Ushinawareta Nijūnen

Ushinawareta Nijūnen ( Japanese 失 わ れ た 20 年 , eng . "Two lost decades") describes the economic stagnation in Japan , which began with the bursting of the bubble economy in the early 1990s and continued during the period of great price decline. The original name was Ushinawareta Jūnen ( Japanese 失 わ れ た 10 年 , German "Lost Decade") and referred to the 1990s. Since the economic development was also very weak from 2000 to 2010, there was also talk of the two lost decades.

prehistory

One factor behind the price bubbles was the closure of the Japanese market from imports, which in the 1950s served to build up the Japanese economy in a protected zone . By the mid-1980s, however, the Japanese economy was internationally competitive on a broad front, and inflated domestic prices served to subsidize exports . Due to the vertical structure of the Japanese economy, the producers exerted direct influence on the retail chains belonging to their group, and price agreements between the individual conglomerates ( keiretsu ) kept prices at a consistently high level. In almost all areas, the market was divided between three or four large suppliers, and for some products, such as orange juice , a single supplier had the monopoly. Until the late 1980s, which were consumer goods -prices in Japan rose sharply and amounted to some six times of comparable prices in the United States and Europe .

Due to Japan's large foreign trade surpluses, the US government urged that traditional trade barriers be removed. The appreciation of the yen agreed in the 1985 Plaza Agreement exacerbated the situation, as massive capital flowed into the Japanese real estate and stock markets and drove up prices. The yen appreciated 73% from 1985 to 1988.

Bubble boom (1985–1990)

The Japanese refer to the bubble economy from around 1985–1990 as Baburu Keiki ( Japanese バ ブ ル 景 気 , German for “bubble boom”).

In line with the global trend, the financial market in Japan was also deregulated in the 1980s. Japan was particularly poorly prepared for these easing, as the lending of the house bank to "her" Keiretsu was strongly influenced by cliques and not so much by credit checks. Lending to ordinary citizens was also very loose, as the banks hoped that the state would intervene in the event of major bad investments. As a result, the economic bubble assumed extreme proportions: in 1990, the market capitalization (the total quoted value of all stocks) of Japanese companies was three times the market capitalization of companies listed on American stock exchanges, even though the gross domestic product of the United States was more than twice as high. There was a real estate bubble in the mid-1980s . So z. For example, house prices in Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto tripled between 1985 and 1990. In 1990 the Japanese central bank raised interest rates to prevent the economic bubble from growing any further. That was when deflation began.

Big drop in prices (since the 1990s)

The Japanese use Kakaku Hakai ( Japanese 価 格 破 壊 , eng. "Price Destruction") to describe the deflation that began following the decline of the bubble economy . General deflation began in 1994 and has persisted to this day (as of 2016). The consumer price index in 2010 was at the same level as in 1992. The GDP deflator fell by 14% during this period. Real estate prices began to fall as early as 1990 and in 2014 are still below their highs of 1990. Between 1990 and 1995 the yen again appreciated significantly against the US dollar, sending the Japanese economy into stagnation and deflation. In the period that followed, there was only low growth in labor productivity and a weakening of private consumer spending and investment. Economic growth stagnated.

Globalization and the growing economic power of the tiger states and China also put the Japanese price cartels under pressure. As early as the end of the 1980s, there were the first countermovements against the price bubbles: On the one hand, Japanese companies outsourced their production to Southeast Asia in order to escape the wage level in Japan; on the other hand, retail chains for re- imports of Japanese goods, especially electronics and household appliances, were established in the Bought up abroad in order to deliver them to the end user in Japan , at prices well below those usual in Japan. After the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 1990s, purchasing power and the will of consumers to continue to bear the high prices collapsed. Discount chains were the first to benefit from this new trend nationwide. Through direct imports from other Asian countries and bypassing the previous Japanese trade structures, they were able to undercut the prices far. The beginning trend towards discounts and low prices was given the name Kakaku Hakai . Traditional Japanese retail chains tried to keep up by offering goods in their own discount house brands. In 1995 the trend had advanced so far that the government was faced with the question of either leaving the previous trade structures to collapse or deregulating them in order to give the established chains the opportunity to defend themselves against the new competition. In fact, it had no choice but to withdraw further from the economy and leave price regulation to the mechanisms of the market.

Explanatory approaches

Expiry of the catch-up effect

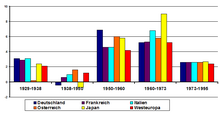

The significant decline in productivity growth can in part be explained by the expiry of the catch-up effect . The catch- up thesis put forward by economic historians Angus Maddison and Moses Abramovitz in 1979 is represented today by numerous economists (including William J. Baumol , Alexander Gerschenkron , Robert J. Barro and Gottfried Bombach ). The catching-up thesis indicates that by 1950 the USA had achieved a clear productivity lead over the European and Japanese economies. After the war, both the European and Japanese economies started a catch-up process and benefited from the catch-up effect. The companies there were able to follow the example of American companies. Figuratively speaking, the catching-up process took place in the slipstream of the leading USA and thus allowed a higher pace. After the productivity level of the American economy had been reached and the catching-up process had come to an end, the European and Japanese economies stepped out of the slipstream, so that such high growth rates as during the post-war boom were no longer possible.

Strong appreciation of the yen

Some economists emphasize that it was part of Japanese economic policy for decades to keep the yen undervalued in order to bring industrial production to the greatest possible expansion through foreign trade surpluses and the resulting consequences ( export multiplier ). A side effect of foreign exchange accumulation through constant foreign trade surpluses is the glut of savings . According to Akio Mikuni and Taggart Murphy, the banks had increasing difficulties investing money profitably.

According to Maurice Obstfeld , Robert Dekle and Kyoji Fukao, there is a strong correlation between the appreciation of the yen in the periods from 1985 to 1988 and from 1990 to 1995 and the loss of international competitiveness . The strong appreciation of the yen caused a sharp increase in the relative cost of production. The core industries were only able to reduce the relative production costs gradually through improvements in labor productivity, so that the relative production cost level of 1985 was not reached again until 2004. Other industries such as the textile and wood industries have not recovered to this day.

External crises

The recovery of the Japanese economy was repeatedly thrown back by external crises such as the Asian crisis (1997–98) or the dot-com bubble (2000). From 2004 onwards, Japan experienced normal economic growth of between 2% and 3%. The global economic crisis from 2007 onwards led to a global recession.

supporting documents

- ↑ Satyajit Das, The Setting Sun - Japan's Decline and Fall, Wilmott, 2013, Issue 65, pp. 10–17, May 2013, doi : 10.1002 / wilm.10213

- ↑ Boye De Mente, Japan's Cultural Code Words: Key Terms That Explain the Attitudes and Behavior of the Japanese , Tuttle Publishing, 2011, ISBN 9781462900626 , keyword: Kakaku Hakai

- ↑ Boye De Mente, Japan's Cultural Code Words: Key Terms That Explain the Attitudes and Behavior of the Japanese , Tuttle Publishing, 2011, ISBN 9781462900626 , keyword: Kakaku Hakai

- ↑ Maurice Obstfeld, Time of Troubles: The Yen and Japan's Economy, 1985-2008 , p. 5, also in: Kōichi Hamada, AK Kashyap, David E. Weinstein, Japan's Bubble, Deflation, and Long-term Stagnation , MIT Press, 2011, ISBN 9780262014892 , p. 51 ff

- ↑ Boye De Mente, Japan's Cultural Code Words: Key Terms That Explain the Attitudes and Behavior of the Japanese , Tuttle Publishing, 2011, ISBN 9781462900626 , keyword: Kakaku Hakai

- ^ Paul Krugman, Die neue Wirtschaftskrise , Campus Verlag GmbH, 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-38933-2 , pp. 75, 80-82

- ↑ Boye De Mente, Japan's Cultural Code Words: Key Terms That Explain the Attitudes and Behavior of the Japanese , Tuttle Publishing, 2011, ISBN 9781462900626 , keyword: Kakaku Hakai

- ^ W. Miles Fletcher III, Peter W. von Staden, Japan's 'Lost Decade': Causes, Legacies and Issues of Transformative Change , Routledge, 2014, ISBN 9781317977025 , Chapter: The Age of Deflation

- ↑ Maurice Obstfeld, Time of Troubles: The Yen and Japan's Economy, 1985-2008 , p. 58, also in: Kōichi Hamada, AK Kashyap, David E. Weinstein, Japan's Bubble, Deflation, and Long-term Stagnation , MIT Press, 2011, ISBN 9780262014892 , p. 51 ff

- ↑ Nikolai Genov, Global Trends and Regional Development , Routledge, 2011, ISBN 9781136633478 , p. 216

- ↑ Boye De Mente, Japan's Cultural Code Words: Key Terms That Explain the Attitudes and Behavior of the Japanese , Tuttle Publishing, 2011, ISBN 9781462900626 , keyword: Kakaku Hakai

- ↑ Naomi N. Griffin, Kazuhiko Odaki, Reallocation and productivity growth in Japan: revisiting the lost decade of the 1990s , in: Journal of Productivity Analysis, Issue 31, No. 2 (April, 2009), pp. 125-136, here p. 133

- ↑ Ludger Lindlar: The misunderstood economic miracle. 1st edition. Mohr Siebeck, 1997, ISBN 3-16-146693-4 , p. 85.

- ^ Karl Gunnar Persson, An Economic History of Europe , Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-54940-0 , pp. 110 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Wagener : The 101 most important questions - business cycle and economic growth. CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59987-3 , p. 33.

- ↑ Akio Mikuni, R. Taggart Murphy, Japan's Policy Trap: Dollars, Deflation, and the Crisis of Japanese Finance , Brookings Institution Press, 2004, ISBN 9780815798767 , introduction

- ↑ Maurice Obstfeld, Time of Troubles: The Yen and Japan's Economy, 1985-2008 , pp. 3, 58, also in: Kōichi Hamada, AK Kashyap, David E. Weinstein, Japan's Bubble, Deflation, and Long-term Stagnation , MIT Press, 2011, ISBN 9780262014892 , p. 51 ff

- ↑ Robert Dekle, Kyoji Fukao, The Japan-US Exchange Rate, Productivity, and the Competitiveness of Japanese Industries , also in: Kōichi Hamada, AK Kashyap, David E. Weinstein, Japan's Bubble, Deflation, and Long-term Stagnation , MIT Press , 2011, ISBN 9780262014892 , p. 105 ff

- ^ International Monetary Fund , Murtaza H. Syed, Kiichi Tokuoka, Kenneth Kang, “Lost Decade” in Translation: What Japan's Crisis Could Portend about Recovery from the Great Recession , 2009, ISBN 9781451918434 , p. 6

- ↑ Murtaza H. Syed, Kiichi Tokuoka, Kenneth Kang, "Lost Decade" in Translation: What Japan's Crisis Could Portend about Recovery from the Great Recession , International Monetary Fund, 2009, ISBN 9781451918434 , pp. 6-8