James Hemings

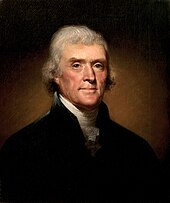

James Hemings (* 1765 in Guiney , Virginia Colony , † 1801 in Baltimore , Maryland ) was an American chef . In addition to George Washington's head chef Hercules, Hemings is one of the chefs of the US founding fathers with African American roots. James Hemings is responsible for the fact that its long-time owner, later US President Thomas Jefferson , is said to have introduced both French and Black African elements into American cuisine .

Hemings was one of the slaves who came into the possession of Thomas Jefferson when he married Martha Wayles . He was a slave-born child of John Wayles , father of Martha Wayles. His sister Sally Hemings later became Jefferson's lover and like her, Hemings accompanied Jefferson to Paris when he was residing there as the American ambassador. Hemings was trained there by various French chefs at Jefferson's instigation. Separately, Hemings took language classes to learn the French language.

He and Jefferson returned to the United States when he was appointed Secretary of State and worked for Jefferson in Philadelphia, then the capital of the United States. Hemings managed to persuade Jefferson to release him from slavery. He was given his freedom in 1796 after training his brother Peter for almost three years to replace him as head chef of the Jefferson household. Hemings committed in 1801 at the age of 36 years suicide .

Life

family

James Hemings was the son of Elizabeth "Betty" Hemings. This in turn came from the British naval captain John Hemings and from Susannah, an African woman who had been enslaved and sold to the USA.

James Hemings was the second child born out of Betty Heming's relationship with her owner, John Wayles. Wayles made Betty Hemings, then 26, his lover after he was widowed a third time. A total of six children came from this relationship, most of whom had white people as ancestors. Betty Hemings had four older children from a previous relationship with another man. Since their mother was a slave, all of these children were also slaves according to the legal principle of partus sequitur ventrum applied in Virginia , which had been in force since 1662.

John Wayles died in 1773, leaving both Betty Hemings and her ten children to his daughter Martha, her half-sister. Martha Wayles married Thomas Jefferson a little later, who came into the possession of these ten people.

Like his mother and siblings, James Hemings was one of the so-called "house slaves" who worked as servants in the manor house. Hemings worked in the kitchen and was so clever at it that Jefferson decided to take the then 19-year-old with him to Paris. Hemings embarked with Jefferson on July 4, 1784 in Boston, and on August 6 of the same year they reached Paris.

In Paris

Hemings came to Paris at a time when a new restaurant culture was emerging here. Until well into the 18th century, the catering trade in soup kitchens , pastry bakers and other guilds was strictly separated. Since 1782 this strict separation had also been abolished by law. However, individual people had already succeeded in establishing a restaurant as it is today. Various contemporary sources before 1800 name Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau as the first restaurateur in Paris to open his restaurant in 1766. Restaurants established themselves very quickly, serving their guests dishes that were previously only consumed in noble houses.

Hemings had an unusual status in France: According to the French view, he was free here because France limited slavery to its colonies. However, the relevant French laws were complex and often contradictory. There were also a number of slaves in Paris, the majority of whom were people who accompanied their owners when they returned to France from the French colonies. Although their number was small, it was increasing steadily, so that attempts were made in France to limit the length of stay of such persons. The number of black people in Paris at the time Hemings came there was around 1,000, including many freedmen with white parents. There was even an elite within this group: these included the violin virtuoso Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges and the French general Thomas Alexandre Dumas . Jefferson paid Hemings a salary in France, probably because of the difficult legal status, and Hemings was hardly restricted in his freedom of movement according to today's knowledge.

Hemings received further training from various cooks and bakers in Paris at Jefferson's instigation. Meals were still served “ à la française ”: a large number of very different dishes were offered on a table covered with white linen, around which the guests sat. As a rule, the individual guests only ate from the dishes that were placed in their vicinity by the service staff. At least one elaborately prepared and decorated dish was cut up by the host or the guest of honor and distributed among those present. The challenge for the chef was to serve a combination of attractive and visually appealing dishes at the same time. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that this form of dinner was increasingly replaced by the so-called " service à la russe ", in which the dishes were portioned in the kitchen and increasingly a waiter served the individual guest. Hemings also learned to cook on the “potager”, a forerunner of today's kitchen stoves, in which the individual hotplates were individually heated. This newly developed oven allowed the cook to control the heat more carefully and led to the development of a number of new dishes. Jefferson was so taken with this new type of kitchen stove that years later he had one built in Monticello. This type of stove did not catch on in the United States, however, and the "Potager" on Monticello remained one of the few examples of this stove type. In 1788, Hemings became head chef at Jefferson's residence on the Champs-Elysées .

It is not clear why Hemings did not use his opportunities in Paris and freed himself from slavery. He could read and write, had learned French of his own accord and, given his professional skills, would have been able to find work elsewhere. George Washington's head chef, Hercules , chose this route around ten years later. In the case of Hemings, it may have played a role that the rest of the family still lived on Jefferson's family home in Monticello. In 1789 he returned to the USA with Jefferson and his sister Sally Hemings .

Back in the USA

Hemings worked for Jefferson briefly in Monticello, Virginia, where slavery was legal, and then in New York and Philadelphia, where slavery was abolished. As before in Paris, Jefferson Hemings paid a salary there. When it was time to return to the slave state of Virginia in 1793, Hemings finally asked Jefferson for his release. Jefferson granted it to him, but made the release conditional on Hemings training another slave as a cook. In a letter that had no binding force, but morally obliged Jefferson, the latter stated:

“After I had James Hemings trained in the art of cooking at great expense, and out of the desire to remain a friend to him and to ask as little as possible from him, I hereby promise and declare that James will join us this winter I should return to Monticello, where I will live in the future, and that there he will train a person, whom I will report to him, to be a good cook. If he has met these conditions, he will be released afterwards and I will take all reasonable steps to give him this freedom. "

Hemings trained his brother Peter on Monticello. In her analysis of Afro-American cuisine, Jessica Harris names this a typical development for the Hemings family. Many members of this family worked in the kitchen of Jefferson's Monticello mansion for a very long time, so that Harris speaks of a kitchen dynasty in relation to this family.

In 1796, the education of Heming's brother Peter was so advanced that Hemings was released. On February 26, 1796, Hemings left Monticello to go to Philadelphia. Jefferson had given Hemings $ 30 for his first expenses. Hemings first lived in Philadelphia and then began to travel. He may have visited Spain, among other places, but ultimately settled in Baltimore.

Thomas Jefferson was elected President of the United States by the House of Representatives after an aggressive election campaign along with his Vice President -elect, Aaron Burr of New York . In 1801 Jefferson contacted Hemings and offered to become the head chef of his presidential household. Hemings initially accepted this offer, but requested a formal letter in which Jefferson explained his exact duties to him. Jefferson's refusal to have such a letter drafted ended with Hemings declining the post. The position went to the French Honoré Julien. Had Hemings accepted the position, he would have been the first African American to head a US president's kitchen.

Hemings returned to Monticello, where he had been offered the post of head chef of the local household. However, he did not take up this position either, but worked for a few months in a bar in Baltimore . Hemings is said to have drank too much alcohol and committed suicide in delirium that same year .

Aftermath

The Jefferson-Randolph family cookbooks contain two recipes that are known to have been written by James Hemings. These two recipes are desserts that are influenced by French cuisine: chocolate cream and snow eggs . The cookbooks also feature recipes that are in an African American tradition. These include catfish and peanut soup and a Virginia gumbo . However, Heming's authorship cannot be proven for these.

The Library of Congress also holds the kitchen inventory that Hemings wrote down before he left Monticello in 1796.

literature

- Jessica B. Harris: High on the hog: a culinary journey from Africa to America. Bloomsbury, New York 2011, ISBN 978-1-60819-127-7

Single receipts

- ↑ a b c Harris: High on the hog . P. 77.

- ↑ Berkes, Anna; et al .: John Wayles . Monticello Foundation. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ↑ James Hemings . In: monticello.org . Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ↑ "John Wayles" , Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia , Monticello, access from July 5, 2015

- ↑ a b Harris: High on the hog . P. 78.

- ↑ Petra Foede: How Bismarck got hold of the herring. Culinary legends. Kein & Aber, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-0369-5268-0 , pp. 178-182.

- ^ Rebecca L. Spang: The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture . Cambridge 2000, p. 251.

- ↑ a b c Harris: High on the hog . P. 79.

- ↑ Nichola Fletcher: Charlemagne's Tablecloth - A Piquant History of Feasting . Phoenix Paperback, London 2004, ISBN 0-7538-1974-0 , pp. 155-157

- ↑ a b Harris: High on the hog . P. 80.

- ↑ a b c d Harris: High on the hog . P. 81.

- ↑ Harris; High on the hog . S. 81. The original quote is: Having been at great expence [sic] in having James Hemings taught the art of cookery, desiring to befriend him and to require from him as little as possible, I do hereby promise & declare, that if the said James shall go with me to Monticello in the course of the ensuing winter, when I go to reside there myself, and shall there continue until he shall have taught such person as I shall place under him fort hat purpose tob ea good cook This previous condition being performed, he shall be thereupon made free, and I will thereupon execute the proper instruments to make him free.

- ↑ RB Bernstein: RB Bernstein: Thomas Jefferson. Oxford University Press, New York a. a. 2005, ISBN 0-19-518130-1 . P. 132

- ↑ a b c High on the hog . P. 82.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hemings, James |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Slave and head chef to Thomas Jefferson |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1765 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Guiney , Virginia Colony |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1801 |

| Place of death | Baltimore , Maryland |