Rock paintings in the highlands of Sjunik

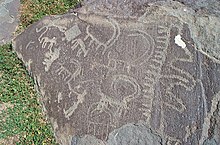

In the highlands of the Armenian province of Sjunik are located at an altitude of 2800 to 3300 m above sea level. NN in many places rock art from prehistoric times. They were once worked into boulders of volcanic origin ( petroglyphs ). Most often animals are depicted on them that are hunted or kept as farm animals. Goats are shown particularly often, but more rarely deer, big cats and other animals. There are also human figures. Some of them are shown dancing, hunting or fighting in small scenes. Some of these figures could show shamans or even gods. Archaeologists assume that the images were part of mythical and spiritual ideas and rituals of the early highland inhabitants, for whom the goat was a central part. The large number of rock carvings and their widespread distribution suggest that they were created over centuries. An exact dating of the rock paintings is not possible to this day. At least some of the depictions refer to the Bronze Age . But some pictures can be even older. So far, the particularly extensive collections of rock art at the former volcanoes Ughtasar (Tskhouk), Naseli and Sepasar have been scientifically examined. They are part of the rock art that can be found everywhere in the highlands of Armenia and also beyond the national borders.

The Ughtasar rock art

Widespread around a small lake in the caldera of the extinct volcano Ughtasar (or Tskhouk) ( 39 ° 41 ′ 10 ″ N , 46 ° 3 ′ 5 ″ E ) are located at an altitude of 3300 m above sea level. NN numerous rock paintings on stone blocks. At the beginning of the 20th century, they first attracted the interest of some researchers. In 1967 and 1968 the Armenian archaeologists Karakhanian and Safian examined the images together with comparable rock art near Jermajur in Nagorno-Karabakh . On the joint website of HaykNet and ArcaLe, 342 sketches of these rock art are put online. Since the rock art was published in 1970, Ughtasar has been the most prominent place of Armenian rock art and now also attracts tourists.

In 2009, an Armenian-British research team in collaboration with the Landscape Research Center in Great Britain was commissioned to re-record and evaluate the entire inventory of rock art in the caldera. The main goal was to better understand what significance this place had for the creators of rock art and what they used it for. For five years, the employees of this team worked there in the summer months. They measured the area, systematically recorded all the processed boulders, photographed them and documented their location and relationship to other blocks. They also recorded the other superficially visible archaeological traces and finds. Stereo and 'structure of motio' photogrammetry as well as multispectral methods were used for particularly interesting objects .

Accordingly, motifs such as animals, people and, very rarely, wagons and objects were found in the entire study area on a total of almost 1,000 stone blocks. Up to a dozen individual motifs can be incorporated into one stone. By far the most popular motif was the goat; 65% of the motifs found are goats (or ibex). These are stylistically greatly simplified and shown with exaggeratedly large horns. 16% of the motifs show people and almost 7% big cats. Wavy lines or snakes, deer, bulls and dogs appear less frequently. The dominance of goat pictures has led to the fact that the stones are called “Itsagir” - “goat letters” among the population.

People appear four times less often than goats in the representations. Some of them have unusually large hands. Others are shown in small scenes, hunting animals with a bow and arrow , dancing or fighting against each other. Some are also shown closely related to goats. These scenes support the archaeologists' hypothesis that at least some of the rock art had a function in “ shamanic ” rituals. The goat pictures could have been used as protectors or aids in spiritual activities. The rock carvings of Ughtasar are in this respect comparable with the rock carvings of other parts of the Caucasus and Central Asia .

Although the rock carvings are present in many places in the caldera, they are clearly visible and easily accessible on the edge of the rock dump and especially north of the glacial lake. An almost as high concentration of rock art can also be found at the southern entrance of the caldera. There the visitors are "greeted" by a collection of clearly visible and extensive rock art. More details on the work and the preliminary research results of the Armenian-British team are published on the Ughtasar Rock Art Project website.

The rock art by Naseli and Sepasar

In 2011 archaeologists discovered two more rock dumps with numerous rock carvings on the slopes of the former volcanoes Naseli and Sepasar during a site survey of the Armenian highlands. A German-Armenian research team from the University of Halle-Wittenberg , in cooperation with the Institute for Archeology and Ethnography of the Armenian Academy of Sciences, was commissioned to research the newly discovered rock art regions. The aim was a quick inventory of all rock art and their location in the area so that a digital database can be created with all rock art in the region. This should enable a deeper understanding of the rock art and an assessment of its state of preservation.

The first rock dump is about 2900 m above sea level. NN on the southern foot of the mountain Naseli ( 39 ° 42 '40 " N , 46 ° 0' 0" O ). It has an extension of 800 m × 100 m and runs in an east-west direction. The second rock dump is located at an altitude of 3200 m on Sepasar Mountain and has an extension of 250 m × 230 m ( 39 ° 42 ′ 35 ″ N , 46 ° 2 ′ 35 ″ E ). The two investigation areas were not limited to these two block heaps, but were considerably expanded during the investigation so that three times as much area could be searched for rock art. First a remote-controlled quadrocopter was used, which photographed the investigation areas from the air. The resulting images were merged into a digital aerial map using georeferencing . Then the rock paintings visible in the aerial photographs were sought out, photographed from close up and drawn. In addition, the environment, orientation, patina formation and state of preservation of each stone were recorded in writing.

With this quick process, around 3500 processed stone blocks with around 11000 individual motifs could be documented between 2012 and 2014. As with the Ughtasar rock carvings, the goat is most often depicted here by a large margin. Nevertheless, with around a third of the figures, the goat is only half as common as on Ughtasar. It is often not possible to clearly determine whether the goats are domesticated or wild. Some of these figures could show the wild Bezoar goat , a prey for hunters and big cats. Other animal species such as big cats ( cheetahs and snow leopards ), deer and bears were shown less often. With 8% of the figures, people are represented four times less often than goats. They are armed with lances, bows and arrows, with arms raised or with unusually large hands and feet. The 30 or so illustrations of two and four-wheeled chariots, which are often pulled by bulls, are unusual. Despite the abundance of pictures, only a few scenic representations were found, mostly hunting scenes.

As with the Ughtasar rock art, the images pile up on the easily accessible edges of the rock dumps. Here, too, the images occur more frequently near water bodies, especially in the riverbeds of the meltwater rivers, which carry little or no water with them in the summer months. Individual collections of rock carvings could be identified that are thematically coordinated with one another or even together form a place of worship . A final assessment of the function of the rock paintings and their relationships to one another is not yet possible, as the analysis of the collected data is still being worked on. The final research results should be available in 2019.

The creation of the rock art

The southern Caucasus was exposed to strong volcanism in the Pliocene and Pleistocene . Numerous lava flows , especially from crevice eruptions , solidified on the mountain slopes and in the craters of the volcanoes. In the last Ice Age , the lava rock was smoothed by glaciers that moved over it. Glacier erosion ensured that a dark, shiny iron-manganese patina formed on the stone blocks , the lava rock disintegrated into stone blocks and the blocks were pushed together to form what is now the dump. The patina on the boulders can take on different colors from red-brown (with a high iron content) to blue-black (with a high manganese content).

After the end of the last ice age around 12,000 years ago, the glaciers in the southern Caucasus disappeared and grass pastures expanded in the former volcanic landscape, so that livestock farming was still possible in the summer months at an altitude of 3000 meters above sea level . To the herdsmen and hunters who stayed at regular intervals in the high mountains thousands of years ago, the smooth, shiny stone blocks seemed to have been made to perpetuate something that was important to them. With hard, pointed tools, perhaps made of basalt, they then worked their motifs into the stones using the pick technique. They broke through the iron-manganese crust on the rocks. The lighter basalt stone under the crust that became visible as a result made the picked motifs stand out in an optically effective manner.

On some rock paintings in the highlands it can be clearly seen that individual motifs, but also names and insignia, were only picked or scratched into the boulders in the last few decades. Obviously, between the 1950s and 1980s, cattle herders immortalized themselves on the stones, as your colleagues did in a similar way thousands of years ago. These rock art partially overlay the older rock art. However, the rock art is even more endangered by ongoing erosion and tourism. A large part of the very fragile iron-manganese crust on many boulders has flaked off, which has already destroyed some rock art. To protect the images, Armenia has meanwhile placed the entire highland region under monument protection and intends to apply for World Heritage status for the rock art.

The age of the rock art

Determining the age of the rock art is an open question in archeology. On the basis of a series of evidence, archaeologists believe it is likely that the majority of the rock art in the period from the 5th to the 1st millennium BC. Was created. The time period cannot be narrowed down more precisely, because a direct method of determining the age of petroglyphs does not yet exist. The differently strong patina formation at the picked areas of the rock art could, however, allow a chronological classification in the future, at least it enables a differentiation between older and younger rock art.

Temporal classifications can only be made indirectly:

1. On the basis of the image motifs: The carts on carts of oxen shown did not exist before the 4th millennium BC. Occasional spoked wheels on these cars are only known from the Bronze Age.

2. Based on the findings: An obsidian blade found in the caldera of Ughtasar points stylistically to the Copper Age or the beginning of the 4th millennium BC. Chr. A pottery shard found right next to a rock painting was dated to the early Bronze Age (4th - 3rd millennium BC).

3. On the basis of stylistic comparisons with representations on other archaeological finds: Images on Middle Bronze Age ceramics from Armenia show similar animal representations, in some cases even incorporated with the same picking technique as the rock art.

4. Using a comparison with rock carvings from other regions: Almost identical rock carvings from the Vorotan , Nakhichevan and Nagorno-Karabakh rivers refer to this epoch due to their proximity to early Bronze Age settlements.

A revealing discovery was made at the volcanoes of the Karkar Group, which include the Naseli volcano. There, the lava flow from the latest volcanic eruption overlays a rock painting. The rock from this lava flow was also used in the construction of a nearby barrow, the inventory of which can be traced back to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC using the C14 method . Could date. This proves that some of the rock art in the Sjunik highlands is older than this grave.

Picture gallery

literature

- GH Karakhanian, PG Safian: The Rock-Carvings of Syunik (= The Archaeological Monuments and Specimens of Armenia. Volume 4). Yerevan 1970.

- Franziska Knoll : Petroglyphs in the Syunik Highlands (Armenia). Mapping (pre-) historic traces. In: Adorants. 2016 (2017), pp. 73-83 ( online ).

- Franziska Knoll et al .: The rock art in the highlands of Sjunik. In: Archeology in Armenia II. Results of the cooperation projects 2011 and 2012 as well as selected individual studies (= publications of the State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt. Volume 67). State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt, Halle (Saale) 2013, ISBN 978-3-939414-96-4 , pp. 209-230 ( online ).

- Harald Meller , Franziska Knoll, Veit Dresely: The rock paintings of Ughtasar, Province of Sjunik. In: Archeology in Armenia. Results of the cooperation projects 2010 - A preliminary report (= publications of the State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt. Volume 64). State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt, Halle (Saale) 2011, ISBN 978-3-939414-62-9 , pp. 131–142 ( online ).

- Sandro Hayrapeti Sardaryan: Հայաստանի ժայռապատկերները քարի դարից մինչև բրոնզի դար. = Armenian Petroglyphs from Stone to Bronze Ages. = Наскальные изображения в Аремнии от каменного до бронзового веков. EPH hratarakchʻutʻyun, Yerevan 2010, ISBN 978-5808412026 .

- Samvel M. Shahinyan: Հայկական լեռնաշխարհի ժայռապատկերներն ու հնագույն խորհրդանիշները. = Petroglyphs and ancient symbols of Armenian Highland. Zangak-97, Yerevan 2010.

- Tina Walking, Heather James: Rock carvings in the Syunik Mountains of Southern Armenia. In: PAST. The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society. No. 75, 2013, pp. 14-16 ( online ).

- Tina Walkling, Anna Khechoyan, Ani Danielyan: Seeking the elusive goat: Conspicuous and hidden petroglyphs in a caldera in southern Armenia. In Hipólito Collado Giraldo, José Julio García Arranz (ed.): Symbols in the landscape: Rock art and its context. Proceedings of the XIX International Rock Art Conference IFRAO 2015 (Cáceres, Spain, August 31 - September 4, 2015) (= Arkeos. Volume 37). CEIPHAR, Tomar 2015, ISBN 978-84-9852-463-5 , pp. 1337-1340.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Knoll (1): https://www.academia.edu/5656799/F._Knoll_u._a._Die_Felsbilder_im_Hochland_von_Syunik._In_H._Meller_P._Avetisyan_Hrsg._Arch%C3%A4ologie_in_L_Arandesoff%C3%A4ologie_in_L_Armenff_II% BCr_Denkmalpflege_u._Arch._Sachsen-Anhalt_Landesmus._Vorgesch._67_Halle_Saale_2013_209_230

- ↑ See Karakhanian GH, Safian PG (1970): The Rock-Carvings of Syunik, in "The Archaeological Monuments and Specimens of Armenia" 4, Yerevan

- ^ GH Karakhanian, PG Safian: THE ROCK-CARVINGS OF SYUNIK . HaykNet, ArcaLe. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ↑ See http://www.armenianheritage.org/en/monument/Ughtasar/120

- ↑ See https://content.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/multi-light-imaging-heritage-applications/Multi-light_Imaging_FINAL_low-res.pdf/

- ↑ a b http://ughtasarrockartproject.org/results.html

- ↑ http://ughtasarrockartproject.org/page4.html

- ↑ Walking: http://www.prehistoricsociety.org/files/PAST_75_for_website.pdf , p. 16

- ↑ Knoll (1), p. 211

- ↑ Knoll (1), p. 213 f.

- ↑ a b c Knoll (2): https://www.academia.edu/15837781/F._Knoll_H._Meller_Goats_-_as_far_as_the_eye_can_see._Recording_Rock_Art_in_the_Syunik_highlands_Armenia_._In_F._Troletti_Hrsg._Proceedings_of_the_XXVI_Valcamonica_Symposium_September_9_to_12_2015_Capo_di_Ponte_2015_153_158 , p 2

- ↑ See Knoll (3): https://www.academia.edu/33418412/F._Knoll_Petroglyphs_in_the_Syunik_Highlands_Armenia_._Mapping_pre-_historic_traces._Adoranten_2016_2017_73_83 , pp. 75–77

- ↑ Knoll (1), p. 224 f.

- ↑ See Knoll (3), p. 82

- ↑ Meliksetian: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Khachatur_Meliksetian/publication/257614699_Pliocene-Quaternary_volcanism_of_the_Syunik_upland_Armenia/links/00b495257ed878ecbb000000.pdf , p. 250

- ↑ Knoll (1), p. 214

- ↑ a b http://ughtasarrockartproject.org/page13.html

- ↑ Knoll (3), pp. 79-81

- ↑ a b Knoll (1), p. 226 ff.

- ↑ Knoll (1), p. 228