11th century . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2008.

Web links

- Evangelium longum in the St. Gallen Abbey Library

- St. Gallen, Abbey Library, Cod. Sang. 53: Evangelium longum (Evangelistary)

Individual evidence

- ↑ e-codices - Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland. In: e-codices. Christoph Flüeler, 2005, accessed on December 12, 2019 (English).

- ^ Karl Schmuki, Peter Ochsenbein, and Cornel Dora: Hundred Treasures from the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 1998, p. 94 .

- ^ Anton von Euw: The St. Gallen book art from the 8th to the end of the 11th century . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2008, p. 156 .

- ↑ David Ganz: Book Garments: Magnificent Binding in the Middle Ages . Reimer, Berlin 2015, p. 259-264 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 22 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 25 .

- ↑ David Ganz: Book Garments: Magnificent Binding in the Middle Ages . Reimer, Berlin 2015, p. 259 .

- ↑ David Ganz: Book Garments: Magnificent Binding in the Middle Ages . Reimer, Berlin 2015, p. 264 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 62 .

- ^ Anton von Euw: The St. Gallen book art from the 8th to the end of the 11th century . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2008, p. 159 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 63 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 61 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 57-58 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 57 .

- ^ Karl Schmuki, Peter Ochsenbein, and Cornel Dora: Hundred Treasures from the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 1998, p. 94 .

- ^ Anton von Euw: The St. Gallen book art from the 8th to the end of the 11th century . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2008, p. 167 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 55 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 55-56 .

- ^ Anton von Euw: The St. Gallen book art from the 8th to the end of the 11th century . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2008, p. 165 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 90-92 .

- ↑ David Ganz: Book Garments: Magnificent Binding in the Middle Ages . Reimer, Berlin 2015, p. 259 .

- ^ Anton von Euw: The St. Gallen book art from the 8th to the end of the 11th century . Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2008, p. 163 .

- ↑ Johannes Duft, and Rudolf Schnyder: The ivory bindings of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984, p. 93 .

- ↑ David Ganz: Book Garments: Magnificent Binding in the Middle Ages . Reimer, Berlin 2015, p. 285 .