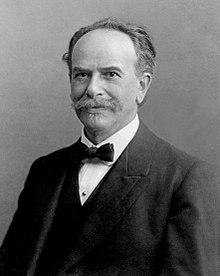

Franz Boas

Franz Boas (born July 9, 1858 in Minden , † December 21, 1942 in New York ) was a German-born American ethnologist , linguist , physicist and geographer .

family

Franz Boas came from an in since 1670 Westfalen -based Jewish family. The family name is of Hebrew origin (see Boas ). Franz Boas' grandfather, the merchant Feibes Boas, had been a citizen of the city of Minden since 1821 .

Boas' parents were Meier Boas (born November 10, 1823 in Minden; † February 21, 1899 in Berlin) and Sophie Boas, b. Meyer (born July 12, 1828 in Minden; † 1916). The marriage on August 28, 1850 had five children. Franz Boas was the third child.

A maternal uncle by marriage was the pediatrician Abraham Jacobi . He was married to Fanny Meyer (1833-1851), a younger sister of Sophie Boas, in his first marriage.

On March 10, 1887, Franz Boas and Maria Krackowizer (born August 3, 1861 in Brooklyn, † December 16, 1929 in Grantwood, New Jersey ) married in New York. She was the daughter of the surgeon Ernst Krackowizer (1821–1875), who fled Vienna to the USA after the revolution of 1848 . Franz and Maria Boas had six children; as the youngest child the dance therapist Franziska Boas .

Life

Childhood and school days

Franz Boas' childhood was largely shaped by his mother, who also encouraged his interest in science. After attending kindergarten, he received private tuition and was then accepted into the fourth grade of the community school for children of wealthy parents. When he was almost 9 years old, he switched to high school in Minden , where his success at school was impaired by health problems. On February 12, 1877 he passed the Abitur.

Education

Franz Boas began studying mathematics, physics and geography at the University of Heidelberg in April 1877 . After one semester, he moved to the University of Bonn . His cousin Willi Meyer, who was the chief surgeon at the German Hospital in New York from 1887 to 1923, also studied here. In the winter semester of 1877/78 he joined the Alemannia Bonn fraternity like his cousin .

In Bonn Boas met the geographer Theobald Fischer, whom he followed in 1879 to the University of Kiel . 1881 Franz Boas was in Marine Physics of Gustav Karsten with the thesis contributions to the knowledge of the color of the water doctorate . This was about the question of why water appears blue.

After receiving his doctorate, Boas spent a vacation in the Harz Mountains at the invitation of his maternal uncle Abraham Jacobi , where he met his future wife. In October 1881 he began his military service as a year old in the infantry regiment "Prince Friedrich of the Netherlands" (2nd Westphalian) No. 15 in Minden.

Expeditions and private lectureship in Berlin

Influenced by the First International Polar Year , an initiative of Carl Weyprecht , Franz Boas moved to Berlin in October 1882 to organize his expedition to the Arctic . Boas obtained financial support from the publisher Rudolf Mosse in return for fifteen articles for the Berliner Tageblatt . He also succeeded in gaining scientific support from the physician Rudolf Virchow , the ethnologist Adolf Bastian and the polar researcher Georg von Neumayer . Hermann Wilhelm Vogel introduced him to photography. In addition, Boas learned the basics of the Danish language and Inuktitut , the language of the Eastern Canadian Eskimo .

On June 20, 1883, Franz Boas, accompanied by Wilhelm Weike, set out in Hamburg on his expedition to the Inuit of Baffinland . As a geographically trained scientist, he developed the basics of ethnological field research , based on a cultural-ecological approach. In September 1884, Boas ended the expedition in New York and initially stayed with his fiancée Marie Krackowitzer.

After his return, Franz Boas presented the results of his research trip at the 5th German Geographers' Day . He also presented them in his habilitation thesis on the ice conditions in the arctic ocean . As a habilitation student in the subject of physical geography, he was a research assistant in the ethnographic department of the Berlin Ethnographic Museum .

In the summer of 1885 Franz Boas became a private lecturer at the Friedrich Wilhelms University . In Berlin he met members of the Bella Coola or Nuxalk Indian tribe from British Columbia who had brought Johan Adrian and Fillip Jacobson to Germany.

From 1886 to 1887 he undertook an expedition to British Columbia at his own expense, and in 1888 the British Association for the Advancement of Science supported his north-west coast expedition .

Emigration to the USA

His uncle Abraham Jacobi - emigrated to America because of his activities in the democratic revolution of 1848 - had become wealthy as a pediatrician . He made it possible for Franz Boas to move to the USA in 1886. In 1887, Franz Boas and Marie Krackowitzer married, although he had little income as an employee of the science magazine Science . After his marriage, Franz Boas took on the US citizenship .

In 1892 he became a lecturer in anthropology at Clark University in Worcester. In 1893 he became assistant to the director of the Peabody Museum , Frederick Ward Putnam at the great World's Columbian Exposition . The exhibits came to the Field Columbian Museum in Chicago, where Boas was a curator for 18 months until he was scared off there. He then went on a short expedition to document the Kwakiutl winter ceremony .

From 1896 to 1900 he was assistant scientific director of the anthropological department of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. From 1896 he also taught physical anthropology at Columbia University in New York, and Boas received a professorship in anthropology in 1899, which he held until his retirement in 1936. From this position he succeeded in professionalising American anthropology and expanding ethnology beyond the North American research area. Boas pioneered a new direction in anthropology , cultural anthropology . In 1942, however, he himself only called it a sub-area of ethnology; the investigation of the cultural peculiarities of the societies distinguished by these stood alongside the investigation of body structure and linguistic research.

Leading the Jesup North Pacific Expedition

During his time at the American Museum of Natural History, Franz Boas achieved a top position in US ethnology by planning and directing the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1897–1902). The expedition was able to prove the Asian origin of the North American Indians. Boas also endeavored to safeguard the cultural heritage of the North American Indians and the Eskimos.

Commitment against racism and national socialism

Even before Hitler came to power , he spoke out against racism . Two months later, on March 27, 1933, he protested in an open letter to Reich President Paul von Hindenburg against the anti-Semitism of the National Socialists: “I am of Jewish descent, but I am German in my feelings and thoughts. What do I owe to my parents? A sense of duty, loyalty and the urge to honestly seek the truth. If this is unworthy of a German, if filthiness, meanness, intolerance, injustice, lies are viewed as German today, who else can be a German? "

Boas' works also fell victim to the book burning in Germany in 1933 . This and the restriction of the freedom of research and teaching as well as the persecution of politically dissenting scientists strengthened his rejection of National Socialism and its racial ideology. Boas received many petitions and appeals for help from persecuted German scientists, Jews and non-Jews. In some cases he was able to campaign successfully for their immigration to the USA.

At a banquet in honor of the ethnologist Paul Rivet , who fled France from the German occupiers , Boas suffered a stroke on December 21, 1942 and died. Claude Lévi-Strauss , who had sat next to him, was shocked: He paid tribute to Boas by saying that he had not only seen the old master of his discipline go by, “but the last of the intellectual giants that the 19th century was able to produce and how we will probably never see her again ”.

position

Boas became known for his cultural relativism : Every culture is relative and can only be understood from within. He developed a historical particularism: every culture has its own history and development. One should not try to make a general law about how cultures develop. From 1887 onwards he contradicted the evolutionism of Lewis Henry Morgan and John Wesley Powell for the first time .

He positioned himself early on against the racism that was widespread at the time and also accepted in science . In 1894 he took a public position against scientific racism for the first time in a lecture to the American Association for the Advancement of Science . In the lecture he made it clear that the criterion of race could not stand up to any precise scientific examination and that it was no longer an analytical instrument for anthropology and ethnology . In his work Race, Language and Culture , Boas takes the view that intelligence is not hereditary, but is learned culturally. He criticizes the intelligence tests that were common at the time.

Boas and his students (such as Alfred Kroeber and Ruth Benedict ) had a lasting influence on North American anthropology.

Boas is known for his research into hunting communities of the Indians on the north-northwest coast of the USA. He did research with the Kwakiutl . As he studied it, he noticed the inconsistency in Morgan's theory. Evolutionism claims that hunters and gatherers always represent the lowest stage of development with a hard existence without luxury, on which only daily struggle for survival is waged. But Boas found a completely different situation with the Kwakiutl: Although they are hunters, they are still sedentary. They had a comfortable life with plenty of food from fishing for salmon on the coast. They owned rich pottery and a distinctive handicraft and even prisoners of war from neighboring tribes as house slaves . And they had so much that they could give it away or even destroy it - namely at the potlatch . His research on this gift exchange ceremony has been used extensively by Thorstein Veblen ( theory of demonstrative consumption ) and Marcel Mauss (theory of gift ).

Boas also influenced the French philosopher and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss , who met him several times during his exile in New York in 1942.

Boas' experiences with the Kwakiutl occupied anthropology for many generations. It is thanks to his precise descriptions and records that the Eskimo thread games found their way into the western world.

student

Boas' importance for the still young science of anthropology is also related to the high proportion of his students among the first professional university anthropologists in the USA. From 1901 to 1911 Columbia University produced seven PhDs in anthropology. That number, by its standards, cemented Boas's department at Columbia as an outstanding anthropology program in the country. His students, as well as pupils who were also able to establish anthropological courses at the other major US universities, were:

- Alfred Louis Kroeber (1901) was the first doctoral student; together with his fellow student Robert H. Lowie (1908) he created the anthropological program at the University of California, Berkeley .

- William Jones (1904 PhD from Columbia) was one of the first Native American anthropologists ( Fox ). He was killed in research in the Philippines in 1909 .

- Albert B. Lewis (1907) and Frank Speck (1908), who earned his PhD at the University of Pennsylvania and established an anthropology department there.

- The linguist Edward Sapir (1909) taught at the universities of Berkeley, Ottawa, Chicago and Yale.

- Alexander Goldenweiser (1910) started anthropology at the New School for Social Research together with Elsie Clews Parsons . Parsons received his PhD in sociology from Columbia in 1899; afterwards she studied ethnology with Boas.

- Paul Radin (1911) conducted extensive field research among the Ojibwa and Winnebago Indians in the Great Lakes Region and taught as an ethnologist.

- After his death in 1918, Herman Karl Haeberlin (around 1914) left a total of 41 notebooks, which Boas arranged for them to be published.

- Fay-Cooper Cole (1914) developed the anthropology program for the University of Chicago.

- Esther Goldfrank , married to Karl August Wittfogel since 1940 , traveled to New Mexico with Boas in 1919 to research the Pueblo Indians .

- Leslie Spier (1920) laid the foundations at the University of Washington in Seattle together with his wife and Boas student Erna Gunther. Gunther was able to publish from Herman Haeberlin's notes. They all came from Germany.

- Ruth Benedict (1923), influential representative of the culture-relativistic "culture and personality school", taught at Columbia University until her death in 1948.

- Melville J. Herskovits (1923) taught at Northwestern University in Evanston (Illinois).

- Zora Neale Hurston studied anthropology on a scholarship. She finished her studies in 1928 at Barnard College .

- Margaret Mead (1929) was a staunch advocate of cultural relativism.

- Joseph Harold Greenberg (1932ff.), Founder of the modern syntactic language typology, which received significant impulses from a congress contribution from 1961 ("Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements"). Main proponent of functional syntax theories, who, alongside Noam Chomsky, is considered one of the great American linguists of the second half of the 20th century.

- Gilberto Freyre , Brazilian sociologist, called Boas his teacher.

- Viola Garfield continued work on the Tsimshian , and Frederica de Laguna did research on the Inuit and Tlingit .

Several students were the editors of the American Anthropologist , the publication of the American Anthropological Association : John R. Swanton (1911, 1921–1923), Robert Lowie (1924–1933), Leslie Spier (1934–1938), and Melville Herskovits (1950–1952) .

Memberships

- Burschenschaft Alemannia Bonn from 1877 until the voluntary return of the ribbon in 1935

- Co-founder of the American Anthropological Association

- Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory until its exclusion in 1938 (quote: "Given ... [his] hostile attitude towards Germany today.")

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences (since 1900)

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (since 1903)

- Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (since 1912)

- Corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences (since 1924)

- Member of the Leopoldina Scholars' Academy (since 1927)

Honors

- 1919: Gold medal from the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory .

- 1923: Academic honorary citizen of the University of Bonn.

- 1931: Honorary doctorate from Kiel University on the 50th anniversary of his doctorate.

A plaque with the following text has been attached to Franz Boas' birthplace at Markt 14 in Minden since 2008:

“Franz Boas, the founder of American cultural anthropology, grew up in this house. He was one of the first great [sic!] Field researchers in ethnology and taught as a professor in New York for almost forty years. He emphasized the uniqueness and equality of all human cultures and, out of a lived humanism, fought racist ideologies in the USA and Germany. "

The Human Biology Association presents a Franz Boas Distinguished Achievement Award for outstanding achievements in human biology .

See also

- Eskimo words for snow - Boas' misinterpretation

- Research history of the Indian cultures of North America

- Cultural area

Fonts (selection)

- bibliography

- Klaus-Gunther Wesseling : Boas, Franz . In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL), Vol. 35. Bautz, Nordhausen 2014, ISBN 978-3-88309-882-1 , Sp. 57–122 (the most complete bibliography of Franz Boas's writings to date).

- author

- Baffin land . Geographical results of a research trip carried out in 1883 and 1884 . Perthes, Gotha 1885. ( online )

- Contributions to the knowledge of the color of water . Kiel 1881.

- Language of the Bella Coola Indians . 1886, ( online )

- The Central Eskimo , 1888. (Reprinted from Bison Book, Washington 1967)

- Changing the Racial Attitudes of White Americans. In: George W. Stocking Jr. (Ed.): A Franz Boas Reader - The Shaping of American Anthropology, 1883-1911 . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1982, ISBN 0-226-06243-0 , pp. 316-318.

- The Social Organization and the Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians. In: Report of the US National Museum for 1895. Washington 1897, pp. 311-738. (Reprint: New York 1970, online )

- The creature of the sixth day . Colloquium Verlag, Berlin 1955.

- Growth of Children . 1896-1904.

- Facial Paintings of the Indians of Northern British Columbia , 1898.

- Traditions of the Thompson River Indians of British Columbia , 1898. ( online )

- Tsimshian Texts . Washington 1902.

- Kwakiutl text . With George Hunt, (1858–1933). Leiden 1902-1905.

- The Outlook for the American Negro. In: George W. Stocking Jr. (Ed.): A Franz Boas Reader - The Shaping of American Anthropology, 1883-1911 . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1982, ISBN 0-226-06243-0 , pp. 310-316.

- The Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island . New York 1909.

- The Mind of Primitive Man . 1911. (2nd edition 1938)

- Changes in the Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants. Columbia University, New York 1912.

- Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. In: Thirty-Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. 2 volumes, 1913-1914. Smithsonian, 1921.

- Culture and race . Veit, Leipzig 1914. (2nd edition. Gruyter, Berlin 1922)

- Grammatical Notes on the Language of the Tlingit Indians . University Museum, Philadelphia 1917.

- Kutenai Tales Bulletin 59. Co-author Alexander F. Chamberlain. Smithsonian Institution, Washington 1918.

- Primitive kind . Oslo 1927. (Reprinted in Dover, New York)

- Anthropology and Modern Life . Norton, New York 1928.

- Material for the Study of Inheritance in Man . 1928.

- Race Problems in America. In: George W. Stocking Jr. (Ed.): A Franz Boas Reader - The Shaping of American Anthropology, 1883-1911 . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1982, ISBN 0-226-06243-0 , pp. 318-330.

- The Religion of the Kwakiutl Indians. In: Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology. No. 10, New York 1930. 2 vols.

- Race and culture . Jena 1932.

- A Chehalis text. In: International Journal of American Linguistics . Volume VIII, No. December 2, 1934.

- Aryans and Non-Aryans . Information and Service Associates, New York 1934.

- Race, Language, and Culture . New York 1940 (Collected Articles).

- Dakota Grammar . Together with Ella Delora. 1941.

- Race and Democratic Society . Augustin, New York 1945 (posthumous).

- Kwakiutl Ethnography. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1966. Published by Helen Codere on appointment by Boas.

- editor

- Handbook of American Indian Languages. Bureau of American Ethnology , United States Government Printing Office , 2 Vols., 1911.

- General Anthropology . Heath, Boston 1938.

literature

- Ursula Bender-Wittmann, Jürgen Langenkämper: Franz Boas (July 9, 1858– December 21, 1942). For the 150th birthday. (Series of publications by Münzfreunde Minden und Umgebung No. 25), Minden 2008.

- Norman F. Boas: Franz Boas 1858-1942. An illustrated biography. In Celebration of Franz Boas' 150th Birthday . Seaport Autographs Press, Mystic 2004, ISBN 0-9672626-2-3 .

- Douglas Cole: Franz Boas. The Early Years, 1858-1906. Seattle 1999.

- Regna Darnell: And Along Came Boas. Continuity and Revolution in Americanist Anthropology. Amsterdam / Philadelphia 1998.

- Michael Dürr, Erich Kasten , Egon Renner (eds.): Franz Boas. Ethnologist, anthropologist, linguist. A pioneer of modern human science. Reichert, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-88226-573-6 .

- Roland Girtler: Franz Boas - fraternity member and son-in-law of an Austrian revolutionary from 1848. In: Anthropos. 96 (2001), pp. 572-577.

- Markus Verne: PhD, expedition, habilitation, emigration. Franz Boas and the Difficult Process of Planning a Scientific Life (1881-1887). In: Paideuma , 50 (2004), pp. 79-100.

- Walter Goldschmidt (Ed.): The Anthropology of Franz Boas. The American Anthropological Association, Washington 1959.

- Melville Herskovits: Franz Boas. The Science of Man in the Making. New York 1953.

- Charles King: School of the Rebels. How a group of daring anthropologists invented race, sex and gender . Translated from the English by Nikolaus de Palézieux, Hanser, Munich 2020, ISBN 9783446265806 .

- Alfred L. Kroeber et al. a. (Ed.): Franz Boas, 1858–1942. Menasha 1943.

- Ludger Müller-Wille, Bernd Gieseking (ed.): With Inuit and whalers on Baffin land (1883/1884). Wilhelm Weike's arctic diary. Minden History Association, Minden 2008.

- Friedrich Pöhl, Bernhard Tilg: Franz Boas. Culture, language, race, ways of an anti-racist anthropology. Ethnology: Research and Science, Vol. 19, 2nd edition. LIT, Berlin 2009.

- Volker Rodekamp (Ed.): Franz Boas 1858–1942. An American anthropologist from Minden. Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 1994, ISBN 3-89534-116-9 .

- Ronald Rohner (Ed.): The Ethnography of Franz Boas: Letters and Diaries of Franz Boas, Written on the Northwest Coast from 1886 to 1931. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1969.

- Hans-Walter Schmuhl (ed.): Cultural relativism and anti-racism. The anthropologist Franz Boas. Transcript, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-8376-1071-0 .

- George W. Stocking Jr .: Franz Boas and the Culture Concept in Historic Perspective. In: ders .: Race, Culture, and Evolution. Essays in the History of Anthropology . University of Chicago Press 1982, pp. 195-233. (Free Press, New York 1968)

- George W. Stocking Jr. (Ed., Inlet): The Shaping of American Anthropology, 1883-1911. A Franz Boas Reader. New York 1974.

- George W. Stocking Jr .: The Ethnographer's Magic and Other Essays in the History of Anthropology . University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

- George W. Stocking Jr .: Volksgeist as Method and Ethic. Essays on Boasian Ethnography and the German Anthropological Tradition. 1996.

- Bernhard Josef Tilg, Friedrich Pöhl: Donnerwetter, we speak German! Memories of Franz Boas (1858-1942) . In: Anthropos , Vol. 102 (2007), pp. 547–559.

- Klaus-Gunther Wesseling: Boas, Franz . In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL), Vol. 35. Bautz, Nordhausen 2014 ISBN 978-3-88309-882-1 , Sp. 50–57 and Sp. 57–122 (Bibliography).

Web links

- Literature by and about Franz Boas in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Franz Boas in the German Digital Library

- University of Paderborn: Bibliography.

- Bielefeld University: Workshop 2008.

- Franz Boas biography in the personal dictionary

- The Boas Digitization Project

- The BOAS project

- Utz Maas : Persecution and emigration of German-speaking linguists 1933-1945 . Contribution to Franz Uri Boas (accessed: April 13, 2018)

- Irene Geuer: July 9th, 1858 - birthday of the ethnologist Franz Boas WDR ZeitZeichen on July 9th, 2013. (Podcast)

swell

- Michael Dürr: Various texts on Boas , including the search for “authenticity”. Texts and languages in Franz Boas (1992), pp. 103–124

- Roland Girtler : Franz Boas. (PDF file; 104 kB)

- Alexander Grau: Live as an Eskimo with the Eskimo. .

- Michael Hacker: Franz Boas on the 60th anniversary of his death. (PDF file; 631 kB)

- Jürgen Langenkämper: Family life full of worry and loss . (PDF; 141 kB)

- Robert H. Lowie: Biographical Memoir of Franz Boas 1858-1942. 1947 ( PDF ).

- Mindener Tageblatt: Frozen feet and a hot heart ( Memento from February 12, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- City of Minden: The Boas Project.

- City of Minden: Gender book Heinemann (Chajim) / Boas. (PDF file; 69 kB)

Individual evidence

- ^ Gender book Heinemann (Chajim) / Boas , franz-boas.de, accessed on April 6, 2018.

- ↑ Alfred Desbrosses: Descendants list Krackowizer Simon ; here: KRACKOWIZER Marie Anna Ernestine

- ↑ Douglas Cole: Childhood and youth of Franz Boas. Minden in the second half of the 19th century. Communications from the Mindener coating association, year 60 (1988), pp. 111-134.

- ^ The Jesup North Pacific Expedition 1897-1902 led by Franz Boas, the first landmark research project of the Division of Anthropology was financed by Museum president Morris Ketchum Jesup

- ↑ Uwe Carstens : Franz Boas' "Open Letter" to Paul von Hindenburg. In: Tönnies forum . Volume 16, issue 2/2007, pp. 70–75 (there also Ferdinand Tönnies ' answer).

- ↑ Georg W. Oesterdiekhoff (Ed.): Lexicon of sociological works. Springer Fachmedien, 2nd edition, Wiesbaden, 2013, p. 78 f.

- ↑ Edith Hirte: To see is to know? - Franz Boas and American anthropology at the World`s Coulbian Exposition. In: Hans-Walter Schmuhl (Ed.): Cultural Relativism and Anti-Racism - The Anthropologist Franz Boas (1858-1942). transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, 2009, pp. 20-23.

- ↑ Bernhard Tilg: Franz Boas` opinions on the issue of "race" and its commitment to the rights of African Americans. In: Hans-Walter Schmuhl (Ed.): Cultural Relativism and Anti-Racism - The Anthropologist Franz Boas (1858-1942). transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, 2009, pp. 85-87.

- ↑ Samuel Salzborn (Ed.): Classics of the Social Sciences - 100 key works in portrait. Springer VS Fachmedien, Wiesbaden 2014, pp. 128–131.

- ^ Curtis M. Hinsley, Jones, William ... (1871-1909). In: Frederick E. Hoxie (Ed.): Encyclopedia of North American Indians. 1996, p. 308f.

- ^ Letter from chairman Carl Schuchhardt to Boas, quoted from: Hermann Pohle and Gustav Mahr (eds.): Festschrift for the centenary of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory 1869–1969. First part: Technical historical contributions. Heßling, Berlin 1969, p. 130.

- ^ Member History: Franz Boas. American Philosophical Society, accessed May 8, 2018 .

- ^ Boas Award - Human Biology Association. In: humbio.org. Accessed February 24, 2017 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Boas, Franz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-American ethnologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 9, 1858 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Minden |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 21, 1942 |

| Place of death | new York |