myth

A myth ( masculine , from ancient Greek μῦθος , " sound , word , speech , story , legendary story, fairy tale ", Latin mythus ; plural : myths) is a story in its original meaning. In religious myth, human existence is linked to the world of gods or spirits.

Myths lay claim to validity for the truth they claim. Criticism of this claim to truth has existed among the pre-Socratics since the Greek Enlightenment (e.g. Xenophanes , around 500 BC). For the sophists , the myth stands in opposition to the logos , which tries to establish the truth of its assertions by means of rational evidence.

In a broader sense, myth also refers to people, things or events of high symbolic importance or simply a wrong idea or lie. For example, the adjective "mythical" is often used in colloquial language as a synonym for "fairytale-vague, fabulous or legendary".

A German version that was used until the end of the 19th century and is rare today is “the myth ” as a singular .

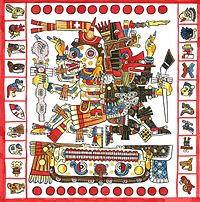

The ensemble of all myths of a people, a culture, a religion is called mythology (from the Greek μυθολογία “saga poetry”). So one speaks z. B. from the mythology of the Greeks , the Romans , the Teutons . (For further meanings of this term, see main article Mythology .)

Conceptual delimitation and features

In the 19th and 20th centuries there are very different definitions. The view that “the” myth exists as a cross-cultural, meaningful narrative style, had numerous followers in the time of neo-humanism . The psychoanalysis or the anthropological school of Claude Lévi-Strauss continued this view into the 20th century. A few years ago, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht tried to trace back what seems to be common to myths to a modern type of observation that seeks to perceive meaning and , in contrast, regards a perception directed at presence as mythical.

Unlike related narrative forms such as sagas , legends , fables or fairy tales , a myth (unless this term is used in its reverse meaning as an ideological trap or story of lies) is considered to be a narrative, identity , overarching explanations, meaning in life and religious orientation as a largely coherent one Kind of world experience conveyed.

In some myths, people interpret themselves, their community or world events in analogy to nature or cosmic forces. Regular processes in nature and the social environment are traced back to divine origins. André Jolles notes that everything that has or should endure must be canonized in its origin. The myth's understanding of time is not based on difference and development, but on unity and cyclical repetition. Beyond historical time, myths are located in a space ruled by numinous forces or personifications .

In terms of content, myths are sometimes divided into cosmogenic or cosmological myths, which thematize the origin and shape of the world, and anthropogenic myths about the creation or origin of man. Likewise, attempts are often made to distinguish between, on the one hand, myths of origin and justification to explain certain rites, customs or institutions and, on the other hand, founding myths about the origin of certain places or cities, historical myths about the early days of a tribe or people, and eschatological myths that refer to the end relate to the world, meet. Such delimitations are difficult to make with complex myth systems. To many myths there are counter-myths that symbolize the downfall of the existing or the struggle of antagonistic forces. But the myth often also thinks of opposites as a unit.

According to an ideal that is often put forward, “original myths” arose in non-scripted cultures and were passed on orally by a selected group of people such as priests, singers or elders. The writing and the subsequent collection and arrangement in genealogies or canonical handbooks are seen variously as signs of a decline in the traditional power of myths.

In non-scripted religions , orally transmitted narratives played a role comparable to that of the holy scriptures in the world religions . Some of them still serve today to transmit and maintain the faith and the values associated with it. It is a matter of dispute whether such narratives can be reconciled with the European concept of myth. As early as 1914, the ethnologist and researcher of the myths of the North and South American indigenous peoples, Franz Boas , advocated using the generic terms of the narrator in addition to the term myth. He saw in the myths on the one hand a cultural mirror of the material and spiritual culture of the peoples he researched, on the other hand stories (folk tales) that spread across wide cultural areas in an often simplified form. Regardless of the attempts to delimit the terms myth and narrative, according to Boas, the elements of both mix in a hardly separable way: the myth emphasizes the ethnic-particular element, insofar as it is an ethnographic autobiography ; history could also wander. This position is also held by Elke Mader, who examines both ancient Indian and modern myths. Hartmut Zinser , on the other hand, sees little in common between the ethnological “theories of myth”. It is now customary in scientific literature to prefix a definition of what is meant when the word myth is used.

Concept history

Antiquity

The idea of authority, higher truth and general relevance (including the suspicion of delusion) is not originally associated with the term myth. The written collection and fixation of myths in Hesiod and Homer , however, already falls into a late stage, in which the myths had lost their original function and were passed on in an aesthetically and poetically distant form. Xenophanes and Hecataeus of Miletus considered myths to be morally reprehensible or ridiculous inventions, while Epicurus radically rejects myths of gods. Since the 5th century BC There were attempts to justify the Homeric myths in particular. Theagenes of Rhegion , who is considered the founder of the allegorical interpretation of Homer, and the Stoa regard the myths of gods as natural legories . So Zeus appeared to her as an allegory of heaven.

- Rationalist critique of myths

In addition, rationalistic interpretations of the myth developed. Euhemeros attributed the myths of the gods to the fact that kings as benefactors of mankind had been deified for their services, as happened in the Hellenistic and later in the Roman rulers' cult. Also Palaephatus led the Greek myths to historical events and relationships back and fell while in rationalistic speculation. So was Europe , the lover of Zeus, has not been abducted by a bull, but by a man named Ταῦρος (bull).

For Poseidonios, on the other hand, the founder of a historical interpretation of myths, fascinated by the Celtic druids , the myths preserve the knowledge of a golden past. The barbaric societies appeared to the Greeks in this time of political and social decline as a reflection of their own past.

- Myth as a literary genre

For Plato , myth can contain truths and falsities; Poets are asked to compose mythoi that are as true as possible . The literary genre of the so-called Platonic myth, on the other hand, can include very different things: a simile , a metaphor or a thought experiment. In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato created a myth of the origin of the world ( cosmogony ), from which essential aspects were received from Neoplatonism to Georg Friedrich Creuzer .

Aristotle only grants a myth the possibility of approaching the truth . By myth he understood the imitation of action , that is, of something in motion, in contrast to the static characters , which in his opinion do not yet constitute poetry. So it would be a myth to speak of a person walking instead of just characterizing his walk. Aristotle saw his text as a kind of instruction manual for poets. For him, myth was a characteristic of a successful tragedy . Aristotle also narrowed down the term myth to the meaning that is still used today, namely the typical Greek myth of gods and heroes.

In Hellenism and Roman antiquity, the myth was increasingly propagated and used as a moral and educational instrument, for example by Dion Chrysostom .

middle Ages

Christianity viewed myth predominantly as a competing pagan theology; but due to a certain tolerance it survived as an educational asset less clergy and poet (as with Dante , with whom enthusiasm and resistance are mixed, with Konrad von Würzburg and in the Carmina Burana ). However, the Christian religion was faced with the task of rendering the Greco-Roman mythology and in particular its world of gods "harmless" by demonizing, euhemerizing or allegorizing moralization. The myths thus fulfilled educational functions similar to those of the Christian legends ; the term myth was no longer used. The courtly medieval world, however, made use of the ancient "novels" for dynastic legitimation and identity formation. An example of this so-called Origo gentis is the Eneasroman by Heinrich von Veldeke .

Snorri Sturluson viewed the Old Norse songs of gods in the light of a late pagan-Christian syncretism, but provided a rationalistic-euhemeristic explanation of the deification of Freyr and Njörd as alleged earlier Swedish kings. Their veneration was evidently based on the fact that they provided their people with prosperity, rich harvests and large livestock, whereby the figures of the benevolent king and the god of fertility merged.

Renaissance and Enlightenment

During the time of Renaissance humanism , when Christianity was still predominant, classical mythology was increasingly received without being taken seriously in the religious sense. The ancient epics became in time to compete with the biblical narratives.

The close connection between myth and inevitable fate that characterized French classical music in the 17th century has to do with the emancipation of ancient myths from biblical narratives. Classical drama dressed modern political issues in the guise of ancient myths. Modern drama theory goes back to the theory of ancient tragedy and its Christian reception: the tragic fate of a hero like Oedipus is predetermined and inevitable. The Christian conceptions of predestination , on the other hand, are based on the continuing possibilities of repentance and forgiving grace , that is, on a fundamental voluntary nature in which good and bad are of course precisely defined. The emphasis on the inevitability of mythical guidelines, including in modern variants of a scientific determinism , such as that expressed in the terms archetype , Oedipus conflict , electra complex or analysis of fate , expresses a tradition of rebellion against Christian moral ideas.

The Enlightenment understood “the” myth as a child's preliminary stage to conceptual thinking and considered it to be overcome. Charles de Brosses rejected the possibility of an allegorical interpretation of the myth and saw in it a product of ignorance; he recognized the alleged original form of pagan religions in the fetishism of myth. For Giambattista Vico it was only an expression of low intellectual power and too much imagination.

In the early enlightenment phase, the ancient materials were also increasingly used for ethical and moral education. Johann Christoph Gottsched translated myth as “ fable ” ( attempt at critical poetry before the Germans , 1730). In this sense, myth could be both the basic structure of a narrated action and the moral doctrine on which a narrative is based. The idea of myth as a moral theory has subsequently replaced the older narrative meaning. The loss of power of the churches at that time called in many eyes a replacement for biblical material that had been robbed of its authority. Traditionally the ancient epics and dramas took on this task. The world of ancient myths created freedom from conservative religious ideas (as it was in the Weimar Classic ).

Romanticism and 19th century

In Romanticism , myth was again not understood as a counter-world to the religious, but as its renewal. Jean Paul regards the turning away from the “earthly present” to the “heavenly future” associated with the devaluation of the physical world as the actual myth of his time and the source of all romantic poetry: Angels, devils and men grow up on the “arson of finitude” Saints and the longing for infinity or infinite bliss. The sensual and cheerful Greek myth is transformed into a “demonology” of physicality.

For most romantics, however, myths were veiled wisdom that came from a figuratively thinking prehistoric age. This poeticization of myth led between 1800 and 1840 to the question of the origin of the mythologies of the world that haunted the romantic poets. In addition to the Greek myths, they increasingly resorted to medieval "Nordic" and later also to Indian mythology , which Friedrich Schlegel regarded as an expression of an ancient religion that was esoterically protected by priests, which outsiders only communicated symbolically and mythically and found themselves in the mysteries of the Greeks have received. The myths summarized the poetic elements of the original language into a view of the world as a whole. In Schelling's philosophy, the myth is no longer conceived by man, but, conversely, man seems to be an instrument of the myth. For Schelling and Schlegel it is no longer philosophy, but poetics in the form of a “new mythology” that is the (above all aesthetic) “teacher of humanity”. Friedrich Creuzer argues in an anti-rationalist way that the myth can only be developed through intuition and experience. It separates the inner side, the theological content, from the outer side that is understandable to the people.

The lost and at the same time invoked authority of myth became an essential theme of the time. Especially in young nations, the reconstruction and collection of national myths became the subject of national romantic poetry (e.g. the Kalevala in Finland ). They did not shy away from fiction (e.g. the Estonian Kalevipoeg ) and falsification (in the case of the alleged Celtic Ossian myth). The exhaustive search for original myths shows the narrowly limited effect of the Enlightenment, which sought to eliminate the myths as forms of priestly wear.

For Karl Marx the myth was the attempt to shape the forces of nature in the imagination, in the form of an artistic processing of nature. It is an important historical source of popular fantasy, but becomes superfluous with the advancing mastery of nature.

The understanding of myths of the religious and linguist Friedrich Max Müller , who worked in Oxford, was influenced by Darwinism . According to Müller, myths were originally pre-scientific narratives to explain nature; They reported natural phenomena (e.g. the course of the sun) and unique natural events and received their later personified form over the millennia through linguistic distortion of tradition: from the Sanskrit word dyaús (shining sky) are the names of heaven and Father God Dyaus Pita , "Heavenly Father", Zeus Patir (Ζεὺς πατὴρ) , Jupiter , Tyr (Ziu) etc. derived.

According to Friedrich Nietzsche , who was influenced by Müller, the discomfort in modern culture is an expression of a loss of myth. The myth is an " abbreviation of the apparition" ( The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music , 1872). Norbert Bolz states that this rhetoric has a tradition to this day: “The mythless people of modernity lack the power of abbreviation, the horizon limitation that myth provides. The myth is the matrix of the world view - it represents a picture of the world and surrounds the world with pictures ”.

Myth creates knowledge through narration as opposed to scientific explanation . This distinction, used by Aristotle to classify the sciences, was used in the 19th century by Romanticism as a reaction to the advance of the natural sciences to a justification of storytelling over explaining, often combined with a romantic belief in the existence and relevance of folk tales or folk songs . The oral transmission of myths was therefore often seen as evidence of common authorship and ancient agreement of a "people".

The justification of the irrational versus the rational stands in the same historical context. The logos , which is accessible to rational discourse , is often understood as a contrast to myth . In contrast to history , the objects of the myth cannot be verified and are more related to a collective belief in its reality or truth. Scientific historiography can be assigned to the logos today , while myth and the like a. the Doctrine of the Faith , the Literature and Sociology deal.

Since the 19th century, the term myth has often been associated with the idea of repeated confirmation in experience and narration, which opposes a linear concept of time and a progressive approach. Apart from creation myths, according to this view, myth deals with regularly recurring constellations and conflicts. Goethe understood the myth as "human knowledge in a higher sense". With regard to its repetitive structure, he called it "the mirrored truth of an ancient present" (1814). Nietzsche coined the term “eternal return” (1888). Thomas Mann defined the essence of the myth as "timeless always-present" (1928). It is "preconscious", "because myth is the foundation of life: it is the timeless scheme, the pious formula into which life enters by reproducing its features from the unconscious"

20th century

Around 1900, romantic and neo-humanist ideas were combined with the knowledge of a beginning scientific ethnology and psychology . Of Sigmund Freud , the idea went out that myths as projections are interpretable human problems and experiences about human beings. Often in myth, the actions and workings of gods are represented based on human conditions ( anthropomorphic ) (god families, god families). The fact that with this concept of myth properties of Greek mythology are extended to non-European elements earned him the charge of Eurocentrism .

Freud's interest in myth was shared , with differing doctrines, by CG Jung . In contrast to Freud, who understands the myth as a sublimation of mental repression processes, Jung sees in the myth a mirror of a collective unconscious, which is expressed in timeless archetypes that correspond in different cultures .

Even Lucien Lévy-Bruhl noted the rationalist tradition against the idea of fundamentally different types of knowledge to which the myth belong as a collective idea. It is an expression of the bond between groups and their past and at the same time a means of strengthening their solidarity.

The endangerment of orders and values in the period around the world wars, on the one hand, and increasing pluralism, on the other, promoted the belief in a universality of mythical ideas independent of cultures and worldviews. With his book Simple Forms (1930), the literary scholar André Jolles had some influence on myth theory, not only in the run-up to National Socialism . In order to free the myth from the prejudice of the "primitive", he placed it next to the authority of the oracle , which also prophesies. Added to this is the moment of the request: "Next to the judgment that creates general validity, there is the myth that conjures up cohesion." Finally, Jolles perceives the pull of determinism in the myth : "where happening means necessity as freedom, there happening becomes myth" .

Aspects of Myth in Science

The 20th century tried to rehabilitate the myth, not by denying that it is being replaced by modern science, but by showing that it has a function entirely different from science, or that it says nothing about the physical world, but rather must be read symbolically. At least the latter variant ignores a number of important functions of the myth, which are discussed below. Due to the large number of theoretical approaches, it is difficult to draw clear lines of development. Characteristic of myth research towards the end of the 20th century is a "monolateral" interpretation of the functions of the myth, which neglects comparative aspects (according to the Indologist Michael Witzel ).

Myth in Philosophy

The pre-Socratics set myth as a world interpretation in opposition to the knowledge of the logos , whereby the first beginnings of scientific thought, traced back to Thales von Milet , have been interpreted as the beginning of philosophy in general since Aristotle . The myth remains reserved for poetry until the Church Fathers spoke out against the Greek gods, who “are like humans are not even allowed to be”. This “theological absolutism” has an effect up to the Renaissance and Baroque, when the gods had long since found their way back into poetry and painting, but could be philosophically fitted into the Christian worldview by means of allegory .

Only Spinoza's concept of God and the transition to the “supremacy of the subject” through Bacon's concept of science and the empiricism further advanced by Hobbes and Locke allowed the early Enlightenment Giambattista Vico to draft a philosophy of history in his “scienza nuova” in 1725 , in which the poetological-allegorical truth of myths in the early days of man is replaced by an upswing to rational consciousness, which, however, weakens the imagination and thus leads to decline again until a “new science” that Vico saw coming in his time ensures the final ascent.

With the onset of modernity , theology then sees itself incapable of securing the legitimation of the existing order in the face of "mass atheism" in relation to the society in revolutionary upheaval. On the other hand, empirical science, which has become the new guideline with the Enlightenment, cannot serve as a substitute for religion because “its validity claims are fundamentally formulated hypothetically. But hypotheses are not enough to legitimize state power ”In this environment the importance of philosophy increases, and under the new primacy of freedom it is finally Kant's postulates of practical reason, the“ the oldest systematic program of German idealism ”- equally Hegel and Attributed to Schelling - took up in 1797 to formulate the demand for a “New Mythology” as a “Mythology of Reason”: “Philosophy must become mythological in order to make philosophers sensual”. The myth subsequently remains a central theme of German idealism. In the “Process of Mythology” in 1842, Schelling still referred to myths as “products of the substance of consciousness itself” and as fundamental for human consciousness.

Mediated by Schelling's student Johann Jakob Bachofen , the “non-Olympic ground beneath the Apollonian serenity of the Homeric world of gods”, which Schelling addresses in his late work, became, as it were, the heir to the “night side of romanticism”, the antipole of Hellenistic classicism in the most radical Formulated by Nietzsche . Even after the transition from mother right to patriarchy, Bachofen saw the father of the gods Zeus under the rule of the goddess of fate Moira and in this context set the Dionysian against the Apollonian . This contrast becomes a central theme in Nietzsche's 1871 The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music . This clearly shows the latent explosive power of Nietzsche's “de-subjectivizing” myth reception: “Despite fear and pity we are the happily living, not as individuals, but as the one living being, with whose fertility we have merged.” The final step towards “remythization “As the cornerstone of the regained validity of the myth in the 20th century, Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra was probably made in 1885 . The “eternal return of the same” postulated there is not to be understood as a metaphysical statement, but as a provocative offer of interpretation.

Probably the most powerful tradition of contemporary philosophy leads from Nietzsche through Freud and French structuralism to postmodernism , with the structure of myth remaining a central theme.

Ernst Cassirer , on the other hand, is interested in the position of myth in the system of symbolic forms from an epistemological perspective. He characterizes the myth as a separate "form of thought" alongside language, art and science through the following features: The myth as well as the religious ritual make no distinction between different levels of reality ( immanence / transcendence ). He also knows no distinction between “imagined” and “real” perception (dream / waking experience) and no sharp separation between the sphere of life and death. He does not know any category of the “ideal”, because everything (including illness and guilt) has a “thing character”. He regards simultaneity or spatial accompaniment as the “cause” of events (“post hoc ergo propter hoc”). With this description Cassirer approximately follows what Lucien Lévy-Bruhl as prelogical (pré-logique) referred thinking. According to Cassirer, these characteristics of thought can be demonstrated not only in the “real myth”, i.e. the narration of the gods, but also in other types of text such as prayers and songs. On the one hand, for Cassirer, myth, as a phenomenon that creates symbols and the world, is on a par with modern science; at the same time, however, he regards it as a primitive phenomenon.

Under the impression of National Socialism and after his escape to the USA, Cassirer speaks of modern political myths, which he completely relegates to the realm of irrationality. In doing so, he moves far away from Lévy-Bruhl's concept of prelogical thinking (whose work La Mentalité primitive from 1921 was often criticized as racist during World War II, from which Mary Douglas defended him ) and follows Malinowski's functionalist interpretation of myth as a last resort magical control of the uncontrollable. Cassirer does not refer this to the control of physical nature, but to that of society and the state. However, this blurs any distinction between myth and mere ideology .

In contrast to such devaluation, which leads to the assumption that the myth is dispensable, even harmful, for modern people, Hans Blumenberg sees the myth in the tradition of Arnold Gehlen as a form of processing basic existential experiences that overload people. The “narrative” of the myth teaches how to deal with these situations and thus represents a “relief function” (Arnold Gehlen) for people. The myth cannot be translated into clear, non-pictorial language. It is precisely its polyvalence that gives it its wealth and makes its interpretability and applicability (in the sense of comprehension) possible in the most varied of crises. Thus the myth as a world interpretation of imaginary thinking is probably the earliest answer to the human need for orientation and security in the face of the unchangeable “absolutism of reality”. It corresponds to the original structure of human thought: indefinite fear paralyzes, so that the human being strives to transform it into object-related fear that is easier to live with. To do this, he invents names, stories and contexts that make the unfamiliar familiar, explain the inexplicable and name the unnamable. "What has become identifiable by the name is lifted out of its unfamiliarity through the metaphor, and revealed through the telling of stories in what it is about." (Blumenberg) In this way, the non-human is "humanized" and it a relationship to the "big picture" arises. The myth cannot be questioned, it tells instead of substantiating it, it is "the evocation of the permanence of the world in ritual." This refers to the deep roots of the myth in human thinking about the "preservation of the subject through his imagination against the untapped object" Compared to the dream as "pure powerlessness in relation to the dreamed, complete elimination of the subject" and "pure domination of desires."

In 1942, in Der Mythos des Sisyphus, the French writer and philosopher Albert Camus portrayed the ancient figure of Sisyphus as a potentially self-determined and therefore happy person: the persistent senselessness of Sisyphean work shows the freedom of people rather than their devotion to authorities .

In the last chapter of his book Critique of Scientific Reason and in his book The Truth of Myth, Kurt Hübner presents a systematic and substantive (but non-functionalist and non-structuralist) interpretation of myth as an independent conception of reality. He also takes a critical look at the classical and current interpretations of myths and the claims of the natural sciences. In contrast to scientific ontology, he tries to clarify the question of the rationality and truth of myth.

Myth in structuralism and post-structuralism

Since the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss , it has been generally recognized that myths are not “primitive” forms of creating meaning, but rather sophisticated techniques with the help of which an analogy between natural and social order can be established, stabilized and created . They have an epistemic (systematically ordering the knowledge or belief system), social and anthropological function.

In 1949 Lévi-Strauss' Elementary Structures of Relatives , 1962 Das Ende des Totemismus and 1964–1971 the four-volume main work Das Rohe und das Gekochte appeared . Myth is here (as for Edward Tylor , see below) a basic protological structure of human thought in all cultures: in the course of a myth anything can happen, it shows no continuity. Nevertheless, like all thinking, “wild thinking” can be arranged in pairs of opposites, which do not arise from an unlimited imagination, but were obtained through observation and the formation of hypotheses. In this they are similar to the systems of the modern world. In addition, these pairs of opposites (such as the raw and the cooked, exogamy and incest, wild and tamed animals, heaven and earth, overestimating and underestimating consanguinity through incest and parricide, etc.) offer a number of solutions to the contradiction that man himself on the one hand as part of nature and at the same time as a cultural being.

The diachrony , the chronological order of the action, is canceled out in the synchronicity of the pairs of opposites: “One will not hesitate to count Freud after Sophocles as one of our sources of the Oedipus myth. Their versions deserve the same credibility as others, older and seemingly "more authentic". [...] Since a myth consists of the totality of its variants, the structural analysis must look at them all with the same seriousness ”. No element of myth and no group of elements has a meaning in itself, neither literal nor symbolic; they only gain their meaning from the relationship to other elements or groups. The same applies to individual myths as well as to the relationship between myth and ritual. This is borrowed from modern structuralist semiology , which Lévi-Strauss accused of tearing the myths out of their context.

The “wild thinking” inherent in myth (Lévi-Strauss) is just as stringent as modern thinking; it differs from this in that it is adapted to the sphere of concrete perception, while abstract-scientific thinking is set apart from it. The wild thinking is “the translation of an unconscious apprehension of the truth of determinism.” The interpretation is offered in this way “a scheme that has a lasting effect”. Like Tylor, Lévi-Strauss emphasizes the role of myths in controlling cognition; the emotional functions of the myth, such as its ability to process existential fears, take a back seat. The action and thus the narrative interpretation are secondary to the order-creating cognitive structure; the syntax of the myth is, so to speak, more important than its semantics .

The Belgian cultural anthropologist and Lévi Strauss student Marcel Detienne , a co-founder of the École de Paris , sees the compromise between the extremes that appears in many ( above all Greek) myths as a solution to the contradiction of pairs of opposites in myth . Such extremes or compromises on the different levels of the myth are associated with one another. While raw meat and salad form one extreme and spices form the other extreme on the nutritional level, roasted meat and cereals mediate between these extremes. On another level this corresponds to the human being, who stands between the animal kingdom and the spirit beings. These in turn are associated with sun-ripened spices, while raw meat is associated with cold and winter. Salad and raw meat represent abstinence, spices symbolize sexual debauchery and promiscuity . In between there is marriage, which is represented by growing grain and roasting meat. The distribution of the offerings is analogous to this: the spices go to the gods, their smoke rises to heaven.

Even Georges Dumézil treated myths not in a historical perspective, but is interested in the structure comparison. He tries to demonstrate structures under the surface of the myths of the ancient Indo-European peoples, which, unlike Lévy-Strauss, have no order of thought in pairs of opposites, but in three classes that structure the myths, the pantheon and the entire sacred order of life. This so-called "trifunctional ideology" has been forming since at least 1500 BC. The three main classes or castes of the Indo-European peoples: priests (rule), warriors and peasants (growth) and can also be found in the heaven of gods. Their discovery became important for the development of comparative religious studies. According to Dumézil, the gods have on the one hand a magical and on the other hand a judging function. The identity of two gods results from their analogous function in the respective pantheon. However, the trisection fits z. B. not to Nordic mythology, which knows no priests but slaves. Witzel considers the myth systems examined by Dumézil to be an attempt to exclude the lower classes and castes from the mythical privilege of divine descent in the process of the formation of early state structures . While the classes of Arya traced their ancestry to the sun, is the lower class in Sanskrit as अमानुष (Amanusa) , referred not human or un-human.

Other structural classification approaches come from Mislav Ježic and Franciscus Bernardus Jacobus Kuiper . The predominant conceptual model in myth research is that of the family tree-like classification of the Indo-European languages, which should allow the reconstruction of a hypothetical original language. Bruce Lincoln reverses the model and analyzes the ramifications of the original Indo-European myths (e.g. the narrative of the pair of brothers * Manu - a priest who structurally corresponds to Odin or Romulus - and * Yemo - Ymir or Remus , a king who is the stealing of cattle plays a central role). Lincoln interprets these myth adaptations in the tradition of Antonio Gramsci as authoritative (empowering) narratives through which class boundaries are drawn as in Dumézil's system.

Michael Witzel examines the myths of many peoples from a linguistic point of view and from a comparative and historical perspective. He extends the structural-genetic model of Indo-European studies by comparing structures with myths from all other linguistic regions and includes historical aspects in the comparative analysis. In doing so, he criticizes Robert Bellah's understanding of myths , who, in his distinction between the stages of religious development, postulates a primitive pre-lithic stage in which physical phenomena are directly represented by mythical figures that are unrelated and individually venerated, and a second archaic stage with ideas a systematic divine order, which is expressed in myth systems . According to Bellah, this is in turn followed by the stage of historical religions. But just because there are no archaeological references to complex late Paleolithic myths or because the existence of images of shamanistic activities on early cave paintings is disputed, according to Witzel, their existence cannot be ruled out. From the fact that simple hunter cultures hardly leave any archaeological traces, the conclusion should not be drawn that in the period from 50,000 to 20,000 BC. BC did not carry out an evolution of complex myths. Complex syntactically structured language has existed for 40,000 to 50,000 years, so that oral traditions have been passed on verbally since that time. He dates the origin of structured myths to the time of the late Paleolithic rock painting and, especially in structured form (as a story-line ), grants them great stability in their tradition.

The permanent and current validity of the structure of the myth is the subject of semiology , for example in Roland Barthe's Myths of Everyday Life , where he is extremely critical of the “legibility” of the myth: “The consumer of the myth understands the meaning as a system of facts. The myth is read as a system of facts while it is only a semiological system. "

The position of postmodernism on myth as a model for explaining the world is critical , as can already be seen in the title of Anti-Oedipus by Deleuze / Guattari . In the preface to the second volume, Mille Plateaux , it says about Nietzsche: "Nietzsche's aphorisms only break up the linear unity of knowledge in order at the same time to refer to the cyclical unity of eternal recurrence, which is present in thinking as something not known."

For most post-structuralists and linguists (as was the case for Albert Camus ), myths are autonomous texts that are separate from any ritual practice and speculating about their origin and purpose is prohibited.

Myth in Psychology

Even in antiquity, efforts were made to interpret the events depicted in myths as symbols of the human psyche. For example, Lucretius put forward such an interpretation in his didactic poem de rerum natura . In it he tried to explain the famous torments of Tantalus , Tityos and Sisyphus from his naturalistic-rational worldview. Accordingly, the fear that Tantalos has of the stone floating above his head stands for the constant fear of the punishing gods. Tityos feels no pain because eagles are tearing the constantly growing liver out of his body, but because he is consumed with longing for love. Sisyphus is the symbol of the restlessly striving human being, who is never satisfied with what has been achieved and never comes to rest.

For the peoples psychology and apperception theory of the second half of the 19th century and the turn of the century, the myth was the way of looking at and thinking of the "primitive" person, for whom every view became a symbol ( Wilhelm Wundt , Heymann Steinthal , Eduard Meyer ); he has nothing to do with religion. For Wilhelm Dilthey , too , myth was not a religion, but a stage of intellectual development.

From Adolf Bastian , the founding director of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, the idea was the "elementary idea" that is, of ancient myths that have occurred in widely separated parts of the world, it does not seem that by diffusion were common. He explained this phenomenon through the homogeneity of the human psyche and thus prepared the archetype concept of CG Jung, although at the same time he followed Tylor's theories.

As early as 1896 Sigmund Freud spoke of “endopsychic myths” on which he built a “metapsychology” as “orientation for the construct of inner dramaturgy” (where he mentioned Oedipus for the first time), but rejected this thesis again because it ultimately went backwards would have led to the “innate ideas” of Plato. In the " Interpretation of Dreams " from 1899 he distinguished between the manifest (literal) and the latent (symbolic) level of meaning of (dream) myths. On the manifest level, for example, Oedipus fails in the attempt to escape the fate predicted for him. On the latent level, he is successful in satisfying his secret desires. On an even deeper level, the (male neurotic) reader or the dreaming is captivated by the myth and becomes its originator again by finding satisfaction for his repressed desires by acting them out symbolically. Myths are just dreams made public. In his late work in 1937 Freud defined the myth as the “latency of prehistoric human experience”.

Otto Rank followed up on Freud's early work , who also saw dreams as the symbolic satisfaction of repressed desires, but also a differentiated plot structure of the hero myth - especially in the first half of life until the establishment of one's own self - in the form of an "average legend" based on 30 myths worked out. Birth (as the first experience of fear of death, which even comes to the fore in Rank's later work) and survival were considered heroic deeds for him. On the literal level Oedipus is an innocent victim, on the symbolic level he is a hero because he dares to kill his father.

Carl Gustav Jung described myths as the expression of archetypes , that is, deeply anchored in the unconscious, but not individual, but rather collectively inherited human ideas and actions that can appear anywhere - in dreams, in visions, in fairy tales. In contrast to the unconscious archetypes, however, myths according to Jung are conscious (“secondary”) elaborations of these archetypes. Especially the myths of the gods - the gods symbolize the archetypes of the parents - reflect the actions and activities of people in an easily recognizable manner; Even their representation, therefore called anthropomorphic , is mostly analogous to human circumstances or experiences that are only projected into the world of gods (e.g. families of gods, gender sequences, marriage quarrels, deceit and cunning of the gods in Greek mythology ). Archetypes and myths can be lost or suppressed over a long period of time. B. the myth of the mother goddess in Christianity, which reappears in the form of the veneration of Mary (so-called atavism ).

For CG Jung, the myth always harbored dangers: The strong identification with archetypes such as that of the puer aeternus (eternal youth) with the archetype of the great mother (in contrast to Freud and Rank not with the concrete mother or a substitute figure) in the Adulthood to life as an eternal mental infant. The archetype as such is a reality to be accepted, but the concrete puer aeternus gives up its ego in favor of the unconscious; he strives for a return to the prenatal state of mystical unity.

The antagonism between myth and enlightenment was ultimately interpreted by the representatives of the archetype concept in favor of the myth: The myth is viewed as a ritual repetition of primeval events , as a narrative processing of human primeval fears and hopes. In this role he has an irreparable lead over conceptual systems . According to this view, myths, as pictorial interpretations of the world and life interpretations in narrative form, can contain general truths and prove to be indestructible.

This is what the ideas of the classical philologist and religious scholar Karl Kerényi , who dealt with Greek mythology, stand for . Influenced by CG Jung, Kerényi spoke of psychology as individual mythology and of mythology as collective psychology. According to Kerényi, the etymological definition of “mythologia” as the telling (“legein”) of stories (“mythoi”) only refers to a second glance at a “basic text” that the myth constantly varies. "In mythology, storytelling is already justified". The myth is timeless, “since time immemorial it has been both undivided; Present and past. This paradox of the simultaneous and the past has always been there in myth ”.

The linguist and mythologist Joseph Campbell , a student of the Indologist Heinrich Zimmer , is considered to be one of the founders of comparative myth research. In his book " The Heros in a Thousand Shapes " (1949), he examined the myths of the second phase of life, unlike Rank, who looked at childhood and adolescence: the hero's journey as the departure into a new (supernatural or gods) world and existence of Adventures. For him, myths express normal developmental aspects of personality. His myth readers live out the adventures only in the spirit; the myths merge with the everyday world to which the heroes and heroines always return. Campbell emphasized the local forms of adaptation and limitations of universal elementary myths, which had occurred since the time of the early advanced civilizations for reasons of legitimation of power and social integration. This questioning of myths reached its climax with the Second World War. As a specific form of adaptation of the myth to American society, he identified the monomyth of the lone rider who fights against evil. Film and television are the places where myths are developed today.

The American ethnologist Alan Dundes also regards the myth from a depth psychological point of view as a system of wishes. Dundes worked out the many unconscious wishes and utopias that are concentrated in myths and fairy tales, but left it open as to what role the myth plays in the social channeling of these wishes. Standing in the tradition of Mircea Eliades, he gave the myth, in contrast to fairy tales (folktales) , a sacred meaning. In them the supernatural manifest itself.

Donald Winnicott , a representative of the British school of object relationship theory , saw myth as an intermediate area of experience that relieves people from the strenuous task of permanently relating internal and external reality to one another. The myth is the continuation of children's play in the transition to the adult world; like art and religion, it creates its own world of meaning and security in the outer world.

Today most modern exponents of depth psychology see the role of myth as positive for normal ego development. It not only creates symbolic satisfaction for the repressors and neurotics and does not support flight from the world like the dream, but teaches as a collectively shared experience the conscious renunciation, the sublimation and the confrontation with reality. In this, the myth is fundamentally different from the dream - according to the psychoanalyst Jacob Arlow - but also from the fairy tale, which, in contrast to the heroes of the myth, is a gentler, more everyday socialization instance - according to Bruno Bettelheim .

Recently, a scientific dialogue between neurobiology , anthropology and religious psychology deals with myths, e.g. B. with the question of why people repeatedly operate with teleological models that end at an intentional authority.

Myth and ritual in Anglo-Saxon social and cultural anthropology

The British School of Social Anthropology , which was partly based on preparatory work by classical philologists and Protestant Bible Students, examined above all the relationship between myth and ritual, whereby in its early phase it was hardly able to carry out its own field research, but had to rely on reports from explorers, etc. It is characterized by its broad, interdisciplinary approach, which included ethnological, sociological, ancient and religious studies, orientalistic, psychological, evolutionary and philological aspects. These studies were continued by the American school of cultural anthropology founded by Franz Boas , where Boas, in contrast to evolutionist approaches and global dissemination studies of myths, which were fashionable in his time, called attention to the specific and cultural realities of a region, but the Fact of the further spread of myths as narratives well recognized.

For Edward Burnett Tylor , myth (which he ascribed to the field of religion) was a kind of prelogical proto-science that is in the same relationship to ritual as science is to technology: According to Tyler, rituals are developed and based on myths serve (the attempt) to dominate or control nature (so-called ritual-from-myth approach ); they are, so to speak, applied myths. Due to the regularity of the rituals, the myth can be understood as a law for the corresponding action. The myths are no longer needed as soon as modern religions or ideologies are based on developed ethics and metaphysics .

For the Scottish Presbyterian , anti-Catholic (and thus anti-ritual) Arabist William Robertson Smith , on the other hand, myths were only explanations for religious rituals, the cause of which is no longer understood. So the ancient peoples accompanied the cycle of vegetation through rituals. Of the ancient oriental vegetation cults, only the Adonis myth remained alive with the Greeks (so-called myth-from-ritual approach ). For Robertson Smith, the early religions were essentially collections of rituals, not of ideas or narrations that later emerged from them. However, the question of the cause of the ritual remains unanswered.

Similarly, the literary theorist Stanley Edgar Hyman (1919–1970) postulated that the (prelogical) ritual was older than the myth, which subsequently became a (logical) “etiological narrative” to explain natural phenomena.

Robertson Smith influenced the extensive work of James George Frazer The Golden Bough (1890; expanded 1906–1915) about the god of the plant world who died in the course of the year by cutting and pounding the grain, descending into the underworld and rising again in spring, as he did in the originally described in the Near Eastern Adonis myth. For Frazer, the gods were only symbols of natural processes. The "natural law man" is quite capable of logical thinking, but he uses magical rituals when he reaches the limits of his causal understanding of nature, and when these rituals fail - for example in the event of bad harvests - myth, i.e. belief, helps him invisible powers to come to terms with the limits of his power. So the myth describes natural processes; it precedes the ritual that becomes a purely agricultural process. Frazer further distinguished between myth and magic : magic is also based on belief, but like science, it is geared towards verifiability. The same cause will always produce the same effect.

The classical philologist Jane Ellen Harrison, on the other hand, considers the myth to be only a verbal form of ritual, a kind of speech act that, however, has magical qualities itself. From Frazer it takes over the willingness to classify the religion of the Greeks and the Jews as rather primitive. Gods are projections of the euphoria triggered by the dramatic power of the rituals . According to both Frazer and Harrison, myths serve to protect rituals from being forgotten and to introduce new members into the community. They can become independent and detach themselves from the ritual; or the ritual becomes independent and is carried out around itself, which for Harrison is the origin of every kind of art .

Even Samuel Henry Hooke and recently Gregory Nagy speak a word performative magical significance to the myth.

The role of myths and rituals as instances of socialization, but also as a symbol of aggression and killing rites, is emphasized by the German classical philologist Walter Burkert , who, like the explorer of the Navajo , Clyde Kluckhohn , considers myths and rituals to have arisen independently of one another, but examines how their effects develop mutually reinforced. The ritual turns a simple story into a social norm; the myth lends a divine legitimation to human activity.

For Bronisław Malinowski it was not the ritual but the social legitimation function of the myth that was in the foreground. He considered myths to be a subsequent or accompanying legitimation of rituals; But there are many everyday activities about which myths are also told, or heroic myths that are supposed to encourage emulation. Myth and ritual are therefore not necessarily linked. Myths and rituals did not primarily serve to explain natural or physical phenomena, but rather to cope with social demands. The myth is supposed to justify uncomfortable moral rules, rituals and customs. Its function is not to explain the rituals, but to legitimize them by locating their origins in the distant past. In this way the myth makes it easier for people to recognize it. Myths are part of the diverse functional (economic, social or religious), pragmatic and performative elements of a culture, i.e. not just pure imagination, reflection or explanation, but components of reality that determines action. They are therefore only to be understood as part of the actions that fulfill certain tasks in certain communities, and only through participatory observation and dialogue with the mythmakers .

Citing Malinowski, Mircea Eliade argued that many rituals are only carried out because one can rely on an origin myth or imitate a mythical figure who is said to have founded the ritual. According to Eliade, myths not only legitimize rituals, but also explain the origin of the most varied of phenomena (so-called “etiological myths” ). The myth works as a kind of time machine; he brings people close to the old gods or heroes. In contrast, Witzel regards the relationship between myth and ritual as an undecidable chicken-and-egg discussion (Witzel 2011, p. 372).

Robin Horton (1932-2019) was often referred to as a Neo-Tylorian ; but for him personalizing (mythical) explanatory models of the world are not connected with “primitive” or religious thinking per se, but they arise in an environment in which things are not predictable and less familiar than people, i.e. in non-industrial cultures. This social context determines the form of thinking: In African religions, the final decisions are basically ascribed to human-like beings. For Karl Popper , who followed Horton's thinking and radicalized his theses, there was ultimately no fundamental difference between the structure of myth and that of Western science; The latter, however, is embedded in a culture of discussion and can be checked, but the myth is not.

Like many British ethnologists, he thus takes a contrary position to that of the French ethnologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl , who considers mythical thinking to be prelogical. The Polish-American cultural anthropologist Paul Radin , a student of Franz Boas and researcher of the cult of the Winnebago and their epic accounts of the deeds of their cultural heroes , is also a sharp critic of Lévy-Bruhl. He assumes that people in “primitive” societies can also think non-mythically, even philosophically. The difference between the thinking of the average person with a tendency towards myth as a mechanical explanation of repetitive processes (in the sense of Nietzsche's return of the same thing) and the thinking of the exceptional personality is pronounced in a similar way in all societies.

Today ethnology sees the definition of the role of myth in the structural-functionalist approach of Malinowski and other authors as too normative and static. In contrast, she emphasizes the permanent evolution of myths in the process of social change. This brings the active role of the mythmaker to the fore. In this sense, Joseph Campbell previously distinguished left- and right-handed myths. The latter are norm-compliant and support the social status quo. Left-handed myths, on the other hand, testified to social innovation through successful rule breaking (e.g. the myth of Prometheus ),

Myth in sociology, political science and history

The social and historical sciences have not yet been able to agree on whether to use the term “myth” in the everyday sense or as a theoretically defined term for people, collective movements and events that have become the subject of a public cult. While processes of (modern) myth formation are on the one hand the subject of sociological and historical investigations, historical myths were on the other hand sources that could provide information about the social structure of earlier societies (such as the analyzes of Georges Dumézil). Historians have also been reflecting on the concept of myth for several years as part of the cultural-scientific turnaround in the subject and are examining the formation of traditions, collective memory and mentalities.

The basis of sociological research into myths was created by Émile Durkheim with his investigations into totemism in Australia. He did not start from an evolutionist paradigm, but realized that the natives of Australia had created complex religious systems that fulfilled functions similar to those of the world's religions. According to Durkheim, the core element of the religious is the distinction between two absolutely separate spheres: the sacred and the profane. In the secularized modernity, society replaces religion in the collective ideas of people: They believe in the social order and set up institutions and rites to stabilize it. Similarly, Robert Bellah defined civil religion as the religious part of the civil culture of a democracy through which a protective canopy of beliefs and myths is erected over it that legitimize the social rules.

For the French socialist Georges Sorel , for whom the truth of the myth was indifferent, myths, on the other hand, are guiding ideologies, images of great battles that have to be fought in order to put society on a new moral basis; they have a mobilization function (like the myth of the general strike of the syndicalists , the Marxist myth of the final crisis of the capitalist system or the Catholic struggle between Satan and the Church). For Benedict Anderson , all large communities that go beyond village face-to-face communication are imagined communities; they need powerful community ideas. This is true not only of modern societies, which Anderson studies, but also of earlier founding and historical myths such as B. for the Deuteronomistic History , which legitimizes the construction of a Jewish central state and shows the reasons for its collapse from a theological point of view.

The legal scholar Otto Depenheuer reminded that many heads of state and legal theories are backed by myths, the Leviathan of Thomas Hobbes . For Depenheuer, the religious as well as the political myth (as for Nietzsche) is a “contracted worldview” that responds to “fear of contingency, confusion and disorientation” and coherence as well as a feeling of “being lifted” and of identity through fading out structures and reduction of complexity. The rationalist state, law and the constitution are not free from mythological thought patterns, narratives and the rituals that correspond to them. For Samuel Salzborn , the ultimate goal of political myths is the reconciliation of opposites, the resolution of ambivalences , i.e. a kind of symbolic conflict management. In it he follows Lévi-Strauss.

The everyday use of the term myth, which is opposed to the term “truth”, ignores from a sociological point of view that conceptual constructs and collective ideas are just as right part of reality and legitimate research objects as the “hard” historical and social facts.

Matthias Waechter defines myth from a sociological point of view today as follows: “Myth refers to history that was shared and shaped by outstanding individuals [...] (This) is removed from its immediate, time-bound context in the process of mythologizing it and raised to a timeless level; their protagonists are given transcendental attributes. ”The myth fulfills a key role in the acquisition, legitimation and stabilization of political authority; but not everyone is allowed to interpret it. One example of this is the market economy myth of the " invisible hand " that is widespread in the economy . The 20th century as an age of catastrophe experiences brought with it an inflation of the production of myths, because in times of crisis the urge for political mobilization and the need for consolation and meaning are particularly great.

Personal myths are not limited to authoritarian, dictatorial systems: even in modern republics, leaders were charismatized, such as B. Ataturk . For Thorstein Veblen , the infantile excess of desire is the cause of hero worship and many myths; this reflects the early days of a predominantly predatory economic system; but the myths of capitalism and their heroes are, according to Veblen, make-believe .

In pluralistic societies, extremely opposing currents are often mythicized with their respective heroes. B. in the USA the vanished southern culture (Johnny Reb) and the myth of the slave liberators (Billy Yank) . Even socially ostracized subcultures with their heroes and their opponents become the subject of myths (such as Al Capone or Eliot Ness and the group of the incorruptible ). The USA in particular has become a haven for the inexhaustible production of heroic and social myths - sometimes in extreme metaphorical abbreviation - from George Washington , "who never lied", to the melting pot and rags-to-riches , who became a millionaire. While technology itself has become a myth today, on the other hand, information technologies have fundamentally changed the way modern myths come about and how they work. These arise today from a communicative process in which producers and recipients interact. This creates a demand for ever new myths and a market for commercially produced art myths, in the course of globalization above all for transnational, culture-independent myths (e.g. Star Wars ).

Myth and Religious Studies

Rudolf Bultmann examines Christianity for the explanatory models contained in the New Testament , which when interpreted literally appear primitive, and for forces at work in the world (e.g. " Satan "). He encourages you to read this symbolically models and distinguishes between Demythologisierung and demystification . While the latter consists in the attempt to find a scientifically verifiable core for the myths and to discard the rest of the myth, the result of the demythologization is the symbolic core of meaning of the myth that has to be extracted. A myth understood in this way is not about the world itself, but about the human experience of the world. The myth expresses "how man understands himself in his world"; it wants to be interpreted anthropologically, not cosmologically. According to this interpretation, the New Testament is about the alienation of those who have not yet found God and the feeling of oneness with the world of those who have found him. In order to be able to accept myths, one must continue to believe in God - so the criticism of Segal.

Similarly, demythologisiert Hans Jonas , the Gnosis and reduces it to the fact of the alienation of the people. In order to defend Gnostic mythology, however, he has to "demythize" it by sacrificing all elements that contradict modern science. While for many myth theorists - above all Tylor - the effect of the myth was that it was taken literally, the modern religious studies on the contrary assume that its effect (on modern Christians) only arises through symbolic reading or allegorical interpretation. It is more than doubtful that this reading of the myths proposed by religious studies was also that of the earlier peoples.

Even for Mircea Eliade , myths cannot be read symbolically. For him, however, unlike the Anglo-Saxon school of social anthropology and ethnology, it is not about explanations of the eternal recurrence of phenomena, but about origin and founding myths that express a coherent system of statements about ultimate realities - i.e. a metaphysical system. The myth is the "ritual recitation of the cosmogonic myth, the reactualization of the primordial event", through which man is projected back to the beginning of the world and is united with the gods. This union would undo the post-paradise separation. The “benefit” of the myth consists in the encounter with the divine. Science cannot provide this, and therefore modern man needs myth, even if he does not want to identify with gods but with profane heroes. Ultimately, there was no secularization at all: Even the cinema today offers modern people the opportunity to “step out of time”. However, the question remains as to whether the person really feels as though he has been transported back in time or just imagines the past - ultimately an open psychological question.

Witzel postulates that the idea of the divine origin of heaven, earth and man did not spread through diffusion. Ultimately, all high religions can be traced back to this idea, which belongs to what he called the late Paleolithic Laurasian myth complex that branched out locally with the spread of modern man. This contains the elements of creation, death and rebirth (of animals as well as humans), so it represents a metaphor of the human life cycle. In the Neolithic this thought was further developed to the idea of descent from the sun; Animal sacrifices and shamanistic rituals have been replaced by the worship of plants and the idea of the rebirth of the earth in spring - later by anthropomorphic vegetation gods such as Osiris and Adonis. At the same time, the elites excluded the lower classes or castes from the privilege of divine descent in the time of the early state formation, as in Egypt, India, China, Japan and among the Inca and Aztecs, although there were contradictions and internal conflicts in the construction of the myths came. Under the influence of monotheistic Zoroastrianism with its dualism of good and evil, the idea of an "automatic" rebirth was lost. The Paleolithic element of animal sacrifice has been preserved to this day partly in symbolic form (“ Lamb of God ”). The Islam constitutes the most modern and most abstract version of the great religions, but still the Feast of Sacrifice Socialize on to the stone-age tradition.

Myth and Literary Studies

In connection with the ritual, the myth can be understood as a magical or religious (practical) text. According to many scholars, it only becomes literature, i.e. an autonomous text, when it is separated from the ritual. Significantly, the ancient “pagan” myths have often survived without the religious ideas and rituals associated with them, which is not the case for the Old Testament myths: today, knowledge of these is largely limited to the group of followers of Christian religions. Most of the Nordic myths , which have only survived in literary form (as skaldic poems ) and were partly influenced by Christianity at the time of recording , present today's reader with great problems of understanding. However, this is less due to the (now almost complete) ignorance of the magical, shamanistic or religious ideas and rituals originally associated with these myths , but rather to the mannered, technically extremely demanding and puzzled poetic form of poetry ( Kenningar ) interspersed with Lecture before kings and nobles was intended. A separation of the original myths from the literary invention is hardly possible.

- The origin of tragedy and heroic epic in ritual

British anthropologists and classical scholars have tried many times to derive the origin of mythical narratives from meaningless or dead rituals. FitzRoy Somerset (1885–1964), the fourth Baron Raglan, an amateur anthropologist, studied the origins of heroic myths in particular. In his opinion, these have their origin not in history, but in rituals that are no longer practiced. What remains are idealized heroes with an ideal biography. From a multitude of heroic stories, Lord Raglan filters out 22 epics or myths from 22 life phases or character traits. The pattern of heroic life depicts the king as an exemplary mythical savior, who is to serve as a model for the real leaders and who sacrifices himself for his people or is driven from the throne. In this pattern e.g. B. Oedipus or King Saul . Although Lord Raglan also saw Jesus in this series, he “forgot” about him in his book in order to avoid conflict with the publisher.

René Girard explicitly ties in with Frazer's scenario of the mythical-ritual and implicitly with Lord Raglan, without directly quoting him. For him, all myths are reports of the use of violence, which always show the same polarization: all-against-all, all-against-one and brother-against-brother. He lets the people banish or kill his hero in an outbreak of violence because he is the author of their misery (e.g. Oedipus the author of the plague). In a later phase, however, the criminal can become a benefactor or hero again.

For Frazer, however, the process of killing the plant god (or a king who is no longer fertile) is a fertility ritual; this serves a purely agricultural purpose and is not accompanied by outbreaks of hatred. Accordingly, the king or god must be replaced or rejuvenated. The drama theorist Francis Fergusson sees this as a root of the drama, which is essentially about suffering and redemption, even if the focus is not on the sacrifice of the king by the people, but on his self-sacrifice. For him, the king of Shakespeare's drama is symbolic of God.

While Walter Burkert emphasizes the similarities between myths, sagas and fairy tales as traditional, supra-individual narrative forms (with myths using real proper names), André Jolles does not distinguish myth from other simple narrative forms such as legends and fairy tales by their underlying narrative patterns, but by different attitudes to the world, which are embodied by them: The legend builds the world as a family and interprets it "according to the concept of the tribe, the family tree, the blood relationship". The fairy tale is determined by an ethic that “answers the question: 'How must it be in the world?'”; the myth, on the other hand, is characterized by inquiring questions. In this respect one could speak of an anthropological rather than literary justification of the myth.

The Canadian literary theorist Northrop Frye sees the root of other literary genres as well, especially those that deal with the life cycle of a hero (birth and awakening, triumph, isolation and overpowering), the Frye with the cycle of the four seasons, the daily cycle the sun and the cycle of dream and awakening. For example, Frye associates comedy with spring, tragedy with autumn.

Gilbert Murray , of Nietzsche's theory of the Dionysian developed, sees the origin of the tragedy in myth and ritual of suffering, death and resurrection of the annual spirit or daemon, a sacred Dionysian dance, which, by the elements of competition, defeat Epiphany is marked to the later the complaint and the report of the messenger are added. Many scientists have joined this position to this day.

For Kenneth Burke , myths are metaphysics turned into narratives. They symbolically express something that people of earlier cultures could not express literally. For him, the six days of creation stand for an attempt to divide the world into six categories.

The postmodern reduction of the myth to a mere narrative and its separation from the ritual come from the perspective of these approaches a trivialization of myth same.

Rosario Assunto sees that the process of separating literature from myth and ritual has been reversed since Romanticism and since Dostoevsky . Since then, with the exception of realism and naturalism , the purely aesthetic and aesthetic has been transformed back into myth. The more philosophy in the 20th century withdrew to logic and the philosophy of language and created a world without myths, the more literature took over the task of philosophy and filled this void; she turns away from pure vision and becomes a bearer of meaning again. Scenes become symbols, literature descends to the unformed unconscious and brings it to consciousness. Cesare Pavese judges the role of literature in a similar way : It gives the myth a form without becoming addicted to the unconscious.

- Myths in Literature

Francis Fergusson distinguishes between literature that is constructed on the model of myths (e.g. The Metamorphosis of Kafka, works that themselves achieve mythical quality (e.g.) Moby-Dick by Herman Melville or the plays by Federigo García Lorca ) and works that address myths from the past.

The Greco-Roman myths were always of particular importance to European culture. Since Homer's Iliad and Odyssey and Hesiod's Theogony , they have become the subject of poetry and the subject of artistic elaboration. Callimachus of Cyrene collected around 270 BC. Chr. Founding myths and put them in his work Aitia together. In Roman times, Ovid collected transformation myths in his Metamorphoses . While the ancient myths were closely connected with natural phenomena and turned towards this world, they were understood by the Church Fathers as moral doctrines from a Christian-critical perspective. In later Christian times new, worldly and nature hostile myths emerged, in which the ethical dualism and eternal struggle between good and evil, God and Satan were reflected.

Petrarch , Dante , Chaucer , Shakespeare , Milton and many others made use of ancient myths in their works, which provided them with numerous literary motifs. The Aristotelian view that the tragedy should be about "better people" led to the so-called class clause , which reserved the myth of an aristocratic world of gods and nobles and excluded the bourgeoisie since the 17th century . As a weakening of this once explosive delimitation explains the view that the myth deals with gods and the legend with humans (although Oedipus, for example, is a prince and not a god).

Since the end of the 18th century, classical mythology, as a sign of overcoming the aristocratic French classics (see tragedy ), has been replaced by medieval and exotic materials, which in turn gained mythical significance. The Weimar Classic , on the other hand, tried to make the antique fabrics bourgeois and in this way to keep them alive. Ancient myths began to reappear in the late 19th century; numerous works by Jean Giraudoux , Albert Camus , Jean Anouilh , Jean-Paul Sartre or Eugene O'Neill often refer to it in the title.

Examples of myths that have arisen in modern times, which can be found in numerous variants, are the fist cloth or the motif of the womanizer Don Juan . The Pygmalion fabric or Romeo and Juliet , on the other hand, can be traced back to ancient models . Modern literary myths such as Star Wars also follow the typical life cycle of ancient heroes and use elements of classical myths such as the labyrinth , the wise advisor or the “guardian of the threshold”.

Types and functions of myths

Regarded as a narrative that provides an “orderly description” of the world, various types or functions of myths can be distinguished:

-

Creation myths :

- Cosmogonic and cosmological myths tell of the origins or creation of the world and explain its structure and course (see e.g. African cosmogony , Indo-European creation myth). In many such myths, the primordial sea, primeval chaos, primeval or a primeval animal play a role (e.g. the turtle that carries the cosmos).

- Anthropogonies tell of the origin of humans, such as B. the myth of Ask and Embla or that of the creation of man from the tears of the sun god Re .

- Theogonies tell of the origin and fate of the gods (see Hesiod's theogony and the Orphic theogony ).

- Founding myths lead the building of a sanctuary or a city or the ethnogenesis of a people or tribe ("ethnogony") back to gods, forefathers or heroes.

- Myths of origin (also genealogical myths, myths of origin or origines gentium ) are intended to increase the importance of ruling dynasties or entire peoples through fictitious chains of descent.

- Genealogical or charter myths (a term coined by Malinowski) and sociogonies legitimize certain lineages and property claims; they are often associated with myths of origin (e.g. Landnámabók and Íslendingabók with the thesis of the alleged descent of the Nordic kings from the Trojans ).

- Historical myths often serve to derive a national identity (e.g. Deuteronomy , which explains the origin of the Jewish state, or the Tell myth ). They are precursors to modern political myths that follow them almost seamlessly. So who served Bogomil myth in both Austria-Hungary after 1900 and in the modern Yugoslavia in 1970 to direct ethnic continuity from Bogomil nobility of the Middle Ages to modern Bosnian Muslim to derive elite, without recourse to the identity criterion of the Muslim faith to have to.

- Hero myths are about people with superhuman strength or demigods who strive for great goals that exceed normal human capabilities. Their creativity and creativity never dry up (like that of Odysseus ); with their actions they become role models for others. Often they are deified because of their deeds ( Heracles , Indra ). Modern hero myths often serve as motivators for authoritarian or totalitarian regimes.

- Etiological myths explain particular phenomena in the world that require explanation.

- Soteriological myths tell of the coming of a Savior to bring salvation to the world.

- Myths that tell of cultural heroes like Prometheus , Maui or Huangdi describe the invention or transmission of important cultural techniques that are often stolen from the gods. They are related to rogue or trickster myths that tell of creative people or demigods who are capable of amazing acts of creation. In many cases the culture bringers are also gods of agriculture and gods of the dead in one person, which refers to the constant exchange between the two areas. On the threshold of the modern age, Francis Bacon drafts Chapter XI of his book The Wisdom of the Ancients , which is entitled Orpheus, or Philosophy. Explained of Natural and Moral Philosophy carries a new Orpheus myth in which the hero stands as a metaphor for a philosophy that - overwhelmed by its traditional tasks - is not limited to searching for divine harmony in the world, but to itself turns to human works, teaches people virtue and guides them to build houses and cultivate their fields, i.e. to actively change the world.

- Eschatological myths tell of the "last things" (eschata) that will happen at the end of time or after death.

- Antimyths or myths of destruction. While the creation myths are supposed to explain the existence of man in the world, the antimythos tries to ban or rationally explain everything that oppresses or questions his existence.

Large parts of the Bible, the traditional counter-world to the ancient pagan "myth", can be viewed as a collection of myths. This thesis by David Friedrich Strauss was a major provocation in 1836. In this sense, the Genesis of the Pentateuch contains mythical tales such as the creation of the world in seven days and the Garden of Eden . However, certain aspects typical of other founding myths are missing. Due to the monotheistic perspective, there is no question of conflicts within a polytheistic pantheon ; the conflicts between God and humanity arise solely from their sinful character. While the Flood in the Babylonian model of the biblical story (in the Atraḫasis epic ), for example , appears to be motivated by a conflict between different deities and only accidentally triggered by the annoying noise of people, the Bible has to find other culprits for this: The general badness of people serves the motivation for the flood, which, however, also appears to be insufficient justification for the severe punishment.