Lockheed Have Blue

| Have blue | |

|---|---|

Have Blue prototype "HB1001" |

|

| Type: | Stealth plane |

| Design country: | |

| Manufacturer: | |

| First flight: |

1st December 1977 |

| Number of pieces: |

2 |

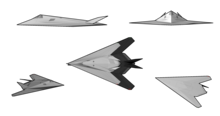

Have Blue was the code name of a top-secret program for the development of a stealth aircraft by the special development department Skunk Works of the US manufacturer Lockheed . The F-117A Nighthawk emerged from the two test vehicles Have Blue Experimental Survivable Testbed (XST) .

history

background

The origins of the F-117 can be traced back to 1974. It was then that DARPA , a new technology research organization for the US armed forces, began studying aircraft as part of the Harvey project (the name is an ironic reference to the invisible rabbit that accompanies James Stewart in the movie My Friend Harvey ) with a low probability of detection. Various companies should investigate how large the radar cross-section (RCS) of a fighter aircraft can still be in order to ensure survival in enemy airspace with a high air defense threat. DARPA asked Fairchild-Republic, General Dynamics, Grumman, McDonnell Douglas and Northrop , but Fairchild and Grumman immediately canceled due to insufficient engineering capacities. General Dynamics believed that reducing the RCS alone would not be enough to meet DARPA's expectations. However, it strictly refused to include additional measures for active radar interference in the investigations. General Dynamics then withdrew from the program.

As the last remaining companies, Northrop and McDonnell Douglas each received a contract worth 100,000 US dollars. The technical requirements were very high when you consider that to reduce the detection range of an aircraft by 90%, its RCS must be reduced by a factor of 10,000. Previous attempts to reduce the RCS only led to a reduction of 50%, which in real use had a hardly noticeable effect on the detection range.

Lockheed had not been invited to participate in this program because production of the last tactical fighter aircraft developed, the F-104, had ceased ten years earlier. When Clarence Johnson , Lockheed's chief developer, became aware of the DARPA program, he clearly pointed out to DARPA the experience already made with the SR-71 and A-12 with regard to reducing the radar cross-section. After the concept proposed by McDonnell Douglas relied too heavily on active measures to jam the enemy radar, DARPA withdrew the company from the study program.

For Phase I of the subsequent Experimental Survivable Testbed (XST) program, DARPA officially selected the remaining companies Lockheed and Northrop on November 1, 1975. Both first built full-scale wooden models of their designs for examinations in a radar test facility and in a wind tunnel. For the radar tests, the models were placed on a high pile structure at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. The tests showed a slight advantage for the Lockheed proposal in terms of radar assessment, which together with the know-how and experience gained from the previous Black Projects in the processing of composite materials led to Lockheed's success.

Have blue

In April 1976 Lockheed was awarded a contract worth 19.2 million US dollars for Phase II of the XST program, the construction of two airworthy Have-Blue prototypes, to demonstrate the practical feasibility of the concept. In phase II, project support changed from DARPA to the US Air Force (USAF), which imposed a very high level of confidentiality on the project, so that practically no information about the further development was made public. The two demonstration aircraft received neither the official USAF designation nor USAF serial numbers, internally they were designated as HB1001 (BLUE-01) and HB1002 (BLUE-02). The designations XST-1 and XST-2 were also common. The first flight of HB1001 took place on December 1, 1977 at the test site at Groom Lake in Nevada . The machine was lost on May 4, 1978 on its 36th flight after damage to the landing gear. On landing, the right rear wheel did not extend completely. The pilot, Lockheed's test pilot Bill Park, tried to shake it out of the shaft with flight maneuvers , but failed. Then he got out of the ejection seat , injuring himself and having to give up his job. The second machine flew for the first time on July 20, 1978. Without the externally attached measuring devices, which were still used on the HB1001, this aircraft could practically not be detected by airborne radar. Only the Boeing E-3 AWACS was able to detect it from a short distance. During the 52nd flight, a fire broke out on board after hydraulic damage, whereupon the pilot had to disembark Lt. Col. Dyson. The total cost of the Have Blue program was $ 43 million for both aircraft, of which Lockheed itself contributed $ 10 million.

During all test flights, care was taken to ensure that there were no spy satellites over the region; all staff without access to Have Blue were sent to the windowless mess of the base so that they could not catch a glimpse of the aircraft. The prototypes were covered in the hangar when they were not being worked on.

The test results of the Have Blue program prompted William Perry , then Secretary of State for Research and Engineering (Defense Under-Secretary for Research and Engineering), to urge the Air Force to use stealth technology on an emergency aircraft. In 1980 Secretary of Defense Harold Brown announced accordingly that the Carter administration had increased spending on stealth projects by a factor of 100. Most of the funds went into the development and production of a fully operational stealth fighter, code-labeled Senior Trend , which later became known as the Lockheed F-117 .

designation

The name Have Blue was created according to the specifications of the directive CJCSM 3150.29, whereby the first term Have is permanently assigned to the Air Force Systems Command (AFSC), while the second part of the name could apparently be chosen at will.

construction

The prototypes were 14.4 m long with a 6.8 m span. They were powered by two General Electric J85 -GE-4A jet engines without afterburner with 13.1 kN thrust each , which were removed from a decommissioned North American T-2 B Buckeye. This enabled the machines to reach approx. 970 km / h. To speed up production, many more parts were used that were already in use on other aircraft. For example, the landing gear of an A-10 was used, the instruments from an F-5 . The fly-by-wire control system comes from an F-16 , but had to be adapted because the Have Blues were designed to be unstable around all three axes. The first prototype had a conventional pitot tube for measuring speed . Since this pitot tube increased the radar reflectivity of the aircraft, the second prototype did not have such a measuring system. Furthermore, the planes had no weapon bays.

See also

literature

- Dennis R. Jenkins, Tony R. Landis: Experimental & Prototype US Air Force Jet Fighters , Specialty Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-58007-111-6 , pp. 230-234

- David Donald (Ed.): Black Jets - The Development and Operation of America's Most Secret Warplanes , AIRtime Publishing, 2003, ISBN 1-880588-67-6 , pp. 62-73

- David C. Aronstein: Have Blue and the F-117A - Evolution of the "Stealth Fighter." American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 1997, ISBN 1-56347-245-7 .

- Steve Pace: Lockheed Skunk Works (Chapter 16) , Motorbooks International, 1992, pp. 219-226

Web links

- The Have Blue / F-117 story (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Black Jets, p. 8, AirTime Publishing

- ↑ Jim Goodall: F-117 Stealth in action , squadron / Signal publications aircraft No. 115, p. 5

- ↑ Code Names for US Military Projects and Operations on www.designation-systems.net

- ↑ Code names beginning with H on www.designation-systems.net