Women's suffrage in South Asia

The women's suffrage in South Asia , so in the states of Afghanistan , Bangladesh , Bhutan , India , the Maldives , Nepal , Pakistan and Sri Lanka , has no uniform development. The different religions, dealing with the colonial past as well as different epochs of political turmoil and armed conflict influenced the development. When it was first introduced, women's suffrage was often linked to conditions such as proficiency in reading and writing or a certain level of ability, so that women were allowed to vote, but not under the same conditions as men. Sri Lanka was one of the first countries in Asia and Africa to achieve women's suffrage.

Investigation of possible influencing factors on the political representation of women

religion

In the former colonies with a large Islamic population, such as Pakistan, there was a tendency to associate women's emancipation with the West and thus with the colonial rulers. In the decolonization phase, this gave rise to an effort to reject women's emancipation in order to be able to assert their national identity.

Sri Lanka had a background similar to India, but was subject to significant Buddhist influence. The Buddhism admits a high priority to women. This led to a more extensive literacy of women than in countries with other religions, which was the basis for a stronger self-confidence of women and had a positive effect on the development of women's suffrage.

Merits of women in the struggle for independence

As in Finland, in India the achievement of women's suffrage is to be seen in connection with the commitment of women in the struggle for independence. Before independence, women had limited voting rights.

Nationalistic ideas from other countries

The influence of Indian nationalist ideology on neighboring countries meant that in some countries, such as Sri Lanka , women gained the right to vote even earlier than in India.

Leading the way for remote areas

At the subcontinental level, the example of Sri Lanka and other neighboring states of India confirms that women's suffrage was achieved earlier in more remote areas that were not politically central than in areas where there was a highly developed political culture.

Male suffrage

In 1912, middle-class men were given the right to vote in Sri Lanka, and this, as in Europe, encouraged women to demand the right to vote for their own kind on the same terms as men.

War and new constitutions

War and the subsequent drafting of new constitutions often brought about the introduction of women's suffrage, regardless of the new orientation of the state: in India it was a liberal democracy, while in Burma there was violence and political turmoil.

Individual states

Afghanistan

In 1923, Amanullah Khan proposed a new constitution that included voting rights for women. Proposals for reform such as the abolition of veils and the improvement of educational opportunities for women met with opposition from the tribal chiefs, whose power was based on strict control. They deposed Amanullah Khan in 1929 and reversed the reforms: Nader Shah and Zaher Shah canceled the women-friendly measures, girls' schools were closed, the veil became compulsory and women were not allowed to vote.

In the constitution of 1963, which provided for a constitutional monarchy and came into force in 1964, women were given the right to vote and stand for election and exercised it for the first time in 1965. But it was limited to women who could read and write; this restriction was later lifted. The first election of a woman to the National Parliament of Afghanistan took place in July 1965.

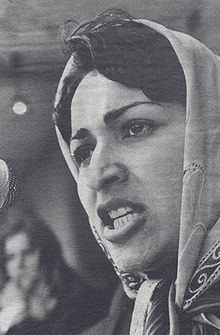

After this election there were unstable times for democracy and in 1973 the king was deposed and with the help of the Soviets, who were pursuing their own interests in Afghanistan, a republic was proclaimed; there were no political parties. But the future of the country was discussed in public and feminists like Meena Keshwar Kamal were able to organize. After the Soviets withdrew in 1989, the country was left to the heads of military gangs until the Taliban victorious in 1996 . In these turbulent times, the prevailing opinion was that traditional Afghan values should be upheld, western powers pushed back and women's suffrage should be rejected as an attribute of western democracy. Under the auspices of the United Nations, the summit of Afghan women for democracy took place in December 2001, at which equal rights for the sexes, including the right to vote, were demanded. Education was seen as the key to equality: after the fall of the Taliban government in 2001, girls 'schools were reintroduced, but the fundamentalists fought them, so that by the end of 2006 there were entire provinces without girls' schools. The Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan RAWA continued its struggle for a secular government. Great efforts have been made to register women for the 2004 presidential election; More than four million women signed up, making up 41 percent of the 10.5 million registered. As a sign of willingness to make a public declaration of equality for women, 25% of the seats were reserved for women in the 2005 general election.

Bangladesh

In 1937, the Government of India Act , which had been passed in 1935, entered into force, giving the right to vote for literate women who had an income and paid taxes. When Pakistan became an independent rulership in 1947, this right was confirmed and also applied to Bangladesh, then East Pakistan . In 1956, when Bangladesh was still part of Pakistan, women were given universal suffrage.

In 1971, as a result of the separation of East Pakistan from Pakistan, Bangladesh gained independence. On November 4, 1972, a new constitution was passed and put into effect in December 1972, which guaranteed universal suffrage for all citizens aged 18 and over.

In the national parliament, 300 seats are allocated by election, 50 more ( only 45 before the Fifteenth Amendment Act , which was passed by parliament on June 30, 2011) are reserved for women. They are allocated to the parties in accordance with the proportion of votes obtained in the elections; the candidates they have selected are confirmed by parliament (as of 2016).

First election of a woman to the national parliament: March 1973.

Bhutan

In 1953 women were given limited voting rights at the national level: there was only one vote per household. Only new legal regulations ( Royal Decree of June 30, 2007, Election Act of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008, Public Election Fund Act of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008, a new constitution that was adopted by Parliament on July 21, 2008) guaranteed Universal suffrage. At the local level, only one vote per family is allowed (as of 2007), which means that in practice women are often excluded from voting.

Passive women's suffrage: 1953

First election of a woman to the national parliament: 1975

India

According to reports from 1900, the participation of women in local elections in Bombay was made possible with an amendment to the Bombay Municipal Act (1888): Homeowners could then vote regardless of gender. There are indications, however, that some women voted in the Bombay city council elections many years in advance.

In 1918 the Indian National Congress supported the introduction of active women's suffrage, and the constitutional reforms of 1919 allowed the legislative assemblies in the provinces to decide on the introduction. Madras Province, in which the Anti-Rahman Party had a majority, was the first to give women the right to vote in 1921; other provinces followed. Women who had the right to vote at the provincial level were also allowed to vote in the elections to the Central Legislative Assembly.

In 1926 women were also given the right to stand as a candidate. In 1926, Sarojini Naidu became the first female Congress President.

The British MP Eleanor Rathbone campaigned for women's suffrage and on May 5, 1933 founded the British Committee for Indian Women's Franchise , which represented eleven women's organizations. It served as a platform for the politician who saw access to education and political life for Indian women as the way to progressive enlightenment . She urged Indian women to give up their demand for universal suffrage and advocated limited women's suffrage that required literacy and did not even apply to all wives. She was also in favor of reserving certain parliamentary seats for women.

These restrictions were heard in the reform of the franchise: In 1935, the Government of India Act , which came into force in 1937, further extended the right to vote for both sexes. It stipulated that women could vote if they met one of several conditions: real estate, a certain level of education that included reading and writing, or the status of a wife if the man was eligible to vote. The amendment of another provision indicated an important shift in understanding what was meant by civil rights: some seats in the legislative assemblies of the provinces were reserved for women; Men could not take on these mandates. These rules guaranteed that women were actually elected. The rule also meant that women applied for mandates beyond this quota, and ensured that capable women could demonstrate their skills as members of parliament and ministers. In 1937 the first elections took place under these new rules. Of the 36 million eligible voters, six million were women. In some provinces only wives could vote, in others women who could read and write or were married to an officer, and there was always a separate quota for women in the electorate. Of the 1,500 seats awarded in the provincial elections, only 56 were women.

By the end of 1939, all provinces had given women the right to vote. Although this was a fundamental step forward, the right to vote was tied to land ownership. Since many Indians did not own land, relatively few men and even fewer women were given the right to vote as a result of the 1919 reforms.

India gained independence in 1947. Until then, there had been no universal suffrage for either women or men. As in Finland, in India the achievement of women's suffrage is to be seen in connection with the commitment of women in the struggle for independence.

In 1949 the Constituent Assembly drafted a new constitution. Female MPs who had themselves benefited from the quota system spoke out against the continuation of this practice. The new constitution, which came into force on January 26, 1950, provided universal suffrage for all adults. But in the parts of the country that became Pakistan when it was partitioned, women had to wait years for universal suffrage.

Passive women's suffrage: January 26, 1950

First election of a woman to the national parliament after independence: April 1952

Maldives

Women were granted the right to vote in 1932 under colonial administration. It was confirmed upon independence in 1965.

Woman's First Election: Colonial Legislative Body: Two Women, January 1, 1953. Post-Independence National Parliament: One Woman, November 1979.

Nepal

Active and passive women's suffrage: 1951

In 1952 women had already been appointed to parliament. The first election of a woman to the national parliament, Dwarika Devi Thakurani , took place on October 21, 1951. She was the only woman among the 109 members of the House of Commons. In the same elections, a woman was appointed to the House of Lords, which had 36 members.

Pakistan

In 1937 women were granted national voting rights, but it was tied to reading and writing skills, income and taxation.

In 1946, in the first election based on the Government of India Act of 1919 , women were allowed to vote under certain conditions. The conditions applied to very few women. Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah was elected to the United Constituent Assembly of India in 1946, before Pakistan split off. However, because of the ongoing clashes, the Muslim League ordered that its members should not take the seats in the assembly. In 1947 Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah and Jahanara Shah Nawaz were elected to the national parliament.

After independence in August 1947, the Government of India Act of 1935 became the Constitution of Pakistan. Certain women were able to vote on this basis in provincial and national elections.

When a new constitution was being discussed in the 1950s, it was suggested that all men should be given the right to vote, but only educated women. There were tendencies towards Islamization. For example, the dictator Mohammed Zia-ul-Haq did not want to deprive women of the right to vote, but did want women in civil service to have full body veils.

On March 23, 1956, Pakistan's first constitution was passed, providing for universal active and passive voting rights for adults aged 21 and over at all levels if they had lived in the country for six months. Women thus received full voting rights in 1956. However, no election was held under this constitution because of the difficulties between civil and military powers.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka was one of the first countries in Asia and Africa to achieve women's suffrage. At the subcontinental level, the example of Sri Lanka confirms that women's suffrage was obtained earlier in more remote areas that were not politically central than in areas where there was a highly developed political culture. Indian nationalist ideas gained a foothold in Sri Lanka and contributed so much to the development that Sri Lanka introduced women's suffrage before India. Sri Lanka had a background similar to India, but was subject to significant Buddhist influence. The Buddhism admits a high priority to women. This led to a more extensive literacy of women than in countries with other religions, which was the basis for a stronger self-confidence of women and had a positive effect on the development of women's suffrage.

Sri Lanka had been ruled by the British since 1815. Towards the end of the 19th century, an indigenous middle class and working class emerged, and they soon demanded political rights. In 1912, middle-class men were given the right to vote, and this encouraged women, as in Europe, to demand the right to vote for their own kind on the same terms as men.

In 1927, a women 's franchise union was founded, supported primarily by educated women, many of whom worked in education, including in prominent positions.

The British asked Lord Donoughmore to head a commission that would prepare and initiate a reform process in Sri Lanka. He was an advocate for women's rights in education. The commission recommended voting rights restricted to women over 30. But the constituent assembly went even further: the Donoughmore constitutional reforms of 1931 introduced the right to vote for women over the age of 21 on March 20, 1931. This was in line with the legal regulation that had been introduced in Great Britain three years earlier.

When independence was achieved in 1948, active and passive voting rights for women were confirmed.

Passive women's suffrage: March 20, 1931

Since then, however, women have only been represented in a very small number on political bodies. Of the members of the legislative assembly at the national level, they never made up more than 4% of the members, and participation at the level of the local governing bodies was also insignificant.

First election of a woman to the colonial parliament (Senate): Adlin Molamure , November 14, 1931; in the national (House of Representatives): Florence Senanayake , August 1947

See also Elections in the British Crown Colony of Ceylon

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 412.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 350.

- ↑ a b c Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 349.

- ↑ a b c d e Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 351.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 372.

- ↑ a b c Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 416.

- ↑ Kumari Jayawardena: Feminism and nationalism in the Third World. Zed Books London, 5th Edition 1994, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved September 29, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 2.

- ↑ a b c d Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 419.

- ↑ a b Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 420.

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved September 30, 2018 .

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 222.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 28.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. January 13, 2016, accessed September 28, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. July 21, 2008, accessed September 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Inter-Parliamentary Union: IPU PARLINE database: BHUTAN (Tshogdu), Electoral system. In: archive.ipu.org. June 30, 2007, accessed September 25, 2018 .

- ↑ Pamela Paxton, Melanie M. Hughes, Jennifer Green: The International Women | s Movement and Women's Political Representation, 1893-2003 . In: American Sociological Review, Volume 71, 2006, pp. 898-920, quoted from Pamela Paxton, Melanie M. Hughes: Women, Politics and Power. A global perspective. Pine Forge Press Los Angeles, London 2007, p. 62.

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 40.

- ^ A b Gail Pearson: Tradition, law and the female suffrage movement in India. In: Louise Edwards, Mina Roces (Ed.): Women's Suffrage in Asia. Routledge Shorton New York, 2004, pp. 195-219, pp. 199.

- ↑ a b c d Kumari Jayawardena: Feminism and nationalism in the Third World. Zed Books London, 5th Edition 1994, pp. 99-100.

- ↑ a b c d e f Gail Pearson: Tradition, law and the female suffrage movement in India. In: Louise Edwards, Mina Roces (Ed.): Women's Suffrage in Asia. Routledge Shorton New York, 2004, pp. 195-219, p. 196.

- ↑ a b c d Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 348.

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 139.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 346.

- ^ Gail Pearson: Tradition, law and the female suffrage movement in India. In: Louise Edwards, Mina Roces (Ed.): Women's Suffrage in Asia. Routledge Shorton New York, 2004, pp. 195-219, p. 196.

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 139.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 175.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 178.

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 247.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Accessed October 4, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 272.

- ↑ a b - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. October 21, 1959, accessed October 5, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 273.

- ↑ a b c - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved November 6, 2018 .

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 296.

- ^ A b c June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , pp. 221-222.

- ↑ a b Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 411.

- ^ Robin Morgan: Sisterhood is Global: The International Women's Movement Anthology. New York: Anchor Press / Doubleday, 1984, p. 525.

- ↑ London Diary: DONOUGHMORE RECORDS ON CEYLON-CONSTITUION AUTIONED IN LONDON. In: infolanka.com. June 27, 1996. Retrieved November 11, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c Kumari Jayawardena: Feminism and nationalism in the Third World. Zed Books London, 5th Edition 1994, pp. 128-129.

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 357.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. March 20, 1931, accessed October 6, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 358.