Kleptogamy

Kleptogamy (from ancient Greek κλέπτειν kléptein , German 'steal, cunningly steal' and ancient Greek γάμος gámos , German 'marriage, marriage' ) describes a copulation strategy through which male animals try to sneak a mating. Here parasitize the kleptogamen males services of other males, such as the efforts in courtship or parental care , which is why Kleptogamie as a form of Kleptoparasitism can be considered. The term is used as a generic term for very different behavior in different taxa . In addition, there is a large number of words that try to describe the behavior, but also the parasitic males.

Terms and Definitions

In English-language literature, “ kleptogamy ” and “ cuckoldry ” are often used synonymously. In a social sense, “ cuckoldry ” describes the situation in which a man of a cheating partner becomes a cuckold or a cuckold . The social understanding of the term " cuckoldry " led to discussions about the jargon in behavioral biology. In this sense, Patricia Adair Gowaty describes kleptogamy as a neutral technical term that is preferable to the English " cuckoldry " . By their definition, kleptogamy would be when one individual unwittingly reared the offspring of another. Harry W. Power notes that this definition does not distinguish kleptogamy from brood parasitism . He defines kleptogamy as the process when a male involuntarily raises the offspring of another male because the latter has mated the female of the former. Power also replies that Cuckoldry is more suitable. The term is less anthropomorphic because its roots are in Cuculus - a genus of the cuckoo family - whereas that of kleptogamy ( stealing , marrying ) is clearly in human behavior.

However, definitions have also been drawn up which regard kleptogamy as detached from brood care and which are very broad, for example those in the Dictionary of Science and Technology (first sentence in the introduction to this article). The term kleptogamy was also used with the red deer ( Cervus elaphus ) to denote the kidnapping of cows from a pack by young deer, especially when top dogs are engaged in comment fights .

Description and occurrence

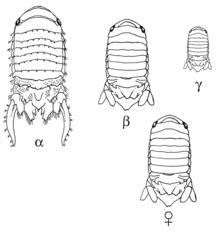

Kleptogamy occurs in many vertebrates and some invertebrates. It is usually practiced by weak males who cannot survive in direct competition or it develops because the effort-success ratio for kleptogamy is lower than for territorial behavior. The kleptogamous males can come from outside a group or develop within a group, for example in a pack or in a breeding colony. Several specialized morphs of males can also develop that pursue genetically determined strategies, for example three in the Paracerceis sculpta .

Kleptogamous males parasitize the courtship efforts of territorial males who must assert themselves against other territorial males in order to hold territory and gain a female. Territorial males are exposed to an increased risk of being captured, which kleptogamous males can avoid. In addition, territorial males can be parasitized during nest building and brood care. In addition, the territorial male incurs costs resulting from the competition for sperm . There can be a stable relationship between territorial males or males holding harem and kleptogamous males.

Kleptogamy in fish

Kleptogamy is widespread among fish. With them, kleptogamy is favored by external fertilization , during which the eggs are also accessible to the sperm of the kleptogamous male. First, the kleptogamous male observes a mating ritual, in which a female offers herself to a non-kleptogamous conspecific who can successfully claim a territory. At an opportune time during the spawning process, the kleptogamous male ejaculates its sperm near the spawning female. If the territorial male discovers the kleptogamous male, it will be driven away. Should the kleptogamous male succeed in ejaculating, part of the brood will descend from the kleptogamous male. Territorial males release a little less sperm than is necessary for the eggs to be fertilized. In this way they can serve a larger number of females and the male increases his reproductive success. In addition, they adapt the amount of ejaculation to the presence of (sighted) kleptogamous males: If only a few kleptogamous males are present, the territorial male increases the amount, but if there are too many kleptogamous males, the territorial male waives an increased amount by not to waste semen.

When kleptogamous males adopt the appearance and behavior of females in order to sneak up on a spawning female, they practice auto-mimicry , more precisely also called sexual mimicry or female mimicry. For example, the ability to change color can help the male to imitate females. Such males are also referred to as "sneakers" (Schleicher) or their behavior as "sneaking mating". In contrast, there are kleptogamous males who jump out of a hiding place, surprise a spawning couple and ejaculate next to them; their tactics are also known as satellite tactics. Kleptogamous fish can be pursued or killed, or the spawning business can be interrupted by the female if it detects a kleptogamous male.

The choice of tactics by the individual or the frequency of tactics in a population is primarily dependent on the female / male or strong-male / weak-male ratio. In addition, the pressure of predation also has an effect , since kleptogamy carries fewer risks against predators than intra-species fighting for territories. The fertilization rates of kleptogamous males vary from species to species and from population to population. In the case of the Atlantic salmon ( Salmo salar ), for example, a fertilization rate of 5% has been proven experimentally.

Kleptogamy in birds

In birds, kleptogamy manifests itself primarily in the promiscuous behavior of the females. Breeding colonies and larger population densities increase the risk of kleptogamy. In order to counteract kleptogamy, a male bird can guard the fertilized female during its prolonged fertile phase (pair guarding), attack and scare away foreign males and thus prevent fertilization of other males. In glans Spechten ( Melanerpes formicivorus ) occurs during the breeding participation by hatching helper for active control of the main female male through the main to prevent Kleptogamie. Alternatively, male birds with regular copulations can increase the likelihood that the eggs will be fertilized by them. Copulations are repeated between one and 500 times, depending on the species. Counter-strategies are increasingly found in species whose males carry out extensive brood care and want to ensure that the offspring come from them. This behavior ends with the fertile phase of the female, often before the offspring hatch.

Because of kleptogamy, it is usually difficult to ascertain whether all offspring come from the same male.

Individual evidence

If there are individual references to a word, only reference this. If the individual references come after a point, they reference the preceding sentence, several sentences or an entire section, provided they are not interrupted by other references at the end of a sentence.

- ^ Wilhelm Pape , Max Sengebusch (arrangement): Concise dictionary of the Greek language . 3rd edition, 6th impression. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig 1914 ( zeno.org [accessed on December 5, 2019] The word does not exist in ancient Greek in this form; ancient Greek κλεψιγαμία klepsigamía , German 'Buhlerei [in the sense of adultery or enjoyment of stealthy love ]' comes from the meaning the next.).

- ^ Wilhelm Pape , Max Sengebusch (arrangement): Concise dictionary of the Greek language . 3rd edition, 6th impression. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig 1914 ( zeno.org [accessed December 5, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Dictionary of Science and Technology . Academic Press, Inc., 1992, ISBN 0-12-200400-0 , pp. 1185; Keyword "kleptogamy" ( limited preview in google book search). Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Nishimura, K .: Kleptoparasitism and Cannibalism (English; PDF; 319 kB). Hokkaido University, Hakodate, Japan, 2010 Elsevier Ltd. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ↑ Cynthia Chris: Watching wildlife . University of Minnesota Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8166-4546-6 , pp. 149 ( limited preview in Google Book search). Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- ↑ Jimmie Killingworth, Jacqueline Palmer: Ecospeak . Souther Illinois University, 1992, ISBN 0-8093-1750-8 , pp. 115 ( limited preview in Google Book search). Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- ↑ Gowaty, PA: Sexual Terms in Socio-Biology: Emotionally, Evocative, and Paradoxically Jargon . Animal Behavior 1982, 30. pp. 630-631.

- ↑ Patricia Adair Gowaty: Cuckoldry: The limited scientific usefulness of a colloquial term . Animal Behavior, Volume 32, Issue 3, August 1984, Pages 924-925. doi: 10.1016 / S0003-3472 (84) 80175-X

- ↑ a b Power, Harry W. Why "kleptogamy" is not a substitute for "cuckoldry." in Animal Behavior , Vol 32 (3), Aug 1984, 923-924. doi: 10.1016 / S0003-3472 (84) 80174-8

- ^ Power, Harry W. Why "kleptogamy" is not a substitute for "cuckoldry." in Animal Behavior , Vol 32 (3), Aug 1984, 923-924. doi: 10.1016 / S0003-3472 (84) 80174-8 Power refers to: Clutton-Brock et al. (1979): The logical stag: adaptive aspects of fighting in red deer ( Cervus elaphus L.).

- ^ Klaus Immelmann: Dictionnaire de l'éthologie . Verlag Paul Parey, 1990, ISBN 2-87009-388-8 , pp. 53 ( limited preview in Google Book search - keyword "Cleptogamie, Kleptogamie, Cleptogamy, sneaking mating" ). Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d Michael Taborsky: Sneakers, Satellites, and Helpers: Parasitic and Cooperative Behavior in Fish Reproduction (English; PDF; 4.2 MB). Advances in the Study of Behavior, VOL. 23, 1994.

- ↑ a b c Technical terms were translated with the help of: Manfred Eichhorn et al .: Langenscheidt specialist dictionary biology English: English-German, German-English . Cambridge University Press, 1981, ISBN 0-521-23316-X ( limited preview in Google Book Search). "cleptobiosis" / "Kleptobiosie, Lestobiose" p. 164; "cuckoldry" / "Brood Parasitism" p. 196; "kleptogamy" / "kleptogamy" p. 399; "kleptoparasitism" / see "cleptobiosis" p. 399; "mate guarding" / "Paarbewachung" p. 436; "sneaky mating" / see "kleptogamy" p. 616; "Sperm competition" / "Sperm competition" p. 624. Retrieved on February 26, 2011.

- ↑ Dennen, van der, J .: The origin of war: the evolution of a male-coalitional reproductive strategy . Origin Press, 1995. p. 42.

- ↑ a b Stéphan Reebs: The sex lives of fishes (English; PDF; 107 kB). Université de Moncton, Canada 2008. p. 2.

-

↑ Tim Birkhead: Promiscuity . Faber and Faber, London 2000, ISBN 0-571-19360-9 . P. 128.

Tim Birkhead refers to: Petersen et al. (1992): Variable pelagic fertilization success: implications for mate choice and spatial patterns of mating ; and: Warner et al. (1995): Sexual conflict: males with highest mating success convey the lowest fertilization benefits to females . -

↑ Tim Birkhead: Promiscuity . Faber and Faber, London 2000, ISBN 0-571-19360-9 . Pp. 128, 129.

Tim Birkhead refers to: Petersen and Warner (1996): Sperm Competition in fishes ; in Birkhead and Møller (1998): Sperm Competition and Sexual Selection ; and: Parker: Sperm competition games: raffles and roles (1990) and Sperm competition games: sneaks and extra-pair copulations (1990). - ^ A b Klaus Lunau : Warning, camouflaging, deceiving . Completely revised new edition 2011 of the 1st edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt, ISBN 978-3-534-23212-3 . Pp. 90-93.

- ^ Klaus Lunau : Warning, camouflaging, deceiving . Completely revised new edition 2011 of the 1st edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt, ISBN 978-3-534-23212-3 . P. 93.

- ^ Robert R. Lauth et al .: Behavioral Ecology of Color Patterns in Atka Mackerel , (English). Marine and Coastal Fisheries: Dynamics, Management, and Ecosystem Science 2: 399-411. 2010.

- ↑ Mart R. Gross: Alternative reproductive strategies and tactics: diversity within sexes (English; PDF; 1.2 MB). Elsevier Science Ltd, 1996. p. 96

- ↑ Zoltán Barta, Luc-Alain Giraldeau: Breeding colonies as information centers: a reappraisal of information-basad hypotheses using the producer-scrounger game (PDF; 155 kB), (English). Behavioral Ecology Vol 12. No. 2: 121-127.

- ↑ Mumme, RL et al .: Mate Guarding in the Acorn Woodpecker ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English; PDF; 1.3 MB). Anim. Behav. 1983, 31, 1094-1106

- ↑ Tim Birkhead: Promiscuity . Faber and Faber, London 2000, ISBN 0-571-19360-9 . P. 55.

- ↑ Hiatt, LR: On Cuckoldry . Journal of Social and Biological Systems. Volume 12, Issue January 1, 1989, pages 53-72. doi: 10.1016 / 0140-1750 (89) 90020-1

- ↑ Bendall, DS: Evolution from molecules to men . Cambridge University Press, 1983, ISBN 0-521-24753-5 , pp. 463 ( limited preview in Google Book search). Retrieved May 17, 2011.