Fairness doctrine

The Fairness Doctrine was a regulation in existence in 1949 by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the regulatory and licensing authority for broadcasting and communications in the United States . It stipulated that licensees in the field of broadcasting were required to present controversial issues of public interest in an "honest and (between the various viewpoints) equal and balanced manner" when reporting on controversial issues. The doctrine was highly controversial and a point of contention in legal disputes several times during its validity. In 1987 it was revoked by the FCC.

history

Origin and judicial confirmation

The fairness doctrine resulted from the mandate contained in the Radio Act of 1927 to the FCC's predecessor Federal Radio Commission (FRC) to structure the granting of broadcasting licenses in such a way that the licensees should serve the benefit, interest and needs of the public. The resulting licensing practice of requiring broadcasters to show due respect for the opinions of others was finally formulated in 1949 in a formal FCC rule, henceforth referred to as the Fairness Doctrine. Ten years later this was made mandatory by an amendment to the Communications Act of 1934. To this end, the law was supplemented with the following wording:

"A broadcast licensee shall afford reasonable opportunity for discussion of conflicting views on matters of public importance."

"A broadcast licensee should provide a reasonable amount of opportunity to discuss opposing viewpoints on issues of public interest."

On the one hand, this represented a fundamental obligation for radio and television broadcasters to include appropriate topics in the program in the form of reports, information programs, debates and similar broadcast formats. On the other hand, it also emerged from this formulation that the various points of view should be presented in a balanced manner when presenting these topics. However , this rule did not apply to the cable networks that emerged later and the programs based on them, as these are privately financed and operated and do not use a commons comparable to the public frequency spectrum.

The most important court ruling on the legitimacy of the fairness doctrine was the 1969 Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC (395 US 367, 1969) of the United States Supreme Court . In this judgment, the court ruled that this provision was constitutional and therefore does not violate the 1st Amendment to the United States Constitution, which among other things guarantees freedom of expression and freedom of the press :

"[...] A license permits broadcasting, but the licensee has no constitutional right to be the one who holds the license or to monopolize a [...] frequency to the exclusion of his fellow citizens. There is nothing in the First Amendment which prevents the Government from requiring a licensee to share his frequency with others. [...] It is the right of the viewers and listeners, not the right of the broadcasters, which is paramount. [...] ”

“[...] A license is a broadcasting license, but the licensee has no constitutional right to own the license or [...] to monopolize a frequency in such a way that its fellow citizens are excluded. Nothing in the First Amendment prevents the government from obliging a licensee to allow others to participate in its frequency. […] It is the rights of viewers and listeners, not those of the broadcasters, that have priority (in this regard). [...] "

Although comparable regulations for newspapers had been classified as unconstitutional, due to the limited technical availability of the radio wave frequency spectrum , the court considered state regulation of programming for the broadcasting sector on public frequencies to be lawful. Nonetheless, the court found that constitutionality would have to be re-examined if the doctrine restricted freedom of speech. Based on this decision, compliance with the fairness doctrine was considered to be the most important prerequisite for operating a radio station in the public frequency range in the following years. In 1974 the court came up with another ruling, Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (418 US 241, 1974), to the conclusion that the fairness doctrine would “inevitably limit the strength and diversity of public debate” (“... inescapably dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate ... "). However, this judgment did not include a reassessment of their constitutionality.

However, the fairness doctrine did not mean that every single program should be balanced in terms of content, or that opposing viewpoints should be given the same broadcasting time. It was only intended to prevent unilateral programming for broadcasters on public frequencies. In practice, most of the time, the radio and television stations concerned made the appropriate airtime available when a one-sided report was broadcast, either voluntarily or on the basis of inquiries and complaints from the other side. Effective compliance also depended on the attention of the listener or audience.

Controversy and abolition

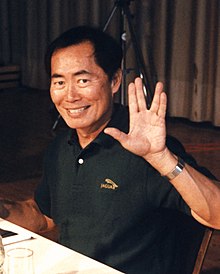

In the late 1960s, American attorney John Banzhaf won a lawsuit on the application of the fairness doctrine to television advertising for tobacco products , as a result of which the FCC announced that it would rigorously enforce this decision. The resulting broadcast of television campaigns against smoking, for example with the participation of actor William Talman , who had lung cancer , first led to the tobacco industry's voluntary renunciation of television advertising for its products and, at the beginning of 1971, to a corresponding statutory one due to the negative publicity for the tobacco industry Prohibition. A rather curious decision in connection with the doctrine came when actor George Takei, known from the television series Star Trek , ran for a seat on the Los Angeles City Council in 1973 . With reference to the fairness doctrine, his opponent demanded that the local television stations either have free airtime for his election advertising to the same extent as the Star Trek episodes that were broadcast, or that they be canceled for the duration of the election campaign. However, the corresponding lawsuit was dismissed by the Los Angeles courts.

Throughout the existence of the fairness doctrine, only one broadcaster license has been revoked by the FCC for continued non-compliance. In the early 1980s, the FCC began to withdraw parts of the doctrine or to fail to enforce it. The main reason for this was the efforts of the administration of then US President Ronald Reagan to deregulate and reduce state control in various social and economic areas. In the area of broadcasting, the FCC believed that radio and television broadcasters were not representatives of the public ( community trustees ) with corresponding special obligations, but merely participants in the media market. In 1985 the agency publicly announced that the fairness doctrine was not in the public interest and was a violation of the First Amendment. A year later, the District of Columbia Court of Appeals upheld the legality of the FCC's widespread non-effective enforcement.

In August 1987, the FCC unanimously abolished the fairness doctrine, justifying this step by stating that, given the wide availability of various media, the provision hindered rather than promoted public debate. The amendment to the Communications Act , introduced in 1959, was interpreted in accordance with the previous court decision merely as an opportunity for the FCC to enforce the stated obligations at its own discretion, but not as a mandatory task of the FCC. With this view, no change to the law was necessary to suspend the fairness doctrine. In the fall of the same year, Congress attempted to reverse the FCC's decision by passing federal law, but failed due to a veto by President Ronald Reagan despite clear majority decisions by the Senate and the House of Representatives . Further attempts at restoration in 1989 and 1991 were also unsuccessful after the incumbent President George HW Bush again announced his veto.

Two rules resulting from the doctrine remained in force until 2000 even after they were repealed. The regulation, known as the personal attack rule , stated that radio and television stations had to notify a person or group within a week if they had been the target of a personal attack as part of the broadcast program. In addition, the broadcasters had to provide those affected with a recording of the relevant part of the program as well as airtime for a reply. The same applied due to the rule known as the political editorial rule when a broadcaster expressly supported or rejected a certain candidate for political office in the context of an editorial . In this case, too, the opposing candidate was entitled to notification and airtime for his own statement. The District of Columbia Court of Appeal has asked the FCC to justify these rules from the standpoint of repealing the doctrine of fairness. Instead of a justification, the authority also repealed these two regulations in 2000.

Several senators from the left wing of the Democratic Party, as well as independent Senator Bernie Sanders , who is considered the first and so far only avowed socialist senator in United States history, have publicly announced their support for a reversal of the FCC decision of 1987 for a reinstatement to achieve the fairness doctrine. On the other hand, the doctrine has been regularly criticized and rejected by conservative politicians and commentators because, in their opinion, it prevents their views from being represented in the media.

literature

- Fred W. Friendly: The good guys, the bad guys, and the first amendment: Free speech vs. fairness in broadcasting. Random House, 1976, ISBN 0-39-449725-2

- Larry D. Benson: The Fairness Doctrine: A Bibliography. Vance Bibliographies, 1990, ISBN 0-79-200429-9

- Brian Fitzpatrick: Unmasking the Myths Behind the Fairness Doctrine. Media Research Center, 2008 ( PDF file , 30 pages; approx. 2.58 MB)

Web links

- Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC full text of Decision 395 US 367, 1969

- The Museum of Broadcast Communications - Fairness Doctrine (English)