Childhood and Adolescence in Samoa

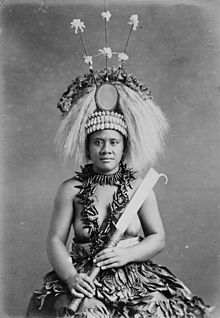

Childhood and Adolescence in Samoa (English original title: Coming of Age in Samoa ) is a monograph by the American ethnologist Margaret Mead . It is based on her research on adolescence, especially the adolescence of girls on the Samoan island of Ta'u . Mead delves into the details of adolescent sexual behavior in Samoan society in the early 20th century. In it, she clarifies her view that it is primarily cultural conditions and not biological foundations that determine the psychosexual development of young people.

The publication in 1928 made Mead the most famous ethnologist of her time. The monograph became the most widely read ethnological book up to Napoleon Chagnon's Yanomamö: The Fierce People. To this day it is the subject of scientific discussions and is considered a standard work of the culture-nature controversy , as well as for topics of family sociology, adolescence and gender research, social norms and attitudes.

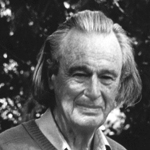

In the 1980s, anthropologist Derek Freeman challenged Mead's research approach, methods, and results. For his part, Freeman's criticism was rejected by the majority of ethnologists as one-sided and inaccurate.

The first German edition appeared in 1970 as Volume 1 of the three-volume Margaret Mead edition Youth and Sexuality in Primitive Societies in the German paperback publishing house .

content

Preface

In the foreword, Mead's mentor Franz Boas writes :

Courtesy, humility, good manners, compliance with certain ethical standards are universal, but what they mean is not universal. It is instructive to learn the unexpectedly different ways in which standards differ from one another.

Boas thought Mead's study was important because people in the United States had already begun to discuss the characteristics of puberty. Boas was convinced that a comparison with other cultures would be illuminating. In the past, puberty was viewed as a natural phenomenon that people had to endure and cope with in order to eventually grow up.

introduction

Mead begins with a general discussion of the problems faced by adolescents in modern society and the various explanations from religion, philosophy, pedagogy and psychology. She sees the perspective of ethnology as a promising alternative to understanding social structures and processes. In order to find the greatest possible contrast to European culture, she chooses the South Seas as the point of reference for her study of adolescence.

She defined her goal as follows:

I wanted to answer the question that sent me to Samoa: are the tremors that plague our youth due to the very nature of growing up or to civilization? Does adolescence look different in different conditions?

To answer this question, she examined a small group of Samoan women in a small village of 600 people on Ta'u Island. She spent there between 6 and 9 months and observed 68 young women between 9 and 20 years of age. She examined everyday life, upbringing, the order of social life and its dynamics, its rituals and rules of behavior.

Life and education

In the first chapter, Mead begins by describing a typical day in Samoa. Then she analyzes the upbringing of the young children. The birth is celebrated with a long ritual festival. After the birth, however, the children are mostly ignored, the girls even in a ritualized manner. It describes the forms of punishment and discipline, which are mostly symbolic. From an early age, children should do activities that are important to society. As they get older, the boys should become more involved in fishing and the girls more involved in raising children. The age does not play a decisive role, rather the physical development of the child.

Mead describes some specific skills the children need to learn related to weaving and fishing, then almost casually inserts the first description of sexuality in Samoa. In addition to working for teenage girls, "all of her [extra] interest is directed to clandestine sexual adventures." This comes right after a passage in which Mead describes that a reputation for being lazy can be very damaging to a growing girl's reputation which implies that for Samoans, work ethic is a more important criterion for marriage than virginity.

Male adolescents are encouraged and punished in various ways in order to make them ambitious and aggressive. Men have many different possible tasks (e.g. "house builders, fishermen, speakers, wood carvers") in the community in which they can prove themselves. Your status results from the balance of efficiency and performance and humble demeanor. In addition, "the social standing is increased by his amorous heroics."

For the growing girl, on the other hand, the status depends mainly on the future spouse. Mead describes growing up and the time before marriage as the high point of a Samoan girl's life. Mead writes:

The seventeen-year-old girl doesn't want to get married, not yet. It is better to live as a girl with no responsibility and a diverse experience. This is the best time of his life.

The household

The next section describes the structure of a Samoan village: "A Samoan village consists of about thirty to forty households, each of which is headed by a head". Each household is an extended family with widows and widowers. The households share the houses together: each household consists of several houses, but no member owns the possession or permanent residence of a particular building. The houses may not all be in the same part of the village.

The head of household has ultimate authority over the group. Mead describes how the extended family gives Samoan children security. Children are likely to be around relatives no matter where they are, and any missing child is quickly found. The household offers freedom to children, including girls. According to Mead, if a girl is not happy with the relatives she is living with, she can always easily move to a different house within the same household. Mead also describes the various and rather complex status relationships that are a combination of factors such as: B. the role in the household, the household status in the village, the age of the individual, etc. There are also many rules of etiquette for asking and doing favors.

Social order and rules

Mead describes the many group structures and dynamics in Samoan culture. Group formation is an important part of Samoan life from early childhood when young children form groups for games and pranks. There are different types of possible group structures in Samoan culture. Relationships proceed from chiefs and landlords; Men designate another man as their helper and representative in court rituals; Men form groups for fishing and other work activities; Women form groups that build on tasks such as childcare and household relationships. Mead describes examples of such groups and describes the complex rules by which they are formed and how they work. Her focus is on Samoan girls, but as elsewhere, she has to describe the Samoan social structures in their entirety to get a comprehensive picture.

Mead believes the complex and binding rules in these groups show that the traditional Western concept of friendship, as a bond voluntarily formed by two people with similar interests, is almost meaningless to Samoan girls: “Friendship is structured to be meaningless is. I once asked a young married woman if a neighbor with whom she constantly argued and disagreed was a friend of hers. ,Why? Of course, her father's father and my father's father were brothers. '"

The ritual requirements (e.g. remembering particularities with regard to family relationships and roles) are far greater for men than for women. This also means that men are given considerably more responsibility than women: "A man who commits adultery with the wife of a chief was beaten and exiled, sometimes even drowned by the angry community, but the woman was only thrown out by her husband" .

Mead devotes an entire chapter to Samoan music and the role of dancing and singing in Samoan culture. She regards them as significant because they violate the norms that define Samoans as good behavior in all other activities and offer Samoans a unique opportunity to express their individuality. According to Mead, there is usually no greater social failure than to demonstrate excessive pride or, as the Samoans describe it, "to pretend that you are older than you really are". However, this is not the case with singing and dancing. In these activities, individuality and creativity are the most valued qualities and children can express themselves to the full, instead of worrying about behavior appropriate to their age and status: The attitude of the elders to precociousness in ... singing or dancing is in stark contrast to their attitude towards any other form of required behavior. On the dance floor, the dreaded accusation “You act as if you were older” is never heard. Young boys who would be reprimanded or whipped for such behavior on another occasion are allowed to clean, flog, and babble and step into the limelight without a word of reproach. The relatives scream with joy about a precociousness for which they would hide their heads in shame if this were shown in another sphere ... Often a dancer does not pay enough attention to the other dancers not to collide with them all the time. It's a real orgy of aggressive individualistic behavior.

Character, sexuality and age

Mead describes the Samoan's mental state as simpler, more honest, and less determined by sexual neuroses than that of Westerners. She describes the Samoans as being much more casual about issues such as menstruation and more casual about non-monogamous sexual relationships. In their opinion, one reason for this is the extended family structure of the Samoan villages. Conflicts that can lead to disputes or disputes within a traditional Western family can be defused in Samoan families simply by causing one of the conflicting parties to move to another home that belongs to the village house.

Mead concludes the section of the book dealing with life in Samoa with a description of the Samoan age. Older Samoan women “tend to be more of a household power than the elderly. Men rule in part by the authority that their titles give them, but their wives and sisters rule by the power of their personalities and their knowledge of human nature. "

Upbringing Problems: Differences Between USA and Samoa

Mead concluded that the transition from childhood to adulthood is seamless, without the emotional or emotional distress, fear or confusion found in the United States.

Mead assumed this was because the Samoan girl was part of a stable, monocultural society, surrounded by role models, and that the fundamental facts of life such as intercourse, life and death, and the basic functions of life were not hidden. Samoan women are not under pressure to choose between conflicting values. She commented:

The father of a girl in the United States may be Presbyterian, vegetarian, teetotaler with a strong predilection for Edmund Burke, an advocate of union-free and high tariffs, who believes that women should be at the stove, that young women should wear corsets, not roll off their stockings, do not smoke or go out for a ride with young men in the evening. The mother, on the other hand, could be a member of the Lower Episcopal Church, for whom a high standard of living is important and who stands up for the rights of the state and the Monroe Doctrine, reads Rabelais, attends musical performances and horse races. Her aunt, on the other hand, is an agnostic, ardent defender of women's rights, an internationalist who believes in Esperanto, admires Bernhard Shaw and takes part in demonstrations against vivisection in her free time. Her older brother, whom she greatly admires, has just spent two years in Oxford, is an Anglican Catholic, full of enthusiasm for the world of the Middle Ages, writes mystical poetry, reads Chesterton and wants to devote his life to searching for the lost mystery of medieval stained glass . Her mother's younger brother ...

... [an American] girl's father may be a Presbyterian, an imperialist, a vegetarian, a teetotaller, with a strong literary preference for Edmund Burke , a believer in the open shop and a high tariff, who believes that women's place is in the home, that young girls should wear corsets, not roll their stockings, not smoke, nor go riding with young men in the evening. But her mother's father may be a Low Episcopalian, a believer in high living, a strong advocate of States' Rights and the Monroe Doctrine , who reads Rabelais , likes to go to musical shows and horse races. Her aunt is an agnostic, an ardent advocate of women's rights, an internationalist who rests all her hopes on Esperanto , is devoted to Bernard Shaw , and spends her spare time in campaigns of anti-vivisection. Her elder brother, whom she admires exceedingly, has just spent two years at Oxford . He is an Anglo-Catholic, an enthusiast concerning all things medieval, writes mystical poetry, reads Chesterton , and means to submissive his life to seeking for the lost secret of medieval stained glass. Her mother's younger brother.

Impact history

When it was first published, Mead's book received a great deal of attention from both academia and the general press. Her publisher William Morrow had compiled recommendations from well-known scholars, including Bronislaw Malinowski and John Watson . Her praise for Mead made the book successful and attracted public interest. This was followed by sensational headlines such as "Samoa is the Place for Women" and Samoa is the place "Where Neuroses Cease".

Consequences for ethnological research

Before Mead, in-depth immersive fieldwork had not been common practice. Even if errors were later proven in this area of empirical research, the idea of living together with the indigenous people was something fundamentally new. Their cultural comparisons for the purpose of analyzing Western societies were extremely influential and brought ethnological research into the focus of public interest in the United States. Mead remained the leading figure in ethnology for 50 years.

Reactions

As Boas and Mead expected, this book angered many readers in the Western world when it first appeared in 1928. Many American readers were shocked to see young Samoan women postponing marriage for many years, enjoying casual sex before finally choosing a husband. As a seminal study of sexual mores, the book has been highly controversial and has been frequently attacked on ideological grounds. For example, the National Catholic Register argued that Mead's findings were merely a projection of her own sexual beliefs and a desire to remove restrictions on her own sexuality. The Intercollegiate Studies Institute named Coming of Age in Samoa No. 1 on the list of the "50 Worst Books of the 20th Century".

Criticism of methodology and results

Although Coming of Age in Samoa received widespread interest and praise from the academic community, Mead's research methodology has also been criticized by several reviewers and anthropologists. Mead has been criticized for failing to distinguish her personal speculations and opinions from her ethnographic description of Samoan life and for making sweeping generalizations based on a relatively short period of study. For example, Nels Anderson wrote of the book, “As far as science is concerned, the book is a bit disappointing. The document base is missing. Too much is being interpreted and too little is being described. Dr. Mead too often forgets that she is an ethnologist, she mixes her own personality with her subject. ”Shortly after Mead's death, Derek Freeman published a book, Margaret Mead and Samoa, which claimed that Mead was not methodologically correct and that her claims were wrong without a factual basis. This criticism is discussed in detail in the following section.

The Mead-Freeman Controversy

In 1983, five years after Mead's death, Derek Freeman - a New Zealand anthropologist who lived in Samoa - published Margaret Mead and Samoa. The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth. He questioned all of Mead's key findings. In 1988 he took part in the filming of Margaret Mead in Samoa, which was directed by Frank Heimans. The film claims to document one of Mead's original informants, now an elderly woman, swearing that the information she and her friend Mead provided when they were teenagers was false; One of the girls said years later in a video, “We girls pinched each other and said we were out with the boys. We were just kidding, but she took it seriously. As you know, Samoan girls are great liars and love to make fun of people, but Margaret thought it was all true. ”Another statement from Mead that Freeman focused on was her claim that Samoan girls by the use of chicken blood could and would fake their virginity. Freeman pointed out that the virginity of the bride is so important to the status of Samoan men that they have a specific ritual in which the bride is manually deflowered by the groom himself or the chief, which makes it impossible to deceive with chicken blood. Because of this, Freeman argued that Mead must have relied on hearsay (false) from non-Samoan sources. "In 1943 I knew what the 'fa'amasei'au' rite meant, so I was certain that Mead's report was flawed and could not have come from a Samoan source."

The dispute related to the role of the Taupou system in Samoan society. According to Mead, the Taupou system is a system of institutionalized virginity for high-ranking young women, and it is reserved exclusively for high-ranking women. According to Freeman, all Samoan women mimicked the “Taupou” system and Mead's informants denied having casual sex as young women, claiming they lied to Mead.

Ethnological reception

After an initial flurry of discussion, many anthropologists concluded that Freeman was systematically misrepresenting Mead's views on the relationship between nature and care and the data on Samoan culture. According to Freeman's colleague Robin Fox, Freeman seemed to have reserved a special place in Hell for Margaret Mead "for reasons that were not clear at the time."

In addition, many field and comparative studies by anthropologists have found that adolescence is not experienced in the same way in all societies. Schlegel and Barry's systematic cross-cultural study of adolescence, for example, concluded that adolescents maintain harmonious relationships with their families in most non-industrialized societies around the world. They find that when family members need each other throughout their lives, independence, expressed in terms of youthful rebellion, is minimal and counterproductive. Teens are likely to be rebellious only in industrial societies that practice neo-local residency patterns (where young adults are forced to move away from their parents). Neo-local residence patterns are the result of the fact that young adults are moving to new places of work. Hence, Mead's analysis of conflict among adolescents is confirmed in the comparative literature on societies worldwide.

First, these critics expected him to wait for Mead to die before posting his review so she couldn't respond. In 1978, however, Freeman had already sent a revised manuscript to Mead. But she was already sick and died a few months later without answering him.

The second point of criticism was that the Witnesses had changed, they had grown old and converted to Christianity. The Samoan culture has also developed. This explains that their responses to Freeman were different from what they had given Mead many years earlier.

Freeman has also been attacked for methodological and empirical weaknesses in his work. He mixed public with private statements. He himself had discovered premarital intercourse (in a West Samoa village he recorded that 20% of 15-year-olds, 30% of 16-year-olds and 40% of 17-year-olds had had premarital sex) In 1983, the American Ethnological Association came to Freeman without an invitation on the resolution that his work was "poorly written, unscientific, irresponsible and misleading". Freeman rejected this bogus democratic condemnation as unscientific due to the majority of those present.

In the following years, Freeman's criticism continued to be fiercely disputed; GN Appell was convinced; Brady saw confirmation of the general concerns raised by Feinberg, Leacock, Levy, Marshall, Nardi, Patience, Paxman, Scheper-Hughes, Shankman, Young, and Juan.

Freeman was also accused of ideologically motivated one-sidedness ( sociobiology and interactionism), his statements on sexual morality were relativized by public statements because of their justification, while Mead had investigated actual practices.

Today's view

Psychology Today judged Mead's work to be pure fiction.

See also

- Culture of Samoa

- Heretic , a play by Australian playwright David Williamson that explores Freeman's reactions to Mead.

- The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia

Individual evidence

- ↑ Deborah G. Felder : A Century Of Women: . The Most Influential Events in Twentieth-Century Women's History . Citadel , 2003, ISBN 978-0-8065-2526-6 (English).

- ↑ Steven Pinker : How the Mind Works Reissue Edition . WW Norton & Company , 2009, ISBN 978-0-393-33477-7 (English).

- ^ A b c Paul Shankman : The Trashing of Margaret Mead: Anatomy of an Anthropological Controversy . University of Wisconsin Press , 2009, ISBN 978-0-299-23454-6 (English).

- ^ The Trashing of Margaret Mead . In: Savage Minds . October 13, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ A b c Margaret Mead : Coming of Age in Samoa . A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization . William Morrow Paperbacks , 2001, ISBN 978-0-688-05033-7 (English).

-

^ Derek Freeman: Margaret Mead and Samoa. The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth . Penguin, Harmondsworth 1983, ISBN 0-14-022555-2 .

German translation: love without aggression. Margaret Mead's legend of the peaceful nature of indigenous people . Kindler, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-463-00866-1 . - ↑ See Appell 1984, Brady 1991, Feinberg 1988, Leacock 1988, Levy 1984, Marshall 1993, Nardi 1984, Patience and Smith 1986, Paxman 1988, Scheper-Hughes 1984, Shankman 1996, and Young and Juan 1985.

- ^ Freeman, 1983: 238-240.

- ^ A b John Shaw: Derek Freeman, Who Challenged Margaret Mead on Samoa, Dies at 84 . In: The New York Times , August 5, 2001.

- ^ Freeman's Refutation of Mead's Coming of Age in Samoa .

- ↑ Appell 1984, Brady 1991, Feinberg 1988, Leacock 1988, Levy 1984, Marshall 1993, Nardi 1984, Patience and Smith 1986, Paxman 1988, Scheper-Hughes 1984, Shankman 1996, Young and Juan 1985, and Shankman 2009.

- ^ Margaret Mead and the Great Samoan Nurture Hoax. Retrieved May 23, 2019 (American English).