Stuttgart main cemetery

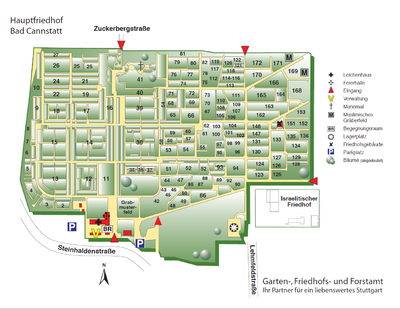

The main cemetery in Stuttgart was opened on January 28, 1918 during the First World War. With an area of 29.6 hectares and 15,000 grave sites, it is the second largest cemetery in Stuttgart. The cemetery is divided into over 120 sections.

A large, old tree population, partly laid out in avenues, gives the cemetery the character of a landscape park. On the cemetery grounds there are several cemetery buildings, an underground storage hall, a pergola dome and movable seating, as well as fountains and water points.

There are grave fields for aviation victims of the Second World War, for victims of euthanasia murders and for Eastern European forced laborers, as well as community graves as well as an Armenian and a Muslim burial ground. A separate Israelite cemetery is attached to the cemetery.

location

The main cemetery in Stuttgart is located in the Muckensturm district of the Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt district . After the Steinhaldenfeld district, which is almost directly adjacent to the main cemetery in the north, the cemetery is also called Steinhaldenfriedhof. The cemetery was opened in 1918 with an area of 6 hectares and expanded five times between 1955 and 1986, up to the current total area of 29.6 hectares. It is the second largest Stuttgart cemetery after the forest cemetery Stuttgart with 30.7 hectares.

The cemetery has the shape of a lying rectangle and extends in an east-west direction. The area of around 470 × 700 meters is divided into over 120 departments with the numbers 2 to 172 (the numbering is incomplete). In the west and at the main entrance in the southwest, the cemetery is bordered by Steinhaldenstrasse, in the north by fields on Zuckerbergstrasse, in the east by Ziegelbrennerstrasse and in the south by Sophie-Döring-Strasse and Thekla-Kaufmann-Weg. At the main entrance, the cemetery is about 280 meters above sea level and rises to about 295 meters to the northeast.

The cemetery is criss-crossed by a checkerboard network of wide main paths and narrower side paths. The main paths are laid out as avenues:

- The main avenue and the chestnut avenue are both lined with chestnut trees.

- Lindenallee and Eastern Lindenallee are flanked by linden trees planted in 1879.

- A maple avenue runs from the cemetery building to the Israelite cemetery.

- A wide, short avenue of false cypress trees begins behind the cemetery building.

- A wide, short avenue of beech trees extends from the stairs that lead down from the "Fliegerfeld Memorial" to the western edge of the cemetery.

In addition, some conifer species and many different types of deciduous trees are scattered all over the cemetery area.

Cemetery building

In 1913, the city of Stuttgart announced a competition to design the cemetery complex and the cemetery buildings for a new, large main cemetery. The Stuttgart architects Ludwig Eisenlohr and Oscar Pfennig won first prize and were entrusted with the implementation. Because of the outbreak of the First World War, construction work was only carried out between 1916 and 1919. The original design was reduced in size due to the circumstances of the time, in particular the planned church building was omitted.

The floor plan of the one-story main building at Steinhaldenstrasse 52 is in the shape of a "d". The four wings of the building with hipped roofs and dormer windows are grouped like atrium around a rectangular courtyard, the right wing (at the entrance) being around 20 meters longer than the opposite wing. An arched gallery on the front side of this wing, together with the white plastering of the facades, gives the building a southern flair. Ten gray cast concrete columns with ornamental capitals support the arches of the arcades.

The celebration hall and a meeting room are housed in the long wing. The north transverse wing serves as a morgue, and the rooms in the other wings are intended for the administration and management of the cemetery. The caretaker's house to the right of the cemetery entrance at Steinhaldenstrasse 50 was built as a one-story building with a hipped roof and dormers.

To the north of Department 133 there is a large, modern covered hall with seating and toilets. The building, which is open on the sides, consists of an apparently floating tent roof, which is supported at the four corners with massive extensions in the ground. At department 62 there is an airy rest area with benches in a large pergola. Two square water basins could increase the effect of this oasis of calm if they weren't drained.

| → More photos |

|

|

|

|

Burial grounds

In the cemetery there are grave fields for the aviation victims of the Second World War, for the victims of euthanasia murders and for Eastern European forced laborers who died in Stuttgart. Two further grave fields are reserved for the burial of the Armenian and Muslim dead.

Aviation victim

A sign near the celebration hall refers to the “Ehrenfeld Fliegeropfer”. If you follow the main avenue to the end, you will find section 41 with three memorials and over 1,300 memorial plaques for the aviation victims. The memorial was designed and inaugurated in 1956 according to the plans of the Stuttgart landscape architect Käthe Haag. The site is dedicated to the aviation victims of World War II, particularly the 1,459 victims who were killed in the bombing on the night of September 12, 1944.

The three memorials are designed as circular areas with a diameter of around 10 meters, which are arranged next to each other at 10 meters intervals. The floor of the memorials is laid out concentrically with gray stone slabs. In the middle there is a raised round plate, the middle memorial with the relief of a sign of the cross, the left memorial with the inscription "The victims from a difficult time" and the right memorial with the years 1940 to 1945. The middle memorial is made of three stone Circle segments surround. They bear the inscription “Our Missing” and 136 inscriptions with the names and life dates of missing air victims.

The fields above and below the memorials were originally covered with a grid of over 1,300 round memorial plaques, many of which have now disappeared. The plates bear the names and dates of life of an individual, around two dozen larger plates are dedicated to several people.

Euthanasia victim

The main avenue of the cemetery begins at the main entrance by the celebration hall and ends at departments 40 and 41. The large department 41 is known as the “Ehrenfeld Fliegeropfer”. The small department 40 is not marked by name, in contrast to the “Ehrenfeld Fliegeropfer” there are no signposts to the department (the same applies to the grave fields of the forced laborers and the Armenians).

The division 41 has the shape of a narrow, lying rectangle. If you enter it at the top right corner, you will come across a massive gray stone cube. The cube has a side length of about one meter and bears the names of eight Nazi killing centers as inscriptions: Grafeneck, Hadamar, Hartheim, Sonnenstein, Brandenburg, Buchenwald, Dachau and Bernburg.

A staircase with three steps leads down to a regularly laid out field of sunbathing plates that takes up a quarter of the department. A low wall confronts the visitor with the inscription “The Victims of Violence”. The burial ground consists of 34 memorial plaques made of shell limestone. Each plate bears the inscriptions, some of which are difficult to read, with the names and the year of birth and death of eight deceased.

The cemetery contains the urns of 271 euthanasia victims . On the website of the city of Stuttgart, under the keyword "main cemetery", one does not find out anything about the cube and the burial ground of department 40. A search for "euthanasia" on the website of the city of Stuttgart does not lead to any result, but a Google search for " Hauptfriedhof Stuttgart Euthanasia "finds a well-hidden note from the city:

- “In the main cemetery there is a field of honor for 271 victims of the Nazi murder of the sick (so-called euthanasia). Ceremony on November 12, 1962. Between 1940 and 1942, around 380 urns were sent to the cemetery office from the killing centers used for the murder. In the case of around 100 deaths, relatives were identified and the urns were handed over. The remaining urns were buried in a grave field with 271 urns, the names of which are written on 34 limestone blocks. "

Slave labor

In the upper left corner of the cemetery there is a two-part burial ground for Eastern European forced laborers. The northern, larger part of the cemetery is occupied by the tree-lined section 26. There are 20 memorial stones for up to 360 forced laborers on the field, scattered irregularly. Each memorial stone bears the names and life dates of up to 18 people who died between 1941 and 1945 on the front and back.

The slave laborers to whom the memorial stones are dedicated were euphemistically referred to as "Eastern workers" in the Nazi language, a term that was sometimes used unknowingly even after the Nazi era. Between the memorial stones there are also two small gravestones for two Polish babies who were buried here in 1948.

Below department 26 is in department 24 and to the right of it in department 21 on the side of the road, the second part of the cemetery with 9 memorial steles for around 200 Eastern European forced laborers. One of the steles bears the Russian cross on the four sides, as a sign that Russian Orthodox believers are buried here. The remaining 8 steles bear 8 inscriptions on three sides each with the names and life dates of buried forced laborers.

Similar to the cemetery for the euthanasia victims, there is no reference or explanation for the cemetery of the Eastern European forced laborers. A search for the term “forced laborers” on the website of the city of Stuttgart yields the succinct result: “Memorial for the forced laborers - main cemetery”. A Google search for "Hauptfriedhof Stuttgart Zwangsarbeiter" yields the sparse sentence: "In the main cemetery, a field of honor commemorates the forced laborers who perished in Stuttgart."

|

|

|

Armenians

Towards the end of 1944, in view of the advance of the Red Army, many Armenians from eastern Germany came to Stuttgart and were employed there as slave labor. In October 1945 the American military authorities left the radio barracks in Bad Cannstatt to Armenian and Ukrainian displaced persons ("homeless foreigners"). At times up to 3,000 Armenians and around 150 Ukrainians were housed in the buildings. In 1950 the last residents left the barracks.

An Armenian cemetery was opened in Department 15 during the Second World War in 1944 to bury the Armenian dead. In section 15b, around 50 tombs from the 1940s and 1950s have been preserved, mostly in poor condition due to their age. The burial ground is still used for the burial of citizens of Armenian origin. In 1987, the Council of the Armenian Apostolic Church Baden-Württemberg had a cross stone ( Chatschkar ) erected as a memorial in the upper left corner of Department 15b . The cross stone bears the inscription: "In memory of the victims of the Armenian people".

|

|

|

Muslims

In 1985, a Muslim burial ground for around 700 grave sites was laid out in sections 169 and 171. The two triangular areas are on the northeastern edge of the cemetery along a path that runs diagonally to the northeast. Muslims who have died have been buried here since 1986.

The journalist Eva Funke reported in the Stuttgarter Nachrichten in 2012 that at that time only about 35 Muslims were buried in the main cemetery every year. Around 90 percent of Stuttgart's Muslims were buried in their Turkish homeland because not all Islamic burial rituals are allowed in Stuttgart and because the burial costs in Stuttgart are more than twice as high as the costs for the transfer to Turkey and the burial there.

According to the Islamic burial rite, the tombs face Mecca. The design of the individual graves is based on the respective faith of the deceased. The graves have a headstone, a stone or wooden stele or a wooden plaque with inscriptions in Latin and Arabic script, more rarely with a photo of the deceased. The leveled or slightly raised burial mounds are framed by a low grave border made of white pebbles or stone slabs or fenced with a low wooden fence or metal railing. The burial mound is rarely covered with a stone slab. The graves have no or only natural vegetation, are covered with white stones and are rarely decorated with flowers and other plants.

| → Muslim graves (photos) |

|

|

|

|

Tombs

Some graves are designed as community facilities. Lawn graves are reserved for urn burials, other communal graves are intended for burial in the ground or for urn burials.

Lawn diggers

Lawn graves are urn graves on designated lawns of the cemetery in divisions 75, 78 and 82 ( photo ). Certain rules apply that take into account the park-like character of the cemetery. The graves are marked by a square stone with the names and dates of the deceased.

Community graves

Community graves are grave fields that offer space for several earth or urn graves and whose care is taken care of by commissioned stonemasons and cemetery gardeners or an organization. These include the following tombs:

- The grave complex in Department 39 consists of three roundels with urn community graves, which are grouped within an outer roundabout. This is surrounded by tall trees and edged with a hedge. Two of the inner roundels have three yellow stone steles of different heights in their middle. The third inner roundabout is lined with circular gray stone steles, the upper edges of which form a wavy line.

- In Department 55 there is a grave of the Red Cross Sisters ( photo ). A massive stone cross with the inscription “I am the resurrection and life” stands at the top of the uniformly designed bedplate graves, to the left and right of the cross there are four collecting plates with the names and dates of life of about 80 sisters.

- The grave complex in Department 77a consists of 9 low, desk-shaped memorial stones with the names and dates of life of up to 12 deceased ( photo ). The stones stand in a semicircle around a lawn, in the middle of which rises the head-high bronze sculpture of a germinating plant.

- A curved path runs through the grave complex in Department 90, which widens in the middle to form a lenticular island ( photo ). The stele-like tombstones are grouped near and on the island.

- In Department 133, by the large under-standing hall, there is a uniformly designed system with graves on a bed plate for deaconesses ( photo ). A high steel cross rises on a square of lawn within the facility.

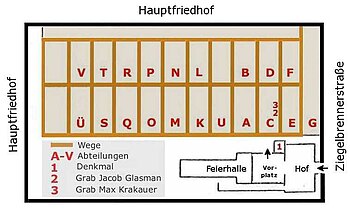

Israelite cemetery

The Israeli Cemetery, a rectangular burial ground of around 1.5 hectares, is located in the southeast of the main cemetery on an area separated by high hedges at 23 Ziegelbrennerstraße (map:) . The cemetery was laid out between 1938 and 1940 because there was a shortage of space in the Israelite section of the Prague cemetery. The celebration hall was built in 1939, rebuilt in 1946 and 1962. Jewish burials have taken place almost exclusively in this cemetery since 1945.

![]()

The grave fields are in sections A to V, which extend between the southern and northern connecting paths. The graves were usually occupied in the order of the department letters. The earliest graves are in Division A and Division U. The letter U stands for urn grove, to distinguish the division between T and V divisions was given the letter Ü. In the 1940s, around a dozen people were buried in the urn grove without a tombstone. She is remembered by a simple brick with her name and date of death.

On the facade of the celebration hall, to the right of the entrance, there is a simple memorial plaque ( photo ), which commemorates the 6,000,000 victims of the Holocaust. A wide staircase leads from the forecourt of the celebration hall to the cemetery departments. In a grove-like corner on the right is a memorial to the victims of the Shoah . A black stone stele bears the inscription “In memory of the Jewish fallen and victims of the Shoah 1933–1945” in German and Russian on the front, and the Hebrew and English translations on the reverse. The end of the stele is formed by a stylized seven-armed candlestick ( menorah ) made of gray stone.

| → More photos |

|

|

|

|

Graves

| → Column legend and sorting | ||||||||||

| Legend | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Sorting | ||||||||||

Main cemetery

| Illustration | # | P | K | dig | * | † | object |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

11 | P | Willi Bleicher , trade unionist and Nazi resistance fighter. | 1919 | 1981 | ||

| - | K | Dimitry Kosmowicz , Belarusian Nazi collaborator | 1909 | 1991 | |||

| - | P | Karl Marx , composer, grave cleared (2017). | 1897 | 1985 |

Israelite cemetery

| Illustration | # | P | K | dig | * | † | object |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

C. | K | Jacob Glasman. | 1912 | 2003 | Plastic representation of the city of Jerusalem. | |

|

|

C. | K | Max and Ines Krakauer . | 1888 | 1965 |

Funerary art

| → More photos |

|

|

traffic

The U2 and U19 trams stop at the “Hauptfriedhof” stop (200 meters to the cemetery), just before the tunnel that crosses under the cemetery. The next stop is "Zuckerberg" (350 meters to the cemetery).

literature

graveyard

- Johann Friedrich Häuselmann: Consultation room. The main cemetery competition in Stuttgart. In: Competitions. Competition news. Supplement to the German competitions number 255 from October 23, 1913, pages 1537–1539.

- Werner Koch, Christopher Koch: Stuttgart cemetery guide. A guide to the graves of well-known personalities. , Silberburg, Tübingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8425-1203-0 , pages 150–151.

- A. Neumeister (editor): Main cemetery in Stuttgart. In: German competitions united with architecture competitions Volume 29, 1913, issue 11, pages 1–31.

- Annette Schmidt: Ludwig Eisenlohr. An architectural path from historicism to modernity. Stuttgart architecture around 1900. Stuttgart-Hohenheim 2006, pages 556–561, 143.

- Sibylle Schwenk: Cannstatt Secrets. Against forgetting. In: Stuttgarter-Zeitung.de, January 2, 2015, online .

Others

- Elmar Blessing: The prisoners of war in Stuttgart: the municipal prisoner of war camp on Ulmer Strasse and the “Gaisburg disaster” . Stuttgart: Verlag im Ziegelhaus, 1999, especially pages 61–66, 70–73.

- Eva Funke: Instead of being in the coffin, only in the shroud to eternal rest. In: Stuttgarter-Nachrichten.de, May 10, 2012, [2] .

- Joachim Hahn: Cemeteries in Stuttgart, Volume 3: Pragfriedhof. Israelite part. Stuttgart 1992.

- (lin): The history of the Theodor-Heuss-Kaserne. In: Stuttgarter Nachrichten, April 7, 2011, online .

- Azal Ordukhanyan: The Armenian Displaced Persons in Germany after the Second World War. In: Armenuhi Drost-Abgarjan (editor); Hermann Goltz (editor): Armenology in Germany: Contributions to the First German Armenologist Day. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2005, pages 219–232, partial view .

- Searching for traces of victims of the National Socialist murders, stolpersteine-stuttgart.de, “Euthanasia” working group .

Web links

- Main cemetery on the website of the city of Stuttgart.

Footnotes

- ↑ #Mammut 2011 .

- ↑ #Neumeister 1913 , # Häuselmann 1913 .

- ↑ # Schmidt 2006 .

- ↑ #Schwenk 2015 .

- ^ Website of the city of Stuttgart .

- ^ Website of the city of Stuttgart . - See also # Hahn 1992 , pp. 20-21.

- ^ Website of the city of Stuttgart .

- ^ Website of the city of Stuttgart .

- ↑ #Ordukhanyan 2005 , pp. 223, 225, #lin 2011

- ↑ [1] .

- ↑ #Funke 2012 .

- ↑ #Mammut 2011 .

- ^ Website of the city of Stuttgart .

- ↑ #Hahn 1992 , page 18th

- ↑ photo

- ↑ #Koch 2012 , pp. 150–151.

Coordinates: 48 ° 49 ′ 13 " N , 9 ° 14 ′ 6.7" E