Imervard Cross

The Imervard Cross in Brunswick Cathedral is one of the most important Romanesque sculptures on German soil. It is named after the otherwise unknown master Imervard , who signed it by name.

Description and art-historical classification

description

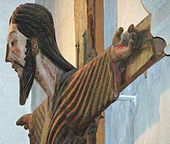

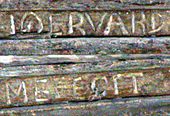

The Imervard Cross, created towards the end of the 12th century, is a larger than life crucifix made of oak with a height of 2.71 m and a width of 2.66 m . It shows Christ crucified in the manner of a four-nail cross . He is portrayed as victor and king, not suffering and dying. The body is erect, with arms protruding horizontally. Long nails form the connection between the cross and the crucified one, so that he hovers more in front of the cross than hangs on it. Hands and feet are disproportionately large. The upper body is turned frontally towards the viewer, the head tilted slightly downwards to the left. He is dressed in a long sleeve robe, the tunica manicata . A long belt is attached around the waist, the ends of which hang down symmetrically. It is shifted slightly to the right and is not directly on the central axis of the body . Here is also the signature of the carver: Imervard me fecit. This was originally covered by a gold fitting.

The robe with the folds looks axially symmetrical at first glance. On closer inspection, it becomes apparent that there are eleven folds on the left arm, but only ten on the right. The folds, which extend from the torso to the trunk, are passed under the belt and only partially continued correctly (not all folds were continued). The protruding head, like the hands and feet, is shown overstretched. The neck appears narrow and fragile. As in the Volto Santo type , the eyes are wide open and brown, the pupils no longer exist. The eyelids droop heavily over the wide-open eyes and are enclosed by high, forcibly raised eyebrows. Nose folds, mustache and corners of the mouth are pointed and run almost parallel.

The upper lip is advanced and is in front of the lower lip and chin. The flat hair falls straight back to the nape of the neck and is parted in the middle. The whiskers leave the chin free and lie on top of each other like a wing under the chin. Just like the rest of the statue, the outlines of the head appear angular and severe. The thickness of the sculpture is sometimes only 3 cm. The entire body is kept very flat and carved out of several parts. This becomes particularly clear at the interface between the arms and the torso.

Colored version

During restoration work it was found that in the original version only the belt was covered with goldsmith work. The original form of the robe was purple , with a green undergarment visible in the neckline. The trims of the sleeve tunic still show slight traces of gold.

Reliquary

In the back of the crucified Christ's head, not visible from the front, there is a reliquary deposition - a cavity that encompasses the entire back and can be closed by a sliding lid. The entire sculpture thus served as a grand reliquary . The 30 relics originally contained in it were removed in 1881 and placed in the reliquary vessel of a column of the Marian altar , where they are still today.

Date of origin

The research does not agree on the time of origin because there are no sources. What is certain is that the Imervard Cross must have been created after the Grand Cross of Lucca (in Tuscany ), as there are direct links between the two in terms of shape and iconography. The clothing of the crucified Christ with a sleeved tunic and the ancient rigidity of the garment make it possible that it was created around the year 1000. On the basis of historical comparisons, however, the time of origin is more likely to be in the middle of the 12th century. Dating to the time after 1174 is questionable, even if this could be suspected based on the presence of a Thomas Becket relic . The high number of relics found in the body of the crucifix could point to an origin during the reign of Henry the Lion , who brought a large number of relics with him from his travels. Later dating would be possible, but cannot be proven.

Current condition

Like most of the surviving sculptures from the Romanesque period, the Imervard Cross has not survived the last 850 years without traces. The colored design is no longer available in its original form and has been changed several times over the years. Today the cross is presented in a brown frame, the undergarment still has its original green color. Toes and fingers are partly broken off, as are strands of beard and hair. It is believed that the cross used to be wider. In addition, it can be assumed that there was originally a gold diadem on the head, as there is a nail hole in the vertex.

Volto Santo influence

In today's art history research it is assumed that the Imervard cross relates directly to the Volto Santo type ("Holy Face"). It therefore belongs to a group of grand crosses that originated mainly in Italy, Spain, France and England and all refer to the original form of the legendary cross in the Cathedral of San Martino in Lucca, Italy. If one compares the works with one another, the similar basic concept is noticeable: “The Son of Man (Revelation Joh. 1,13) becomes in his dual nature as a man who died on the cross and who reigns in eternity with arms outstretched in a flowing splendid robe with a golden belt Cross shown ". The changes that Master Imervard made are characteristic of the style will of the Romanesque: creation of a pure symmetry through alignment on the central axis, stretching and sharpening of all forms.

From the weight of the cross and the lack of brackets and handles, it can be concluded that it was probably not a processional cross .

Master Imervard

The unknown master Imervard, who probably created the cross named after him around 1150, marked his work on the ends of Christ's belt with the inscription IMERVARD ME FECIT (“Imervard made me”). This marking was originally hidden from the viewer by a cover on the belt made of sheet gold. To this day there is no further reference to the name and sphere of activity of this master of Romanesque visual arts. His name, which is likely to be of Northern European origin, i.e. possibly Low German , Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian , is nowhere else in art history. Due to the similar design language, it would be possible that Master Imervard also created the famous Braunschweig lion .

Installation site

Old documents indicate that the cross was still in the cathedral's crypt in the middle of the 17th century . Several decades later, namely in 1861, it was "found" in the tower vault and then hung in the apse of the northern transverse arm.

Today it is in the place where it was hung in 1956 - the east wall of the outer north aisle.

Others

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Braunschweig uses the Imervard Cross in its logo.

literature

- August Fink: The Imervard Cross and the Triumphal Cross of Henry the Lion for the Brunswick Cathedral. in: Braunschweigisches Magazin. 1925, pp. 65-71.

- Reiner Haussherr: The Imervard Cross and the Volto Santo type. In: Journal for Art History. 16/1962, pp. 129-180.

- Hermann Leber: The Imervard Cross. 19XX

- Jochen Luckhardt , Franz Niehoff (ed.): Heinrich the lion and his time. Rule and representation of the Guelphs 1125–1235. Exhibition catalog, 3 volumes, Munich 1995.

- Eugen Lüthgen: Romanesque sculpture in Germany. Bonn 1923, pp. 158-160.

- Cord Meckseper (Ed.): City in Transition. Art and culture of the bourgeoisie in Northern Germany 1150–1650. Exhibition catalog, 4 volumes, Stuttgart 1985.

- A. Quast: The St. Blaise Cathedral in Braunschweig: its history and his works of art. Braunschweig 1973, pp. 36-38.

- Harmen Thies : The cathedral of Heinrich the Lion in Braunschweig: building and works of art. Braunschweig 1994, pp. 54-56.

Web links

- Information about the Imervard Cross on braunschweigerdom.de, the official website of the Braunschweiger Cathedral

- Information about the Imervard Cross on insschriften.net

Individual evidence

- ↑ Reiner Haussherr: The Imervard Cross and the Volto Santo type. in: Journal for Art History. 16/1962, p. 129.

- ↑ Fink 1949: As the restorer of the Imervard Cross, Mr. Herzig in Braunschweig, kindly informed me, during the restoration he only found golden nails, which suggest gilding of the affected areas, in the belt.

- ↑ A. Quast: The St. Blaise Cathedral in Braunschweig: its history and his works of art. Braunschweig 1973, p. 38.

- ↑ a b c A. Quast: The St. Blaise Cathedral in Braunschweig: its history and his works of art. Braunschweig 1973, p. 36.

- ↑ Eugen Lüthgen: Romanesque sculpture in Germany. Bonn 1923, p. 160.